“Whatever you do you need courage. Whatever course you decide upon, there is always someone to tell you that you are wrong. There are always difficulties arising that tempt you to believe your critics are right. To map out a course of action and follow it to an end requires the same courage that a soldier needs. Peace has its victories, but it takes brave men and women to win them.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Daddy, Daddy, we missed you,” screamed my oldest daughter Suzy, running and jumping on me as soon as I closed my car door.

Jennie, three, although less animated than Suzy, hugged her father, too. Debbie just cried.

I had just spent 10 days in the jungle. We played war games, getting attacked by the Opposing Forces (OPFOR), “guerillas” from the fictional Latin American country of Rio Bravo. I would never have admitted this to my wife, but I enjoyed the field: sleeping on a cot, trading shots with bad guys played by Green Beret soldiers, the best the Army had to offer, even, picking up stakes – day or night -and moving our unit three or four times during the training.

Despite all the training and hard work, life in Panama was idyllic for the American soldiers of the 193rd Infantry Brigade and their families in the late 1970s. A contentious and unpopular war in Southeast Asia ended a few years earlier, and the isthmus was a great place to recover from any psychic or physical trauma it caused. Unlike Vietnam, Panama had peaceful pristine beaches where we didn’t need to be armed to enjoy an hour of fun in the sun. Panama was the home of tranquil sports like fishing, a pastime that relieved the tension and stress of war. The notion of an assignment with family members in country accompanying the soldier was far better than the depressive isolation caused by an solo assignment in a combat zone.

The Canal Zone, 55 miles long, intersected the Isthmus of Panama at its narrowest points. Called the “Big Ditch” from the time its construction began in 1904 until it was completed 10 years later, this wonder of the world was bounded by lush green jungle most of the year, but from mid-November to February, the short dry season, the jungle turned brown and often caught fire.

Situated between Costa Rica, Central America’s oldest democracy, to its northwest and Columbia to its southeast, Panama was bounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the northeast and the Pacific Ocean to its southwest. The land changes from tall and majestic volcanic mountains as you travel from Costa Rica to Panama’s capital, Panama City on the Pacific side of the canal, to the thick, nearly impenetrable jungle of the Darien if you headed toward Columbia.

It was not unusual during the periods of fire in the jungle near our house, to wake up, step outside and discover all sorts of incompatible fauna lying on the lawn in exhaustion after fleeing the flames in the jungle. Various snakes, coatimundi, three-toed sloths, white-faced capuchins, iguanas and other indigenous beasts rested in the grass, still green and moist from its nightly watering.

Among old Canal Zone hands, Panama was known as the best kept secret in the Army. Military duty was the same the world over, but the environment in which a soldier works and plays makes all the difference. The temperature was always balmy. In November 1978, the long rainy season was waning and Canal Zone residents were eagerly waiting Thanksgiving and Christmas. The two holidays were also anticipated because they signaled the commencement of the short, but enjoyable dry season.

Field duty in Panama was always an adventure. The jungle was full of dangers to man and pet, from the fer de lance, coral and bushmaster snakes that kill several Panamanians a year to urticating caterpillars, scorpions and poisonous toads that can be detrimental to the curious dog. It teemed with other animals like toucans, howler monkeys, green iguana, and spider monkeys that could only be viewed in zoos at home. The Poinsettia plant, so familiar at Christmas in North America, grew tall as a tree in Panama. Mango trees and banana plants were as plentiful as apple trees in Oregon and the exotic black palm tree protected its sweet fruit with two inch long spines in its trunk.

Many soldiers took time during field exercises to participate in hobbies, some of which were pastimes that could be performed in very few duty stations around the world. Photography was popular and shooting the creatures that lived in the jungle, like the large variety of parrots, the rarely seen tapir and the elusive jaguar, with a long lens on a 35 mm camera may have been a common hobby but the subjects were most uncommon to us.

I collected the fragile and rare orchids that grew high in the trees of the rain forest. No, I didn’t climb these trees, I would look for one that had fallen and carefully harvest the flowers.

When I left Panama in 1980, my patio looked like an orchid shop. My favorite was the ada orchid, with its spidery-like yellow orange flowers and exotic fragrance. I also had the rare brassia and some clowesia. All in all, I left more than two dozen specimens on my patio for the next occupants to enjoy.

My wife collected the butterflies that either were indigenous to Panama or migrated through every year. Big blue morphos, the diminutive eurema daira, the orange/black Erato Heliconian, and the blue/black two barred flasher were just four of the hundreds of species Mai captured. She would carefully dry and preserve them, then mount them in a glass frame.

When the weekend arrived, there were a variety of recreational activities for soldiers and their families to participate in. The Army ran boat rental facilities on Gatun Lake, a body of water formed by the Madden Dam to create the waterway that ships travel through to get from the canal locks on the Atlantic side to the locks on the Pacific end of the canal. It was a rare weekend when there were boats left to rent by those who enjoyed fishing for the plentiful, pretty and delicious peacock bass.

Others would seek out smaller species of fish, the beautiful tropicals that inhabited the streams and lagoons of Panama. I kept three aquariums, all with fish obtained in the wild: convict and pastel cichlids, banded tetra, spotted hatchet fish, and a live bearer known as the merry widow were among my collection.

The Pacific Ocean provided incredibly intricate and fragile shells. Several members of the 601st Medical Company and their families were hooked on collecting live specimens. During extremely low tides, called minus tides, that usually occurred at night, shellers would walk out to places normally covered by many feet of water and gather up specimens seldom seen closer to shore. Once caught, the meat was carefully picked out and the shell was cleaned and coated with oil. Some of these shells were very valuable.

The beaches were plentiful and majestic. Americans could be found in droves on both the Atlantic and Pacific sides of the isthmus, enjoying the surfing that some were famous for, seeking lobster in the rocky reefs near some of the beaches, or just tanning in the sun or swimming in the sea.

Not only was Panama known for its abundant free time activities, the living quarters, for the most part, were superior to Army housing in other parts of the world. They were spacious. Most were air conditioned, and the yards in the housing areas were like gardens with Majesty Palms lining the streets.

Often between houses, one would find huge, colorful poinsettias and bougainvilleas or smaller palm trees like the spacious areca. Elephant ears were common plants along the houses. Intermingled with flowering bromeliads in the beds and another species of bromeliad, the staghorn fern, in the trees.

Our neighborhood, Corozal, was next to Albrook Air Force Base and just south of Fort Clayton. Centrally located on the west bank of the Canal Zone, Corozal was very convenient to schools, shopping and the shuttle bus that would take family members without transportation anywhere they needed to go. The commissary where we purchased most of our groceries was just down the hill, making it easy for my wife to shop, since she didn’t have a driver’s license. The edge of the jungle came up to my yard, allowing my three daughters to watch the animals that would come out of the wild in the evening to feed on the mango tree in our yard.

Kinkajous, small primates that resemble teddy bears, dined in our tree every night. Coatimundi, cousins to the American raccoon, would brazenly approach children eating snacks and brazenly take the food from them if they refused to share their treats.

The youngsters of the neighborhood shared the mango tree’s bounty with these animals. Exotic tropical fruits also were eaten with delight when soldier-parents brought them home from the jungle or when they were purchased in the local market. Other foods were plentiful and reasonably priced, especially for the more daring who shopped in Panama’s Central Market. Although they were not inspected as well as meats in America and were not maintained in wrapped packages in refrigerated displays, steaks could be had for about 38 cents a pound. Fish was even less expensive and more abundant.

My three girls, thrived during the years they lived in the Canal Zone. After having wintered at Fort Dix, New Jersey, before joining me, they appreciated the freedom of being able to go outside and play without having to bundle up in several layers of clothing. The children, who often experienced colds, sore throats and earaches when we lived in the United States, In Panama they were virtually illness-free during our four year tour. The country literally seemed like an elixir for them.

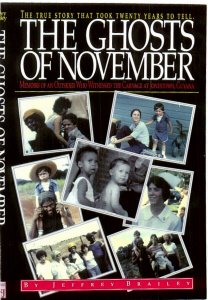

Life in Panama that November was good. On the 18th, it was particularly good. My daughters were ages 7, 3 and 2. Their names, respectively, were Suzanne, Jennifer and Deborah. I didn’t know it at the time, but that day was going to be the most significant one in my life.

It took me five years and several sessions with an Army psychologist to get the events of that day out of my mind. They would return to literally haunt my dreams around Thanksgiving and stay with me for two weeks or so.

In the meantime, I became obsessed with the evil side of religion. The world is full of religious cults, some of them healthy, the vast majority that are benign and some that are very dangerous. The identification and study of this last group of cults became a daily activity for me. I joined the appropriate organizations and subscribed to the pertinent magazines. I was an active member of the Cult Awareness Network until it was infiltrated and taken over by adherents to an organization that, while admittedly is a cult, I believe fits into the benign category.

Who would believe a day in the life of a complete stranger, whom I never met or even heard of, would have such a profound affect on me? A man mind you, who was almost 1500 miles from me and who was spending his final day on earth; a man who was having probably the worst day of his life, while mine was looking bright and sunny. It was Saturday and my family and I were going to the beach.

While I was packing my family into the car for the short ride to Kobe Beach, a man in black three countries away was trying to keep what he considered his family from falling apart. We sang children’s songs as we made our way to the beach in the black 1965 Peugot 504 I purchased for $500 four months earlier at the lot in the Canal Zone the government allowed us to buy, sell and trade. Thanksgiving was a week away, the turkey was in the freezer and all the fixings were in the pantry and refrigerator.

The man in black had been trying for two days to show his family in its best light. Persecuted and misunderstood, he was quickly reaching the end of his rope as he listened to the visitor he reluctantly allowed to enter his home, knowing full well it was his downfall the ominous visitor sought.

Arriving at the clean white sandy beach at Fort Kobe, the girls rushed to play with their friends while their mother and I brought the beverages and foods to the picnic table already staked out by one of her friends. High fives and greetings all around were the first order of the day, as about a dozen other soldiers who were married to Vietnamese war brides greeted me. The only time we all got together was these almost bimonthly outings. Other than that, we were each in different units on different posts, some as far as Fort Sherman, on the Atlantic Side.

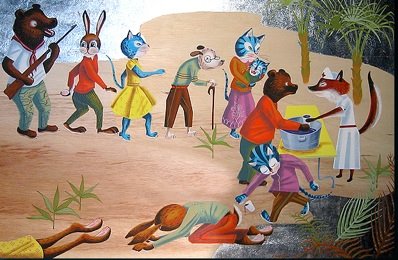

At about the time we were gathering together, the man in black was calling his people to a meeting. Minutes before, less than 20 of his brothers and sisters and some of their children had been taken out of the family compound by the visitor from the United States government. There was a crisis in the family, one the man in black was certain would doom it forever.

Meanwhile, at the beach, the delicious aroma of various ethnic dishes intermingled with the smell of barbecue that Command Sergeant Major Sargent was sweating over. The children were playing volleyball and getting wet at the ocean’s edge, under the watchful eyes of several lifeguards. The adults were getting set to play cards, Spades for the men and Bai Tu Sac for the women.

Where the man in black was, the odor was one of fear and no one was playing. Crowded into the communal pavilion, the family members weren’t hungry, they were scared. There was a drink being prepared for every member of the family, one that some would partake of voluntarily, others with final relief, but most with reluctance and trepidation, spurred on by men with guns. You see, there was no playing with the man in black. This was a bizarre last communion that would soon mark the end of this very large family.

Of course, you realize the man in black and the awful creator of my horrendous annual November nightmares was Jim Jones and his family was called the People’s Temple. On that November 18 in 1978, while my family enjoyed the bounty and beauty of the tropics, Jones’ family finally attained peace, a peace that was long in coming, but a peace nonetheless.

My children and their friends anxiously anticipated the Thanksgiving holiday which was only a few days away. The poinsettia tree that towered over the side wall of our house was bursting with beautiful red blooms and the pleasant dry season was just beginning. Everyone’s spirit was merry.

This was my family’s third November in Panama and this pre-Thanksgiving outing to Kobe Beach had become a minor tradition to the families with American dads and Vietnamese moms. While our children played volleyball or swam, their parents sat at picnic tables playing cards.

The wives played a Vietnamese game that had red, blue, yellow and green cards with Chinese symbols on them. Bai Tu Sac, or Chinese Checkers, was a Vietnamese card game played with 112 little cards with orange backs. Often played whenever Vietnamese Army wives got together, the game was a social activity for most but an obsession for many, who played marathon games on a weekly basis. The husbands played the perennial favorite of all soldiers in the field, Spades.

Some of the more politically-minded of the dads were engaged in animated discussions about the “Panama Canal Giveaway” that was in the news. The expatriates who had come to “The Zone” to make a new life were furious at President Carter for threatening their way of life by proposing to turn the Canal Zone over to the Panamanians.

The issue didn’t matter much to me and my military friends. As soldiers and the family members who follow them on assignments around the world, this was just one more duty station in a career of new places to get used to.

While life in Panama was as good as it gets, and even though the duty was more desirable than in most other places, it wasn’t all fun and games. A soldier’s mission in peace time is to prepare for war, and that takes a lot of hard work.

As the medical unit that supported virtually every American infantry unit and school in the Canal Zone, the 601st Medical Company spent much of its time in the field and away from their families. If the unit’s field hospital was not actually set up providing emergency medical treatment to the sick and injured, its field ambulances were providing medical evacuation support.

By 1978, we were part of an all-volunteer force and the Army was becoming more soldier-oriented. It was an army that cared about the health, welfare and comfort of the troops and their families. This concern for those of us residing in the Canal Zone and serving our country was in sharp contrast to the lives of some of the 1000 or so other American citizens who had journeyed to an alleged tropical paradise beginning in December 1973.

[1] Jonestown was approximately 1450 miles

[2] from Panama, but it may as well have been a million light years away.

James Warren Jones, who became known as the Reverend Jim Jones, was born in Lynn, Indiana on May 13, 1931.

[3] In the 1950s and 60s in Indianapolis, Jones gained a reputation as a charismatic preacher and clergyman.

[4] By 1963, he had his own religious congregation, The People’s Temple Full Gospel Church. This incredibly dynamic orator, led his interracial congregation with amazing feats of faith healing

[5], awesome visions and miraculous advice he said came from extraterrestrials.

Jones moved his congregation from Indianapolis to rural Ukiah, California, in the early 1960s after reading that this region of the United States would be relatively safe from nuclear attack.

[6] He was convinced that Indianapolis would be a major target of the Soviets when the inevitable nuclear war between the USA and USSR occurred. He convinced most of his simple parishioners to share his fear.

Indianapolis was home to Fort Benjamin Harrison at the time. The Army post trained journalists, photographers and finance specialists. Although now closed, the US Army’s Finance Center is still located there.

The move to Ukiah, where Jones formed the People’s Temple, soon was followed by another move, this time to San Francisco.

[7] He became a major social and political force, establishing a free clinic and drug rehabilitation program. Jones was appointed chairman of the San Francisco Housing Authority in 1976.

[8]

Rev. Jones was the darling of liberal politicians. He attended functions for and supported Democratic Party candidates from the local level all the way to presidential candidate Jimmy Carter. He had his photo taken with Rosalyn Carter on at least one occasion.

[9]

But soon Jones was being attacked by former members of his church.

[10] The charges could not be ignored and his political cronies and connections could not support the besieged cult leader. He was accused of child abuse, misappropriation of the property of some church members and even the stealing of the children of some members.

[11]

Deborah Layton Blakely, a former Jones confidant, in an affidavit to the US Justice Department taken on June 15, 1978, reported the reaction he had to these accusations. Blakely belonged to the People’s Temple from August 1971 until May 13, 1978. She was financial secretary of the church until she went to Guyana in December 1977.

[12]

“During the years I was a member of the People’s Temple, I watched the organization depart with increasing frequency from its professional dedication for social change and participatory democracy. The Rev. Jim Jones gradually assumed a tyrannical hold over the lives of temple members,” wrote Blakely.

[13]

Jones regarded any disagreement with his dictates to be “treason.” According to Blakely, he labeled any person who left the church a “traitor” and “fair game.” He is said to have maintained that punishment for defection from the organization was death. Severe corporal punishment was frequently meted out to temple members, giving the death threats a frightening air of reality.

[14]

Jim Jones began seeing himself as the victim of a conspiracy. His identity of the conspiracy would change frequently, depending upon whatever vision of the world he had on a particular day. He told members of his congregation that because he was their leader and he was a victim of a conspiracy, they too were targets.

He told black temple members that if they did not follow him to Guyana, they would be put in concentration camps and killed. According to Blakely, “White temple members were instilled with the belief that their names appeared on a secret list of enemies of the state that was kept by the CIA. They believed they would be tracked down, tortured, imprisoned and subsequently killed if they did not flee to Guyana.”

[15]

By 1978, more than 1000 Americans who believed strongly in Jim Jones had left their homeland and journeyed to the supposed sanctuary of Jonestown. People who hear of this emigration for the first time wonder how apparently normal and intelligent adults could be taken in by such delusional thinking.

Jones was a master of deception and control. At temple meetings, he would talk nonstop for hours, his charismatic and forceful voice carried over a loud speaker system in the auditorium of the church building. His lieutenants would walk through the room waking up any members of the congregation who dared fall asleep during these marathon orations.

[16]

The egomaniacal Jones claimed to be the reincarnation of Moses, Lenin and even Jesus. He claimed he had divine powers and could heal the sick, that he had extrasensory perception and could tell what people were thinking. Jones even made the outrageous claim that he had powerful connections all over the world with the likes of the Mafia, the Soviet government and Idi Amin.

[17]

The Blakely affidavit states, “When I first joined the temple, Reverend Jones seemed to make clear distinctions between fantasy and reality. I believed that most of the time when he said irrational things, he was aware that they were irrational, but they served as a tool of his leadership. His theory was that the end justifies the means. At other times he appeared to be deluded by a paranoid vision of the world. He would not sleep for days at a time and talk compulsively about conspiracies against him. However, as time went on, he appeared to be genuinely irrational.”

[18]

Life for the transplanted Americans living in Jonestown, 1450 miles from where I lived and worked in Panama, was very different from that which my family and I enjoyed. The vast majority of Jonestown residents worked in the fields from 7 AM to 6 PM, six days a week and on Sunday from 7 AM to 2 PM.

Blakely reported, “We were allowed one hour for lunch. Most of this hour was spent walking back to lunch and standing in line for our food. Taking any other breaks during the workday was severely frowned upon.”

[19]

While food in Panama was plentiful and inexpensive, in Jonestown, meals were extremely basic and not very nutritious for most residents. According to Blakely’s affidavit, “The food was woefully inadequate. There was rice for breakfast, rice water soup for lunch and rice and beans for dinner. On Sunday, we each received an egg and a cookie. Two or three times a week we had vegetables. Some very weak and elderly members would receive one egg per day.”

[20]

Jim Jones enjoyed a much better diet than the members of his flock. Claiming he had problems with his blood sugar, he dined separately and ate meat regularly. Jones had his own refrigerator, well stocked with food.

The two women who lived with Jones, Maria Katsaris and Carolyn Layton and the two small boys who shared his quarters with him, Kimo Prokes and John Stoen, dined with other members of the cult. Blakely does report that these four individuals were in better health than the other residents because they were allowed to eat from Jones’ refrigerator.

“In February 1978, conditions had become so bad that half of Jonestown was ill with severe diarrhea and high fevers. I was seriously ill for two weeks. Like most of the other sick people, I was not given any nourishing food to help recover. I was given water and tea to drink until I was well enough to return to the basic rice and bean diet,”

[21] reported Blakely.

Blakely also stated in her affidavit, that as financial secretary, she knew the temple received over $65,000 in Social Security checks each month. “It made me angry that only a fraction of the income of the senior citizens in the care of the temple was being used for their benefit,”

[22] she wrote.

Jonestown had a very sophisticated state-of-the-art loudspeaker system that Jones used for up to six hours a day to broadcast his thoughts, threats and orders to every corner of the commune.

[23] When he was particularly agitated, he would rant and rave for longer periods without stopping. He could be heard in some of the oppressively hot fields where the residents of Jonestown toiled during the day. At night, his loud voice would prevent his tired congregation from sleeping. Often after work, there were also meetings at the pavilion that lasted up to six hours. Jones seemed to be infatuated with his own voice and prophetic message.

Jones’ paranoia caused his daily harangues and nightly meetings to be frightening affairs indeed. He was obsessed that his place in history had been irreparably ruined by the media. He felt their ridicule had caused him to lose an honored position in world affairs. He often complained that he was lost.

[24]

Blakely reported, “There was constant talk of death. In the early days of the People’s Temple, general rhetoric about dying for principles was sometimes heard. In Jonestown, the concept of mass suicide for socialism arose. Because our lives were so wretched anyway and because we were so afraid to contradict Reverend Jones, the concept was not challenged.”

[25]

Mike Prokes, a dissatisfied follower of Jones and one of his enforcers, kept a diary. He was a survivor of the mass suicide/murder. Prokes notes were part of a collection of records that were sealed after the massacre at Jonestown. The contents of the records were opened in September 1988.

“I don’t know how much longer I can take it,” wrote Prokes. “I mean the witchcraft. I feel like I am being programmed. I enjoy the violence when I do it, but sometimes, like right now, I feel sorry that I did it.”

“I think I am going to end it all with my .38; I only wish I could see my brains blow out.”

[26]

Ironically, Mike Prokes died a few months after the Jonestown Massacre. During a news conference, he pulled out his .38 and shot himself in the head.

[27]

Jones would declare a “White Night” or state of emergency as often as once a week. This was ushered in by the blaring of the loudspeaker system that would awaken the entire population of Jonestown. Jones’ trusted lieutenants would move from cottage to cottage and make sure everyone was responding. All the residents would gather in the pavilion for a mass meeting where they would be informed by Jones of some new crisis.

[28]

In her affidavit of June 15,1978, almost five months prior to the mass suicide/murders, Blakely wrote, “During one ‘white night,’ we were informed that our situation had become hopeless and that the only course of action open to us was a mass suicide for the glory of socialism. We were told that we would be tortured by mercenaries if we were taken alive. Everyone, including the children, was (sic) told to line up. As we passed through the line, we were given a small glass of red liquid to drink. We were told that the liquid contained poison and that we would die within 45 minutes.

“We all did as we were told. When the time came when we should have dropped dead, Reverend Jones explained that the poison was not real and that we had just been through a loyalty test. He warned us that the time was not far off when it would become necessary for us to die by our own hands. Life in Jonestown was so miserable and the physical pain of exhaustion was so great that this event was not traumatic for me. I had become indifferent as to whether I lived or died.

“We would be told that the jungle was swarming with mercenaries and that death could be expected any minute,” reported Blakely.

These “White Nights” were bizarre rehearsals for the real moment when Jones would have his doctor and nurses dispense a potion of cyanide combined with strong anticonvulsants, sedatives, hypnotics, tranquilizers, and muscle relaxants mixed, not with grape Kool-Ade from the United States as popularly reported, but with Flav-Or-Ade, a powdered drink mix manufactured in the United Kingdom.

Two very different groups of Americans were living in the tropics that November. Less than 1500 miles from each other, one group lived in a place called the best kept secret in the US Army. The second group of nearly 1000 was living in a better kept secret, Jonestown, Guyana. One group was enjoying life in a tropical paradise, the other group living lives that could only be described as hell on earth.

Events that occurred on the 18th of November 1978, would inexorably connect members of these two groups. As traumatic as what occurred in Jonestown was to its American expatriate residents, the trauma ended that evening for most of them. For those of us who were ordered to report to Guyana from military posts around the western hemisphere, the trauma was yet to begin.

[1] Ethan Feinsod, ibid, 100; FOIA Federal Bureau of Investigation RYMUR (Jonestown), 151-152

[2] Bali and Indonesia on the Net, How Far is IT?. Retrieved June 23, 2004 from http://www.indo.com/distance.

[3] David Chidester, Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, The People’s Temple and Jonestown, (Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press, 2003, I.

[4] John Peer Nugent, Ibid, 10-19.

[5] John R. Hall, Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History, (New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction Publishers, 2001) 41-45.

[6] FOIA Federal Bureau of Investigation RYMUR (Jonestown), ibid, 50; David Chidester, ibid, 6.

[7] John R. Hall, Ibid, 69.

[8] Ibid, 169-170

[9] Ibid, 168; Jonestown Audiotape Primary Project: Transcripts, Tape Number Q799, Tape Number Q622; Deboral Layton, Seductive Poison, (New York, Doubleday, 1998) 65.

[10] Jeannie Mills, Six Years with God, (New York, A&W Publishers, Inc, 1979)

[11] Jeannie Mills, Ibid.

[12] Deborah Layton, Ibid.

[13] Deborah Layton Blakely, Affidavit of Deborah Layton Blakely Re the Threat and Possibilities of Mass Suicide by Members of the People’s Temple, June 15, 1978. This affidavit was written within four weeks after Deborah Layton’s escape from Jonestown and became front page news across the country. Six months later and just four days before the tragedy, Deborah was giving testimony before State Department officials, requesting help for the 900 held against their will in Jonestown, Guyana.

[14] ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid

[17] Ibid

[18] Ibid

[19] Ibid

[20] Ibid

[21] Ibid

[22] Ibid

[23] Ethan Feinsod, ibid, 188; Deborah Layton, ibid, 178.

[24] Deborah Layton Blakely, ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] U.P.I., Jonestown ‘diary of the dead’ resurfaces, September 18, 1988.

[27] Ibid

[28] Deborah Layton Blakely, Ibid.

No comments:

Post a Comment