The work of art known as Jonestown Carpet has been described by critics both as a “work of prolonged commitment” and a “maniacally obsessive, fascinating and hopeless act of purification.” As the artist responsible for Jonestown Carpet, I am not sure which of these descriptions I prefer. As I understand it, my job as an artist is to deal in appearances and to encourage perception. My practice centers on those aspects of being that I find most compelling. Through the course of my career, my choices in subject matter have reflected an abiding interest in sex and death. Some of those subjects seem to call for more complex or arduous treatments than do some others.

Reviews of Jonestown Carpet often include the information that the project took ten years to finish (1981 to 1991). In fact it took ten years to create the tapestry rug that is the central feature in this work, though Jonestown Carpet is not and will never be a finished work. To attest to this incompleteness, a minor area of the carpet canvas was left without needlework; essentially, a blank space.

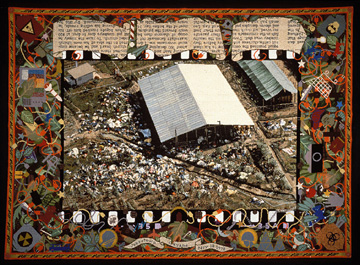

The subject I chose in 1981 was not the Jonestown tragedy per se, but rather, an aerial photograph of the Jonestown dead by David Hume Kennerly for Time Magazine. The first photos of Jonestown to emerge in the news media were similar – and, to readers of this report, familiar – images: wide, aerial views of the carnage scattered over the landscape. For many people, the most striking thing about these photographs was that they did not appear to match up with the captions or the news story.

In an Art News Magazine article, Marvin Heiferman, a curator of photography, spoke about Frank Johnston’s photograph of that same aerial view: “It didn’t show you the whole picture. It wasn’t narrative enough. The subject wasn’t clear, not in terms of focus or anything… It was presented as a document, [but] there were no clues.” Heiferman went on to say that photograph left him ” more conscious of the way pictures relay information to you and the way pictures manipulate information and either reveal things or hide things.”

The first time I saw an image of the Jonestown dead, it was a hazy black and white photograph on the front page of The Globe and Mail, a Toronto newspaper. I remember the impatient feeling of wanting that picture to show me something more than the slopes of a few rooftops – something that might be recognized as death – but that something simply could not be discerned, even with the help of a magnifying glass. There was no way I could see what I was looking for in the picture I was looking at.

Eventually I resolved that it was my task to attempt to discover the something of what had been lost in those wide, aerial pictures of the Jonestown dead. In an oblique way, the sudden death of my sister Louise in 1980, and the subsequent effects of grief in family life, moved me towards that resolve. At that point it seemed utterly inadequate to participate in and perpetuate the various concurrent discourses on the shortcomings of photography and issues of representation. While such theoretical matters were hard to avoid in art practice in the 1980s, it seemed to me they could not measure up to the task of explaining the unforgettable qualities of those aerial photographs of the Jonestown dead.

With the radio broadcast of James Reston Jr.’s “Father Cares” on NPR (1981) and the publication of Tim Reiterman’s book, Raven (1982), I started to gain a broader understanding of the Jonestown tragedy, as well as the misinformation and myths that emerged from it. Through most of the eighties decade, I was occupied in my studio with careful examination and replication of Kennerly’s aerial photo in grosspointe embroidery. There was a highly memorable moment early in 1983. A faint wisp of green stuff in Kennerly’s photo quite suddenly and emphatically became a banana leaf. Abstract shards of color soon began to emerge as distinct figures, some with limbs, some with limbs conjoined, apparently expressing terminal gestures of affection and consolation. In this way the subject I chose in 1981, the aerial photograph, seemed to transcend itself and became something else. Perhaps, as others have said, it became hyperreal. I don’t know of any terms that fit the picture precisely as I see it.

Lately I have been occupied in making studies of love. This work requires little more than careful observation and basic video tools. My process involves documenting the day-to-day events that occur in the studio I share with an elderly cat and a willful kitten. My primary tasks are following the cats around with my camera and editing the video recordings to allow for any allegorical associations that might arise. The resulting videos, presented as works of art, show a broad spectrum of affects. Overall, though, I believe these videos can easily be understood as studies of affection and attachment. It seems to me the subject, love, does not call for any more complex treatment than that.

By contrast, the subject of Jonestown insists on more extensive treatment than I could hope to achieve in a work of art.

I owe thanks to David Hume Kennerly, who kindly gave me permission to make use of his Jonestown photographs in my art. The help and patience of many colleagues, friends and family members assisted in the creation of Jonestown Carpet. I am particularly grateful for the encouragement I received throughout the project from my friend and teacher, artist Eric Cameron.

Photographic documentation of Jonestown Carpet and related art works may be viewed at the following web sites:

CCCA Canadian Art Database [Use English portal, then do search for “Jonestown Carpet”]