(Scott Lines, Ph.D. is a Bay Area psychologist-psychoanalyst and writer whose forthcoming book is I’ll Be Your God: The Psychobiography of Jim Jones. He is interested in the psychological underpinnings of Jim Jones, including a close analysis of his early family relations, resulting impact on his character structure, and the manifestations of this character in later life events that resulted in the Jonestown tragedy. In addition to his professional connection to the topic, Scott Lines was born and raised 15 miles from Jones’ birthplace in east-central Indiana. He is interested in hearing from anyone who knew Jim Jones who could add to this characterological study; he can be reached at scottalines@comcast.net.

(Scott Lines, Ph.D. is a Bay Area psychologist-psychoanalyst and writer whose forthcoming book is I’ll Be Your God: The Psychobiography of Jim Jones. He is interested in the psychological underpinnings of Jim Jones, including a close analysis of his early family relations, resulting impact on his character structure, and the manifestations of this character in later life events that resulted in the Jonestown tragedy. In addition to his professional connection to the topic, Scott Lines was born and raised 15 miles from Jones’ birthplace in east-central Indiana. He is interested in hearing from anyone who knew Jim Jones who could add to this characterological study; he can be reached at scottalines@comcast.net.

(Please note that the following is a work-in-progress, is copyrighted, and cannot be used, copied or excerpted in any form without written permission from the author.)

Killers are made, not born.

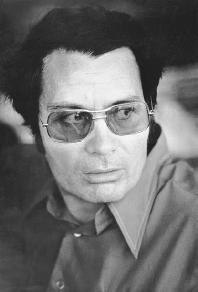

Two photographs bookmark the life of Jim Jones, a life that, to my eye, was all but set in stone by his tenth birthday. In the first, he is about three years old. He’s sitting on the ground, a misshapen lump dropped there, thrown away; his legs almost buckled under him, almost paraplegic. His head is outsized, as if it already holds too much, and looks oddly flattened on one side – did he fall from the sky? Did the left temporal lobe receive the first impact, giving him the twisted preacher-speech cadence that would lift others up, only to fling them from heaven to muddy ground in a forgotten jungle? Or was it the prefrontal cortex that took the hit, leaving him with the twisted judgment and lack of forethought common to any garden-variety American psychopath? There was a twist to his three-year-old body as well, as if some god had reached down where he was planted and given his head a snap. What, pray tell, had bent him so? Perhaps the answer lay in the boy’s face, which pins the viewer with an infection of despair, horror, resignation; the eyes grievous, dark and deep-set, as if ready to shrink from the blow that would come from an unseen hand. The look is accusatory, as if to say, “You, viewer, saw this twisted life and let it happen anyway. You, God, saw this tortured life and looked away. Why hast thou forsaken me?”

The second picture tells a different story. The twist between head and body is gone. Our ten-year-old protagonist stands behind a guitar, smartly dressed in plaid jacket and winter cap, ears covered against the Indiana winter. Behind him lies a desolate small-town tableau of country houses amidst bare trees and mud puddles. Let’s say it is mid-morning, Christmas, 1940. Christmas in Indiana is unpredictable – white and wonderful one year, wet and dreary the next. Let’s say some kindly relative has bestowed upon him the gift of the new guitar, with which Jimmy Jones will captivate the listener’s attention. The body is erect and forward, like a performer’s. He is performing – his mouth set in the most charming of smiles, as if he, alone, knows what the next minute holds. “I’m going to show them who I am,” the boy thinks, and show them he does, mainly through the dark, dazzling eyes. Again, the viewer is pinned, but this time with a dizzying, almost sickening expectation of something miraculous and transformative about to happen, something that will change the quality of things from the inside. His eyes come at you straight, closing the distance between you and him as an irrefutable fact: he and you are one.

Something had transformed him in the span of seven years. This charismatic ten-year-old, who would later orchestrate not only the largest mass murder in American history at Jonestown, but also the only assassination of a U.S. congressman – what made Jim Jones the killer he would become?

Permit me to add a final picture that places Jim Jones in the geography of America, this from Stanley Nelson’s riveting recent documentary film, Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple. The photograph is of a simple water tower, something anyone familiar with small-town America will recognize, if not for the town it signifies, then for its iconic, almost phallic announcement of a place that says, “We, the fathers who bring you The Word, we give you water.” Floating sadly over the photograph, the adult voice of Jim Jones says, “There is a little town in Indiana. The moment I think of it, a great deal of pain comes.” The word, LYNN, stenciled on the four-legged tower in high white letters, signifies Lynn, Indiana, the town directly to the north of my own hometown.

I had known he was born and raised a dozen miles from my birthplace of Richmond, Indiana; perhaps conveniently, I had forgotten exactly how close. Maybe this proximity explains how inexorably, unwillingly mesmerized I am drawn to the cadence, the outright black-Southern Baptist-Elvis drawl that saturates his speech. In the frequent radio broadcasts that air around significant anniversaries of the Jonestown massacre, I hear some bastard version of the mother tongue I was raised around, and yet nothing like speech I grew up hearing on a regular basis. This was speech from the trailer parks, from the night shift of unskilled-worker factories, from the muddiest dirt streets at the edge of town. My town. Like witnessing a horrible traffic accident that you can’t bear to watch yet can’t look away from, like picking painfully at a scab, like pricking up your ears when the neighbors are fighting upstairs, I listen on these anniversaries to the Jonestown recordings, as the Rev. Jim Jones commands 913 of his frightened flock to their deaths on November 18, 1978. “Mother, mother, mother, mother,” Jones sadly chants as he exhorts a Peoples Temple mother, sitting low to the ground below his elevated chair, to not delay in injecting the poisoned Flavor Aid into the mouth of the child she carried at her bosom. “Mother, don’t be that way. Hurry, hurry, my children, hurry! If we can’t live in peace, then let’s die in peace!”

I lean into the radio and fall into a horrible trance.

***

The year was 1978. Four years earlier, President Richard Nixon resigned the highest office in the land under a cloud of humiliation surrounding Watergate. The newly installed president, Gerald Ford, famously said regarding this transition of power that, “Our long national nightmare has ended.” It’s a funny thing about nightmares – they eventually end, and what a relief. But they can return. Four years later, one thousand sleepers were ensconced in a far-flung jungle outpost named after their leader in Guyana, living out a utopian dream-turned-nightmare from which, try as they might, many would never awaken. And, true to the nightmare’s phantasmagorical form, the dreamers didn’t realize they were asleep.

In 1978, I was living out my own utopian fantasy, albeit of a more benign nature, having become involved with Transcendental Meditation a few years earlier. TM, as it is known, was brought to the West by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, a chuckling physicist-turned-guru descended from a two-thousand-year lineage of Vedic masters, who had a flair for hitching his wagon to the dominant cultural signifiers of the moment – the Beatles, Donovan Leitch, Mia Farrow. TM, a simple meditation technique, is practiced by thousands of ordinary people, people you know, who live normal lives and find in their meditations undeniable benefits of peacefulness, harmony and a deeper sense of daily tranquility. One simply closes the eyes and repeats a special word or phrase, a mantra, derived from Sanskrit. The mantra holds no Western meaning, but is revered for its power to deepen mental experience, leading to expanded awareness. On that level of daily practice, TM is useful and beneficial to the practitioner. However, for myself and for thousands of people like me in the 1970s and beyond, it also held illusions of personal enlightenment and world peace that smacked of escapist idealism. Not unlike the early days of Peoples Temple.

Yes, this was the seventies, when utopian ideals were rife on the cultural landscape of America. This epoch was post-almost everything: post-war; post-Hiroshima; post-assassinations, among them the savage killings of John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X; post-civil rights struggles, marches, and riots; post-British Invasion; post-Summer of Love; post-Woodstock; post-Watergate; post-Vietnam. Was the revolution coming, or had it come and gone? No one was certain, but Chairman Mao Zedong’s little red book was required reading. Meanwhile, the People’s Republic of China was demonstrating, through the death-throes of the exhilarating yet murderous, ultimately disastrous Cultural Revolution, what strange bedfellows were socialist fundamentalism and revolutionary zeal. Had that revolution succeeded or failed? It was hard to know. But it was clear that American culture was undergoing a profound shift in values, encompassing new freedoms for women, minorities, and sexuality. At the same time, there was a profound sense of cultural dislocation, alienation and vertigo. Anything from societal transformation to total annihilation seemed within the realm of the possible.

In the midst of this heady brew of social and cultural forces, religious cults made their appearance on the American scene. Moonies, Hare Krishnas, Rajneeshies were everywhere: at airports; on television; coming up the driveway with drums and pamphlets. The TMers were a little more discreet, ever conscious of presenting a “scientific” image. But every group had a solution to the problems of man, and they were particularly adept at ensnaring the young, the alienated, and the disaffected.

In one way, Transcendental Meditation, Buddhism and yogic disciplines are the polar opposite of the more extreme cults, where mind control reigns. No one, to my knowledge, died directly as a result of his or her involvement with the meditation technique or the movement. I’m aware of no more than the usual teacher-disciple sexual transgressions that typify the Catholic Church, certain Christian sects, and the psychotherapies. There were no mass weddings in the Rose Bowl, no black Nikes, no chanting at airports, no plethora of wives in pioneer dress. And yet, several thousand young adults, predominantly white and college-educated, moved around the country and around the world, gathering together for the group coherence, the safety in numbers, and the promise of spiritual enlightenment that came from a closer affiliation to the guru’s teaching and blessings. I was one of them.

The fall from this level of involvement in alternative religious movements to an abject death in the middle of a jungle in Guyana, Peoples Temple’s final chapter, may seem vast. In fact, it may be as simple as the color of one’s skin and the content of one’s wallet. Although the leadership of Peoples Temple consisted of white young adults disaffected from their middle-class backgrounds, the congregation was predominantly African-American. Had I been born black, disadvantaged and churchgoing in Indianapolis, where Peoples Temple was founded, instead of white, privileged and religion-averse sixty miles to the east, I might have found Jones’ mix of socialism and tent-show Christianity compelling. Or, had I heard about this charismatic preacher-healer at a particular nadir in my personal life, and had I been especially seeking, curious or alienated, I might have found company with the reformed hippies who saw something unique, radical and compelling in “Father Jim.”

I’m reminded of a seminal incident that links my benign cult of TM with the death cult of Jonestown. In 1978, living in Indianapolis and trying to find my way to Fairfield, Iowa, to live at the epicenter of the TM movement, I was talking about the news of the Jonestown massacre with Dennis, a friend from my hometown. We had spent two years of mindless debauchery in a fraternity together at Indiana University, leaving that spiritually bankrupt scenario to become blue jeans-wearing, Neil Young-playing hippies “in town.” Living together with another radical ex-Lambda Chi, we avidly sought consciousness expansion in the modes of the early seventies, eventually finding ourselves at a TM introductory lecture. The meditation practice took, and we practiced together for several years. Unlike me, Dennis had no problem donning the three-piece suit that was de rigueur for a TM teacher, and he quickly became more involved than me in the “purity of the teaching.” One such teaching had to do with endeavors such as psychotherapy. Maharishi, the guru, had instructed, “One doesn’t cultivate the negative past. Personal problems are like silt in a glass of muddy water – set the glass aside and the silt will settle to the bottom of the glass, where it won’t trouble you. Don’t stir the water; never entertain negativity.” A near-century of psychotherapy and psychoanalysis discredited with three words from the guru: Never. Entertain. Negativity.

In late November of 1978, the Jonestown massacre was on every front page, every news broadcast. As with millions of other Americans, I was drawn into the horror of the story, mesmerized by the freakish, unthinkable event, and very curious. How could that have happened, I wondered? Seeing the newspaper I’d tossed on the dining room table one morning, Dennis said to me, his tone replete with dire warning, “Don’t read that stuff and don’t watch the television coverage, especially when you’re eating. That stuff is poison.” I thought it a curious prohibition; such restriction of intellectual curiosity didn’t seem to be in keeping with the mood of the time. In fact, it seemed dangerous, a slippery slope tilting in the direction of mindless adherence to dogma. Yes, we were supposed to care for our sensitive nervous systems; we were supposed to let the mud settle, not stir the water. And yet, we lived in a complicated world, vast and occasionally dangerous. Were we to pretend that Jonestown, along with the infinite variety of unspeakable past and future crimes that humankind is capable of, didn’t exist? I think my compulsion to write about Jonestown began in that moment.

Ironically, I found confirmation of the need to know and understand Jonestown’s heart of darkness from none other than Jones himself. In several pictures of the Jonestown pavilion, where the killing took place, one sees the sign Jones prominently displayed behind his chair. It reads:

THOSE WHO DO NOT REMEMBER THE PAST

ARE CONDEMNED

TO REPEAT IT

***

This book, as the title suggests, is a psychobiography of Jim Jones. The spotlight is on his progenitors, his history and his life; on the strange, compelling, poignant, ultimately disastrous phenomenon that was the mind, the personality of Jones. Of course, the members of Peoples Temple and the unfortunate citizens of Jonestown are an elaborate and essential part of the story, thus of this book. Peoples Temple members joined as a response to a vision of individual and collective betterment that was part of a larger cultural thrust in that tumultuous era; they joined for altruistic as well as personal reasons; they joined to be healed by a modern-day Christ figure; they believed.

They were also victims, manipulated, lied to, brainwashed, humiliated, abused, and ultimately killed by Jim Jones. Certainly, their participation in the life of Jonestown was of their choosing; many said it was the best time in their lives. I understand that point of view, having been involved in my own version of a utopian delusion – there’s nothing like group-think to render one’s individual concerns to the dustbin of the personal non-essential, and gladly so: we are One; alone no longer. Why, for instance, on a given Sunday might you find 50,000 or more people on their feet in your average professional sports stadium, screaming as with one voice for the good old home team? Add to that swirling ecstasy, the idea of creating a heaven on earth, and one could imagine how easily hours of involvement turn into days, days into months, months into years. If, on occasion, it does seem like heaven, well then, the leader must be a demi-god, if not God himself. If it does seem hellish at times, the leader will be Virgil, guiding one through the contours of Hell’s proximity, offering salvation’s solution.

In the final analysis, Jim Jones was a delusional, paranoid man who deluded his congregation, eventually killing them. The fact that they participated in his delusion is not their responsibility alone, for they were encouraged in their belief by a charismatic, complicated, in some ways right-spirited, but ultimately destructive malignant narcissist.

A word is in order regarding the psychological lens I will use to examine Jim Jones. My training is as a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst. At a certain point in every psychologist’s or psychotherapist’s life, one or more orientations present themselves with which to view the vast array of psychic phenomena of individual and collective life. One hopes these lenses to be compelling, explanatory and also incomplete, so as to allow for the inclusion of new scientific data. To consider one’s view of the human mind complete is to risk a kind of theoretical fundamentalism in its own right.

My own orientation is broadly described under the rubric of “British object relations,” a dynamic set of theory and clinical practice developed in England by theoreticians working within the British Psycho-analytical Society before and after World War II. Sigmund Freud and several of his closest circle immigrated to London in the late 1930s, under threat of Nazi extermination as Jewish professionals working in Germany, Austria and Hungary. Freud died in London one year later, in 1939, leaving the vast corpus of his life’s work to be dissected, debated and canonized by a disparate group of psychoanalysts in London and elsewhere. These fell into two camps, one led by his daughter, Anna Freud, who considered her father’s work to be essentially complete, and another, led by an Austrian-born psychoanalyst living in London, Melanie Klein. The iconoclastic Mrs. Klein, a non-medically-trained woman in a field dominated by male psychiatrists, nevertheless managed to revolutionize international psychoanalysis. Among other things, her contributions can be seen in bringing to life two additions to Freud’s theory of Eros or dynamic sexuality: the crucial early relationship between mother and infant; and a drive opposite to Freud’s sexual Eros – the death drive, Thanatos. The death drive will be one key psychological component I will use to explain the life and death of Jim Jones. As we shall see, his stunning investment in bringing life to, then over the brink of death, into “the orgasm of the grave,” cannot be explained in terms of life and Eros alone. In addition to the death drive, four other key psychological components will be used to analyze the life and death of Jim Jones, which I’ll only mention here. They are: Freud’s conception of the Oedipus complex, which he thought to be a fundamental structuring force in the life of the individual and family, and which has undergone substantial revision in modern times; the function of projection as a primitive mechanism to rid the psyche of troubling emotions; the conception ofpathological organization, a feature of the primitively organized psyche that utilizes a Mafia-type of internal structure to manage the vicissitudes of living; and malignant narcissism, a descriptive concept applicable to certain sociopaths, like Jones, whose aggressivity, lack of empathy and lack of a conscience make them dangerously charismatic and charismatically dangerous.

Ultimately, I do not consider Jim Jones devoid of humanity. While it would be easy to hate him, it is much more complicated, and, I think, more interesting as a study of the human condition, to struggle to understand him, and in so doing, understand how killers are made, not born. My compulsion to write about Jones and Jonestown resides somewhere within the desire to explore the dangers of delusions of enlightenment split off from, yet preoccupied, even saturated with the death drive; to tell the story of an individual psyche shaped by inexorable destructive forces in a family and a society; to explore the human tendency to group together lemming-like in the shadow of the abyss; and finally, to provide within this story of one man and his followers a cautionary tale about the delusions of fundamentalist certainty.