“Jim Jones is one the state’s most politically potent leaders. But who is he? And what’s going on behind his church’s locked doors?.”

For Rosalynn Carter, it was the last stop in an early September campaign tour that had taken her over half of California, a state where her husband Jimmy was weak. So Rosalynn gamely encouraged the crowd of 750 that had gathered for the grand opening of the San Francisco Democratic party headquarters in a seedy downtown storefront. She smiled bravely despite the heat.

Mrs. Carter finished her little pep talk to mild applause. Several other Democratic bigwigs got polite receptions, too. Only one speaker aroused the crowd; he was the Reverend Jim Jones, the founding pastor of Peoples Temple, a small community church located in the city’s Fillmore section. Jones spoke briefly and avoided endorsing Carter directly. But his words were met with what seemed like a wall-pounding outpour. A minute and a half later the cheers died down.

“It was embarrassing,” said a rally organizer. “The wife of a guy who was going to the White House was shown up by somebody named Jones.”

If Rosalynn Carter was surprised, she shouldn’t have been. The crowd belonged to Jones. Some 600 of the 750 listeners were delivered in temple buses an hour and a half before the rally. The organizer, who had called Jones for help, remembered how gratified she’d felt when she first saw the Jones followers spilling off the buses. “You should have seen it – old ladies on crutches, whole families, little kids, blacks, whites. Made to order,” said the organizer, who had correctly feared that without Jones Mrs. Carter might have faced a half-empty room.

“Then we noticed things like the bodyguards,” she continued. “Jones had his own security force [with him], and the Secret Service guys were having fits,” she said. “They wanted to know who all these black guys were, standing outside with their arms folded.”

The next morning more than 100 letters arrived. “They were really all the same,” she said. “‘Thanks for the rally, and, say, that Jim Jones was so inspirational.’ Look, we never get mail, so we notice one letter, but 100?” She added, “They had to be mailed before the rally to arrive the next day.”

But what surprised that organizer was really not that special. She just got a look at some of the methods Jim Jones has used to make himself one of the most politically potent religious leaders in the history of the state.

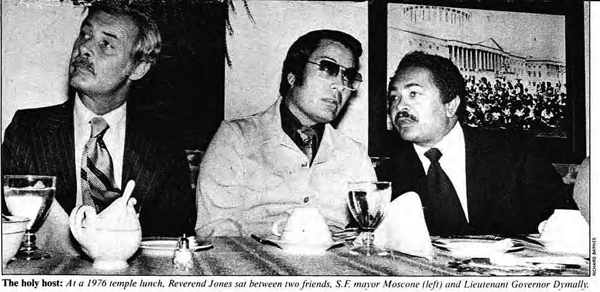

Jim Jones counts among his friends several of California’s well-known public officials. San Francisco mayor George Moscone has made several visits to Jones’s San Francisco temple, on Geary Street, as have the city’s district attorney Joe Freitas and sheriff Richard Hongisto. And Governor Jerry Brown has visited at least once. Also, Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley has been a guest at Jones’s Los Angeles temple. Lieutenant Governor Mervyn Dymally went so far as to visit Jones’s 27,000-acre agricultural station in Guyana, South America, and he pronounced himself impressed. What’s more, when Walter Mondale came campaigning for the vice-presidency in San Francisco last fall, Jim Jones was one of the few people invited aboard his chartered jet for a private visit. Last December Jones was appointed to head the city’s Housing Authority Commission.

The source of Jones’s political clout is not very difficult to divine. As one politically astute executive puts it: “He controls votes.” And voters. During San Francisco’s run-off election for mayor in December of 1975, some 150 temple members walked precincts to get out the vote for George Moscone, who won by a slim 4,000 votes. “They’re well-dressed, polite and they’re all registered to vote,” said one Moscone campaign official.

Can you win office in San Francisco without Jones? “In a tight race like the ones that George or Freitas or Hongisto had, forget it without Jones,” said State Assemblyman Willie Brown, who describes himself as an admirer of Jones’s.

Jones, who has several adopted children of differing racial backgrounds, is more than a political force. He and his church are noted for social and medical programs, which are centered in his three-story structure on Geary Street. Temple members support and staff a free diagnostic and outpatient clinic, a physical therapy facility, a drug program that claims to have rehabilitated some 300 addicts and a legal aid program for about 200 people a month. In addition, the temple’s free dining hall is sad to feed more indigents than the city’s venerable St. Anthony’s dining room. And temple spokesmen say that these services to the needy are financed internally, without a cent of government or foundation money.

Jones and his temple are also applauded for their ardent support of a free press. Last September, Jones and his followers participated in a widely publicized demonstration in support of the four Fresno newsmen who went to jail rather than reveal their confidential news sources. The temple also contributed $4,400 to twelve California newspapers – including the San Francisco Chronicle – for use “in the defense of a free press,” and once gave $4,000 to the defense of Los Angeles Times reporter Bill Farr, who also went to jail for refusing to name a news source.

In addition, at Jones’s direction the temple makes regular contributions to several community groups, including the Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Center and Health Clinic, the NAACP, the ACLU and the farmworkers’ union. When a local pet clinic was in trouble, Peoples Temple provided the money needed to keep it open. The temple has also set up a fund for the widows of slain policemen, and the congregation runs an escort service for senior citizens.

To many, the Reverend Jim Jones is the epitome of a selfless Christian.

The reverend was born James Thurman Jones, and grew up in the Indiana town of Lynn. While attending Butler University in Indianapolis, where he received his degree in education, Jones opened his first temple (in downtown Indianapolis). Although he had no formal training as a minister and was not affiliated with any church, his temple grew. It featured an active social program, including a “free” restaurant for the down-and-out. And the congregation was integrated, a courageous commitment in the years before Martin Luther King became a national figure – particularly in Indianapolis, once the site of the Ku Klux Klan’s national office.

Then at around Christmas of 1961, according to a former associate named Ross Case, Jones had a vision. He saw Indianapolis being consumed in a holocaust, presumably a nuclear explosion. Fortunately for him, Esquire had just run an article on the nine safest spots in the event of nuclear war. Eureka, California, was called the safest location; another safe area was Belo Horizante, Brazil. Jones headed for Belo Horizante, and Case went to Northern California.

Jones eventually returned and visited Case in Ukiah. Jones liked California, and twelve years ago this month, he and his wife Marceline incorporated Peoples Temple in California; Jones and some 100 faithful settled in Redwood Valley, a hamlet outside Ukiah.

Jones’s congregation grew, and he soon became a political force in Mendocino County. In off-year elections, where the total vote was around 2,500, Jones could control 300 to 400 ballots, or nearly 16 percent of the vote. “I could show anybody the tallies by precinct and pick out the Jones vote,” says Al Barbero, county supervisor from Redwood Valley.

Then, in 1970, Jones started holding services in San Francisco; one year later he bought the Geary Street temple. And later that same year, he expanded to Los Angeles by taking over a synagogue on South Alvarado Street.

One success followed another, and his flock grew to an estimated 20,000. Jones’s California mission seemed blessed.

Although Jones’s name is well-known, especially among the politicians and the powerful, he remains surrounded by mystery. For example, his Peoples Temple has two sets of locked doors, guards patrolling the aisles during services and a policy of barring passersby from dropping by unannounced on Sunday mornings. His bimonthly newspaper, Peoples Forum, regularly exalts socialism, praises Huey Newton and Angela Davis and forecasts a government takeover by American Nazis. And though Jones is a white fundamentalist minister, his congregation is roughly 80 percent to 90 percent black.

How does Jones manage to appeal to so many kinds of people? Where does he get the money to operate his church’s programs, or maintain his fleet of buses, or support his agricultural outpost in Guyana? Why does he surround himself with bodyguards – as many as fifteen at a time? And above all, what is going on behind the locked and guarded doors of Peoples Temple?

Beginning two months ago, when it became known that New West was researching an article on Peoples Temple, the magazine, its editors and advertisers were subjected to a bizarre letter-and-telephone campaign. At its height, our offices in San Francisco and Los Angeles were each receiving as many as 50 phone calls and 70 letters a day. The great majority of the letters and calls came from temple members and supporters, as well as such prominent Californians as Lieutenant Governor Mervyn Dymally, Delancey Street [Foundation] founder John Maher, San Francisco businessman Cyril Magnin, and savings and loan executive Anthony Frank. The messages were much the same: We hear New West is going to attack Jim Jones in print; don’t do that. He’s a good man who does good works.

The flood of calls and letters attracted wide attention, which, in turn, prompted newsman Bill Barnes to report the campaign in the San Francisco Examiner. The Examiner also reported an unconfirmed break-in one week later at our San Francisco office.

After the Barnes article, we began getting phone calls from former temple members. At first, while insisting on anonymity, the callers volunteered “background” about Jim Jones’s “cruelty” to congregation members, in addition to making several other specific charges.

We told the callers that we were not interested in such anonymous whispers. But then a number of them, like Deanna and Elmer Mertle, called back and agreed to meet in person, to be photographed, and to tell their attributed stories for publication.

Based on what these people told us, life inside Peoples Temple was a mixture of Spartan regimentation, fear and self-imposed humiliation. As they told it, the Sunday services to which dignitaries were invited were orchestrated events. Actually, members were expected to attend services two, three, even four nights a week – with some sessions lasting until daybreak. Those members of the temple’s governing council, called the Planning Commission, were often compelled to stay up all night and submit regularly to “catharsis” – an encounter process in which friends, even mates, would criticize the person who was “on the floor.” In the last two years, we were told, these often humiliating sessions had begun to include physical beatings with a large wooden paddle, and boxing matches in which the person on the floor was occasionally knocked out by opponents selected by Jones himself. Also, during regularly scheduled “family meetings,” attended by up to 1,000 of the most devoted followers, as many as 100 people were lined up to be paddled for such seemingly minor infractions as not being attentive enough during Jones’s sermons. Church leaders also instructed certain members to write letters incriminating themselves in illegal and immoral acts that never happened. In addition, temple members were encouraged to turn over their money and property to the church and live communally in temple buildings; those who didn’t ran the risk of being chastised severely during the catharsis sessions.

In all, we interviewed more than a dozen former temple members. Obviously they all had biases. (Grace Stoen, for example, has sued her husband, a temple member, for custody of their five-year-old son John. The child is reportedly in Guyana.) So we checked the verifiable facts of their accounts – the property transfers, the nursing and foster home records, political campaign contributions and other matters of public record. The details of their stories checked out.

One question, in particular, troubled us: Why did some of them remain members long after they became disenchanted with Jones’s methods and even fearful of him and his bodyguards? Their answers were the same – they feared reprisal, and that their stories would not be believed.

The people we interviewed are real; their names are real. They all agreed to be tape-recorded and photographed while telling their side of the Jim Jones story.

They beat his daughter badly: Elmer Mertle.

After Elmer and Deanna Mertle joined the temple in Ukiah in November, 1969, he quit his job as a chemical technician for Standard Oil Company, sold the family’s house in Hayward and moved up to Redwood Valley. Eventually five of the Mertle’s children by previous marriages joined them there.

“When we first went up [to Redwood Valley], Jim Jones was a very compassionate person,” says Deanna. “He taught us to be compassionate to old people, to be tender to the children.”

But slowly the loving atmosphere gave way to cruelty and physical punishments. Elmer said, “The first forms of punishment were mental, where they would get up and totally disgrace and humiliate the person in front of the whole congregation. . . . Jim would then come over and put his arms around the person and say, ‘I realize that you went through a lot, but it was for the cause. Father loves you and you’re a stronger person now. I can trust you more now that you’ve gone through and accepted this discipline.’”

The physical punishment increased too. Both the Mertles claim they received public spankings as early as 1972 – but they were hit with a belt only “about three times.” Eventually, they said, the belt was replaced by a paddle and then by a large board dubbed “the board of education,” and the number of times adults and finally children were struck increased to 12, 25, 50 and even 100 times in a row. Temple nurses treated the injured.

At first, the Mertles rationalized the beatings. “The [punished] child or adult would always say, ’Thank you, Father,” and then Jim would point out the week how much better they were. In our minds we rationalized … that Jim must be doing the right thing because these people were testifying that the beatings had caused their life to make a reversal in the right direction.”

Then one night the Mertles’ daughter Linda was called up for discipline because she had hugged and kissed a woman friend she hadn’t seen in a long time. The woman was reputed to be a lesbian. The Mertles stood among the congregation of 600 or 700 while their daughter, who was then sixteen, was hit on her buttocks 75 times. “She was beaten so severely,” said Elmer, “that the kids said her butt looked like hamburger.”

Linda, who is now eighteen, confirms that she was beaten: “I couldn’t sit down for at least a week and a half.”

The Mertles stayed in the church for more than a year after that public beating. “We had nothing on the outside to get started in,” says Elmer. “We had given [the church] all our money. We had given all of our property. We had given up our jobs.”

Today the Mertles live in Berkeley. According to an affidavit they signed last October in the presence of attorney Harriet Thayer, they changed their names legally to Al and Jeanne Mills because, at the church’s instruction, “we had signed blank sheets of paper, which could be used for any imaginable purpose, signed power of attorney papers, and written many unusual and incriminating statements [about themselves], all of which were untrue.”

“I never really thought he was God, like he preached, but I thought he was a prophet,” said Birdie Marable, a beautician who was first attracted to Jones in 1968 because her husband had a liver ailment. She had hoped Jones might be the healer to save him.

On one of the trips to services in Redwood Valley, Marable noticed Jones’s aides taking some children aside and asking, “What color house did my friend have, things like that,” she says. “Then during the services, Jim called [one woman] out and told her the answers that the children had given as though no one had told him.”

She became skeptical of Jones after that, and remained skeptical when her husband’s health did not improve; the cancer “cures” Jones was performing seemed phony to her. Yet eventually she moved to Ukiah and ran a rest home for temple members at Jim’s suggestion.

One summer she was talked into taking a three-week temple “vacation” through the South and East. “Everybody paid $200 to go on the trip, but I told them I wasn’t able to do so,” she added.

The temple buses were loaded up in San Francisco, and more members were packed aboard in Los Angeles. “It was terrible. It was overcrowded. There were people sitting on the floor, in the luggage rack, and sometimes people [were] underneath in the compartment where they put the bags,” she said. “I saw some things that really put me wise to everything,” she added. “I saw how they treated the old people.” The bathrooms were frequently stopped up. For food, sometimes a cold can of beans was opened and passed around.

“I decided to leave the church when I got back. I said when I get through telling people about this trip, ain’t nobody going to want to go no more. [But] as soon as we arrived back, Jim said . . . ‘don’t say nothing.” She left the church in silence.

Wayne Pietila and Jim Cobb guarded the cancers. “If anyone tried to touch them, we were supposed to eat the cancers or demolish the guy,” said Cobb, who is six-feet, two-inches tall. Pietila was licensed by the Mendocino County Sheriff’s Department to carry a concealed weapon; reportedly he was one of several Jones aides with such a permit.

It was during the Redwood Valley healing sessions in 1970, when nervous hope for relief from the pains of age spread among the congregation, that Cobb and Pietila would guard the cancers. Finally Jones would ask for someone who believed herself to be suffering from cancer. That was the signal for Cobb’s sister, Terri, to slip into a side restroom and shoo out whoever might be there. Then Jones’s wife Marceline and a trembling excited old woman would disappear into the stall for a moment. Marceline would emerge holding a foul-smelling scrap of something cupped in a napkin – a cancer “passed.” Marceline and the old woman would return to the main room to screams, applause, a thunder of music. Jim Jones had healed again.

But one time, Terri got a chance to look into the “cancer bag.” “It was full of napkins and small bits of meat, individually wrapped. They looked like chicken gizzards. I was shocked.”

Wayne Pietila recalled another healing incident. On the eve of a trip to Seattle in 1970 or 1971, as Jones was leaving his house, a shot cracked out and he fell. “There was blood all around and people [were] screaming and crying, just hysterical.” Jones was lifted to his feet and helped to his house. A few minutes later, Jones walked out of the house with a clean shirt on. “He said he’d healed himself,” Pietila said. “He used [the incident] for his preaching during the whole Seattle trip.”

The Touchette family followed Jones to California in 1970. They lived in Stockton for a while, then moved up to Redwood Valley, where they bought a house and converted it into a home for emotionally disturbed boys.

During 1972 and 1973 Micki and other temple members were expected to travel to Los Angeles services every other weekend. One of her jobs was to count the money after offerings. Micki, a junior college graduate, had the combination to the temple’s Los Angeles safe. She says. “It was very simple to take in $15,000 in a weekend, and this was [four] years ago. [To encourage larger offerings, Jones] would say, ‘We folks, we’ve only collected $500 or $700,’ and we would have [in reality] several thousand.”

In addition to attending Wednesday night family meetings and weekend services, Micki also was part of letter-writing efforts directed by church officials. “We’d write various politicians throughout the state, throughout the country, in praise of something that they had done. I wrote Nixon, wrote Tunney; I remember writing the chief of the San Francisco Police Department,” she said. Micki, who lived in temple houses apart from her parents, would often be handed a sheet listing the points she would have to include in the letter. “It would tell you how and what to say and you’d word it yourself.” She says she also would regularly use aliases she made up.

When Micki left the church in 1973 along with seven other young people, including Terri and Jim Cobb and Wayne Pietila, none warned their parents or other relatives. “We felt that our parents, our families . would just fight us and try to make us stay.” Furthermore, they were all frightened. “At one point we had been told that any college student who was going to leave the church would be killed . not by Jones, but by some of his followers.” Both Terri and Cobb recall the statement being made – by Jones.

When Walt Jones, who never believed in the church, followed his wife Carol to Redwood Valley in 1974, Jim Jones asked them to take over a home for emotionally disturbed boys. The home belonged to Charles and Joyce Touchette, Micki Touchette’s parents. Walt says he was told that the Touchettes were in Guyana, and that the people who had replaced them, Rick and Carol Stahl, had done such a poor job that “the care home, at that time, was under surveillance of the authorities because of the poor conditions. Some of the boys had scabies due to the filth.”

In 1974 and early 1975, before Walt and his wife were granted a license to run the home, county checks (of approximately $325 to $350 per month for each child) for the upkeep of the boys were made out to the Touchettes and cashed by a church member who had their power of attorney. “The checks,” said Walt, “were turned over to someone in charge of all the funds [for the church’s care homes] at the time. [The temple] allotted us what they felt were sufficient funds for the home and supplied us with foodstuffs and various articles of clothing.” Jones says the food was mostly canned staples, and the clothes were donations from other temple members. Walt is uncertain how much of the approximate total of $2,000 a month of county funds earmarked for the upkeep of his boys actually ended up in his hands; his wife kept the books. But, he claimed, “it was very inadequate.”

After the Joneses were granted their own license in 1975, the checks from the Alameda County Probation Department (which placed the boys in the home) were made out to him and his wife. “But still the church requested that we turn over what remained of the funds,” says Walt Jones. “Approximately $900 to $ 1,000 [per month] were turned over to the church.” And he added, “I do remember that there were times when all of the checks were signed over to the church.”

They took her best watch: Laura Cornelious.

Laura Cornelious was one of the privates in the Peoples Temple’s army. She was in the temple about five years before leaving in 1975 – just one of dozens of elderly black grandmothers who attend each meeting of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission that Jim Jones chairs.

The first thing that bothered her was the constant requests for money. “After I was in some time,” she says, “it was made known to us that we were supposed to pay 25 percent of our earnings [the usual sum, according to practically all the former members that we interviewed].” It was called “the commitment.” For those who could not meet the commitment, she says, there were alternatives, like baking cakes to sell at Sunday services – or donating their jewelry. “He said that we didn’t need the watches – my best watch,” she recalls sadly. “He said we didn’t need homes – give the homes, furs, all of the best things you own.”

Some blacks gave out of fear – fear that they could end up in concentration camps. The money was needed, she was told, “to build up this other place [Guyana-the ‘promised land’], so we would have someplace to go whenever they [the fascists in this country] were going to destroy us like they did the Jews. [Jones said] that they would put [black people] in concentration camps, and that they would do us like the Jews . in the gas ovens.”

Laura Cornelious was also bothered by the frisking of temple members (but never dignitaries) before each service. “You even were asked to raise up on your toes [to check] your shoes.”

The final straw, she says, came the night Jones brought a snake into the services. “Viola . she was up in age, in her eighties, and she was so afraid of snakes and he held the snake close to her [chest] and she just sat there and screamed. And he still held it there.”

They have her five-year-old boy: Grace Stoen.

Grace Stoen was a leader among the temple hierarchy, though she was never a true believer. Her husband Tim was the temple’s top attorney, and one of its first prominent converts. Later, while still a church insider, he became an assistant D.A. of Mendocino County, and then an assistant D.A. under San Francisco D.A. Joe Freitas. Tim resigned to go to Jones’s Guyana retreat in April of this year.

Grace agreed to join the temple when she married Tim in 1970, and gradually she acquired enormous authority. She was head counselor, and at the Wednesday night family meetings, she would pass to Jones the names of the members to be disciplined.

She was also the record keeper for seven temple businesses. She paid out from $30,000 to $50,000 per month for the auto and bus garage bills and also doled out the slim temple wages. And she was one of several church notaries. She kept a notary book, a kind of log of documents that she officially witnessed-pages of entries including power-of-attorney statements, deeds of trust, guardianship papers, and so on, signed by temple members and officials.

She recalled why Jones decided to aim for Los Angeles and San Francisco. “Jim would say, ‘If we stay here in the valley, we’re wasted. We could make it to the big time in San Francisco.”

And expanding to Los Angeles , Jones told his aides, “was worth $15,000 to $25,000 a weekend.”

During the expansion in 1972, members would pile into the buses at 5 P.M. on a Friday night in Redwood Valley, stop at the San Francisco temple for a meeting that might last until midnight and then drive through the night to arrive in Los Angeles Saturday in time for six-hour services. On Sunday, church would start at 11 A.M. and end at 5 P.M. Then, the Redwood Valley members would pile back on the buses for the long trip home; they would arrive by daybreak Monday.

Some of the inner circle, like Grace Stoen, rode on Jim’s own bus, number seven. “The last two seats and the whole back seat were taken out and a door put across it,” she said. “Inside there was a refrigerator, a sink, a bed and a plate of steel in the back so nobody could ever shoot Jim. The money was kept back there in a compartment.” According to attendance slips she collected, the other 43-seat buses sometimes held 70 to 80 riders.

Jones’s goal in San Francisco, Grace said, was to become a political force. His first move was to ingratiate himself with fellow liberal and leftist figures D.A. Freitas, Sheriff Hongisto, Police Chief Charles Gain, Dennis Banks, Angela Davis.

Sometimes Jones nearly tripped up. Once, said Grace, when Freitas and his wife dropped in unexpectedly, temple aides quickly pulled them into a side room and sent word to Jones in the upstairs meeting hall. Just in time. The pastor was wrapped up in one of his “silly little things,” said Grace. “He was having everybody shout ‘Shit! Shit! Shit!’ to teach them not to be so hypocritical.” When Freitas was shown in, everyone just laughed at the puzzle district attorney. (D.A. Freitas confirms making an unexpected visit to the temple, but does not recall anyone using the word shit.)

Jones became impatient at the pace his success. Eventually Mayor Moscone placed Jones on the Housing Authority Commission, and then intervened to assure him the chairmanship.

Strangely, as Jones’s successes mounted, so did the pressures inside his temple. “We were going to more and more meetings,” said Stoen. “[And] if anyone was getting too much sleep – say, six hours a night – they were in trouble.” On one occasion, she said, a man was vomited and urinated on.

In July of 1976, after a three-week temple bus trip, her morale was ebbing lower, her friends were muttering about her, and there were rumors that Jones was unhappy with a number of members. “I packed my things and left [without telling Tim]. I couldn’t trust him. He’d tell Jim.”

She drove to Lake Tahoe and spent the July Fourth weekend lying on a warm beach. She dug her toes in the sand, stretched her arms and tried to relax. “But every time I turned over, I looked around to see if any of the church members had tracked me down.”

It is literally impossible to guess how much money and property people gave Jim Jones in the twelve years since he moved his Peoples Temple to California. Some, like Laura Cornelious, gave small things like watches or rings. Others, like Walt Jones, sold their homes and gave the proceeds to the temple.

According to nearly all the former temple members that we have spoken with, extensive, continuous pressure was put on members to deed their homes to the temple. Many complied. A brief reading of the records on file at the Mendocino County recorder’s office shows that some 30 pieces of property were transferred from individuals to the temple during the years 1968 to 1976. Nearly all these parcels were recorded as gifts.

Interestingly, several of the “gifts” were signed or recorded improperly. The deed to a piece of property signed by Grace and Timothy Stoen was notarized on June 20, 1976. Grace Stoen told New West that on that date, when she was supposed to be in Mendocino signing the deed before a temple notary, she and several hundred temple members were in New York City. Grace Stoen said she signed the deed under pressure from her husband, Tim, months before it was notarized. And similar irregularities appear on a deed the Mertles turned over to the temple. A thorough investigation of the circumstances surrounding the transfers of the properties is clearly required.

In the last few issues of Peoples Forum, the temple newspaper, there are several references to the claim that 130 disturbed or incorrigible youths were being sent to the temple’s Guyana mission. A church spokesman confirmed that these youngsters were released to the temple by “federal courts, state courts, probation departments” and other agencies. An article in the July issue of the temple newspaper on the Guyana mission’s youth program reports that, “In certain cases when a young person is testing the environment . physical discipline has produced the necessary change.” The article goes on to describe a “wrestling match” that sounds all too similar to the “boxing matches” some former temple members described. If there is even the slightest chance of mistreatment of the 130 youths the temple claims to have under its guidance in Guyana, a complete investigation by both state and federal authorities would be required.

An investigation of the “care homes” run by the temple or temple members in Redwood Valley may also be in order. Both Walt Jones and Micki Touchette have stated that anywhere from $800 to $ 1,000 of the monthly funds provided by the state for the care of the six boys in the Touchette home were actually funneled to the temple. If those figures are accurate, as much as $38,000 to $48,000 may have been channeled into the church’s coffers during the four years the Touchette home was open. It is known that at least two other “care homes ”for boys were run by the church or its members. In addition, at least six residential homes licensed by Mendocino County were owned or operated by the temple. They housed from six to fourteen senior citizens each, and the county provided upwards of $325 per month per individual. An investigation should be launched immediately to determine if any of the money paid for the care of the elderly actually went to the temple.

Files at the Mendocino County recorder’s office show that the temple has sold off a number of its properties. The Redwood Valley temple itself is currently for sale for an estimated $225,000. The Los Angeles temple is also for sale. The three Mendocino “care homes” that are still operating are up for sale. Several former temple members believe Jones and a few hundred of his closest followers may be planning to leave for Guyana no later than September of this year. The ex-members we interviewed had the ability to walk away from the temple once they found the courage to do it. Whether the church will permit those who move to Guyana the option of ever leaving is questionable.

Jones has been in Guyana for the last three weeks and was unavailable to us as this magazine article went to press. In a phone interview, two spokesmen for the temple, Mike Prokes and Gene Chaikin, denied all of the allegations made by the former temple members we interviewed. Specifically, they denied any harassment, coercion or physical abuse of temple members. They denied that the church attempted to force members to donate their property or homes. They also denied that Jones faked healings. They confirmed that the temple’s churches and property in Redwood Valley and Los Angeles are for sale, but went on to deny that Jones’s closest followers are planning to relocate Guyana any time soon.

Finally, something must be said about the numerous public officials and political figures who openly courted and befriended Jim Jones. While it appears that none of the public officials from Governor Brown on down knew about the inner world of Peoples Temple, they have left the impression that they used Jones to deliver votes at election time, and never asked any questions. They never asked about the bodyguards. Never asked about the church’s locked doors. Never asked why Jones’s followers were so obsessively protective of him. And apparently, some never asked because they didn’t want to know.

The story of Jim Jones and his Peoples Temple is not over. In fact, it has only begun to be told. If there is any solace to be gained from the tale of exploitation and human foible told by the former temple members in these pages, it is that even such a power as Jim Jones cannot always contain his followers. Those who left had nowhere to go and every reason to fear pursuit. Yet they persevered. If Jones is ever to be stripped of his power, it will not be because of vendetta or persecution, but rather because of the courage of these people who stepped forward and spoke out.

Caption: p. 31

The holy host: At a 1976 temple lunch, Reverend Jones sat between two friends, S.F. mayor Moscone (left) and Lieutenant Governor Dymally.

Callouts:

Page 34

“.Peoples Temple members beat his sixteen-year-old daughter so badly, says Elmer Mertle, that ‘her butt looked like, hamburger’.”

Page 36

“.Jones held a snake close to the terrified old woman. ‘Viola screamed,’ said a member. ‘And he still held that snake there’.”

Page 38

“. . . ‘Jones would say that we could make it in, the big time,’ says Grace Stoen. ‘Expanding to L.A. alone was worth $15,000 a weekend’ .”

San Francisco Chronicle Reporter Marshall Kilduff and New West contributing editor Phil Tracy were assisted by freelance newsman George Klineman.