(Stephan Jones is a frequent contributor to the jonestown report. His other writings for this website appear here. He may be reached at moreheart1@comcast.net.)

(Stephan Jones is a frequent contributor to the jonestown report. His other writings for this website appear here. He may be reached at moreheart1@comcast.net.)

When I first met Carolyn, I wanted her to like me and go away forever. I don’t remember ever feeling any real animosity toward her. I’m also pretty sure I felt no warmth. Sympathy maybe, or empathy. Curiosity, for sure. But I definitely wanted her to leave us alone. Us, that mess I called a family. Yeah, I wanted her to go away most of the time, and I’m pretty sure she wanted the same from me. We stirred each other’s conscience and wanted conflicting things from the same man.

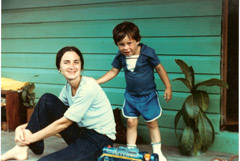

There was no real connection between us, or desire to have one, until Kimo came along. He was my little brother and she was his mom, and that changed things. Kimo changed a lot for me. I enjoyed that little booger so much, especially when I could be with him outside the forced family unit that Dad was determined to establish with his newest woman. When it was just Kimo and me, somehow I was happy. And I couldn’t completely deny Carolyn’s contribution to that, especially since she so obviously adored Kimo, and he her. In the teeter-totter of my relationship with Carolyn, Kimo became the fulcrum that balanced us.

Carolyn was kind of just there for me. See, while it seemed that most everyone was blaming everyone around Dad for the ills of the Temple, almost from the day I met Carolyn, I found it hard to blame anyone but Dad. So Carolyn was just there, along for Dad’s ride like the rest of us.

I remember hanging out with her in Willits one odd day, all of “The Boys” – Lew, Jimmy, Tim, and myself. I think it was before she became pregnant with Kimo, before her long disappearance on a fabricated mission so that her impregnation could be at the hand of an enemy rather than our perfect leader. Our little get together was all arranged by Dad, who coached us perfectly on what the ideal behavior and outcome would be. We all really tried to put on a good show. We did want to please. But I remember feeling like Carolyn wanted to get out of there just as much as I did. And I wanted her to like me and she wanted us to like her and we all wanted to like each other, but all of us on our own terms. So we stumbled and mumbled about and got it over with. She was so young, how could she possibly know how to navigate Dad.

I guess she learned.

After a few months in Jonestown, it was clear to me that she was more expert than most of us at making her way down that uncharted, wild, poisoned river that was my father’s life. Of course, I think she’d be the first to say that a much better course would’ve been to make her way to the closest bank any way she could the minute the waters started getting choppy and the paddle had somehow made its way into Dad’s hands. It felt to me like Carolyn quickly got hard and cynical and more prominently involved, so she couldn’t help but catch some fire as I aimed my disdain and disgust at Dad. But there was this little boy named Kimo that granted her some immunity from my default setting of rage.

That rage darkened my vision then and left cataracts on my memory. But one thing I do recall with clarity: when Dad no longer cared about the new family unit, and his desire for me to spend time with Carolyn was no longer required or enforceable, I didn’t. But I watched her. I was still curious. I knew Carolyn to be smart – even intuitive, and in many ways solid. Even with all the wrong she rationalized, she somehow struck me as a person of character. So, I watched her. A part of me needed to know if she really bought all of Dad’s incredibly obvious games, deceptions, and general bullshit. I needed to know why she hung in there, why, even though I could tell that she’d had enough in so many ways, she toed the party line and did her man’s bidding.

He was her baby’s Papa – the profound meaning of this was no doubt warped and magnified for Carolyn when everyone came to know about it after the story of how Carolyn came to be with child went from an enemy’s doing to Dad’s, an accident as he trained Carolyn on how to use her body for the cause while on that same fictitious mission. But most important was the bond of parenthood. Carolyn had given herself to my father and taken from others to do it. For the sake of Jim Jones – for the love of Jim Jones – she had turned her back on, even demonized, incredibly good people whom she loved dearly. Maybe she got lost in the myopic belief that only she stood a chance of getting things – getting him – back on track. She had to. Otherwise, how could she live with herself?

No, it was more than that. I saw Carolyn, just like Mom but in her own way, try to manage Dad while she fixed him. And then she was lost. Trying to fix someone who doesn’t know they need fixing by playing their game on their court…

After everyone died, I knew before the witnesses told me that Carolyn was heavily involved in those deaths. I knew that she had a big part in the terror my little brother felt in the hours before she took his life and then her own. But I cannot remember feeling angry at her. It’s true that all my rage gathered itself, fed on itself and pummeled relentlessly the memory that was my father. Hatred. So much of it so that I would not have to face my own shame and acknowledge the hatred I felt for myself. There was little ill will left for others, which may have let Carolyn off the hook, but I managed to muster plenty – more than anyone deserved – for a select few. But not Carolyn. I know I couldn’t let go of the kindred innocence I felt the first time I met her, but that was just a small part of what shielded her from my ugliness. There was something more, much greater.

Historical Society, MSP 3800

I think it was Kimo. I loved that wide open, clumsy, frog-voiced boy so much. And I was not there for him when he needed me most.

I had this picture of him, just an amazing shot, captured him beautifully – I’d bet Gene Chaikin took it as he plodded about in his and the Temple’s last days – my little brother looking intently through a fence, staring down the camera, his chubby left cheek pressed against the same vertical slat his knuckleless left fist is wrapped around. A poise that didn’t belong on such a round, smooth face, but fit perfectly the rascal who used to soldier crawl through Dad’s San Francisco apartment – Kimo never did the hands and knees thing – slamming door knobs against walls as he went from one room to the next.

How do you say goodbye to that? I don’t think I ever have. I know I don’t have the picture anymore. I’m certain I lost it because every time I looked at it – and I had to look at it – my heart and lungs and throat were squeezed so tightly that it felt like it was their juices pouring from my eyes until no more would come and my mouth was cotton.

Carolyn was his Mama, and he adored her and she him, and that gave her this special untouchable seat just off the edge of my grief. That she gave me Kimo far outweighed that she took him away. Of course, I see it differently now. My understanding of responsibility has shifted. I now accept – or at least know that I should accept – what has been laid out. I also have come to know Carolyn’s lovely family, and they have shared with me the Carolyn they knew before she entered the Temple and in their diminishing private moments after, and I am forever in their debt for this.

Carolyn’s and my first meeting has now taken place at an earlier, more innocent, unstained and unstrained time. And the child, adolescent, and young woman that greets me is lovely indeed, deserving of nothing but my appreciation and compassion.

May you rest in peace, dear Carolyn, you and that little boy who knew you best and loved you most.