To read the German translation of this article, click here.

Eine deutsche Übersetzung dieses Texts finden Sie hier.

(Barbara Moore, the wife of a retired United Methodist Minister, serves as a community volunteer for a number of nonprofit organizations. She works in a Sacramento, California dining hall for the homeless, and helps with Emergency Services in Yolo County, in addition to volunteering for the Davis United Methodist Church. This essay originally appeared in The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown, ed. Rebecca Moore and Fielding M. McGehee, III (Lewiston NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1989).)

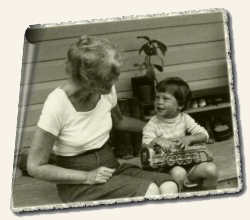

Our daughters, Carolyn and Annie, and grandchild Kimo were miracles of light and love and humor. Like meteors, their lives were brief and shining.

They died in Jonestown, Guyana on November 18, 1978, along with more than 900 other members of their community.

Carolyn first met Jim Jones in 1968 at Peoples Temple in Redwood Valley. My husband, John, our other two daughters, and I met Jim in Carolyn’s home a few months later. Twenty years have elapsed, and I have only now begun to arrange events in my mind and to assess my perception of the persona of Jim Jones. I shall leave to psychiatrists, sociologists and philosophers the characterization of charisma and its meaning. But I was extremely turned off by this dark-haired stranger with his rapid conversation and fast, giggly laugh. I like a man of good humor to chuckle, snort or guffaw.

The word “harbinger” comes to mind. The Harbinger of Death. And yet those who followed him — including a second daughter, Annie, who joined Peoples Temple a few years after Carolyn — felt that he brought new life to them. They were mesmerized by his personality and caught up in what can be described only as astoundingly solid social service projects.

Eventually our dog, Willy, also met Jim Jones. Willy had never bitten or snarled at anyone. An authentic product of the 1960s, Willy was a floppy-eared, large-footed, smiling fellow who chased butterflies and loved the world and its inhabitants. But he growled at Jim upon their first encounter.

If superstition and unease entered my consciousness when I met Jim, I would also have to admit that the old adage, “Hope springs eternal” competed with it. I told myself that some good things were happening in Peoples Temple, and that it would probably phase out in time as many movements do. But from Carolyn’s first descriptions of Peoples Temple, John and I were uneasily aware of what we felt were bizarre activities encouraged by Jim Jones. Here was a leader who was a combination of preacher, financier, political strategist and fraud. Anything could happen.

The followers of Jim Jones, on the other hand, were incredibly idealistic and creative. Peoples Temple had been conceived during the Kennedy/Vietnam era of concern for people of every race and condition. Temple members were deeply religious people in the sense that they were committed to caring for the poor, the disturbed, and the retarded of the land, as well as to changing political institutions that they might better serve the public.

Certainly our daughters entered the Temple with that commitment. My husband, John, is a minister in the United Methodist Church, and we raised our three children to understand the true meaning of compassion, sharing and human responsibility.

The members of Peoples Temple came from many backgrounds. Some were children of southern slaves, some were young adults from the upper-middle class community of Burlingame, California. There were chemists, accountants, mechanics, teachers, lawyers, nurses, carpenters, craftspeople, and artists, as well as ex-prisoners and recovering alcoholics and drug users. They represented a cross-section of the entire U.S. population.

Jonestown, Guyana was a magnificent venture! Set in a thousand acres where dense jungle had once stood, this unusual town had a library of several thousand books, a medical clinic, a dental facility, a nursery school with beautifully-crafted furniture and play equipment. Neat little white fences separated well-tended paths and gardens brimming with flowers and vegetables. Surrounding the settlement were fields of crops, fruit orchards, and a large animal farm. There was evidence of play and education, as well as hard work: Jonestown boasted a basketball team, a rock band, and evenings of laughter and song, in addition to schools offering classes for all ages. Recognizing that its existence was due in part to the graces of a foreign country, the community maintained contacts with the government of Guyana, as well as cultural and university leaders. It was to be a utopian community.

If the people of Jonestown had not had a crazed and power-hungry leader, the experiment might have worked. The tragedy is that an entire community died in response to the violence of a few in the bloody killings at Port Kaituma.

The first details in news bulletins from Jonestown were sparse. Following the reports of Congressman Leo Ryan’s assassination came rumors of 200 deaths in the settlement itself. John and I were worried, but hopeful, as fantasies of their survival ran through my mind. Of course our daughters, being of sound mind and practical sensibilities, were still alive. Perhaps Annie had led Kimo and a group of children through the jungle into Venezuela. What imagination I possessed! I went ahead with Thanksgiving plans at our Reno, Nevada home in a ritualistic manner, even as friends dropped by to express their concern. One friend who had experienced travail in her own life said, “I feel that your daughters are alive.” “Of course,” I told myself.

“Foolish woman,” I told myself later, forever floundering through life.

The truth is, I was all cried out — almost — when the news came. I began crying about six years before the final tragedy. Ours had been a close family, full of jokes and gifts and shared experiences. There was no alienation, even when Carolyn and Annie belonged to Peoples Temple. It was just that they were more separated from what had been and what was and what ordinarily would be. It was a sadness on our part, and a new and exciting adventure on their part.

They were always a part of us that neither time nor space could separate. Letters and calls arrived every two or three weeks. We wrote and sent gifts regularly as well. Still, after they left the U.S. for their jungle life, I told myself, “They’re never coming home again.” I tried to resist this insight into the future, and tried to focus on Annie’s gifts as a nurse and artist, and on Carolyn’s talents as the administrative assistant to the world and everything in it that needed organizing and fixing. Others tried to help me with that nagging feeling, too. When I shared my daughters’ descriptive letters with a friend, he remarked that of course they would return to the states one of these days.

Within a few days of the tragedy, we heard the news that Carolyn’s witty, vivacious friend Sharon Amos, with whom we’d corresponded, had slit the throats of her children and herself in the Temple’s Georgetown house. John and I fell sobbing into each other’s arms. This was reality. If Sharon had killed her own beautiful children, then the rest of it had to be true as well. Jonestown, and our daughters and grandson, were gone as well.

At the time, the event seemed to defy comprehension or satisfactory explanation. Nevertheless, the expressions of support and comfort from relatives, friends and even strangers were overwhelming. Catholic, Jewish, United Methodist, and other religious communities provided unending love and concern. The city of Reno seemed to go through the mourning process with us. People may not have understood the phenomenon of mass suicide at the time, but they offered us incredible understanding and comfort.

In the week following the tragedy, John had decided he would not preach the following Sunday. I’m not certain why I told him he had to speak, but he changed his mind. It was a magnificent sermon! Two years later, it was still surfacing in different places around the country, including a peace vigil at a nuclear missile site. It was a testimony of love for our family and the frailty of the human spirit.

I’ve carried my shattered psyche as we’ve moved from city to city since the tragedy of Jonestown, asking myself frequently, “Why, God?” as I dusted our family’s faces in their framed photos. At other times I’ve screamed mentally, shouted and railed against religious cults and charismatic leaders.

John is often asked to speak on the subject of cults and to take an active role in bereavement groups for parents of children who have died violent deaths. We also meet with people who are recovering from years spent in a religious cult. That experience has been fruitful, and they are adjusting to a fulfilling life.

Jonestown and Jim Jones are forever present in our lives. The words leap from newspapers and magazines in unrelated life-stories and incidents. For example: In January [1988], I was called for jury duty in the Yolo County courthouse near our home in Davis, California. There were about 60 of us, and I was the second person questioned by the two attorneys. I answered the usual questions about my work, my marital status, the number of children I had, and, of course, my belief in the jury system and my own ability to render an impartial verdict.

My answers were neither perfunctory nor flippant, although I felt that the lawyers preferred “yes” and “no” answers. At one point, I mentioned that my judgment was fair but not always perfect, and that I would not want to serve on a case involving a capital crime. That didn’t disqualify me, as the case was one of theft.

When they asked me the ages of my children, I said that one was 36. After a pause, I added, “Two are dead.” Both attorneys were silent for a minute, then accepted me as a juror. I had had other plans for the week, but understood the plans would have to change. This was going to take a few days.

During the lunch break at a small restaurant nearby, I happened to sit next to another potential juror. She was a jolly, garrulous person, full of stories and experiences. “I really enjoyed your answers to the lawyers’ questions,” she exclaimed. “‘Now there’s a person who would rather not serve on this jury,’ I told myself. I don’t think they’re going to retain you.”

“But I’ve been passed,” I told her.

“No,” she replied. “I doubt if they’ll keep you.”

We returned to the courtroom. It was exceedingly quiet. We jurors whispered to each other as though we were in church. The judge finally came into the courtroom, seated himself, looked up and said, “Is there a person in this courtroom whose daughters died in the Jonestown massacre?”

The silence in the room was thick. In a state of shock, I raised my hand.

“You’re dismissed,” the judge said.

That was the opportune moment for the drama of the day and a question on Jonestown’s relevance to the case, but I failed to seize it. Instead, I rose from my chair with as much dignity as I could muster and left the room. As I reached the corridor, the bailiff caught up with me and thanked me for coming.

Although I was in a state of shock, I chided myself for being a big sissy, and decided it wouldn’t prevent my driving home and preparing for the next emotional upheaval. I understood then, as I do now, that reminders will occur over and over in my life.

Four months later, I received another letter calling me for jury duty. That time, I marched into the office of jury selection and told the registrar of my previous encounter with the court. I then announced I did not intend to serve on a jury in Yolo County this year, next year, or ever.

For more than 30 years, John and I have been writing letters and demonstrating on behalf of peace and justice issues. Despite the wounds of personal tragedy, we have hoped our zeal would not be diminished. I did not noticeably change my activities following my daughters’ deaths, though I began to feel more compulsive about fulfilling the needs of others. Whether this could be termed the “spiritual imperative” or simply the process of middle age, I cannot say. Perhaps it’s a little of both. When I mentioned to a young college friend that I would like to do some writing, he replied, “Gee, you better do it soon. You could be run over by a truck at any time!”

The significance of relating to the dispossessed, the hungry, and the ill through the years has had intense meaning for me. I have worked part-time in a Catholic Worker dining room for poor and homeless people, and I am helping in a local emergency relief organization and a women’s rehabilitation cooperative.

The fourth-century desert fathers of whom Thomas Merton wrote admonished one not to seek the easy life, nor vainglory. If a wounded psyche brings on visions of spending one’s life as a Mother Teresa, it also enhances an enduring pursuit after pleasure and good times. In fact, I’ll accept as much vainglory and hilarity as I can possibly absorb. I voraciously consume good books (and bad books), good food, art, music, the company of our friends and relatives, the pleasure of our surviving daughter and her family, and the humorous, serious, wise and ridiculous experiences of life.

Before his death by execution, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote some final words to his family, the poignancy of which still speaks to me:

I should like to say something to help you in the time of separation that lies ahead… First, nothing can make up for the absence of someone whom we love. We must simply hold out and see it through. That sounds very hard at first, but at the same time, it is a great consolation, for the gap, as long as it remains unfilled, preserves the bonds between us. It is nonsense to say that God fills the gap: he does not fill it, but on the contrary, he keeps it empty and so helps us to keep alive our former communion with each other, even at the cost of pain.

Secondly: the dearer and richer our memories, the more difficult the separation. But gratitude changes the pangs of memory into a tranquil joy. The beauties of the past are borne, not as a thorn in the flesh, but as a precious gift in themselves.