(Rose Wunrow’s article about writing this paper is here.)

(Rose Wunrow’s article about writing this paper is here.)

The events at the agricultural project Jonestown on November 18, 1978 have been described in two different terms: as the “Jonestown suicides” and as the “Jonestown massacre.” Some argue that the deaths at Jonestown cannot be perceived as a massacre, as the majority of the people who died of cyanide poisoning had drunk the Kool-Aid and cyanide mixture voluntarily. Nonetheless, the mass suicides were decidedly a mass murder, enacted through the use of psychological exploitation instead of physical force. As the leader of the religious group Peoples Temple, Reverend Jim Jones was responsible for the psychological massacre of his followers because of the manipulative means he used to demoralize and control them.

* * * *

In order to understand the nature of Jones’ leadership over his followers, it is necessary to retrace the story of Peoples Temple to its very beginnings. The birth of the Temple is a largely inspirational story. In 1955, a 24-year-old reverend rented a small building in a racially-mixed section of Indianapolis. With a group of 20 followers, he founded a religious group called Wings of Deliverance, after leaving his position as reverend of the Laurel Street Tabernacle because of the congregation’s resistance to a racially-mixed church (Ksander). A year after its founding, Wings of Deliverance was renamed Peoples Temple. The Temple was known in Indianapolis for its social activism and for the services it provided for society’s disadvantaged; they opened a soup kitchen and an orphanage and provided services for the disabled (Ross, Rick). And Rev. Jim Jones himself served as a model for the Temple’s commitment to societal equality. In 1960, Jones and his wife adopted a black child. They were the first white couple in Indiana’s history to do so (Ksander).

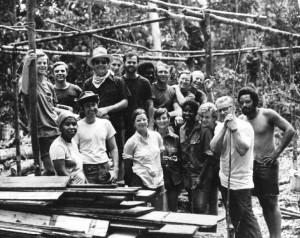

Yet that is not the part of the story for which Peoples Temple would be remembered. By the late 1970s, media reports were beginning to paint images of the Temple which were increasingly removed from the positive ones of its early days (Lindsey). These new images painted a picture of a religious group which was like a cult, whose members weren’t allowed to leave and were cut off from their families and the rest of society. In 1977, Rev. Jim Jones moved his congregation of several hundred followers from San Francisco to a remote agricultural project in Guyana called Jonestown. Allegations of tyranny and cruelty under Jones’ rule from relatives of Temple members prompted Congressman Leo Ryan and a group of journalists to travel to Jonestown to investigate; Ryan and several others were killed by a group of Jones’ followers when they tried to leave with Temple defectors (Ross). In the ensuing pandemonium, Jones said that, because of the murders, the Temple would be dissolved – a measure which Jones insisted needed to be prevented at all costs. The price named by Jones was everything that the Temple members had to offer. On November 18, 1978, 909 Temple members in Jonestown took cyanide mixed in Kool-Aid in what was the largest mass suicide in modern history.

* * * *

In order to understand the unconditional adulation of Jones which allowed him to manipulate his followers, it is necessary to look at Jones’ influence and appeal through the lens of the time period of the Temple’s formation. In the 1950s, American society was becoming increasingly turbulent in a variety of sectors. Joseph McCarthy’s provocative war against communism generated widespread fear in Americans of the threat of a Communist takeover – fear which was compounded by the possibility of a nuclear war with the Soviet Union. The civil rights movement was just getting on its feet after the ‘55 bus boycott. American youth were becoming increasingly disillusioned with their parents’ way of life. Out of the chaos created by these societal issues, Rev. Jim Jones emerged with somewhat revolutionary ideas which appealed to a wide range of disillusioned and disenfranchised Americans. Those who attended Temple services were drawn in by Jones’ passionate attacks on segregation and the “abuses, disgraces, and contradictions of American capitalism” (Jeffrey), as well as his dreams of a Utopian society in which all members were treated equally, no matter their stature in the hierarchy of society. Jones’ personal charisma and his mesmerizing power as an orator were also alluring and believable; he “had an intensity about him that made people believe anything he said” (Parrish). Jones used this intensity to increase his control over his followers. He urged Temple inductees to sell their belongings and turn their assets over to the Temple – an act which, in effect, was the first step towards putting Jones in a position of significant power (UPI). Temple membership soon grew from several hundred to approximately 20,000 at the Temple’s peak in San Francisco, where Jones relocated the Temple in 1971 (UPI). His congregation was “completely mixed, race, age, creed”– the composition of the Jonestown population was 75% black, 20% white, and 5% Asian, Hispanic, and Native American (O’Shea; Chidester). From an outside perspective, Peoples Temple presented an idealistic picture of a society which was unattainable in mainstream culture.

For a significant number of followers, Rev. Jim Jones provided guidance which they could find nowhere else in their lives. Many of his followers had been addicted to drugs prior to joining the Temple, or homeless, or escaping from abusive situations. Teri O’Shea (who defected from Jonestown three weeks before the massacre) had been 19 years old when her mother tried to strangle her with a dog chain. O’Shea had been hitchhiking to California when one of the people who gave her a ride told her about the Temple, a community where O’Shea would be unconditionally welcomed and protected. According to O’Shea, “I fell for it hook, line, and sinker” (O’Shea). For people like O’Shea, Peoples Temple appeared to be a safe haven where they could work on reshaping and rebuilding their lives. In his speeches, Jim Jones certainly promoted this image and his role as a crusader against injustice. He said at one Temple meeting,

I represent divine principle, total equality, a society where people own all things in common. Where there is no rich or poor. Where there are no races. Wherever there is [are] people struggling for justice and righteousness, there I am. And there I am involved. (Nelson).

Yet the leadership of Jim Jones was less that of a benevolent father figure than that of a dysfunctional manipulator bent on increasing his own power. While Jones’ public persona embraced equality and socialism, his relationship with his congregation displayed no such values. During the course of Peoples Temple, Jones worked to reshape the lives of his followers himself, by using increasingly harsh tactics which amplified the subservience of his followers until they were virtually stripped of free will.

Jones as a Messianic figure was an illusion that he embellished to openly justify his supremacy over his followers. He asked his followers to call him “Father” and used a variety of methods to prove to his congregation that he had divine powers. His methods included staging “fraudulent psychic-healing demonstrations using rotting animal organs as phony tumors; searching through members’ garbage for information to reveal in his fake psychic readings; drugging his followers to make it appear as though he were actually raising the dead” (Webb). The subsequent adulation of Jones by his supporters made Jones increasingly narcissistic; he claimed that he was the reincarnation of Lenin and Jesus Christ. Dr. Rebecca Moore, whose two sisters died at Jonestown, said, “He began by believing in his cause, but eventually ended up believing in himself” (Moore).

Jones used the unquestioning devotion of his followers to increase their dependence on him. He isolated them from anyone outside of the Temple. According to former Temple member Vernon Gosney, “Part of [Jones’] philosophy was that family relationships are sick and need to be broken down” (Ross, Rick). Jones worked on breaking down connections between Temple members as well; he rearranged marriages and insisted on celibacy – a rule which he himself did not follow, having numerous sexual liaisons with both men and women. Jones insisted that all men were gay and all women lesbian, and that he was the only true heterosexual (Kilduff). He further demoralized some of his followers by making them strip naked in public meetings and be subject to criticism from the rest of the congregation (Kilduff). These forms of degradation created a status quo within the Temple which was vastly different from that of the outside world. In the microcosmic world of the Temple, members were expected to relinquish their personal freedoms without question. Individuality was something to be suppressed. The perception of the congregation as a single entity was becoming increasingly predominant, even from the public perspective.

This conglomerated perception of the Temple was never more exemplified than by the role the congregation played in San Francisco politics. Former Temple member Tim Stoen said, “[Jones] was able to deliver what politicians want, which is power. And how do you get power? By votes. And how do you get votes? With people. Jim Jones could produce 3,000 people at a political event” (Ross, Rick). Temple followers all voted for candidates according to Jones’ preference. According to former Temple members, Jones “told [them] how to vote” (Crewsdon). After an election, Jones ordered his followers to show them their ballot stubs; if a follower didn’t vote, they were “pushed around, roughed up, physically abused” (Crewsdon). Yet the majority of Jones’ followers remained compliant. According to former Temple member Jeannie Mills, “We wanted to do what he told us” (Crewsdon). And because Jones’ orders went unchallenged in the Temple, he was able to guarantee politicians a significant number of votes – an ability which earned him friends in high places. In 1975, California Mayor George Moscone was elected with a margin of just 4,000 votes; soon afterwards, he made Jones chairman of the City Housing Authority, a position Jones held until his resignation in 1977 (Hatfield). California state assemblyman Willie Brown was also a staunch supporter of the Temple; he once introduced Jones at a dinner as “a combination of Martin Luther King, Angela Davis, Albert Einstein, and Chairman Mao” (Ross, Rick). The people in Peoples Temple – because they were so submissive and under Jones’ control – unanimously were used as an instrument with which Jones could increase his own sphere of influence in the world. The cost for Jones’ followers was to further lose their independence of thought and opinion, a human right embodied by the free election. Yet Jones’ influence in mainstream society at the expense of his followers was soon to be greatly reduced.

* * * *

The first public challenge to Jones’ leadership of the Temple came in 1972 – not from within the Temple, but from the media. In an eight-part series, reporter Les Kinsolving described allegations of beatings and shady financial dealings within the Temple, as well as the improbability of Jones’ “divine powers” (“Lester Kinsolving Series on Peoples Temple”). The San Francisco newspaper The Examiner only published four of the eight parts, after Temple members picketed outside of the newspaper’s offices and wrote letters of protest to the editor (“Lester Kinsolving Series on Peoples Temple”). The next challenge came in 1977 and carried far heavier implications. The magazine New West published a story based on interviews from ten Temple defectors. The article’s authors wrote, “Based on what these people told us, life inside Peoples Temple was a mixture of Spartan regimentation, fear and self-imposed humiliation” (Kilduff and Tracy). Former Temple member Elmer Mertle described a technique used by Jones called “catharsis,” a form of public humiliation. Mertle said in the article:

The first forms of punishment [in the Temple] were mental, where they would get up and totally disgrace and humiliate the person in front of the whole congregation. . . . Jim would then come over and put his arms around the person and say, ‘I realize that you went through a lot, but it was for the cause. Father loves you and you’re a stronger person now. I can trust you more now that you’ve gone through and accepted this discipline.’ (Kilduff and Tracy).

In reference to why the Mertle family stayed so long in the Temple, Mertle said, “We had nothing on the outside to get started in. We had given [the church] all our money. We had given all of our property. We had given up our jobs” (Kilduff and Tracy). The article’s publication was devastating to Jones and his popularity with the public. He traveled to Guyana immediately, where in 1974 he had sent several followers to lease over 3,800 of remote jungle terrain, and had already begun building the agricultural commune called Jonestown (Nelson). Two months later, almost a thousand followers went to join Jones in Guyana (Kilduff).

In Jonestown, Jones took his control to a new level, partly as a result of his own damaged ego and self-image. The man who had “loved being in the limelight” was, in Jonestown, suddenly exiled from the outside world and the sphere of influence he had held in it (Wagner-Wilson). According to Laura Johnston Kohl, who was buying supplies in Georgetown on the day of the massacre:

[In Guyana] he wielded more power over his congregation than he could have in the US. There was no one in Guyana – in Peoples Temple – who would stand up to him, or even get him to reflect on what he was doing, so he was unchecked. The quote ‘Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ exactly states what happened to him (Kohl).

Jones’ accelerated drug use also contributed to his increasing irrationality and fixation with maintaining control (Moore). His addiction, which had escalated from minor pharmaceutical usage earlier in his life, was only made apparent to most of his followers after the move to Jonestown, particularly because of the change in his style as an orator. His “trademark passionate delivery gave way to blind fury and incredible rage” (Ross, Rick). His speeches were increasingly fatalistic and began putting the idea of suicide into his followers’ minds: “I said, life is a fucking disease. It’s worse than cancer. It’s a disease. And there’s only one cure for the sonofabitchin’ disease. That’s death” (Ross, Rick). Over the loudspeaker in Jonestown – which he used to preach to his congregation for hours every day – Jones’ speech was becoming increasingly slurred, and, as observed by many Temple members, “he stumbled over his words, which was not a common thing with Jim” (Webb). The illusion of stability which Jones had maintained early on was completely destroyed. In the days before Congressman Leo Ryan was killed, Jones was unable to conceal his addiction from the group of journalists and Ryan’s aides who visited Peoples Temple. San Francisco reporter Ron Javers, who was wounded during the shooting that killed Ryan, recorded his observations at the time: “Jones has struck us as a madman. We watched him as he kept taking pills until he seemed dazed by them. He listed a whole catalogue of diseases he said were afflicting him, starting with cancer” (UPI). The leader who had helped many of his followers get off of drugs was, by the end of Jonestown, using “uppers to help him stay awake, and then used downers to get to sleep” (Moore). According to Moore, “His ‘super-human’ abilities to stay awake clearly were the result of drugs” (Moore). An autopsy on Jones’ body after the massacre revealed a level of barbiturate pentobarbital (a prescription drug used as a short-term treatment for insomnia) which would have killed an ordinary person, signifying that Jones had been using the drug for a considerable amount of time (Find-A-Grave). Drug use, compounded by pressure from several other sources – including a custody battle over one of Jones’ illegitimate children – made Jones turn on the community with more intensity.

Increasingly paranoid that his followers would turn against him, Jones went to greater lengths to assert his control by constantly testing his followers’ loyalty. In staged suicide rehearsals called “white nights,” Temple members were told to drink red liquid which may have contained poison, so that Jones could see how many of his followers would follow his orders unhesitatingly (Ross, Rick). After distributing cups of the liquid among his followers, Jones would say, “In forty minutes, you will all be dead. Now empty your glasses” (Brinton). The frequent “white nights” have been cited in the argument that the Jonestown deaths were suicides, and not a massacre. According to Moore:

Arguments for murder, however, ignore the fundamental fact that the threat of suicide was an ever-present reality for those in Peoples Temple. They discussed it, rehearsed it, and accepted it with little dissent. This made suicide not just an option, but rather an inevitability. (Moore)

Yet the constant suicide rehearsals actually reinforce the argument that the events at Jonestown were a massacre; the rehearsals were simply another component of Jones’ mind control methods. By making suicide an “ever-present reality,” Jones trivialized its gravity with theatrics until the act of committing suicide became almost automatic for his followers. The suicide rehearsals, and Jones’ orchestration of them, actually make it clearer than ever that the Jonestown deaths were a massacre: their frequency emphasizes the extent to which Jones had pre-planned the massacre and accustomed his followers to the idea of its necessity.

However, some argue that the existence of the “white nights” is the greatest indicator that what occurred at Jonestown was a mass suicide (Ross, Devin). Those who stayed despite the implicit possibility of suicide were “making a conscious decision to accept Jones’ leadership,” even to the point that they would willingly commit suicide at his direction (Ross, Devin). It is true that a number of Jones’ followers willingly remained in Jonestown for a variety of reasons, including ongoing belief in the Temple’s values and a sense of family within the Jonestown community (Wagner-Wilson). Yet by that point, many Temple members were so broken down, both physically and psychologically, that they weren’t in any position to contemplate leaving or to resist even the idea of suicide. Deborah Blakey, whose 1978 affidavit would raise awareness of the deteriorating situation at Jonestown, said of the congregation’s reaction to “white nights,” “We all went through it without a protest. We were exhausted. We couldn’t react to anything” (Brinton). And because the condition of Jones’ followers was the product of Jones’ manipulative control over them, the Temple members cannot be held accountable for their compliancy during the “white nights.”

The state of Jones’ followers at this point in time resulted from a variety of mind control methods (the “white night” being one of them) that Jones used to break down his followers’ psyches. These techniques used by Jones were remarkably similar to those used in government-sponsored behavior modification experiments performed in the same era as Jonestown.

One such research experiment was Project MK-ULTRA. Developed during the Cold War and the Korean War, Project MK-ULTRA was a covert CIA operation experimenting with behavior modification, targeted at offsetting “communist mind control efforts and developing their own to aid in the espionage wars” (Porter). Some (including former Ryan aide Joe Holsinger) even question whether the formation of Jonestown was a CIA experiment, because of the striking parallels between techniques used in Jonestown and MK-ULTRA – electric shock, drugs, sleep deprivation, and beatings, among other means (AP). MK-ULTRA was terminated in the 1970s after the Washington Post published an exposé describing its methods (Porter). Another similar experiment exemplified the destructive effect that mind control techniques can have on the human psyche. Theodore Kaczynski was a volunteer in a CIA-sponsored mind control project at Harvard in the 1950s. The instability which led Kaczynski (also known as the “Unabomber”) to enact a 20-year bombing spree has been attributed to the effects of the psychological abuse he suffered during the Harvard project (Cockburn).

Evidence suggests that Jones consciously used mind control techniques from his own research to increase his power. Stanford University psychology professor Philip G. Zimbardo believed that Jones was influenced in particular by George Orwell, whose futuristic book 1984 explores social psychology and the effects of mind control on the masses (Dittmann). Techniques which Jones borrowed from Orwell included the idea of “big brother is watching you” and self-incrimination (Dittmann). Yet the reason why Jones wanted to have uncontestable control over his followers is debated. One suggested motive was that Jones, for whatever reason, had always planned the death of his followers, and that his power would ensure its inevitability. According to O’Shea, Jones had once proposed setting fire to the Temple building in San Francisco while his followers were locked inside (O’Shea); he had also discussed intentionally crashing a plane full of Temple members (O’Shea). Whether these early suggestions had any backbone behind them is questionable. However, the deaths of the Temple members in Jonestown suggest that Jones may have increased his control for such a purpose. This is particularly supported by the range of techniques that Jones used to subjugate his followers while in Jonestown.

* * * *

The different means that Jones used to control his followers in Jonestown varied greatly. The amount of physical punishment in Jonestown was “numbing,” according to Gosney (Ross, Rick). One common instrument of punishment was a coffin-sized box kept several feet underground; people put in the box would be talked to incessantly and reprimanded for their wrong-doings by someone above ground (O’Shea). Not even children were safe from unusually cruel punishment; those who wet themselves were shocked with electric cattle prods (Brinton). Jones also ensured that his followers received no news from the outside world; the single radio in the compound was monitored at all times, and letters going in and out of Jonestown were censored. Over the compound’s loudspeaker, Jones would sometimes report events which followers had no way of verifying, ranging from warnings of an imminent nuclear holocaust to stories of the Ku Klux Klan “marching through the streets of American cities” (Nelson).

Jones also guaranteed that his followers were completely isolated from each other by creating a system encouraging people to inform on each others’ actions, which generated suspicion and paranoia between his followers. If one follower openly expressed a desire to leave the Temple, those who heard him had to report him immediately, as the follower may have been speaking under Jones’ orders as a way of trapping them into agreement (O’Shea). Children were encouraged to report on their parents. Jones further magnified his followers’ paranoia by pretending that he could read their minds. When Temple members died, Jones announced that he had killed them because he had read their thoughts and they had been thinking of leaving (O’Shea). Temple followers were now expected to regulate their thoughts according to Jones’ expectations, as well as other forms of independent expression. Their ability to speak freely had already been largely quashed by Jones, as exemplified by an encounter between Jonestown members and people from the outside world. Some weeks before the massacre, a US embassy official interviewed almost 50 Jonestown members out of Jones’ earshot – members whose relatives in the United States had expressed concern that they were being abused (Mears). Yet none of those interviewed said they wanted to leave. According to Blakey in her affidavit, “The members appear to speak freely to American representatives, but in fact they are drilled thoroughly prior to each visit on what questions to expect and how to respond” (Mears). Because of the lack of free speech, the first open indication of how many people wanted to leave the Temple came with Ryan’s visit to Jonestown, when he was approached by numerous Temple members who asked to leave with Ryan (Ross, Rick). Yet, prior to Ryan’s visit, the feeling of total isolation and fear of punishment ensured that Temple members suppressed any thoughts they may have had about leaving.

Sleep deprivation was perhaps the most effective weapon which Jones used to break down his followers’ psychologies. According to O’Shea, “One time Jim said to me… ‘Let’s keep them poor and tired, because if they’re poor they can’t escape and if they’re tired they can’t make plans’” (O’Shea). Followers were made to feel guilty if they slept for longer than several hours a night; they were expected to work six days a week and were perpetually exhausted. According to research, people who are sleep deprived “do not have the speed or creative abilities to cope with making quick but logical decisions, nor do they have the ability to implement them well” (Ledoux). The effect of sleep deprivation on the psyches of Jones’ followers no doubt significantly increased their willingness to take the cyanide at the time of the massacre.

In the last several months of the Temple, Jones lessened the amount of physical punishment in favor of another, more invasive form of control. He began to use prescription drugs as another mind control technique. When the compound was inspected after the massacre, a staggering amount of anti-depressants, downers, and pharmaceuticals was discovered; there were enough doses in Jonestown to have treated every Temple follower “hundreds of times” (King). Towards the end of the Temple, potential defectors and “troublemakers” had been placed in an “extended-care unit,” where they were given drugs like Thorazine – used normally as a treatment for severe neuropsychiatric conditions – until they “lost their desire to leave the commune” (King). According to medical officials, one side effect of the drugs Jones used was “suicidal tendencies” (King). Jones obtained these drugs by having Temple members go to the doctor complaining of particular symptoms; when the doctor gave them prescriptions, they would then turn over the medication to Jones (King). Jones, in turn, used them to manipulate his followers’ behavior in a variety of ways. The Temple security guards who killed Ryan were “probably drugged,” according to former Temple member Gerald Parks (Webb). Jones would feed his followers drugs in grilled cheese sandwiches, and, according to Parks, the four security guards “had cheese sandwiches that day” (Webb). Jones’ use of heavy prescription drugs on people whose only problem was their desire to leave Jonestown was another way of maintaining uncontestable control – when under drug-induced stupors, followers were even more acquiescent to Jones’ demands.

Natural factors also catalyzed Jones’ power by weakening the morale of the community. While Jonestown had been established as an agricultural commune, it was never agriculturally self-sustaining (Hatfield). Heavy rainfall had washed away much of the fertile soil from the site of the commune, and the wood from the trees surrounding them was so hard that they had to import planks to build structures (Brinton). In addition to crop failures, two-thirds of the Jonestown population had been weakened by tropical diseases to which they had no built-in immunity (Hatfield). The community was discouraged. Temple member Vernon Gosney found it “hard to explain the state of mind people were in. We were broken down” (Ross, Rick). Leaving was not even a remote option for the majority of Jones’ followers. O’Shea, who left Jonestown with a group assigned to deal with Jones’ legal complications in the US, was one of the Temple followers who managed to break free of the Temple; once in the US, she defected, changed her name, and went into hiding until the FBI located her after the massacre. She said of her escape, “You had to really be ready to say, ‘I don’t care if I die, I don’t want to live another day like this’” (O’Shea).

* * * *

When Deborah Blakey defected from the Temple in May 1978 and released an affidavit urging the US government to intervene to protect the endangered lives of the people in Jonestown, the Justice Department did not know how they could investigate without interfering with the Temple’s freedom of religion (Mears). They were unaware that there was no freedom of any sort left in Jonestown. The department also believed that “allegations of brainwashing and other thought control techniques would not suffice to prosecute cultists as kidnappers” (Mears). In 1978, concerns raised by a group of relatives whose family members were in Jonestown drove Congressman Leo Ryan to investigate the situation in Guyana himself. He took with him to Jonestown a group of aides, journalists, and concerned relatives.

Ryan’s first impressions of the community were positive and admiring. As his aide Jackie Speier said, “How could you not be impressed that out of the jungles of Guyana, they had carved out a community? They had crops growing. They had cabins. They had a little medical clinic, a little daycare area” (Nelson). Yet after the welcoming ceremony for Ryan, reporters were slipped two notes which said, “Help us get out of Jonestown.” One woman approached Speier and said, “I’m being held prisoner here, I want to go home” (Nelson). In the end, a group of 15 Temple defectors accompanied Ryan and his contingent to the Port Kaituma airstrip, where two planes were waiting to return to the States (Staebroek News). One of the defectors, who had been planted there, opened fire on the passengers inside of one of the planes as Temple members fired on Ryan’s contingent and the defectors outside of the second plane (Staebroek News). Five were killed and ten seriously wounded (Staebroek News).

Back at the compound, Jones had been seriously shaken by the defections. According to O’Shea, “If he had let those people go, that would’ve been OK…but he saw every defection as a huge attack on his person” (O’Shea). Jones called an emergency meeting and told his followers, “The congressman is dead! You think they’re going to allow us to get by with this? You must be insane. They’ll torture some of our children here. They’ll torture our people…We can not have this!” (Nelson) He continued, “If we can’t live in peace, then let’s die in peace” (Nelson). Jones began distributing Kool-Aid mixed with tranquilizers and cyanide in syringes, then brought out a vat full of the poison for the adults to drink from. Those who resisted were forced to drink, injected with cyanide, or shot by Jones’ security guards (Staebroek News).

Within moments, the “revolutionary suicide” had been carried out in its entirety. An anonymous note found in the compound read, “Collect all the tapes, all the writing, all the history. The story of this movement, this action, must be examined over and over. We did not want this kind of ending. We wanted to live, to shine, to bring light to a world that is dying for a little bit of love” (Nelson).

* * * *

It is not possible to generalize about a group of people as large as the group that died in Jonestown. Yet the previously-discussed factors affected everyone at Jonestown, and the different effects of those factors had demoralized Jones’ followers enough so that many of them complied unresistingly with Jones’ final demand. Perhaps the same philosophy which drove O’Shea to escape drove those at Jonestown to drink the cyanide-laced Kool-Aid: perhaps they simply didn’t “want to live another day like this.” Yet the fact that what happened was done willingly by the majority of Jones’ followers does in no way indicate that the deaths were a mass suicide. Even the fact that some may have wanted to die at the end implies that Jones psychologically massacred his followers by leaving them no options and no way out. Jones’ brutal orchestration of the suicides themselves also increased the volition of some of his followers. Jones ordered that the children be poisoned first; parents gave cyanide to babies by squirting it down their throats with syringes (Ross). By organizing the suicides in this way, Jones ensured that he severed the last ties which could have made some of his followers resist taking the poison – the bonds between parents and their children. This first step of the massacre expedited the second step: Jones first psychologically massacred the parents by making them watch their children die, and then pushed them to their own deaths.

The people at Jonestown had been driven past the breaking point. They had been beaten, sleep deprived, degraded, separated from their families, and stripped of all personal freedoms. In the end, even the rigid structure of their lives at Jonestown had spiraled out of control, and they were pushed down a one-way street by Jones – a one-way street which ended in “revolutionary suicide” (Staebroek News). The Jonestown massacre was the product of years of disintegration within Peoples Temple, disintegration which can be attributed in its entirety to the increasing egomania and irrationality of Jim Jones. The unconditional faith that Jones’ followers had placed in him allowed them to be victimized by his obsession with manipulation and mind control. And because of Jones’ tyranny, Peoples Temple was never able to achieve the Utopian society in Jonestown which Jones had promised. Leslie Wagner-Wilson, who escaped through the jungle with several others on the day of the massacre, said, “I say that the people who thought they were making a difference were only pawns in a game, in which they paid the ultimate price – with their and their loved ones’ life. They compromised everything.” She added, “We all have choices, and we must never place everything at the feet of a man. Only God deserves that” (Wagner-Wilson).

Those who survived Jonestown look back with mixed emotions on their time in Peoples Temple and the rule of Jim Jones. In light of Jones’ widespread deception of his followers, some former Temple members question whether his motives and professed beliefs were ever genuine. Kohl said of Jones in the beginning of his leadership, “I think that Jim learned the Bible thoroughly and then was surprised by the power he was able to develop around it. The same with his healings, and his message of racial equality, and utopianism. I think he…was delighted that these heartfelt beliefs would be a calling for so many followers. Then, he began to make good use of the messages” (Kohl). However, O’Shea called Jones’ commitment to racial equality “a way for poor black people to give up their Social Security checks” (O’Shea). Attitudes towards Jones himself vary. While O’Shea described him as a “sociopath,” Stephen Jones, Jones’ only biological son with his wife Marceline, said of his father, “There’s no denying there was a warm heart inside a really sick being. Most of the accounts you hear and see about Jonestown don’t depict that” (Ross, Rick). Wagner-Wilson said of Jones, “Personally, I do not put complete blame on Jim Jones because my mother had a choice to leave or stay while in the States, and she chose to stay. Why, I will never know, as she and my family perished in Jonestown” (Wagner-Wilson). While attitudes towards Jones vary, former Temple members’ memories of the community are fairly cohesive. In an interview with CNN, Kohl said, “The thing that I think is the most understated was that we really did have a community that, had Jim Jones been forced aside…would make a successful community living there with people of all different races and backgrounds, which really would have been a promised land or heaven on Earth” (Ross, Rick). O’Shea agreed, “The community itself was a lot of really well-intentioned people” (O’Shea). It had been the community, in part, which had prevented Temple members from defecting when they still had the option. Gosney said that, though Jones’ rule was tyrannical, “Still, Peoples Temple was a family, if a punishing family. It was an intense experience of coming together and living communally with people from all different backgrounds. It satisfied this basic desire I had to connect with all humanity” (Ross, Rick). Yet because of Jones’ manipulative rule, the community was unable to reach its full potential and make the changes it so desired.

The harsh conditions of Jonestown and the effects of various punishments on Jones’ followers make Jonestown a tragic example of the power of mind control and the vulnerability of the human psyche to manipulation. Because Jones was responsible for enforcing these manipulative conditions, the deaths of the 913 deceived Peoples Temple members cannot be remembered as the “Jonestown suicides.” Jim Jones’ demoralization of his followers, and their inability to escape from the iron vice of his control, make the “Jonestown massacre” the only accurate title for the events at Jonestown on November 18, 1978.

Works Cited

AP. “Papers: Jim Jones Used Sex to Rule, Blackmail Followers.” The Evening Independent [St. Petersburg]. 24 Nov. 1978. Print.

Brinton, Maurice. “Suicide for Socialism? Brinton on the Jonestown Massacre, 1978.” Libcom.org. 25 July 2005.

Chidester, David. Salvation and Suicide. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press. 2003. Print.

Cockburn, Alexander. “‘Unabomber’ Ted Kaczynski Was CIA Mind Control Subject!” The Revelation @ The Forbidden Knowledge.Com. 9 July 1999.

Crewsdon, John M. “Followers Say Jim Jones Directed Voting Frauds.” New York Times. 17 Dec. 1978. Print.

Dittmann, Melissa. “Lessons from Jonestown.” American Psychological Association (APA). Nov. 2003.

“Find A Grave – Millions of Cemetery Records and Online Memorials.” Find A Grave – Millions of Cemetery Records. Jan. 2001. http://www.findagrave.com/.

Haney, Elissa. “The Jonestown Massacre: The Ministry of Terror.” Infoplease. 2007.

Hatfield, Larry D. “Utopian Nightmare.” SFGate. 13 Nov. 2008.

Jeffrey, Jason. “Who Was Jim Jones?” New Dawn Magazine. Jan. 1995.

Kilduff, Marshall. “The Trouble Starts: Drugs, Sex, Beatings, Defections.” The Modesto Bee. 5 Dec. 1978. Print.

Kilduff, Marshall, and Phil Tracy. “Inside Peoples Temple.” New West. 1 Aug. 1977: 30-38. Print.

King, Peter. “How Jones Used Drugs.” San Francisco Examiner. 28 Dec. 1978. Print.

Kohl, Laura Johnston. E-mail interview. 16 Apr. 2011.

Ksander, Yael. “Jim Jones | Moment of Indiana History – Indiana Public Media.” Indiana Public Media. 25 June 2007.

Ledoux, Sarah. “The Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Brain and Behavior.” Serendip (2001).

“Lester Kinsolving Series on Peoples Temple.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. 14 Sept. 2009.

Lindsey, Robert. “Enigma of Jim Jones: A ‘Saint’ Becomes a Devil.” The Day [Eastern Connecticut]. 29 Nov. 1978, 126th Ed, sec 1:1+. Print.

Mears, Walter R. “Is Religion Too Free?” The Milwaukee Journal. 30 Nov. 1978. Print.

Moore, Rebecca. E-mail interview. 18 Apr. 2011.

Moore, Rebecca. “The Sacrament of Suicide.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. 16 Nov. 2008.

Nelson, Stanley, Producer, Director. Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple. WGBH American Experience. PBS Home Video, 2007. Transcript.

O’Shea, Teri Buford. Telephone interview. 16 Apr. 2011.

Parrish, Tina. “Leadership Styles: Martin Luther King vs. Jim Jones.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. 25 Jan. 2009.

Porter, Thomas. “History of MK-ULTRA. CIA Program on Mind Control.” Deep Black Magic. 1995.

Ross, Devin. “Culture, Charisma, and Peoples Temple.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. 16 Nov. 2008.

Ross, Rick. Jonestown: Jim Jones and the People’s Temple. The Rick Ross Institute, 1996-2008.

Staebroek News. “Jonestown 20 Years Later.” 22 Nov. 1998.

UPI. “Personality Spotlight: Rev. Jim Jones, Founder of the People’s Temple.” Florence Times. 23 Nov. 1978. Print.

Webb, Alvin B. “Jonestown Survivors Describe Their Escape.” The Bryan Times. 24 Nov. 1978. Print.

Wagner-Wilson, Leslie. E-mail interview. 16 Apr. 2011.