Photo obtained through Freedom of Information Act

Richard David Tropp was the firstborn son of Russian Jewish parents. When I met Dick in Berkeley in 1967, he was living at a large and legendary artists’ collective on Woolsey Street. Already an accomplished cellist, he was taking lessons on the sarod from Ali Akbar Khan at a school in Terra Linda, in Marin County. He had attended college at the University of Rochester in New York, and worked as a teaching assistant at Fisk University. He was deeply committed to racial justice, and to transforming society. We teamed up and moved to Northern California to join or start a commune. We found a little house at the end of a gravel road, high on a hill overlooking Highway 101, in a tiny town (just a crossroads, really) called Redwood Valley. The cabin we rented was about one-half mile, as the crow flies, from the Peoples Temple.

Dick’s plan was to work for a friend’s brother, cutting jade in Ukiah. The jade was mined in the high, remote mountains north of Covelo, home of the Round Valley Indian Reservation and the nearest civilized outpost for the miners. They hauled the jade in a huge old truck down from the mountains to the shop in Ukiah where the boulders were cut by slow-moving automatic saws into large slabs. All day, we cut the slabs of jade on huge circular diamond-tooth saw blades cooled by an oil bath, into small rectangles to be sold in rock shops or supplied to jewelers for further finishing. At night, we compared our thighs, which were a sea of red pimples from the oil bath. The job petered out after about six months, and Dick looked for other work, first serving as a counselor in a home for troubled teens, and then as a census worker. It was during his census rounds in May of 1970 that he first met Jim Jones.

Dick was lanky, brilliant, sensitive and intense, and I will not pretend to know his mind. I was awed by Dick’s grasp of reality, political understanding, and vision. He was always gentle and kind toward others. His brooding absorption might have been taken for aloofness, unless you spoke to him and he turned to you meekly attentive and helpful, self-effacing in his humor, the soul of humility. We meant to help build the new society we all thought, in 1968, was waiting only for us to create it.

In the late 60s religious affiliations were just another husk of the old society to be shed in preparation for the Aquarian Age. But I remember that what attracted me to Dick was his character; and the fact that we had similar goals. It’s hard to remember now just how foreign it would have been for either of us then to identify with or practice the religion of Judaism or Christianity, although Dick was very Jewish in his manner and appearance, his voice at times nasal and touched with a New Yorker’s cynicism. Our friends were musicians and intellectuals, with whom he jammed, and discussed starting a commune. One of them had heard of the Temple, which had recently relocated to California from Indiana, and had attended a service. He mentioned it to us, and the next thing I knew, we were going. I was affected by the service, but not enough to want to go back. “He implies he’s Jesus, this guy is weird,” I protested to Dick. Dick said nothing, and the next Sunday, he got up and went without me.

So I went back to the Temple with Dick that Sunday night. During the service, Jan Wilsey, a young Native American from the Pomo tribe in Middletown, stood up and sang Buffy Sainte-Marie’s “My County Tis of Thy People You’re Dying,” a wrenching recount of the tragedies suffered by her people. Well, I had loved that song, and Buffy Sainte-Marie, and it just swept me away. I fell like a tree. There was no more hesitation, People’s Temple had claimed me.

I can see how Dick found the Temple irresistible. The challenge had gone out to whites in the late 60s, through the Black Panther Party and then the Weathermen, to choose a side, either with the oppressed or the oppressor. Though we might have been “dropping out” to found the new society, we were still comfortably removed from the struggle and heavily dependent, especially in that conservative rural community, on being as white as we were (despite our ardent lip service to racial justice). I think once Dick saw the interracial character of the congregation, and heard the revolutionary rhetoric of Jim Jones, he felt he had no choice but to stay. The Temple offered a better opportunity to live our commitment to social justice than anything we could manage on our own.

As we became more involved in the Temple, we found everything that had bound us to each other either fading, or proscribed by the new orthodoxy. To begin with, relationships were selfish and not to be indulged in at a time of revolution. Flirtation, or entertaining thoughts of mutual attraction, exclusivity and favoritism were referred to as “compensating.” Devoted members didn’t do it as it was considered selfish, a display of insecurity, and a serious weakness, potentially dangerous to the collective interest. What mutual attraction we shared could not withstand this pressure, and our relationship became platonic, then seemed to wither away entirely as we moved into different communes.

Harriett, Dick’s sister, came for a visit a year or so after we joined, and stayed. Dick and Harriett had a brother, Martin Tropp, who never came to the Temple, and died in 2006. Dick worked as a teacher at Santa Rosa Junior College during most of his time at the Temple. He wrote many of the articles in the Peoples Forum, the free newspaper that was published by the Temple in the mid-70’s.

One day, when the move to Guyana was imminent, Dick stopped me in an upstairs hallway at the San Francisco Temple, and took me aside for a private conversation. He had made me a beneficiary of his retirement account at Santa Rosa Junior College, and he wanted me to know that if anything happened to him, I would be getting his retirement for the years he had worked as a teacher. I remember my glib response: “I’ll just give it to the church,” I said, mindless of the risk he had taken, both to do that in the first place, and then to tell me about it. We mused briefly about our likely future – me, throwing out some bravado-laced comment about how we’d “all go together”; he, demurring to say, “there are other ways to solve things besides ‘damn the torpedoes.’” On that note, we parted, but I never forgot that glimpse into his true feelings about the futility of suicide as a political statement. What else did he doubt? I promptly forgot what he had told me about the retirement money and it was almost ten years after he died in Jonestown that the State Employees Retirement Fund found me, remarried, with the name I have now, to give me the benefit Dick had set aside.

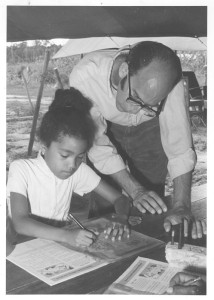

In Jonestown, Dick was in charge of the school. He worked hard to make it great, and to bring visitors from other organizations and countries to Jonestown. In summer 1978, he started writing to me often with urgent requests that I write this or that religious magazine or organization, telling them about Jonestown and asking them to visit, but I never did. My work in the San Francisco Temple’s in-house Publications Department as part of a small support staff here in the U.S. was technical and low-profile. I had no aptitude for public relations or desire to deal with “outsiders.” I wonder to this day, if I had done what he asked, whether he might have made contact with someone who could have saved him, and all the rest of them.

Charles Garry, on his return to San Francisco, brought us survivors who had been living in the San Francisco Temple into his office one at a time, for serious questioning. He had barely escaped with his life and wasn’t in the mood for any bullshit. He told me then that he had heard Dick arguing long and passionately with Jim Jones on the morning of November 18th before the meeting was called in the pavilion. He said, “I think they must have killed Dick or drugged him or something, to be able to go through with it.” Rereading the few examples of Dick’s writings from Jonestown that are available at this site, including his Dramatic Reading, it is hard to know if Charles Garry was right, that Dick could not have been in the pavilion. The “Last Words” sound like his – especially the parenthetical insert referring readers to the “Teachers’ Center” – the writer seemed to realize that the horrific act he was struggling to explain would be totally incomprehensible to those left behind. In the end, failing to make a clear case for their action, in despair he said, “it doesn’t matter any more… I am ready to die now.”

Whether Dick was killed or just overruled may never be known. The fact that he resisted as he did makes him one of the few, like Christine Miller, who confronted Jim Jones that day and tried their best to stop the ending for which Jim had so elaborately prepared us.

I have clung to what I know of Dick’s resistance and my guilt at not trying to save him until they have outweighed everything else I remember of us. In his Last Words, I see only the underlying despair and frustration in trying to express why they were dying and knowing that if he couldn’t define it, there was little hope that I, you or anyone else would understand. This article ends, unresolved, unfinished, like Dick’s life.

Redemption? Resolution? I hope to see it in my lifetime. I hope for Dick (and all of Them) to be redeemed by the principle they lived for – socialism – being resurrected and reclaimed as a force for good. Resolution will come when all the books have been opened, including the one that elucidates who and what exactly the perp – Jim Jones – was hoping to accomplish.

(Kathy Barbour [Tropp] joined Peoples Temple in 1970 with her companion, Richard Tropp, and was living in the San Francisco Temple on November 18, 1978. Her other articles in this edition are The Names and What have we learned in 32 years? Her complete collection of writings for this site can be found here.)