Though I’d read it about in books, Jonestown didn’t become real to me until years later, when an acquaintance gave me a first-hand account of the tragedy’s aftermath.

Though I’d read it about in books, Jonestown didn’t become real to me until years later, when an acquaintance gave me a first-hand account of the tragedy’s aftermath.

I was a reporter, and he was a community activist. During one of my interviews with him, we got slightly off-topic, and he told me how, decades earlier, his family’s funeral home had been involved with embalming bodies from Jonestown, and trying to make it possible for relatives to identify their loved ones. To that end, the funeral home had agreed to handle inquiries made through a toll-free phone number set up by the federal government. But only a handful of people ever called – and none followed through – so the dead went to a mass grave, alone and unclaimed. Uneasily, I wondered who these people had been, and why no one had come for them.

I wanted to find out more, but harried workdays blended one into the next, and then, strangely, as time rolled by, I resisted being reminded. A few months ago, when I accidentally channel-surfed across MSNBC’s “Witness to Jonestown,” I clicked away almost immediately. But after a few minutes, I decided to go back and watch. I was finally ready to learn more. More than that, I was ready to do more.

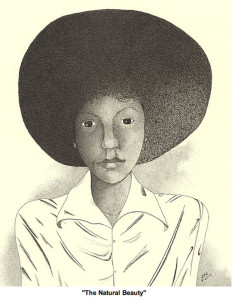

Since I’ve always been bothered by the fact that the victims were buried without personalized markers, it seemed important to concentrate on the people as individuals – on their faces. I drew a portrait, and then a second, and soon I found myself immersed in a series of drawings. I usually draw for fun, and I’ve never been very good at portraits, but for this project I was determined to try.

As I worked on this, my friends and acquaintances noticed how much time I was investing in my new project. Some shared my interest, to a degree, while others were bemused by it, and a few were critical. At times I’ve found myself hotly defending those Peoples Temple members who went to Guyana.

More than one person has asked me why Jonestown resonates for me. It has taken a while to figure out how to answer.

Part of the reason, I think, is that I have always hated to see people judged unfairly.

Besides that, in some ways Jonestown reminds me of two of my cousins. When I was about 10, I was told that one cousin, Andrew, had joined a cult. From his immediate family’s perspective, Andrew basically disappeared, though he showed up to borrow money from time to time. Meanwhile, his brother, Scott, was handsome, successful, and thoughtful. Everyone loved Scott, and though my family lived too far away for us kids to be very close, I always felt that Scott deserved the adoration. The last time I saw him, he went out of his way to make me feel comfortable at a big party, while Andrew, practically a stranger at that point, lurked in a corner. When I approached Andrew, he was nice enough, though he sharply criticized the adults for drinking. To my 13-year-old eyes, he was an enigma. To at least some of the other guests, I know he was a nuisance.

When Scott died unexpectedly before his 30th birthday, everyone grieved, rightly, yet I was chilled to hear more than one person say, “Why couldn’t it have been Andrew?”

As I look at my drawings now, I sometimes think of my cousins. It’s true that one seemed easier to understand, yet I don’t see how anyone could pick one over the other.

To me, each person’s life has a value that can’t be quantified, no matter what their choices are, and no matter whether their choices result in tangible benefits to their families or anyone else.

I’ve read a lot about the idealism and social activism of the Peoples Temple community, and as much as I respect that, I don’t think those qualities should be used to defend them. They shouldn’t have to be defended. Their lives were their own, to spend as they wished, regardless of whether they wanted to fight racism, build a better world, or do nothing.

As I’ve tried to create images of a few of these people, that’s how I think of them, not as activists or social pioneers, but simply as people. When they died, the world lost something, but I tend to think of their loss – the loss of days and weeks and years that were theirs and theirs alone.

(Sasha Sark has also written three articles – and illustrated them with her art – on her blogspot. Her email address is here.)