(Chris Knight-Griffin is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His other article in this year’s edition is Modernity and the Old Believers: Jonestown was not an analogue. His complete collection of writings for this site may be found here. He may be reached at jonestownresearch@hotmail.com.)

(Chris Knight-Griffin is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His other article in this year’s edition is Modernity and the Old Believers: Jonestown was not an analogue. His complete collection of writings for this site may be found here. He may be reached at jonestownresearch@hotmail.com.)

On October 28, 1947, when Jim Jones was sixteen years old, the film Nightmare Alley made its debut. Produced in the heyday of the film noir genre, Nightmare Alley is prime example of a dark and criminal narrative that was meant to disturb the audience and instill a sense of angst. It may not be the quintessential shadowy drama, although it does contain a lot of the telltale disorientating mise-en-scène (theatrical staging, in this case, designed to confuse) of the era. Films of this mode – “genre” may not be apt in its classification – often contained violence, paranoia and “as Robert Porfirio suggests, with existential issues such as futility of individual action: the alienation, loneliness and isolation of the individual in industrialized mass society” (Belton 2005, 230).

How does this film fit into Jonestown/Peoples Temple narrative? To start, one assumption has been that Jim Jones actually saw Nightmare Alley. In addition, it is further assumed that Jones modeled himself after the main character played by Tyrone Power. Even though these assumptions cannot be confirmed, the belief of those closest to Jones suggests that this supposition has solid grounding. Some points presented here, I will concede, are purely speculative on my part, and the reader will have to decide for himself or herself as to their validity. Moreover, some evidence is anecdotal and open to challenge. As with most narratives, the case presented here in support of the assertion that Jim Jones was influenced by the film Nightmare Alley is based on a primary source, particularly and interview with Michael Cartmell who graciously donated his time and energy to this project.

The Trifecta of Politics

Nightmare Alley is the first film in a trifecta that sets the stage – or the pulpit – for Jim Jones’ ministry. Even though Jones never mentioned this film, he did acknowledge on numerous occasions that the two others – Z (1969) and Parallax View (1974) – had enormous influence on him. The latter two confirmed his perception of a hostile and deceitful government and reinforce his own ideas of repression and paranoia; they are not so entwined in his actions, as they are in his thought processes. The only question remaining on the latter films is, is art-imitating life, or is life imitating art?

It is this first film, however, that shifts Jones’ path from simple minister to incorporate one of “showman.” Nightmare Alley has many parallels with from Jones’ early years, and the similarities between Jones and film’s main character, Stanton “Stan” Carlisle (Tyrone Power) become difficult to dismiss. Stan is a loner who desperately tries to find his own voice and whose path is destined to end in ruin over his failure to remember the past, the warning hanging over the pavilion at Jonestown amidst the carnage of the murder/suicides in Guyana.

Nightmare Alley: The Movie

The premise of the film is that of a drifter, Stan, who works a travelling carnival show as a “barker” only to be mesmerized by the carnival’s geek (one who performs odd or vile acts). The geek, it is later learned, is really a down-and-out alcoholic who is paid in liquor or moonshine with the added benefit of “a dry place to sleep it off” at night. Stan’s dream, however, is to become famous. He starts to look for an act he can take outside the carnival to achieve this goal, and in doing so, he befriends, and nearly seduces, Zeena Krumbein (Joan Blondell), a mentalist working the carnival with her husband Pete Krumbein (Ian Keith). Stan soon learns that Zeena and her husband used to perform a mentalism act using an advanced code on Vaudeville. Already perfected, the act is, according to Zeena, worth a sum equal to a full “retirement.”

Stan understands that and presses Zeena to teach him the code. The situation gets desperate for Zeena when her husband dies from drinking wood alcohol – a death she had foretold in a reading of Tarot cards – and Stan takes Pete’s place in the act. Regrettably, Stan is the one who inadvertently caused Pete’s death, a point that becomes crucial later in the film as the source for Stan’s guilt.

Stan grew up in an orphanage under strict religious supervision, without a father figure in his life. It is this religious training that Stan uses to great effect in dealing with pious “judges” by feigning belief and being “being saved.” This implies a long history of troublemaking and evading punishment. Moreover, Stan has learned how to “read” people, or rather, he has learned to tell people what they want to hear. He shows this as he dazzles the town marshal who is threatening to shut down the carnival by “reading” him much to the bemusement of the carnival owner and the admiration of Zeena. He is quick to use religion as the basis for his manipulation and personal gain, since it the most effective system of deception.

Once Stan has learned the code from Zeena, he leaves with his younger love interest, Molly (Colleen Gray). However, because of some perceived impropriety between Molly and Stan, the pair is forced to marry. Even though the marriage could be read as punishment for their indiscretions, Stan turns it into part of the act.

Stan and Molly go on to make it in the big time, until they defraud one too many believers, namely a local wealthy socialite and her skeptical partner. Stan has beguiled Addie Peabody (Julia Dean) and realizes that he could make all the money he needs from her. He acquires $150,000 from her to help build “a tabernacle,” but it is not enough. The irony in the story is that as he gets collecting almost enough money to complete his project, he himself is swindled by a female con artist, Dr. Lillith Ritter (Helen Walker). Put simply, the con is conned. Forced to leave town, Stan disappears onto the trains as an anonymous hobo, only to emerge on the carnival circuit as a drunk looking for work. The story eventually returns to its beginnings, as Stan becomes what he pitied at the outset: a carnival geek.

Jim Jones

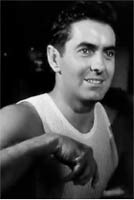

Did Jim Jones see Nightmare Alley? Unfortunately, we may never have a definitive answer. However, former Temple member Michael Cartmell described him as a “movie hound” (Cartmell 2009). Moreover, there are many similarities between the lead character and Jones, not the least of which is that the young Jones may have thought himself at least as striking as Tyrone Power, with the same jet-black hair and the debonair, if not slightly gruff, demeanor.

There are more substantive similarities. Both men – the real Jim Jones and the fictional Stan – had lonely, harsh childhoods in the film; both were ostensibly abandoned by their fathers; and both grew up to become street-savvy. Moreover, Power’s character in the film considered the fundamentalist religion he experienced in childhood as a tool to garner respect from those in authority, a tool Jones would later use quite effectively. Like Power’s character, Jones displayed a strong yearning for success and of wanting to be respected. In reality and on the silver screen, Stan/Jim viewed those who did not respect him or follow his every wish and command as traitors and enemies.

Like Stan in the film, Jones collected a lot of money during his life, yet he rarely spent it. The reason for this frugality may also come from the plot of Nightmare Alley. The main character’s only expense is self-promotion. Stan did not buy a lot of expensive gifts, cars, jewelry or any other status symbol, but rather used his wealth to buy access and the power that it held. Money was not the goal, but a means to acquire power.

Another similarity is that of Stan’s wife, Molly. Could Jim Jones have married out of convenience as well? He met Marceline Baldwin during the summer of 1946, and married her in 1948; Nightmare Alley was released in the interim. Marceline was from a politically-connected family, and the union would have been Jim’s first step up in the world. Marceline characterized the early years of their marriage as “lacking any genuine affection,” only to have love bloom later (Cartmell 2009). It is fair to say that Jim’s actions, like the character in the film, were calculated, and that those around them could not see the endgame. Both Jim and Stan used people – including their wives – and no one tried to stop them until it was too late.

As an additional comparison of note, Jim may have picked up the usefulness of combining two distinct professions—preacher and huckster. In the film, Stan is referred to as a huckster that talks like a preacher. How different is Stan’s mentalism in the film from Jim Jones’ faith healing and prophesy statements? The parallels are striking, as is the use of “cold reading” of having someone work the crowd for information and secretly feed it to the mentalist/faith healer. In the book The Faith Healers, James (The Amazing) Randi exposed the techniques used by one faith healer, Peter Popoff, who would send out confederates into crowd to relay whatever information they could gather back to him; in turn, he presented the divinely received knowledge to the audience at large and the mark in particular.

The film presents just such an act before Jim Jones perfected his own performance. Certainly it would have sparked his interest in the techniques used by professional mentalists and led him to incorporate them into his preaching.

I contend that Jim Jones not only saw Nightmare Alley, I believe he modeled himself after Stan, the film’s protagonist. The release of the film coincided with Jim’s impressionable teenage years, it offers a character Jim could identify with, both physically and substantively, and it presents two major themes which would weave throughout in Jones’ life: religion and cold reading (mentalism). Such coincidences are just too pervasive to be dismissed.

Bibliography

Belton, John. American Cinema American Culture. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Cartmell, Michael. Personal Correspondence via email. February 2, 2009.

Randi, James. The Faith Healers. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 1989.