On November 18, 1978, a Saturday, I was sitting in my Manhattan apartment a half-mile from the NBC studios wondering why the men I worked for hadn’t asked me to be in the newsroom when Congressman Leo Ryan entered Jonestown. News president Les Crystal and “Nightly News” executive producer Joe Angotti had hired my source, Gordon Lindsay, a freelance journalist whom I had met the previous May through my California cameraman. Lindsay was assigned to brief reporter Don Harris, the California reporter who’d replaced me on my own story. Anger overcame me again when I remembered being told that October day that a California crew was going to Jonestown with the Ryan party.

Tears came out of nowhere. I brushed them away, ashamed that I was so helpless and could do nothing about what they had done to me. Rape: I felt violated. The most important investigative story of my life, and here I was sitting in my living room watching traffic go by from my window, because the men I worked for decided they wanted a man – a team player they were comfortable with – instead of a woman on the story that I found, investigated, and shot on Peoples Temple in Guyana. I was ashamed that I still felt like a victim. Powerless. But I was.

Self-doubts crept in again. Didn’t they think I was tough enough to go to Jonestown? I had just aired a powerful series in June on “Nightly News,” then anchored by John Chancellor, on the Synanon cult. Pulling it together had been a grueling ordeal that almost cost me and my crew our lives.

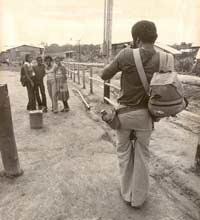

Cameraman Mark Allan, soundman Don Miller, and I had heard the sound first – the rhythmic beat of distant drums. It was 8 a.m. on a warm day in early May. I was planning a series on the Synanon organization, and this was our first day in the field. The Marshall-Petaluma road, an hour and a half north of San Francisco in Marin Country, was deserted. Rustling fields of rye hid whatever was coming toward us.

Mark, my favorite West Coast freelance cameraman, first told me about the Synanon cult led by Chuck Dederich in March of ’78. I had a tough time getting the story okayed by NBC News executives because Synanon was now a non-profit organization trying to get approved by the I.R.S. as a “new religion.” Joe Angotti was nervous about going after so-called “new religions” for First Amendment reasons. And the organization was litigious, in the midst of lawsuits with ABC and Time Magazine, which called it a “kookie cult.”

But more important, Angotti didn’t want to make waves because NBC was in transition. A new controversial corporate president had just been named. Fred Silverman, the creator of the popular Charlie’s Angels show – “The man with the golden gut,” as he was known – was an entertainer. He couldn’t care less about news, especially news that might bring trouble. Silverman was known for kicking elevators, temper tantrums, and firing people on a whim. His big broom was poised to sweep out the old NBC crowd – the “newsies” – and replace them with his own gang of hip young people from CBS and ABC, where he also had been corporate president. Silverman was on a roll, and Angotti didn’t want to get in Fred’s line of fire.

Even before Silverman’s arrival, Angotti anticipated lawsuits with Synanon, Scientology, the Moonies, the Children of God and Peoples Temple. The Temple’s tactics of intimidation and threats of litigation worked locally in California and virtually shut down media investigations on the West Coast. The Reverend Jim Jones, leader of Peoples Temple, was becoming a powerful man in San Francisco politics and could bring in votes for politicians. First Lady Rosalynn Carter allowed herself to pose and socialize with Jones at a political event that received national coverage and wrote him a short note on White House stationery regarding his views on Cuba. She suggested he speak with the evangelist Ruth Carter Stapleton, President Carter’s sister.

Now Synanon, which had a media strategy relationship with Peoples Temple, was on the warpath with Time magazine and an ABC affiliate in San Francisco. The group had been emboldened by a victory against the Hearst Corporation, which settled a lawsuit with them for $2.6 million. My timing for a high-profile investigative news series about destructive cults couldn’t have been worse.

Angotti, who later became a news consultant, and his close friend, Les M. Crystal, who was NBC’s new young news president and is now at the helm of Lehrer Productions at Public Television, wanted to keep their heads down. (Insiders said Crystal’s middle initial stood for “marshmallow.”) Also quaking with fear about losing his job was Cory Dunham, the head of the legal department. So here I was in California doing a very dangerous story with a nervous, unsupportive news management and a frightened legal department. I tried to block out the corporate politics and concentrate on my investigation of Synanon and Peoples Temple, and was idealistic enough to believe we were still in the business of public service, providing viewers with information they needed to know.

Ironically, Synanon started out doing the same type of good work as had Peoples Temple. Synanon founder Chuck Dederich made the cover of Life magazine for rehabilitating “dope fiends” and “drunks,” as he called them. He had been an alcoholic for many years and bragged that he started Synanon with his first $35 unemployment check. (Many of his so-called “tough love” therapy techniques are still being used in drug treatment programs.) But then, very gradually, the organization evolved into the cult of Chuck Dederich, the man, just as Peoples Temple became synonymous with the Rev. Jim Jones.

Synanon became controversial, secretive, and dangerous. Farmers and ranchers in Point Reyes, California, where Synanon was buying up property, lived in fear of what they perceived was a growing menace. Farm animals and pets began turning up dead, butchered and mutilated in what appeared to be satanic rituals. The talk was that Dederich had paid off the local sheriff to look the other way. Two Synanon members were deputized into the department.

Mark brought the van to a stop as the sound of the drums became louder. He looked over at me expectantly. Don, the soundman, a chain smoker, lit another cigarette nervously as he put a wireless mike under my jacket and tested his shotgun microphone that would catch ambient sound. We all left the van and waited on the empty road.

I didn’t see anything, but the drumbeat was getting closer. We heard barking dogs and stared at the fields of rye waiting for Synanon to make its appearance. Then we saw them – about 75 men, women and children with shaved heads and wearing overalls. Four German shepherd dogs strained at their leashes. Some people were beating long, narrow, small-headed drums with their hands. From a distance they looked like an army of ants on the move. They were carrying signs: “Entertainers go home.”

One young child had a dead chicken on a stick – his vision of the symbolic NBC peacock. A young man with dead eyes who moved like a robot carried a sign that said “APRL.” Later I learned that APRL stood for Alliance for the Protection of Religious Liberty, an organization of the most powerful cults, including Scientology, that was effectively silencing the media from coast to coast.

Mark never stopped staring into his viewfinder as he selectively taped the fields of rye, the empty road, and the approach of the menacing crowd. Don pointed his shotgun mike in the direction of the sounds. I flicked on my wireless. Suddenly, a person wearing a gorilla suit appeared out of nowhere and soundlessly jumped up and down. I saw that some of the skinheads were carrying rifles over their shoulders. Others had what appeared to be pistols in holsters at their waists. No one said a word. Mark captured the scene.

Finally, two men with shaved heads of medium height approached me and asked what I was doing. “None of your business,” I answered. They accused me of trespassing. I responded that we were on public property. I then asked if NBC News could have an interview with someone in charge, preferably with Chuck Dederich, if possible. They snickered, turned their backs on us, and left.

The rest of the group stood in silence waiting for instructions on what to do. We thought that was it for the day and started packing up our gear. Then Mark pointed to the new arrivals of big trucks. “Trouble,” he said, “we’re not done yet. He started rolling tape on the trucks. Four of them converged on the van and surrounded us. Synanon members parked the trucks to block our exit and raised the trucks’ hoods.

“There must be a Bermuda Triangle here,” mocked a Synanon member, “because our engines gave out.”

Again, the group of skinheads, ranging from children to adults in their forties, circled us without speaking. I tried to interview some of them, but word was passed from one Synanon member to another: “Don’t talk to them.”

After a half-hour of this silent encounter, we escaped by driving through a muddy pasture. Meanwhile, a rancher Alvin Gambonini, who had seen the blockade building up from his farmhouse and been severely beaten by Synanon a few months earlier, called the sheriff’s office. A local paper, The Point Reyes Light, sent its news editor, Keith Ervin, who arrived just behind the deputies to meet with us on the road at the end of the field. He photographed me and the crew filing a police report to take to his editors, Dave and Cathy Mitchell. Mark taped the event for our series and – to be sure – for NBC lawyers in case we were accused of provocation.

While this was going on, more people with shaved heads kept appearing out of the fields of rye. Synanon brought out over a hundred reinforcements to chant protests about news media coverage. The noisy protest was still under way when we arrived at The Light’s office. I interviewed Dave and Cathy Mitchell, then called Joe Angotti in New York and told him what happened. I asked for permission to hire a chopper for the next day to photograph the sprawling Synanon properties from the air. There was a long pause followed by a barely audible, “I’ll get back to you.”

I thought the show’s budget was on his mind with the new executives in place. “I’ll have a story for you tomorrow about what happened after we get the aerials, Joe.”

He said something like, “We’ll talk about it tomorrow,” and abruptly hung up.

What I didn’t know until later was that Angotti immediately called the legal department and briefed them about what had happened. Ordinarily, we’d only call in lawyers if there were legal questions in a script that we were unsure about. What I did realize as I hung up the phone was that Angotti never asked if we were okay.

The crew and I walked outside. To our surprise, the street was deserted. We drove down the road to where it all began. Don stopped the van and he and Mark got out. They began rolling again but all we could see was empty rye grass moving gracefully in the wind.

Dave Mitchell, who had been trying to get law enforcement and the public to take Synanon seriously, tipped off the San Francisco papers and the wire services about NBC being detained by Synanon. I had messages from the local San Francisco newspapers and the Associated Press and United Press International when I returned to my hotel. The newspapers ran articles the next day. The wire services ran a bulletin that night. But NBC “Nightly News” didn’t even mention the encounter.

Back at the bureau that evening, Angotti left a message that we could hire a chopper. The next morning, Mark, Don, and I drove to the airport and hopped aboard. Mark shot footage out the window as we made the half-hour helicopter trip to Point Reyes and the Walker Creek Ranch. As we headed north and approached the Synanon compound, people started running out and pointing up at us. Mark told the pilot to descend so we could get some faces on camera with our long lens.

We heard it before we saw it. Rifles. Pistol shots. The pilot ascended quickly and we continued photographing the scene. I didn’t expect that they would actually shoot at us. The crew and I were shaken, but no one showed it. Afterwards, Mark, Don, and I stared at each other. Synanon physically detained a network television crew. And shot at them. What next?

I was on an adrenaline high by the time I reached the San Francisco bureau. I called Angotti, who was as laconic as he had been the day before. “Give me 1:30. It’s a heavy news day. If we don’t use it tonight, you can use the footage in the series.”

“Use it in my series?” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. A camera crew detained by a bizarre cult brandishing guns and the next day shooting at us from the ground. The incident might not even make the show, although it was national news on the wire services.

What I later learned from a disgruntled news lawyer who left the network was that Synanon’s legal department had already called NBC News’ legal department. Fearing legal reprisal from them, and more important, the wrath of Fred Silverman, the ten thousand-pound gorilla now running a once-great network, the home of Huntley and Brinkley, NBC caved in to cult pressure.

No story ran that night on “Nightly News.” The footage later would appear in my series on Synanon that aired June 12, 13 and 14, with a fourth part later that month. That series unleashed a chain of events that ultimately led to the spiking in October of my series about the Unification Church, Scientology, Children of God, and Peoples Temple. The Peoples Temple series was ready to air six weeks before the Jonestown massacre that claimed 918 lives, including about 300 children, three newsmen, and congressman Leo Ryan.

But by this time NBC executives were frightened. There had been death threats as well as legal threats to NBC. A lawyer in California investigating Synanon was almost killed by a rattlesnake bite. The snake was put in his mailbox by Synanon members. In New York, Synanon got into Fred Silverman’s building in New York. He feared for his family. I was followed home from work and picketed. My desk at NBC was broken into and a notebook of addresses was stolen. The RCA building was picketed by about 50 cultists, chanting and carrying signs. I thought it went with the territory. The lawyers watching these incidents in the lobby at 30 Rockefeller Center didn’t appear to share my view of “territory.”

I made it clear to management that my series on the destructive cults, which management reluctantly approved after the Synanon series aired, would have Peoples Temple as the centerpiece. In October, when the work was done, I stressed that we air the series quickly. It would show the need for government protection of the Ryan party – that for everyone’s safety we had a responsibility to run this story before they left California for Guyana. Jim Jones, the leader of Peoples Temple, had been practicing suicide drills and was a known drug addict. He had nothing to lose if he was exposed so violence, and mass suicide was a strong possibility. Angotti had watered down my Synanon series before it aired, and now he looked at me as if I was just another hysterical woman going through her period.

No one else going with Congressman Ryan thought that Jonestown was anything but another tough story. Jones might be a madman, but kill a congressman? Ironically, the journalists thought they’d be safe because Leo Ryan was leading the group. Congressman Ryan thought he was safe because he had the journalists and a NBC network television crew with him, with a seasoned reporter who had covered Vietnam and looked and acted as tough as Clint Eastwood.

What I learned much later from my former boss, Bill Wheatley, then senior producer of “Nightly News,” was that “Clint” was full of himself and didn’t take criticism or editorial changes without a fight. Wheatley questioned his news judgment and considered him a loose cannon. Nevertheless, Harris was a man. And in 1978, there were no female investigative reporters at the networks, much less women who expected to cover dangerous stories with men in the jungle. Women did fluffy, soft features or consumer stories. They weren’t in network newsrooms except as secretaries.

I had no allies there. I didn’t fit in with them, and the women shut me out. To them I was an overeducated outsider whom their bosses tolerated. A token. Who did she think she was? It didn’t matter that I had already won an Emmy for a series on cocaine as well as other awards, had two years of print experience with a Gannett newspaper, a Master’s Degree in English, and two books to my credit while working at CBS answering audience mail letters. Audience mail. Writing form letters to viewers. That’s what I had to do to get in the door at CBS.

It was Wheatley, seven years my junior and without the middle-age man’s prejudice against women in the newsroom, who gave me my chance to work on “Nightly News.” I came up with original investigative stories that he noticed, but received no praise from the establishment men who ran the program. I was a non-person. A woman. Invisible. These men weren’t comfortable with working women, a new breed, and ignored me.

It was so bad then that when two of my main sources on the Synanon cult series passed through New York – their print work had been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for local reporting on Synanon – I was not invited to their meeting with management and anchorman John Chancellor. It wasn’t until later that I learned that Dave Mitchell and cult psychologist Richard Ofshe were even there. They told me they had asked where I was and was told I was out of town. I had been a phone call away.

I had grown accustomed to not being invited to story meetings, even meetings about my own stories. Wheatley was given the embarrassing job of reporting back on a need-to-know basis. I felt humiliated and left out, but back then I accepted it as “normal.” It was. I was reminded of it every day.

In mid-October, Angotti and Crystal spiked my story on the destructive cults without explanation. Shooting stopped. My California replacements were given the assignment. Except for Don Harris reading my copy of the Gordon Lindsay report for research purposes, I was ignored.

Harris didn’t return my phone calls about that report, which was the story proposal that sold the story back in June. And he never asked to see the footage I already shot or my rough cut. The Peoples Temple series was put on the back burner, I was told by a sympathetic news lawyer.

I was speechless. I was so shocked that I didn’t get angry – as a man would, I guess – and demand an explanation. I had been conditioned to be well behaved, know my place, and be grateful that I was working on “NBC Nightly News.” Nevertheless, I took the bold step of tipping off a friend at The New York Post. It published an item that led NBC to issue a press release that said NBC News was “not caving in to pressure from the cults” and that the decision to take me off the Jonestown story was strictly “an editorial decision.” I was off the most important story I had ever worked on before or since.

Access to all information was cut off. Corporate president Fred Silverman made that very clear to the legal and news department heads. I found that out by accident at a local NBC news hangout called Hurley’s. Soon after I was taken off the story, I was having a drink at the old oak bar. Silverman’s second in command, Paul Klein, who had come over with him from CBS, sat down next to me.

Not knowing who I was, only that I was young and attractive, he laughingly told me the story about some “crazy woman” in the news division who was driving his boss Fred crazy. He shared how Synanon was menacing Fred and his family in New York and even got inside his apartment building and spoke to him on the intercom. The harassment and legal intimidation that Synanon was famous for at Time Magazine and at ABC – and now happening at NBC – was reported in the national press.

I remember slamming my drink glass down on Hurley’s bar and introducing myself to Paul Klein as “that crazy lady.” He shrugged his shoulders and went back to his martini.

* * * * *

I believe the tragic event at Jonestown could have been avoided if NBC News had not caved in to cult and corporate legal pressure and death threats, done its job as a news organization, and informed the public about what was happening to American citizens in Guyana, most of whom were being held there against their will in the jungle by a drug-crazed madman.

What I also knew was known by the American Embassy in Guyana, the State Department in Washington, the Justice Department in Washington, the Bureau of Alcohol and Tobacco and Firearms, the CIA, and California law enforcement agencies. It also was known by Peoples Temple defectors, concerned relatives of Temple members, and my main sources, freelance journalist Gordon Lindsay and Steven Katsaris, unofficial leader of the Concerned Relatives group and a former Greek Orthodox priest, who was in close contact with the State Department and the other state and Federal organizations.

Despite what everyone knew, a lone congressman was allowed to embark on a “fact-finding mission” to what so many people knew was a dangerous steamy jungle prison run by a man obsessed by betrayal, paranoia, control, and death.

Why Congressman Leo Ryan was allowed to go to Jonestown without protection remains as much of a question now as it did then. For thirty years the government has kept its secrets well-classified, to be processed for possible release beginning in 2010. NBC News archivists told me it has only 18 minutes of the almost three hours of that unforgettable tape I screened in November 1978. Where has all that tape gone? Documentary filmmakers who worked on 30th anniversary programs last year called me to find out if there was more footage. I was dumbfounded, astonished at the news. Irreplaceable historical footage, gone? Missing? A man died getting that tape. I saw it all and edited stories for “Nightly News.”

And what the tape revealed was an irresponsible, poorly informed reporter breaking news rules, and ordering his cameraman to tape people who didn’t want to be taped. The reporter, Don Harris – despite being warned – conducted a 25 minute “take no prisoners” interview with a drug-addled madman. Only one question remains of that interview now. Soon after that interview all but two of the NBC crew were dead. Cameraman Bob Brown, reporter Harris, and Congressman Ryan died first on the crude runway at Port Kaituma seven miles from Jonestown. Later that night, over 900 others would die. Some died by their own hand, but this was no mass suicide. Babies and reluctant adults were injected with deadly poison. Two people – including Jones – were found shot to death.

Because decomposition of the bodies had set in quickly as they lay in the hot sun for four days, because only a handful of autopsies were performed, and because the bodies that were autopsied had already been embalmed, it was virtually impossible to say how most people died.

Almost a thousand Americans died in the jungle more than thirty years ago, and we know little more now than we did then. Why? Did they die in vain, their assassins here in this country very much alive and never punished? No public hearing was held where questions could be asked, answers demanded and culpability assigned by government officials. More than thirty years later the most important documents remain classified by the Justice Department, and the videotapes turned over to the agency remain unaccounted for. Why?

Have we become so cynical that the deaths of almost 1000 Americans who followed their leader to what they believed was a new world where everyone would be equal doesn’t matter, and what the perpetrators did wasn’t so bad after all? After all, everyone lies. Watergate. Iraq. Who cares about Jonestown now, the number-one story of 1978? Today, it’s ancient history. And most of the victims were poor blacks and whites.

It’s been ancient history for a long time. In March 1981, syndicated columnist Jack Anderson got on to information about my suppressed investigation and interviewed people I had worked with, but too much time had elapsed. And nothing came of it. And last year, when two cable networks did their obligatory 30th anniversary coverage of the tragedy, their producers made their obligatory contact with me. They bled me dry for information about what was on the hours of tape I screened, more of which are now mostly missing. As for my personal experience with cult intimidation of the media and its effect on news decisions regarding my series on the cults and particularly information the interviews on Jonestown, they weren’t interested in that. Neither were they interested in anything I had to say about the actual disappearance of the tapes, network irresponsibility, or government classification of thousands of documents. That wasn’t the story these producers wanted to tell. And many of the news executives who made those bad decisions because of intimidation are still around. The Jonestown tragedy continues.

But NBC News was the first to lose its way. It could have made a difference by exposing what was happening in Jonestown in time for it not to happen. The story was “in the can” and ready to go.

Finally, where are those historical tapes that a NBC cameraman died to get to inform the public of a news event he could have avoided taping by hiding, as many did on the airstrip that day? They survived. Bob Brown didn’t let cynicism blur his passion to record the truth and expose what he saw.

The afternoon dragged through that Saturday in November 1978. My phone was silent. I wanted to call Wheatley to find out what was going on. Gordon Lindsay had called me the night before from Georgetown, Guyana and said the Ryan party finally had permission to enter Jonestown. They were going in. (Ironically, Lindsay survived because Jim Jones detested him for his investigation and wouldn’t let him in.) A good man, Lindsay. A Brit, he had a different attitude toward women in journalism. And he knew I had put my life on the line doing the Synanon series. It was he who kept me informed about what was happening because I took his work seriously, went with it and advanced it.

The phone rang. I ran to my desk to answer it. It was my cameraman Mark Allan, who had introduced me to Gordon and worked with me on the Synanon series when staff crews refused the job. “Thank God you’re alive,” he said. “Turn on your radio. There’s a bulletin that congressman Ryan, some journalists, defectors, and concerned relatives were murdered by Jim Jones’ people on the airstrip near Jonestown.”

I got off the phone, grabbed a cab and went to 30 Rock. The newsroom was in turmoil. Wire service machines were spitting out stories and updates. Phones were ringing. Chaos. Angotti came over to me and said with hatred, “Those people weren’t worth it, Pat.”

I was speechless. I wanted to say, “Is that because most of them are black and poor?” But I was in shock and didn’t have the presence of mind to say it. I ran into Crystal’s office in the newsroom, out of control. “Les, if we did what we were supposed to do, none of this would have happened.”

He stood up. “Never say that again,” he said. “Never.” Then he turned his back on me.

I was shouting now. “Do you realize that everyone in the Peoples Temple is probably dying right now?” He didn’t answer.

What Jim Jones called the “White Night” was happening as I stood there looking at Les Crystal’s back. Babies were being injected with poison. Older people were being killed. Some were taking the poison voluntarily, blindly following their demented leader to the end. As a result, 918 people died that day. This wasn’t mass suicide and certainly not “revolutionary suicide,” Jim Jones’s grandiose name for it. It was murder. It was a massacre.

“That could have been me,” I thought, feeling my armpits sweating and my face flushing. I had this vision of myself wounded on the muddy Port Kaituma airstrip, watching a man with a gun coming toward me in slow motion. The gun was held execution style.

I knew I could have made a difference, had my series aired when it should have a month before the massacre. The government would have had to take action. Congressman Ryan, NBC’s Don Harris, his cameraman Bob Brown, who died still taping the carnage at the airport, photographer Gregory Robinson of The San Francisco Examiner, defector Patricia Parks. Dead. So many wounded. A bloodbath that didn’t have to happen if the State Department and intelligence agencies had done their jobs, and had provided them government protection. That series would have pressured them into affording them that much. Months before the Ryan party went down, so many in our government knew what it would be facing. They were no better than the armed assassins on the flatbed truck. But why?

Dave Mitchell of The Point Reyes Light – who, along with his wife Cathy, won a Pulitzer Prize for their local reporting on Synanon – believes the federal government has kept the Jonestown material classified because it “greased the skids” to bring the controversial cult to Guyana and convinced officials there that there was no security risk. Was Leo Ryan’s elderly mother, Autumn Ryan, right? “The State Department and the CIA let my son go down there to die, and we’ll never get to the bottom of it,” she said. It was her son who tried to restrict illegal activities of the Central Intelligence Agency in foreign countries by co-authoring a controversial piece of legislation, the Hughes-Ryan Act.

This is a story that still needs to be told for several reasons. One is the matter of accountability for 918 needless deaths and the dereliction of duty by the U.S. government and intelligence agencies. Another is specifically journalistic accountability – decisions were made for reasons other than the public interest and ethics, and those decisions cost many people their lives. Additionally, at a time when the media is being criticized for missing the truth about weapons of mass destruction and the war in Iraq, telling this story is not only a way to come clean but a cautionary tale for all news organizations.

(A previous article by Pat Lynch appears here.)