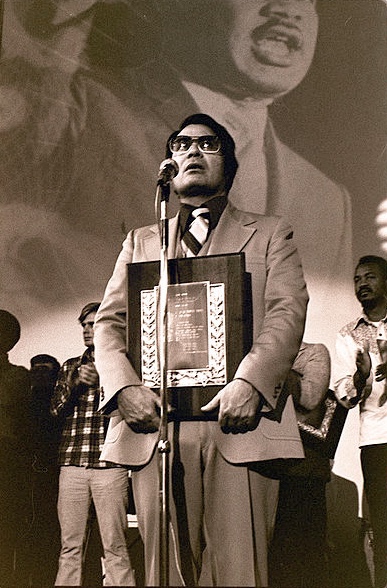

Photo by Nancy Wong

During the 1960’s a messianic preacher moved his religious operation from the Midwest to a small town in Northern California. Building the congregation using the rhetoric of racial equality, Peoples Temple became a strong, active church. The founder, Jim Jones, a former door-to-door monkey salesman, encouraged his followers to create a racially diverse church. Members claimed that the Peoples Temple was a way for racial groups to practice “intimate diversity.”[1] Using the rhetoric of the Civil Rights Movement, Jim Jones forged an identity for the church that was rooted in leftist politics and racial equality.

Recently there has been an upsurge in scholarship and artistic portrayal of the Temple and its nebulous and intractable legacy. Some conservative pundits claim that civil rights scholars have ignored this episode of American history because it complicates the traditional apologetic stance of historians towards radical groups in the civil rights Movement, such as the Black Panthers.[2] In this essay I will analyze the coverage of Peoples Temple in scholarship, and try to explain what role the rhetoric of the Civil Rights Movement that Jim Jones and other members of the Temple played in building a following. Did Jones cynically exploit current events? Or was Peoples Temple an honest movement that went astray? Though much has been written about Jonestown and the cult’s demise, the role of the rhetoric of the Civil Rights Movement has not been studied thoroughly. Did Jonestown, as pundits like Emmet Trell argue, represent the failure of racial politics that played a role in the Reagan revolution? Given that multiracial congregations make up only 8-10% of total church congregations in the United States, what does this mean for studying Peoples Temple?[3] By analyzing personal accounts and writings from Peoples Temple, I hope to find an answer to these intriguing and perplexing questions.

The history of the Peoples Temple Christian Church begins in the American Midwest in the 1950’s. Jim Jones was born into what he described as a “lily white town where Negroes were not allowed to remain after sundown.”[4] He also indicated that his father may have had ties with the Ku Klux Klan. He was born in 1931 just two years after the collapse of the stock market.[5] He was a child of the “old left” – the generation that experienced the terrible times of the Great Depression and the Second World War, followed by the Cold War.[6] Initially, Jones was drawn to the clergy when his wife Marceline showed him a bulletin for a church that indicated the support of the denomination for racial integration.[7] Barton and Dorothy Hunter remember that Jones, both at home and at the pulpit, was “very much concerned about racial integration, about the poor.”[8] Jones’ support for integration would cost him his first preaching job at Sommerset, and he parted ways with the Methodists.[9] After that Jones worked with the Laurel Street Tabernacle, and once again deserted the church due to his integrationist stance, walking out after being told he could set up a separate black church.[10] On April 4th, 1955, Jones and some of the congregants from the Laurel Street Tabernacle that had “voted with their feet” founded Wings of Deliverance, which would soon be renamed Peoples Temple.[11] Jones used the language of the Bible to preach the social gospel of racial equality, in a conscious effort to convert them to the cause of integration. The message was much more important for Jones than the biblical reality.[12]

Jim Jones did not just work in the public sphere through his church however. His commitment to the goals of the rising Civil Rights Movement was total. Jones planned to construct a “rainbow” family that would create the ideal racial situation and be a lesson to all the bigots raising havoc in Indianapolis about his radical church. In 1958, Jim and Marceline Jones started their “rainbow family” project by adopting two orphans from the Korean War, Stephanie and Lew Eric Jones.[13] Tragedy then struck the Jones’, when their daughter Stephanie died in a car accident. This left Jones in an ethical quandary. Where would his daughter be buried? Not in the segregated graveyards of Indianapolis, that was for sure. So Jones committed yet another radical act and had his daughter buried in a black cemetery, yet another public avowal of his belief in racial equality.[14] In 1959, Stephan Jones was born, and the Jones’ gave him the appropriate middle name of “Gandhi,” another example of civil rights support.[15] Perhaps the most radical act of the Jones’ during this period of racial upheaval was adopting Jimmy Jones Junior, an African-American child a little younger than Stephan, making the family the first in the state of Indiana to adopt a black child.[16] This did not sit well with more conservative elements of Indianapolis society to say the least. The less progressive elements of Indianapolis could only take so much agitation.

Soon the Jones family began to feel a backlash against their rainbow family and all that it represented. Marceline Jones was carrying young Jimmy Jones when a white woman accosted her and spit on her and the baby.[17] A stick of dynamite was found in a coal pile near Peoples Temple, eerily reminiscent of the Birmingham Church bombing. Jim Jones and some of his congregation reported phone calls late in the night, and hate mail was received at the Temple. A swastika was painted on the church door, and a dead cat was thrown into the congregation during a service. The situation grew so tense that Marceline blasted a hole through her closet door on accident with a shotgun when she thought she heard someone outside. Despite such attempts to thwart Jones’ campaign for racial equality, he still provoked the opposition, sending accusatory letters to American Nazi leaders and leaking their responses to the press. Peoples Temple withstood this campaign of terror and the congregants refused to abandon their belief in an interracial society.

Jones also underwent a personal campaign to affect change in Indianapolis. 1960 marked the beginning of the restaurant in the basement of Peoples Temple, a weekly free meal of which thousands were served. The Temple encouraged racial mixing in the dining area, mixing Christian charity with an attempt at social change.[18] In 1961 Jones was appointed Director of the Indianapolis Human Rights Commission, and used his new public forum to further his crusade against racist American society.[19] He told the press that he had walked out of a barbershop that refused service to a black man, and also claimed to have integrated three restaurants in the city.[20] In another instance that entered Temple lore, Jim Jones went to a hospital for an ulcer condition that had developed (radical politics being hard on the stomach). Reading that Jones’ doctor, E. Paul Thomas, was black, the hospital automatically assigned him to the segregated “black ward.”[21] When the hospital realized their mistake, Jones refused to leave, going so far as to wash the patients and change their bedpans. Despite Jones’ histrionics, he did manage to force the hospital to desegregate. Actions like these gave Jones the aura of a crusader, a man on a holy mission from God to overcome the legacy of racism that was infecting the American body politic. Potential converts were drawn to the congregation by appealing to their sympathy for the goals of the Civil Rights Movement.

Many people joined the Temple because of Jim Jones’ dedication to integration and racial equality. Bob Houston said he joined because it did not suffer from the “reactionary malaise” that was typical of institutions in the county. He “particularly appreciated the interracial aspects.”[22] Jones’ wife Marceline said that, “it was Jim who first made me aware of the race problem.”[23] Zipporah Edwards joined the Temple back in Indiana after seeing their integrated choir on television.[24] Dick Tropp joined the Temple after his involvement in civil rights protests and marches.[25] Vera Washington stated that she was from the South and also involved in the civil rights struggle, especially the voter rights drives. She offers the following statement about her reasons for joining the church. “Jim Jones was not just paying ‘lip service’ to the cause but was actively promoting interracial lifestyles. This was all very impressive to me, so much so that I joined the Temple.”[26] While in Jonestown, Pop Jackson stated that he was relieved of the racial pressures of American society.[27] Tim Carter had this to say about the Temple: “We did not exist in a vacuum. We were a reflection of the economic and political and cultural realities and dynamics of the civil rights and Vietnam War generation. Whether one’s intentions had been political or spiritual, the Temple seemed to offer the ideal opportunity to effect social change . . .”[28] The Temple newspaper, The Peoples Forum, also stressed civil rights. In the edition published on August 1, 1977, the paper was still pushing for civil rights reform. An article in the paper by Carlton B. Goodlett analyzed the murder of a gay man and urged coalition-building. He argued that people “must be encouraged extend their struggle to embrace the entire spectrum of civil rights.”[29] Profiles of members show that many joined because they were committed to the goals of the Civil Rights Movement and saw in Jim Jones a way to create the sort of society they wanted.

Jim Jones even preached to the choir in one instance, showing his uncompromising passion for radical racial equality. Attending a meeting of civil rights groups in Indianapolis – including such organizations as the Urban League and the NAACP – Jones delivered an impressive diatribe. Expecting a moderate speech praising behind-the-scenes maneuvering and patience, the audience was not expecting the white preacher to burst forth with a militant speech on racism that concluded with a scream of “Let my people go!”[30]

In the midst of upheaval at home, war in Vietnam, assassinations, the Cold War and the Civil Rights Movement, Jones honestly began to think that the apocalypse was drawing near. After reading an article in Esquire magazine that touted the Mendocino County region of California as a “nuclear safe zone,” Jones took a dedicated core of people and moved out West to try his hand in California society and build a “socialist paradise.[31]

On July 26, 1965 the residents of Ukiah, California were greeted with a seemingly mundane article concerning a new minister that had recently moved to town. The headline read “Ukiah Welcomes New Citizens to Community” and featured a picture of a clean-cut minister with his wife and four children.[32] The caption read “The Rev. Jones is pictured in his Redwood Valley home with his wife and their four children. Suzanne, James Jones Jr., and Lew Erick . are adopted children of Japanese, Korean, Negro, Indian and Caucasian heritage, and Stephan is their natural son.” The column opened with the words: “Ukiah has quietly gained over the past several months 140 new citizens devoted to a belief in the brotherhood of man – and living their belief in their daily lives.”[33] It described the new religious group Jones led, known as the Peoples Temple Christian Church of the Disciples of Christ, as gathering around one central idea, “that all men – white, black, yellow or red – are one brotherhood.” In the twenty-first century such statements have lost their radical ring, but during the turbulent 1960’s such sentiments were far more controversial. The denizens of “sleepy, rural Mendocino County” were about to embark on a decade-long encounter with a congregation born of the racial tensions wracking the country, and act out a scene reminiscent of those occurring in the South.[34]

The period of 1965-1976 (the year Peoples Temple officially moved to San Francisco) was Ukiah’s experience with the Civil Rights Movement and a civil rights style organization. One person who traveled with Peoples Temple described the region in the following passage:

Despite its picture-postcard name, Redwood Valley, California, is not really a picture-postcard place. A small farming community about two hours drive north of San Francisco, the town itself boasts nothing more scenic than a few gas stations, hardware stores, and farm machinery dealerships; but a few miles outside town the countryside rises into a line of pleasant – if unspectacular – rolling hills, some of them covered with stands of redwood trees, most of the others planted with vineyards.[35]

Ethan Feinsod would go on to write this about the community. “Although very little of it – either the events or the violent spasms of the body politic – touched anyone in Mendocino County directly, the issues involved – civil rights, the war, student protest – were as much discussed, as controversial, and as divisive as they were anywhere else in the country.”[36] I disagree with this passage, and see the coming of Peoples Temple as a result of the “violent spasms of the body politic” that directly touched the lives of the residents of the county. It was a small, intimate, mostly white community that did not have any experience with racial politics, but that was changing with the arrival of over 100 Hoosiers fresh from the struggle in Indianapolis. Even my own father would have his experience with the Temple and by extension the civil rights Movement, receiving a letter from church members extolling the virtues of Pastor Jim Jones.[37] The town without a significant African-American community on the West Coast, far from the South, was still affected by the seismic changes happening in the United States.

Jim Jones continued his campaign for racial equality in the Ukiah/Redwood Valley region. He taught at the local schools, in Redwood Valley, Potter Valley and Booneville and the Ukiah Adult School. Jones’ classes were very popular, especially his night classes at the Adult School. When Jones thought that the administration was spying on him, he had the windows closed at all times and posted guards at the doors.[38] The children of Temple members were required to get good grades in citizenship classes or explain to the congregation why they did not.[39] Jones also delivered sermons on patriotism and the responsibilities of citizenship to his flock.[40] The Temple members were made to understand the importance of the political process and voting, and tied their religious beliefs in with progressive politics that would erode the racist character of society. This is similar to many movements in the South that focused on teaching people the importance of voting and the electoral process in connection to their well-being.

Ukiah reminded some Peoples Temple members of the South. Hyacinth Thrash, one of the few survivors of Jonestown, offered this on the area. “Ukiah was in grape growing country. At that time Ukiah was more Southern in its attitude towards blacks. Before our church moved there, there was only one black family in the whole town. Zip [her sister, Zipporah Edwards] and I were the only blacks in our apartment building.”[41] Stephan Jones said of Redwood Valley, “if anything, it was worse. It was unbelievable. They acted like they had never seen a black person before. They acted like they were inhuman. You’d hear the chants everyday. Finally you got immune to it. There was at least one thing that was different about Redwood Valley – I wasn’t acceptable either.”[42]

The Temple would experience harassment at the hands of local agitators. One man marched into a sermon being delivered by Jones and verbally accosted him. When Jones stepped outside with the man, he threatened to stab him with a hunting knife.[43] Kathy Hunter wrote an article describing the problems the Temple was facing: threatening phone calls, being shot at, assaulted, called a “nigger lover.” Hunter suggested that: “perhaps a few white supremacists are offended by his inter-racial family.”[44] Even when Temple member went to Lake Mendocino to swim, some locals shouted racial epithets at them, leading Peoples Temple to construct a pool to avoid stirring up the local populace.[45] The situation got so tense that members started to carry guns. Jim Jones reportedly slept with a shotgun next to his bed.[46] The Temple began to resemble an armed compound.

At one point, dozens of Temple security guards with black uniforms and berets stood at attention in front of the church, ostensibly because the Hell’s Angels were coming their way.[47] The posturing evokes the image of the militant members of the Black Panther Party. After investigations into activities of the Temple and Jim Jones, the flock would move first to San Francisco and then to Peoples Temple Agricultural Mission (Jonestown) in Guyana.

History would remember another part of James Warren Jones’ career. The early years of his church and congregation would be overshadowed by the horrific events that occurred on November 18, 1978 in the small South American country of Guyana.[48]People with family members living in the compound in the jungle underwent a campaign to get their relatives out of Jonestown. This group, led by former Mendocino County assistant district attorney Tim Stoen, called themselves the “Concerned Relatives” and successfully convinced congressman Leo Ryan from Northern California to investigate the allegations against the group. When some members professed their desire to leave with Ryan, he allowed them to accompany his congressional party to the airstrip. Members of Jonestown tracked the party to the airport and ambushed them, killing Leo Ryan and others. Jim Jones convinced the residents of the town to commit “revolutionary suicide,” and those who refused were injected with poison. In the end, over 900 people committed suicide by drinking poisoned fruit punch or being injected with cyanide. Jim Jones himself died of a gunshot to the head, probably suicide. The dead bodies surrounding a vat of poison would be splashed across newspapers across the world the next day.

By February of 1979, 98% of Americans polled said they had heard of the tragedy. George Gallup said: “Few events, in fact, in the entire history of the Gallup Poll have been known to such a high proportion of the United States public.[49] The images of Jonestown would do far more than sell papers however. John Hall would comment: “The gruesome piles of bodies huddled next to one another attained an instant place in the United States collective consciousness.”[50] The final events of Peoples Temple have overwhelmed the discussion of the organization’s history and legacy.

It is my argument that Peoples Temple was a civil rights organization, born of the struggle to achieve gains for African-Americans, and belongs in the pantheon of groups such as SNCC and CORE. Although the group ventured into perplexing territory, the identity of the congregation was predicated on economic and racial equality. The early history of the church, both in Indiana and the Ukiah/Redwood Valley area is lost amongst the lurid details of the later years. The residents of Mendocino County experienced the Civil Rights Movement through Peoples Temple and the conflict that ensued.

The first wave of scholarship began immediately after the final “White Night” in 1978. Two of the reporters working to expose Jim Jones published a book entitled The Suicide Cult: The Inside Story of the Peoples Temple Sect and the Massacre in Guyana which hit the markets within a month and a half of the event.[51] It was “rushed into print well in advance of body identification” and is representative of the early work on Peoples Temple.[52] Sensationalism and finger pointing were the order of the day.[53]“Everything was sensational. Almost no attempt was made to gain any interpretive framework.”[54] Another source were ex-members of the Temple that published books detailing their experience, such as Jeannie Mills’ Six Years with God: Life Inside Reverend Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple.[55] The literature focuses on Jim Jones’ personality and the excesses that the church engaged in, with corporal punishment and sexual abuse. The following quote illustrates this: “But despite any culpability of government bureaucrats, investigators, or politicians, blame for the Jonestown tragedy must ultimately come to rest in the deranged person of Jim Jones.”[56]

Religious scholars have also written extensively on the latter portion of Peoples Temple history.[57] One author compared the Jonestown debacle to having the same paradigm-shattering effect as the great Lisbon earthquake of 1755 did on Enlightenment’s faith in intelligibility (see the work of Voltaire, especially Candide for a description of the earthquake).[58] Another popular format are pieces set entirely in Guyana, or deal mostly with the final days of Jonestown.[59] What most of these works have in common is a preoccupation with the perverse details of the church – what one scholar has identified as the “pornography of Jonestown.”[60]

With the passage of time, new aspects of the Peoples Temple story were studied. One major work that emerged was A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in the Peoples Temple, published in 1985.[61] Rebecca Moore’s work was one of the first to portray the members of the Temple as something more than mindless poison drinking cultists; she wanted to write a history of the believers, not ex-members or opponents. John R. Hall wrote what is perhaps the best work on Peoples Temple and Jonestown in Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural Historyin 1987. He critiques the previous scholarship on Peoples Temple, especially with casting Jim Jones as “insane” or “the Anti-Christ.” In the following quote Hall explains the effects of unsound scholarship: “By reducing history to a superficial atrocity tale, the writers who claim to reveal the true story instead place Jonestown beyond the reach of historical analysis.”[62] Hall’s work ushered in a new era of scholarship on Peoples Temple, and marked the beginning of a new understanding of the movement. Later works, such as Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, try to bring the study of Peoples Temple under the umbrella of black religious studies.[63] The work also critiques who studies the movement, and is evidenced by the following passage: “Most of the scholarly analysis of Peoples Temple, as well as of the movement’s settlement in Guyana, has been conducted by sociologists of religion using the theoretical framework of New Religious Movements (NRMs).”[64] Another article in the volume analyzes the role of Black Power rhetoric in the latter stages of the Temple’s history, tying it in to post-colonial theory and third world revolutionary movements.[65] This is the most explicit analysis of Peoples Temple in relation to the Civil Rights Movement I have discovered in the literature. It does not however, state that Peoples Temple was a civil rights organization that cannot be explained outside of the context of the Civil Rights Movement. While the later Civil Rights Movement is covered and the link is made between the Black Panther/Black Power rhetoric, the earlier Temple activities, such as in Indianapolis and Ukiah are not analyzed in the proper context.

An informative collection of primary sources from Peoples Temple collection at the California Historical society was published in 2005, which shows the direction the study of the Temple is taking.[66] What emerges is a historiography without historians.[67]The Civil Rights Movement is mentioned as a peripheral event to the story of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. Too much work has been done by sociologists of religion on the subject without examining the historical events surrounding, shaping, and being shaped by Peoples Temple. I call for historians to tackle this controversial area, and include Peoples Temple in Civil Rights Movement discourse.

Works Cited

Author Unknown, Ukiah Daily Journal, 12/21/1978, Peoples Temple Papers, Mendocino County Historical Society.

Carter, Tim. The Big Grey. the jonestown report, 2003.

Chidester, David. Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1988.

Feinsod, Ethan. Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown the Only Eyewitness Account. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1981.

Goodlett, Carlton B. The Peoples Forum. 8/1/1977. Vol. 2, No. 4. Peoples Temple Disciples of Christ. Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

Hall, John R. Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1987.

—–. “Jonestown in the Twenty-First Century.” Society. January/February 2004. Accessed through Academic Search Premier, 9/1/06.

Hall, John R. with Philip D. Schuyler and Sylvaine Trinh. Apocalypse Observed: Religious Movements and Violence in North America, Europe and Japan. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Harris, Duchess and Adam John Waterman. “To Die for the Peoples Temple.” Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. Eds. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn and Mary Sawyer. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004. pp. 103-122.

Hunter, Kathy. The Ukiah Daily Journal. 7-26-65. Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

—–. “Local Group Suffers Terror in the Night,” The Ukiah Daily Journal, 6/3/1968, Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.i

Kilduff, Marshall and Ron Javers. The Suicide Cult: The Inside Story of the Peoples Temple Sect and the Massacre in Guyana. New York: Bantam Books, 1978.

Jackson, David Betts. “Settin’ around here free this morning.” In Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. Ed. Denice Stephenson. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005. pp. 71-72.

Jenkins, Kathleen E. “Intimate Diversity: The Presentation of Multiculturalism and Multiracialism in a High-Boundary Religious Movement.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. September 2003, Vol. 42, Issue 3. pp. 393-409. Accessed through Academic Search Premier, 9/10/06.

Jones, Marceline. “Jim Jones as Seen through the eyes of those who he loved.” In Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. Ed. Denice Stephenson. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005.

Jones, Stephan. “We All Made the Move.” In Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. Ed. Denice Stephenson. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005.

Layton, Deborah. Seductive Poison: A Jonestown Survivor’s Story of Life and Death in the Peoples Temple. New York: Doubleday, 1998.

Mills, Jeannie. Six Years with God: Life Inside Reverend Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple. New York: A&W Publishing, 1979.

“Minister Reviled, Threatened,” The Ukiah Daily Journal, Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

Moore, Rebecca. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in the Peoples Temple. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1985.

Naipaul, Shiva. Journey to Nowhere: A New World Tragedy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981.

“Patriotism Topic of Temple Pastor,” The Ukiah Daily Journal, 7/10/70, The Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

Reiterman, Tim with John Jacobs. Raven: The Untold Story of the Reverend Jim Jones and His People. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1982.

Smith, Johnathan Z. Imagining Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

“Temple Takes Novel Citizenship Approach,” The Ukiah Daily Journal, 10/2/1970, The Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

Thrash, Hyacinth. In Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. Ed. Denice Stephenson. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005.

——. “Following Jim to California.” In Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. Ed. Denice Stephenson. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005.

Trell, Emmet, Jr, “Jonestown Revisited.” American Spectator. April 1999, Vol. 33, Issue 4. Accessed through Academic Search Premier, 9/10/06.

Tropp, Dick. Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. Ed. Denice Stephenson. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005.

Washington, Vera. “Reflections on Leaving the Temple.” In Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. Ed. Denice Stephenson. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005. pp. 64-65.

Wooden, Kenneth. The Children of Jonestown. New York: McGraw Hill, 1981.

[1] Kathleen E. Jenkins, “Intimate Diversity: The Presentation of Multiculturalism and Multiracialism in a High-Boundary Religious Movement,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (September 2003, Vol. 42, Issue 3), 393-409.

[2] Emmet Trell Jr., “Jonestown Revisited,” American Spectator (April 1999, Vol. 33, Issue 4).

[3] Jenkins, 393.

[4] Tim Reiterman with John Jacobs, Raven: The Untold Story of the Reverend Jim Jones and His People (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1982).

[5] Reiterman, 9.

[6] John R. Hall, “Jonestown in the Twenty-First Century,” Society (January/February 2004): 9.

[7] John R. Hall, Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1987), 24.

[8] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 25.

[9] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 17.

[10] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 42.

[11] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 43.

[12] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 44.

[13] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 117.

[14] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 47.

[15] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 47-48.

[16] The following paragraph draws from Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 48.

[17] Reiterman, 72.

[18] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 53.

[19] Reiterman, 68.

[20] Reiterman, 68.

[21] Reiterman, 75-76.

[22] Reiterman, 117.

[23] Marceline Jones, “Jim Jones as Seen through the eyes of those who he loved,” inDear People: Remembering Jonestown, ed. Denice Stephenson (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005), 13.

[24] Hyacinth Thrash, in Dear People,17.

[25] Dick Tropp, in Dear People, 72.

[26] Vera Washington, “Reflections on Leaving the Temple,” Dear People, 64-65.

[27] David Betts Jackson, “Settin’ around here free this morning,” Dear People, 71-72.

[28] Tim Carter, “The Big Grey,” Dear People, 155.

[29] Carlton B. Goodlett, The Peoples Forum, 8/1/1977, Vol. 2, No. 4, Peoples Temple Disciples of Christ, 2.

[30] Reiterman, 69.

[31] Reiterman, 77.

[32] The following section draws from a Ukiah Daily Journal article entitled “Ukiah Welcomes New Citizens to Community”, 7-26-65, Kathy Hunter, in the Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

[33] Hunter.

[34] Ethan Feinsod, Awake In A Nightmare: Jim Jones, The Only Eyewitness Account(New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1981), 3.

[35] Feinsod, 11.

[36] Feinsod, 13.

[37] Letter to Bill Silva, copy in possession of author.

[38] Reiterman, 99.

[39] “Temple Takes Novel Citizenship Approach,” The Ukiah Daily Journal, 10/2/1970, The Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

[40] “Patriotism Topic of Temple Pastor,” The Ukiah Daily Journal, 7/10/70, The Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

[41] Hyacinth Thrash, “Following Jim to California,” in Dear People, 22.

[42] Stephan Jones, “We All Made the Move,” in Dear People, 20.

[43] “Minister Reviled, Threatened,” The Ukiah Daily Journal, Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

[44] Kathy Hunter, “Local Group Suffers Terror in the Night,” The Ukiah Daily Journal, 6/3/1968, Mendocino County Historical Society, Peoples Temple Papers.

[45] Reiterman, 103.

[46] Reiterman, 104.

[47] Reiterman, 199.

[48] A good discussion of the final events in Guyana can be found in chapter 11 “The Apocalypse At Jonestown” in Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 254-288.

[49] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 289.

[50] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 289.

[51] Marshall Kilduff and Ron Javers, The Suicide Cult: The Inside Story of the Peoples Temple Sect and the Massacre in Guyana (New York: Bantam Books, 1978).

[52] Author Unknown, Ukiah Daily Journal, 12/21/1978, Peoples Temple Papers, Mendocino County Historical Society.

[53] One example is Kenneth Wooden, The Children of Jonestown (New York: McGraw Hill, 1981), which describes the abuse of children at Jonestown and places the blame on the Carter administration.

[54] Smith, Jonathan Z. Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988: 109. (Chapter 7, pp. 102 – 120, “The Devil in Mr. Jones”.)

[55] Jeannie Mills. Six Years with God: Life Inside Reverend Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple. New York: A&W Publishing, 1979.

[56] Reiterman, 577.

[57] A few examples of religious scholarship on Peoples Temple are David Chidester,Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown (University of Indiana Press, 1988), and John R. Hall with Philip D. Schuyler and Sylvaine Trinh, Apocalypse Observed: Religious Movements and Violence in North America, Europe and Japan (New York: Routledge, 2000).

[58] Smith, 104.

[59] Shiva Naipaul, Journey To Nowhere: A New World Tragedy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981), Deborah Layton, Seductive Poison: A Jonestown Survivor’s Story of Life and Death in the Peoples Temple (New York: Doubleday, 1998).

[60] Smith, 109.

[61] Rebecca Moore, A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in the Peoples Temple (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1985).

[62] Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, xvii.

[63] Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, Eds. Rebeca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn and Mary Sawyer (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004).

[64] Introduction, Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, xiii.

[65] Duchess Harris and Adam John Waterman, “To Die for the Peoples Temple,”Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, 103-122.

[66] Dear People: Remembering Jonestown, ed. Denice Stephenson (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005).

[67] Two recent examples of history without Jonestown or Peoples Temple are The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics, Bruce Schulman (New York: The Free Press, 2001); and Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore, James T. Patterson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). Strangely enough, Patterson’s work lists The Jerry Springer Show in the index, but not Jim Jones or Jonestown.