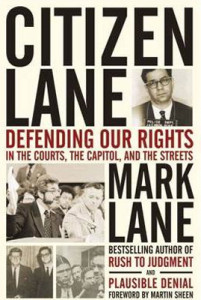

Preemptive CYA Disclaimer: Autobiographies are always a tough breed to assess. While there’s the temptation to take the tale as an inside-edition “setting the story straight,” there’s also the flip side we need to remember, that what we are reading is quite likely self-serving propaganda. Such is the case with Citizen Lane.

Preemptive CYA Disclaimer: Autobiographies are always a tough breed to assess. While there’s the temptation to take the tale as an inside-edition “setting the story straight,” there’s also the flip side we need to remember, that what we are reading is quite likely self-serving propaganda. Such is the case with Citizen Lane.

There are a number of claims in this book which made pings on my skeptical sonar. I will politely call them dubious. I am not, however, calling them false. I would never accuse a lawyer of lying unless I had concrete evidence of it, and in this case many of the claims are all but unverifiable. I am a skeptic at heart, and I am merely saying that I would like something more concrete than Lane’s word that, for instance, Paul McCartney signed an fan’s autograph “Paul McCartney, friend of Mark Lane” or that Lane had a private one-on-one dinner with W.E.B. Du Bois. These may well have happened – the autograph and the letter inviting Lane to dine are theoretically still out there – but until I see some pictures and an accompanying voucher from a handwriting expert, I will remain unconvinced.

This skeptical umbrella also covers many of his claims concerning Lane’s role in the Jonestown tragedy.

With that in mind, this “review” is presented as a recap of the relevant chapter of Lane’s autobiography, with no sanctioning of its authenticity or cries of foul to any potential mistruths. I will let readers more knowledgeable of the “facts” draw their own conclusions.

Citizen Lane: The relevant section is Chapter 18, pages 299-314, plus nine endnotes spanning pages 362-365. Lane begins by making it clear that he had only met Jim Jones twice – in September and November of 1978 – and he “had never heard of Jones or Jonestown until shortly before then.” His introduction came via his roommate, screenwriter Don Freed, who was friends with Peoples Temple attorney Charles Garry. At Garry’s invitation, Freed had visited Jonestown on a scouting trip for a possible documentary. Shortly after that, Lane got a cold call from a Peoples Temple representative inviting him down to Guyana to lecture on Martin Luther King, Jr. That visit, on September 15, 1978, is painted with a mixed palate: Lane seemed impressed with Jonestown but not its leader, whom he describes as “quite aged, far beyond his years, and appeared to be sedated or on some kind of medication. He had about him an air of desperation and defeat.”

After writing a tangent about Peoples Temple apostate and rabble-rouser Tim Stoen and his effort to get Congressman Leo Ryan to investigate Jonestown, Lane tells of another cold call from the Temple imploring him to accompany the delegation. “She said Jones trusted me, and she hoped that if any dispute took place, I might be able to play a calming role.”

The fateful trip itself is barely described, with the most attention being given to the nearly-lethal attack on Ryan by a Temple member and Lane’s seemingly single-handed effort to successfully thwart it. Ryan decided it best to make a tactical withdrawal at that point, albeit only “if I would stay to complete his work if he agreed to depart.” Lane took the assignment, but just after the rest of the delegation departed, he and Garry were herded into a shed and placed under watch while armed guards ran about and Jones began making announcements over the loudspeaker explaining “that it was best that they all die.”

As the gravity of the situation sank in, Lane convinced Garry that “since we were lawyers, our only chance for survival was to make a very persuasive closing argument.” Lane talked to their guards, imploring them to let him and Garry leave so they “would tell the truth to the world about what happened that day.” The guards agreed and let the two captives run off to the surrounding jungle. They promptly got lost, until Lane struck upon the idea of selecting a random location as a starting point and then heading off in different directions until they find the road, marking the trail back to the starting point with shreds of underwear. This eventually worked, and they arrived at Port Kaituma the next morning.

Lane concludes the tale with this commentary: “While the American government stated that a mass suicide had taken place and that the deceased had voluntarily consumed poisoned Kool-Aid, the Guyanese medical examiner concluded that many had been injected with cyanide and that the assertions by the officials of the United States that a mass suicide had taken place were not sustainable, since it was clear that there had been a mass murder.”

History Redux: Lane had already told his Jonestown story in book-length form with the 1980 publication of The Strongest Poison. Understandably, the chapter in Citizen Lane is an extremely condensed version of most of The Strongest Poison, though he does offer up the teaser in Citizen Lane that, “Of course, I am aware of many bizarre and complex factors that preceded the murders, and I will share them with you.” This statement is accompanied by an endnote that is essentially a plug for The Strongest Poison. Despite that bold statement that seemingly hints at new revelations about the tragedy, little if anything “new” is offered in the subsequent pages.

The two books are pretty much in sync in terms of the tale they tell. Indeed, I only found one extremely minor and one moderate contradiction across the two accounts.

Extremely Minor: In The Strongest Poison, the scissors he used to cut up his underwear to mark the attorneys’ jungle trail were a novelty he had bought several years previous to his trip; he had stashed them in his travel bag and promptly forgotten about them until he discovered them quite by accident in the jungle. In Citizen Lane, he had bought them (along with the underwear) immediately preceding his trip to Guyana, and he specifically spelunked through his bag to find them. Still, this strikes me as extremely minor, and I’ll give him a pass on it.

Moderate: In The Strongest Poison, Lane repeatedly asserts that the American embassy’s chief counsel to Guyana, Richard McCoy, was constantly passing along sensitive information to Jonestown about outside inquiries, such as the names of commune members that visitors specifically wished to interview. In Citizen Lane, the responsibility for this lapse in judgment is transferred to Deputy Chief of Mission Richard Dwyer. No explanation for this shift is given. Dwyer, of course, is an interesting figure in the tragedy’s milieu: long suspected to be a CIA agent – Lane specifically “outs” him as one – he frequently shows up on short lists of culprits penned by conspiracy-minded types. Undoubtedly, Lane’s comment will be grist for the conspiracy mills attempting to tie Jonestown to the CIA.

M.I.A.: As previously stated , Citizen Lane is a condensed version of The Strongest Poison, and much was left out for space considerations. It’s rather interesting what was left out. First and foremost, there is no mention whatsoever of Temple apostate Terri Buford or of Vita, the daughter she and Lane had. Likewise, Lane omits mentioning that he was hired by Peoples Temple to (at the very least) file some FOIA requests and offer advice on damage control counteroffensives.

The rest: In its totality, Citizen Lane is actually an interesting read. While I wouldn’t call it the “riveting…page turner…” that Martin Sheen declares in his introduction, it held my attention. Given my opening caveat of “assume this is true if…,” he has certainly led an interesting life. Indeed, someone cynically pointed out that you can actually make a drinking game out of this book: take a shot every time he name-drops someone famous he’s rubbed elbows with. (I myself don’t recommend playing, as participants would likely get cirrhosis of the liver a few chapters in.)

I had hoped to learn more about him in terms of his views on the Kennedy assassination – specifically if he had changed his mind or recanted any of his theories – and since he hasn’t and doesn’t, I found it a bit disappointing.

And with that being said…

The LOL WUT Moment: A few years ago there was an Internet phenomenon/meme known as “LOL WUT.” It was a slightly altered graphic of a giant, grinning piece of fruit that had the caption “LOL WUT” underneath. The picture, so preposterous that it simultaneously produced laughter and head-scratching befuddlement, frequently made its appearance in Internet forums, invariably in response to someone posting a comment in all seriousness that was ridiculously silly. For instance, if during a discussion on the BP oil spill, someone inveighs with the claim that “the spill was actually a complex cover-up to hide the discovery of Atlantis!” would almost certainly be greeted with a LOL WUT. Generally, when LOL WUT shows up in a discussion thread, it’s a good indication that the forum has either run its course/jumped the shark/nuked the fridge, or at the very least the person making claims should be put on ignore. With me so far? Good.

The LOL WUT Moment: A few years ago there was an Internet phenomenon/meme known as “LOL WUT.” It was a slightly altered graphic of a giant, grinning piece of fruit that had the caption “LOL WUT” underneath. The picture, so preposterous that it simultaneously produced laughter and head-scratching befuddlement, frequently made its appearance in Internet forums, invariably in response to someone posting a comment in all seriousness that was ridiculously silly. For instance, if during a discussion on the BP oil spill, someone inveighs with the claim that “the spill was actually a complex cover-up to hide the discovery of Atlantis!” would almost certainly be greeted with a LOL WUT. Generally, when LOL WUT shows up in a discussion thread, it’s a good indication that the forum has either run its course/jumped the shark/nuked the fridge, or at the very least the person making claims should be put on ignore. With me so far? Good.

This book actually has a LOL WUT moment.

Chapter 10 is a retelling of Lane’s creation and touring of his JFK conspiracy theory manifesto, Rush to Judgment. Pages 167-171 contain a bizarre, convoluted story where Lane claims to get an anonymous call from an assassin assigned to kill him – specifically by hitting him with a truck so it looked like an accident – but the assassin does not want to do the deed out of patriotism and is therefore warning Lane of the plot. The would-be hitman gives a lot of foreshadowing knowledge of Lane’s upcoming itinerary, including schedule appearances and exact hotel suites – intel that supposedly had not been worked out yet. Although never stated specifically, there is a less-than-subtle implication that the killer got his orders from some unnamed agency because Lane was getting too close to The Truth™. Obviously, the attempt never happened, and Lane lived on.

There are many reasons I don’t buy this, but let’s just go with the most obvious: I don’t think Rush to Judgment is anywhere near The Truth, so there’s no need to resort to an option that would otherwise certainly raise a lot of doubts and turn Lane into a martyr.

Others may disagree, of course, and if so, they are much closer to this book’s target audience than I ever will be.

(Other reviews of Citizen Lane appeared in The Hook and The Chicken Hawk.)

(Matthew Thomas Farrell is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His other article in this edition is Peoples Temple as Plot Device. His earlier writings for this site are collected here. He can be contacted at saint@extremezone.com.)