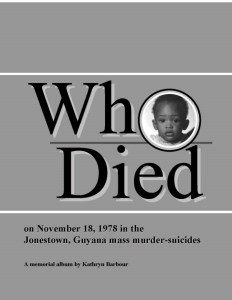

Earlier this year, I completed the work on the first edition of Who Died, a book which presents the photographs – mostly Temple membership or passport photos – of almost everyone who died in Guyana on November 18, 1978. The book makes a unique and substantive contribution to literary nonfiction on Jonestown and Peoples Temple. It should be seen by anyone who has an opinion on Jonestown.

Earlier this year, I completed the work on the first edition of Who Died, a book which presents the photographs – mostly Temple membership or passport photos – of almost everyone who died in Guyana on November 18, 1978. The book makes a unique and substantive contribution to literary nonfiction on Jonestown and Peoples Temple. It should be seen by anyone who has an opinion on Jonestown.

I first conceived of this work as a memorial album for families and friends. But after seeing the effect of them, shown as they were, on what we used to call “outsiders,” it became my aim and intent, one reader at a time, to replace the images usually associated with Jonestown’s anniversary with their faces, that they might be memorialized as are all others who pass—as they were in life. We will all die and decompose or be rendered to ashes. But only they bore the indignity of being endlessly and perpetually remembered in a state of decomposition. That insult added to the injury of being forever misunderstood.

Conventional wisdom, outraged at the deaths of innocent children, assigns culpability to almost all the adults, by virtue of their just being there. Confronted by the incomprehensible, most people distanced themselves from the pain of identification, taking refuge in their superiority, and holding adults who died in disgust, or contempt. That refuge is likely to be shaken by the images in this book, if not swept away, not by any argument made with words, but because you can’t look them in the eye and not realize how wrong all the generalizations – and how flimsy the rationalizations – are in the face of reality.

It is more than a little ironic that they should be tasked from beyond the grave with redeeming their own memory, and making that connection to the living that is usually done by survivors of death. On these pages they do that, but they do something more. They convey what we who survived feel mostly as a painful vacuum, but still cannot forget: The collective passion and empowerment that animated and motivated us, our identification with and love for each other and our cause, and our optimism and confidence in what we could accomplish, working together. Beyond individual beauty, en masse they present as the obviously vibrant society that was Peoples Temple, the most successful example of an integrated community ever built in the U.S.

This was all eclipsed in the shame and shock of the end. That is the greatest injustice, one we should try to remedy for their sake and ours. For instance:

I took a break from marketing the Who Died book last month to transcribe oral histories recorded by Laura Johnston Kohl. One person spoke of being still unable to properly grieve, or even to have feelings. That resonated hugely with me—I have felt exactly the same, but thought I was the only one! I suspect this applies to others. One way of coping with shame is by being in a virtual state of shock, even though to all appearances one is going about one’s life as usual. I was also struck by how fervently everyone described the congregation as the first attraction of Peoples Temple and what made them want to join.

I invite you to buy my book, if you haven’t! Spread the word to any who might be outside the loop. Share your copy with others who may be interested. Ask for order forms to take to your local library or favorite bookstores. And thank you for helping them to be remembered, as they really were.

(Kathy Barbour [Tropp] joined Peoples Temple in 1970 with her companion, Richard Tropp, and was living in the San Francisco Temple on November 18, 1978. Her other articles in this edition of the jonestown report are Mystery of the Last Tape Reconsidered and Channeling the Pioneers. Her earlier writings on this site can be found here.)