Mao Tse Tung said

Change must come,

Change must come

Through the barrel of a gun

– Jim Jones, as sampled in the song “Mao Tse Tung Said” by Alabama 3

Americans are susceptible to demagogues. Whether in politics, religion or popular entertainment, they like their messages delivered straight, loud, repetitively and without nuance. It’s fighting talk to declare this in some circles, but to me it explains the success of Bruce Springsteen, whose irony-free paeans to blue-collar American individualism lend themselves so well – and possibly through no fault of The Boss’ – to corporate mass-marketing and re-purposing as campaign slogans.

By contrast, the British distrust hucksters, demagogues and “the hard sell.” In order to persuade the English consumer to part with his hard-earned cash, it is often necessary to be oblique, clever, ironic, anything so that he does not feel hammered into the ground by the great blunt instrument of capitalism even as he willingly submits to the blows.

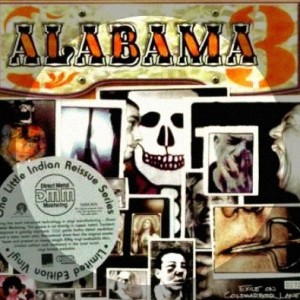

In Brixton, south London, there exists a band called Alabama 3, which plays American roots music, although they are not from Alabama and there are about nine of them. They wear Stetsons and drink Jack Daniels, and their early records consist of a unique fusion of techno dance music and C & W (“Genre: Sweet Mutherfucking Country Acid House All Night Long,” according to the band’s Facebook page). Their politics are radical and their recreational habits adventurous, which probably accounts for the fact that they rarely dare to tour America and are known here solely for having written and performed “Woke Up this Morning,” the theme song for The Sopranos. A founder of the band, one Jake Black, a Welshman, styles himself The Very Reverend D. Wayne Love, a redneck preacher from the deep South. The title of their brilliant first album, Exile on Coldharbour Lane, is itself a cheeky tip of the hat to The Rolling Stones, another, much more commercially successful, collection of naughty boys from south London who also like to test the limits of sincerity in American country music without (quite) toppling over into disrespectful pastiche. It is safe to say that Alabama 3 are ironists.

In Brixton, south London, there exists a band called Alabama 3, which plays American roots music, although they are not from Alabama and there are about nine of them. They wear Stetsons and drink Jack Daniels, and their early records consist of a unique fusion of techno dance music and C & W (“Genre: Sweet Mutherfucking Country Acid House All Night Long,” according to the band’s Facebook page). Their politics are radical and their recreational habits adventurous, which probably accounts for the fact that they rarely dare to tour America and are known here solely for having written and performed “Woke Up this Morning,” the theme song for The Sopranos. A founder of the band, one Jake Black, a Welshman, styles himself The Very Reverend D. Wayne Love, a redneck preacher from the deep South. The title of their brilliant first album, Exile on Coldharbour Lane, is itself a cheeky tip of the hat to The Rolling Stones, another, much more commercially successful, collection of naughty boys from south London who also like to test the limits of sincerity in American country music without (quite) toppling over into disrespectful pastiche. It is safe to say that Alabama 3 are ironists.

In Exile on Coldharbour Lane, Alabama 3 take on Jim Jones with the song “Mao Tse Tung Said.” As with the Stones’ best deconstructions of redneck country and western music on Exile on Main Street – which was recorded not in Nashville but from tax-exile at a villa in the south of France – the song is an affectionate, if mischievous, genre exercise. “Mao Tse Tung Said” is also a political song, a characteristically British spit-take at what the band perceives to be the abiding American obsession with guns and demagogues. Its dramatic coup, the effect of which is marvelous, haunting and strange, is the extensive use of voice samples from recordings made of Jones’ final sermons, delivered day and night over the PA in Jonestown:

So let Mao Tse Tung be your guidin’ star

Pick up a gun and learn how to fight

All thru the day and all thru the night

‘Til come the day when the last fight’s won

I want you to listen, son

The galloping tempo of the song ingeniously reflects Jones’ practised, folksy, increasingly urgent preacher’s cadence as he advocates armed revolution against an invisible foe, and it is this combination of homespun Americanisms (“son,” “oneliest way”) and exhortations to armed violence that would have appealed to Alabama 3 as essential representations of both the horror and the glamour of America. Unlike most casual observers of events at Jonestown and their causes, the band is fully aware that Jones had entirely subordinated his devout religious principles to a revolutionary, communist political agenda. This evolution is as rich in irony to European observers of America as the prospect of a Bernie Sanders White House; it is delicious and irresistible, all the more so for being doomed to failure. The song’s political “message” strikes me as so much sharper than Springsteen’s righteous bombast because it requires the artist to perform the neat trick of simultaneously taking America at face value while laughing in its face.

You cannot write as good a song as this, however, if its only purpose is to take the cheap shot, i.e. to heap contempt on corn-pone rabble-rousing. What makes “Mao Tse Tung Said” such a compelling protest song is the way that it employs a familiar, Lennon-esque aspect of English irony, which is to juxtapose irreverent pastiche with serious artistic purpose. This is how English pop-culture has processed meaning since the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts’ Club Band. The fact that a pop group of British scallywags addresses Jim Jones, using extensive samples of his own voice, is what’s known as “chutzpah” in Yiddish and as “whimsy” in English, yet the song transcends flippancy because Jones’ politics are taken very seriously by the band. Indeed, they are shared.

The long introduction of “Mao Tse Tung Said” samples Jones’ voice over a techno beat, an aural signature which immediately identifies the song as (forgive my choice of phrase) un-American. At the halfway point, however, as the tempo intensifies and Jones becomes more hysterical, the dance beat is superseded by a recognisable American square dance-style cadence, and Jake Black’s vocal takes over from Jones’ now demented rant. In more measured tones and not overdoing the American accent, Black reprises the sermon in Jones’ own words but without the histrionics. The effect of this is to confront us with the message by removing the distraction of the messenger. Change must come,

Not thru talkin’ and not through waitin’

And sittin’ around just contemplatin’ the facts

‘Cos we know what they are

So let Mao Tse Tung be your guidin’ star

In this way, the song de-stigmatises Jones’ message and dares us to appreciate both the content and the skilful rhetoric. This is genuinely subversive.

Much of the enigma of Jim Jones, Peoples Temple and Jonestown resides in how it challenges our concept of agency, i.e. the exercise of individual free will. In order even to frame an understanding of events in Jonestown, we must recognise a paradox, which is that Jim Jones was extraordinarily successful in imposing his will upon a collective, the most influential members of which were college-educated liberals who might have been expected to resist such an imposition. Idealists, free-thinkers, intellectuals, these were people whose involvement in revolutionary politics must surely have been built upon an imperative to speak truth to power, yet they died in thrall to a form of power – Jim Jones – that few of them appeared able to resist. Jones was initially the opposite of an embodiment of power; he was an instrument of liberation from the abuse of power in America. Rock music, too, once served this purpose, as a voice of freedom, from the arbitrary exercise of power, from the imposition of a collective will, from propaganda. Yet the difference between art and propaganda is that art encourages free thought where propaganda encourages conformity masquerading as idealism. Jim Jones fell into this black hole; sadly, much popular art in America (music and film in particular) has followed him down the same abyss, enabled by a lazy, blind complicity between its consumers and the corporations that control its production and distribution. If we expect to live in freedom, we must learn to recognise the difference between cultural expression that questions power and that which merely reinforces it.

(The song “Mao Tse Tung Said” is also available here and here. A live version appears here.)

(Barry Isaacson is a regular contributor to this site. His previous article is Navigating the Shoals of a Jonestown Story. He may be reached at barry90039@yahoo.com.)