As I continue work on my opera about the unique role Christine Miller played in the life and death of Peoples Temple – which I wrote about in the jonestown report 14 and the jonestown report 11 – I find myself ever more fascinated with her story. Here, in the midst of Jones’ oppressive tactic of obedience through sleep deprivation and cruel punishment, was one follower who spoke out against his “revolutionary suicide” order of November 18, 1978. Christine’s attempt to dissuade Jones and her fellow Jonestown residents is preserved on the “Death Tape,” which has now become my primary libretto source.

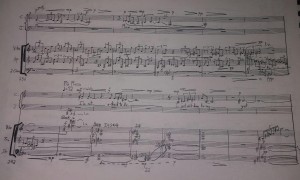

For the past several years, my life has alternated between cycles of conducting multiple choirs and working on this opera. The idea is to create a substantial scene, which can first be performed in an unstaged, concert version to demonstrate the feel of the projected final opera. I’m happy to say that as of a few weeks ago, that scene is completed, save for a few cosmetic scoring details.

I believe that Christine spoke as a proxy for all of the Jonestown residents. Perhaps she was more pre-disposed than others to counter Jones’ will, being more individual by nature, but in the end, it could have been any one of them in that position, including those who despised her for contradicting the established orthodoxy. I believe she attempted to appeal to all of their higher wisdom as deeply feeling human beings who had joined Peoples Temple originally for good and pure reasons. That means that the dynamic among Christine, Jones and the crowd must be central in my depiction of the final day. It constantly changes, befitting the fluid nature of events swirling around all of them. And it reflects my belief that the same people who shouted Christine down were trying, beneath the surface, to listen to a voice within them that knew she was right. Therefore, the chorus in this opera – representing the crowd – sometimes responds in agreement with Christine, repeating and sustaining her words as she says them, and other times joins in agreement with Jones. This is no reflection on them, but on Jones’ sadistic manipulation of them.

The first 10 minutes of this scene show part of Christine’s dialogue with Jones. Here is an audio sample of that dialogue, and an unidentified woman’s objections to Christine’s points.

We also hear from Jim McElvane, whose high-pitched defenses of Jones are always somewhat comically accompanied by a Hammond organ. Early on, though, I realized we would need a big, extended solo for Christine, a crucible moment to focus her prior arguments in an all-or-nothing, lay-it-on-the-line kind of way. This eloquent appeal would need to flow unimpeded, so that the audience might feel the tension I sometimes feel listening to the silences and pauses of the Death Tape, that at any given moment the crowd might have been swayed against Jones. The problem is, nowhere on the Death Tape does she speak for more than a few seconds without being interrupted.

So I had to write my own libretto for Christine’s signature aria. Departing from the transcript, I loosely based it on research – much of it available on this site – into what she was known to say or think before November 1978.

Christine begins with a defense against multiple accusations from the crowd, particularly one person – that she isn’t really one of them, that she doesn’t believe in their mission, that she’s scared to die, that she wants to defect, as the 15 people who left with Congressman Ryan had earlier that day. After all, she had just dared to suggest that everyone there had “the right to our own destiny as individuals.” This went against the Temple’s socialist culture, which, more than anything, was there to keep people’s opinions and goals in line with Jones’. Christine’s defense, however, is not delivered “defensively,” but sweetly and lovingly, accompanied by gentle undulations of piano and harp. Gradually she becomes more passionate (accented by English horn, clarinet and celesta), but never strident. Here is the text:

Dad, I believe.

Dad, I believe in us,

in what you’ve always said,

that we can reach our full potential

if we stay with you.

I still want that!

I been workin’ for that this whole time,

we all have!

We ain’t there yet, Dad!

Can’t get to there if we don’t survive.Who’s gonna hear your words,

who’s gonna share our vision

in forty years,

if we call it quits now?

How’s it gonna advance The Cause,

lying down dead in Guyana?

How we gonna fight for truth and justice then?We’ve come too far,

too far to leave all you built here,

here and in California too.

[hums quietly to herself]

I’m not afraid to die,

I just ain’t done living yet.

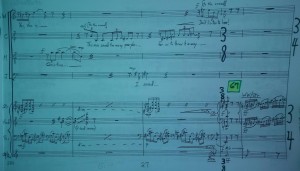

Addressing Jones and the crowd alternately, Christine realizes she must appeal to Jones’ vanity (2nd paragraph). At this point, we hear a melody which appears several times throughout the opera, most recently after a furious Jones diatribe about revolution. I think of this melody as his “delusion of grandeur” motif, or perhaps his “military paranoia” motif. Often it is heard from the full brass section, fortissimo. Here in the aria however, as Christine invokes Jones’ historical importance, it is played softly by a single muted trumpet, in a musical environment more wistful and hopeful than bombastic. Eventually the full brass do get a brief loud summation, as she references “truth and justice.”

Toward the end of the aria, after she mentions California, Christine slips into a reverie, humming to herself as gentle undulations evoke the aria’s opening, now with harp and vibraphone. I think of this as her returning to the idyllic early days, when their lives were more about fellowship than how to survive Jones’ descent into madness. The aria ends with Christine’s declaration for life, addressed to the crowd, as the harp fades out, leaving an ethereal high B in the violin section.

This moment – at the end of her aria with that tiny stratospheric violin note still hanging in the air – is potentially the turning point of the opera. What is going to happen? After a long, chaotic back-and-forth sequence, we’ve had five whole minutes of just Christine, not a peep from Jones or the crowd. Are they riveted, or just stoic? It feels like she may finally have them. When she dreams of better times in California, are they not also dreaming? This is what I mean about her being a proxy for them. They all want something better than what Jones has in store for them, and their higher selves know it. Unfortunately, he locked their higher selves away a long time ago. We already know where this is headed, but maybe, for just a moment as Christine’s logic sinks in, we might forget that we know.

This moment – at the end of her aria with that tiny stratospheric violin note still hanging in the air – is potentially the turning point of the opera. What is going to happen? After a long, chaotic back-and-forth sequence, we’ve had five whole minutes of just Christine, not a peep from Jones or the crowd. Are they riveted, or just stoic? It feels like she may finally have them. When she dreams of better times in California, are they not also dreaming? This is what I mean about her being a proxy for them. They all want something better than what Jones has in store for them, and their higher selves know it. Unfortunately, he locked their higher selves away a long time ago. We already know where this is headed, but maybe, for just a moment as Christine’s logic sinks in, we might forget that we know.

Into the ethereal sustained violin note, a quiet Hammond note floats in, then another, then a few others. Oh boy … McElvane. Indeed, the peace is gradually shattered as McElvane asserts that Christine owes her whole existence to Jones. Jones tepidly plays good cop, granting Christine the right to speak her mind, but an agitated string ostinato ushers in more piling on from the crowd, and it all goes to hell. The woman who accused Christine of cowardice is back at it, McElvane is clucking away – all as Christine herself tries to maintain her composure – until Jones finally rides the chaotic wave, as he does so well, into a horrifying soliloquy (heard in this audio clip) comparing himself to the disciple Paul, and concluding that “the best testimony we can make is to leave this God-damn world!” His “military paranoia” motif soars through the orchestra. This time he has the crowd’s emotions firmly in hand, and they roar their approval in a climactic chorus and orchestra moment.

Into the ethereal sustained violin note, a quiet Hammond note floats in, then another, then a few others. Oh boy … McElvane. Indeed, the peace is gradually shattered as McElvane asserts that Christine owes her whole existence to Jones. Jones tepidly plays good cop, granting Christine the right to speak her mind, but an agitated string ostinato ushers in more piling on from the crowd, and it all goes to hell. The woman who accused Christine of cowardice is back at it, McElvane is clucking away – all as Christine herself tries to maintain her composure – until Jones finally rides the chaotic wave, as he does so well, into a horrifying soliloquy (heard in this audio clip) comparing himself to the disciple Paul, and concluding that “the best testimony we can make is to leave this God-damn world!” His “military paranoia” motif soars through the orchestra. This time he has the crowd’s emotions firmly in hand, and they roar their approval in a climactic chorus and orchestra moment.

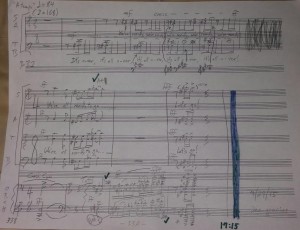

The post-aria text is largely drawn from the Death Tape transcript, and I found myself poring through it for scraps of crowd comments to use as the text of this last choral bit. And find them I did, just not where I expected. From mundane “Yeah’s” and “Right on’s,” we hear them sing “What a legacy!” and “We’re all ready to go!” But wait. Jim Jones actually said the former, and McElvane said the latter, from different parts of the transcript that look unlikely to make it into this opera.

If I set the entire transcript, it would last eight hours, and people would start leaving after one or two. As captivating as the Death Tape is, operatic time moves much slower than real life or even theatre time, so only a fraction of what I’d like to set will ever get set. Some liberties get taken to make things work in the genre at hand, and in this case, giving the frenzied chorus “What a legacy!” and “We’re all ready to go!” was right as rain.

I can’t say that imagining this scenario after the aria, or trying to find its accompanying music, was pleasant. To the contrary, it was quite painful, and entirely necessary. Jones’ final statement and the chorus’ response lands us solidly in F# minor, which some say is the darkest of keys. Mind you, usually my music is not even tonal, so landing in any “key” – even briefly – is a surprising event, for me as well as anyone. As I realized what was happening in the music, it broke my heart a little. And I thought, well hopefully it works, then.

I can’t say that imagining this scenario after the aria, or trying to find its accompanying music, was pleasant. To the contrary, it was quite painful, and entirely necessary. Jones’ final statement and the chorus’ response lands us solidly in F# minor, which some say is the darkest of keys. Mind you, usually my music is not even tonal, so landing in any “key” – even briefly – is a surprising event, for me as well as anyone. As I realized what was happening in the music, it broke my heart a little. And I thought, well hopefully it works, then.

There’s so much more work ahead. But this little arrival was quite a relief, and I hope it does some degree of justice to an unimaginable event in history.

(Perry Townsend is a composer based in New York City. He can be reached at ptownsend@immerbox.com.)