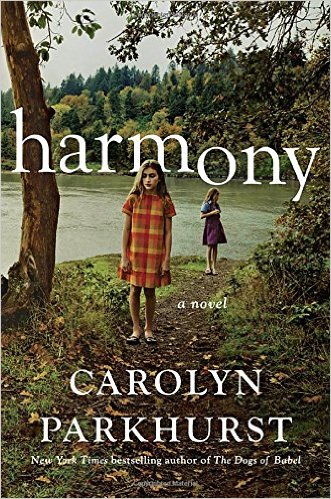

The realistic novel, Harmony, written by Carolyn Parkhurst (Pamela Dorman Books/Viking, 2016), tells the story of a family from Washington, DC that is struggling to manage the balance of an “undiagnosable” daughter with a more “normal” daughter. The passive-aggressive daughter, Tilly, has been expelled from yet another school in their suburb and her parents, Alexandra and Josh, are now searching for answers to make life with her more manageable. She has some type of mental disorder that prevents her from behaving in a publicly acceptable way, but that she is nevertheless extremely intelligent and courageous. Iris, the more normal daughter, is very wise for her age and proves to be the glue that actually binds the family but her wants and needs are often overlooked because of the blatant partiality for Tilly. The early part of the story shows many contrasts of character and provides a narrow window into the lives of families who escape day-by-day reality for a more private and non-negotiable lifestyle.

The realistic novel, Harmony, written by Carolyn Parkhurst (Pamela Dorman Books/Viking, 2016), tells the story of a family from Washington, DC that is struggling to manage the balance of an “undiagnosable” daughter with a more “normal” daughter. The passive-aggressive daughter, Tilly, has been expelled from yet another school in their suburb and her parents, Alexandra and Josh, are now searching for answers to make life with her more manageable. She has some type of mental disorder that prevents her from behaving in a publicly acceptable way, but that she is nevertheless extremely intelligent and courageous. Iris, the more normal daughter, is very wise for her age and proves to be the glue that actually binds the family but her wants and needs are often overlooked because of the blatant partiality for Tilly. The early part of the story shows many contrasts of character and provides a narrow window into the lives of families who escape day-by-day reality for a more private and non-negotiable lifestyle.

After seeing flyers promoting Mr. Scott Bean’s Counseling Services, Alexandra decides to attend his local seminar. Even though the mother has questions about the fact that Scott is single and without children of his own, she decides that he speaks to every need and desire that will benefit Tilly (and ultimately the family). When Scott visits their home and meets the family, he watches the daughters to get a better picture of the family’s struggle. Eventually, the family becomes devoted to Scott’s ideas and services, and they decide to take residence with Scott and other families at Camp Harmony in a secluded part of New Hampshire.

The author does the reader a favor by varying perspectives of the family’s life. One chapter will provide insight into Alexandra’s view of situations before, during, and after the move to Camp Harmony. The next chapter gives Iris’ perspective on situations that mostly occur within the camp. Ms. Parkhurst writes Tilly’s perspectives, not as a direct reflection on the events that are happening around her, but the way her brain analyzes and “experiments” with viewpoints on events and situations in which she is involved.

Students and survivors of Peoples Temple will appreciate this book because of the way it reflects many aspects of Temple membership. For example, the followers of Scott Bean know little about him, other than his public persona, and even though they have questions about their futures with him, they take him at his word. Families leave their routine lives behind to follow this man to a place of promised “harmony” and solitude that makes the unwanted world disappear. After arriving in New Hampshire, many campers discover the harsh reality of leaving behind all they know, and (at times) Scott becomes the opposite of what his followers previously thought of him.

Families at the camp are encouraged to accept all others as family, not just their own. Everyone is responsible for others’ children, and each family accepts this idea. Campers are expected to garden and grow food for the entire community; punishments are given as a result of poor work.

Eventually, Scott begins to disconnect camp families from the outside world. He sees the camp as the most important thing in his life and what should be the most important thing in the campers’ lives. Families with relatives in the camp begin a movement to discredit Scott Bean and his ideas. They even dig up information about his past that is unknown to some of the families at Camp Harmony.

Because the story takes place in 2012, campers have technologies which were unavailable to Jonestown in 1978. With their cell phones, they are able to communicate with the outside world, that is, until Scott removes this privilege. Facebook has involvement in the story because of relatives’ intervention tactics. Camp Harmony is also closer to civilization than Jonestown; families are able to drive to camp and around the local area. The father of one of the campers is even able to take his daughter Candy, as well as Iris and Tilly to a local fair.

Close to the end of the work, the story takes an unexpected turn that leaves campers speechless and in question of their next move. The author is careful not to mention groups of people that parallel the storyline but at the novel’s conclusion, Scott Bean names Jim Jones as a parallel to himself. The campers finally discover many truths about Scott and why he decided he could lead such a movement. Iris, Tilly, and Alexandra begin to reflect upon what is to come for the family and others at Camp Harmony. Obviously, the title of the story is contradictory to the motives of Scott Bean, but one might argue that the contradictory aspects also live on in the moderately dysfunctional family at the core of the story.

I recommend this story to anyone interested or involved with Peoples Temple or other social movements, teachers, parents of children who struggle behaviorally and socially, and parents who may simply see their child as “different” or unaccepted by those around them.

Ms. Parkhurst is also the author of The Dogs of Babel, Lost and Found, and The Nobodies Album. Her website is at CarolynParkhurst.com.

(Matthew Fulmer is an elementary teacher of 15 years and has been researching Peoples Temple and Jonestown for several years. He resides in Florence, Alabama. His previous book reviews for the jonestown report are for Children of Jonestown and Before White Night. He may be reached at mathewfl79@gmail.com.)