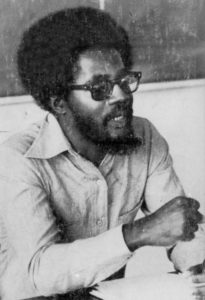

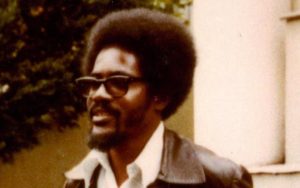

(This article is adapted from an address to the Walter Rodney Foundation in Atlanta, Georgia in March 2017. Walter Rodney was a political figure and leader of the Working People’s Alliance in Guyana during the Temple’s final years in Jonestown. He was killed by an explosive device in his car in June 1980, an assassination which has since been linked to the government of Guyana’s Prime Minister Forbes Burnham. Information on the Walter Rodney Foundation website includes a report of the Commission of Inquiry into Rodney’s death and a petition asking the Government of Guyana to take action on it.)

(This article is adapted from an address to the Walter Rodney Foundation in Atlanta, Georgia in March 2017. Walter Rodney was a political figure and leader of the Working People’s Alliance in Guyana during the Temple’s final years in Jonestown. He was killed by an explosive device in his car in June 1980, an assassination which has since been linked to the government of Guyana’s Prime Minister Forbes Burnham. Information on the Walter Rodney Foundation website includes a report of the Commission of Inquiry into Rodney’s death and a petition asking the Government of Guyana to take action on it.)

Guyana was not Peoples Temple’s first choice.

In fact, the Temple started off looking at other countries to establish a colony.

So why Guyana?

From the moment Jim Jones established Peoples Temple in Indianapolis in the mid-1950s, he seemed to have his eye on someplace else. It didn’t matter where he was, there was always someplace else he wanted to go. Even before he took his group to Northern California in the mid-1960s, Jones had taken his family to spend a year in Brazil, during which time his church suffered a nearly-fatal crisis in leadership.

The exodus from Indianapolis a few years later was in response to Jones chasing the carrot as much as it was him feeling the stick. The popularity of Peoples Temple represented a threat to some circles of power in Indiana – at least that was what Jones said, and there is some evidence to back that up – but he was also convinced that nuclear war was inevitable, and he wanted to go someplace where chances of surviving it were best. In the early 1960s, Esquire Magazine listed the area around Ukiah in Northern California as one such place.

That’s where the Temple moved in 1965. It started over almost from scratch, since fewer than 100 people accompanied Jones, but soon the Temple began to grow again. By 1972, it had three facilities in California: its original landing spot in Redwood Valley, and churches in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Definitive membership numbers are impossible to nail down, but it is true that by the mid-1970s, more than 5000 people had made enough of a commitment to the group that they had membership cards, and I believe the estimates that between 16,000 and 20,000 people attended Temple services at one point or another are accurate.

In California as in Indianapolis, however, Jones eventually ran into opposition, but that was okay with him, because he was increasingly fed up with the society that was slowing him down. His increasing political activism threatened to create tax problems for him; ministers of the black churches – especially in San Francisco – were uniting in opposition to him; and the press coverage about the group had suddenly turned negative. It all demonstrated that American society was antagonistic to his goals. The only way they could establish a paradise on earth was to create one, and the only place he could do that was somewhere abroad.

But where could he go? What was Peoples Temple really looking for as an alternative? Jones had several criteria: he was looking for a place with a socialist government (or at least one which had placed itself in opposition to the United States); a place with a significant black population (especially if blacks were in power); a place with a suitable climate; a place close enough to the United States that the Temple could move large numbers of people without too much cost; and a place which preferably spoke English. When you come right down to it, there weren’t many candidates.

Jones initially flirted with the idea of going to Brazil – not only had he lived there once before, it was also true that Belo Horizonte was one of the other locations which Esquire had declared as a safe zone in the event of nuclear war – but, among other things, there was a language barrier, and it was a long way away. In his own perfect world, Jones would have moved his group to Cuba, but there, the language barrier would have been more easily surmounted than the complications of Americans moving to an avowed Communist state, and that doesn’t take into consideration the clashing cults of personalities between Jim Jones and Fidel Castro. Jones did consider Belize, but it wasn’t leftist enough for him, and after all, he was looking to poke U.S. society in the eye with his dissatisfaction through the emigration of a thousand Americans. The Caribbean island of Grenada was a serious contender, and the Temple actually entered into negotiations with the government of socialist Prime Minister Eric Gairy for a sizable piece of land along the island’s coast, but negotiations ended when Gairy got a better offer from another bidder.

That left Guyana, and Guyana was the only option he pursued.

Even after Jones succeeded there, though – even after the Temple had established the community of Jonestown and a thousand people lived there – he continued to look for the next perfect place. He said he had a plan to move to the Soviet Union. He went so far as to invite Soviet diplomats from Georgetown to visit, and to require Jonestown residents to take classes in the Russian language. He also spoke periodically of an emigration to an unnamed African nation.

In my view, these were nothing more than diversions. Jones’ real exit strategy was one of mass suicide, which he cloaked in the garment of Black Panther Party rhetoric of revolutionary suicide. He began talking about it while the Temple was still in the States, and in the 16 months of Jonestown’s fully-populated existence, it became part of the daily conversation. He was just looking for the trigger. And in November 1978, the visit of a U.S. Congressman gave it to him.

Leo Ryan, whose California district included several families with relatives in Jonestown, announced a fact-finding tour to check out the conditions for himself. As it turned out, Ryan was impressed by what he saw, but it was also true, he escorted 16 disgruntled residents out of Jonestown and was preparing to take more. The defections were secondary to Jones’ decision, though. He had already declared that Ryan would not leave Guyana alive, and after he ordered the assassination of the congressman at the Port Kaituma airstrip, he announced that the community could not survive what he referred to as the “stigma” of that act, and so they would have to all die. At the end of November 18, 1978, there were 918 dead: five at the Port Kaituma airstrip, including the congressmen and three reporters, three in Georgetown, and 909 in Jonestown itself. That number included eight native-born Guyanese, all of them children, with the oldest being 16, all of them adopted or in the process of being adopted by Jonestown residents.

* * * * *

How did Peoples Temple end up in the remote Northwest District of a country that only a handful of people who died there had ever heard of? What kind of deal did Peoples Temple strike with Guyana, or more specifically, with the government of Forbes Burnham?

Unfortunately, most of the government’s official records of its contacts with the Temple were destroyed in a fire in Georgetown in 1979, the fire for which Walter Rodney was arrested. There are some who believe that the fire was deliberately set by the Burnham government to erase all traces of its involvement with Jim Jones – and they cite reports that men in uniforms of the Guyana Defense Force were seen running from the fire – but Burnham had many deeper and darker secrets than his relationship with Peoples Temple.

Fortunately, the Temple itself left behind fairly substantial records, including thousands of pages of documents and hundreds of tapes. With that said, we know there were many more tapes that were destroyed by the Temple than were preserved. That means we are left with a mosaic with a bunch of tiles missing. As a result, we have historical records, but we don’t have a complete history.

So with that caveat:

Forty-three years ago, when negotiations between Guyana and Peoples Temple began, the Burnham government was in the midst of one of the country’s recurring campaigns – which have had varying degrees of success – of developing the interior of the country. To refer to the Northwest District sparsely inhabited would be generous. And you can imagine just how small Port Kaituma was in the 1970s, in the days before its boomtown population generated by recent gold-mining. When Rebecca Moore and I visited Jonestown in 1979, six months after the tragedy, Port Kaituma was known almost solely as the town where manganese ore from Matthews Ridge was shipped downriver, and the mine itself had been closed for more than a decade. There was a single-lane dirt road and a railroad line, both about 30 miles long, between the two towns. Jonestown was located off that road, about six miles from Port Kaituma. There were a few other facilities out there – a youth camp, a training center for the GDF – and of course, an untold number of AmerIndians living in the jungle. But in terms of a sustainable economic infrastructure within the interior of the Northwest District, there wasn’t much.

Jim Jones gave Forbes Burnham an opportunity to change that. And that’s what Jim Jones undoubtedly promised Burnham he would bring. He told the people within the Peoples Temple congregation that they would grow enough food, not only to support Jonestown, but also to trade with local merchants and to donate to the people of the region who didn’t have enough to eat. The Temple also promised to bring health-care to the region. Its own promotional materials said it would import enough medical equipment to service, not only the 1000 people expected to live in Jonestown, but also for people in surrounding communities who needed it. The Temple told the inhabitants of the region the same thing.

Unfortunately, as it turned out, Jonestown didn’t grow enough crops to sustain itself, much less any Guyanese outside its gates, and – as Rebecca and I learned when we were there in 1979 – the Temple provided only limited medical services to outsiders, and that was only if they presented themselves at the project. In other words, there was no outreach. The false promises the Temple made – and continued to make, even after it knew it couldn’t deliver on them – is one of the few things I have not found in my heart to forgive.

There was one other consideration which influenced Burnham’s offer of acreage in the Northwest District – as opposed to, say the East Berbice-Corentyne region of Guyana – and that was its proximity to Venezuela. The boundary between the two countries has been in dispute for decades, but it is a dispute which attracts no international attention. Burnham knew that he would strengthen his own claim to the region by placing Americans there. If Venezuela were ever to launch a cross-border incursion, Caracas wouldn’t be answering only to Georgetown, but also to Washington, D.C.

Whatever the representations made by the Temple to Prime Minister Burnham, the deal that it got in return was very favorable. The first settlers from the States arrived in early 1974 to start clearing jungle and in fact had developed the tract of land for about two years before the two parties even signed a lease. In February 1976, the Guyana Commissioner of Lands and Surveys, and a representative of Peoples Temple, signed a land lease granting the use of 3852 acres to the Temple. The initial lease period of 25 years took effect almost two years retroactively and – most significantly – established the initial rental for the land at 25 cents per acre, a reduction from the rate of $2.00 per acre included in most such leases. It also allowed extensions of its terms for additional 25-year periods.

Of course, the problem with having Jim Jones in your backyard is that you have to deal with Jim Jones, and the Temple continued to seek special favors from the government. I’ll give you two examples.

Under Guyana law, new schools have to go through an accreditation process before they can be recognized – as Jones termed them – as “legal schools.” In the interim, school-age children were supposed to attend existing local schools. That would have meant that Jonestown children would have had to travel to Port Kaituma for their education. But that wasn’t Jones’ main concern. By March 1978, he was openly calling for his community’s “isolation” – again, his word – from the area’s existing communities, which would seem to run counter to everything he had once promised. In terms of the school, that meant he wanted immediate and unrestricted accreditation, and he claimed he would do anything to get it. On various nights, he reported to his people that he had threatened the government with what Jim Jones termed a “White Night”: they would act out in defiance of any authority, and if the authorities seemed as though they would prevail in its demands, the people of Jonestown would all die. As Jones boasted, the government backed down on its own rules, and Jonestown got its school.

The same thing happened with the Jonestown doctor. Larry Schacht had completed medical school, but hadn’t yet gone through internships and licensing in the United States, much less transferring any credentials to Guyana. Again, Jones said he threatened the government of Guyana with a White Night, and the government backed down. Whatever Jones actually did, the process of licensing Schacht to practice medicine in Guyana was cut by years.

At the same time, Jim Jones knew who his friends were, as well as the people who opposed him. Among his friends, Jones counted Burnham himself, Deputy Premier Ptolemy Reid, Minister of Home Affairs Vibert Mingo, Minister of Foreign Affairs Fred Wills, and Minister of Health and Labor Hamilton Green as his friends. His complaints were directed towards such men as Desmond Hoyte, at the time Guyana’s Minister of Development, Minister of Justice Mohammed Shahabadeen and Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Hubert Jack. Jones acknowledged a closer affinity to Cheddi Jagan, but Jagan was a member of the opposition party, and that limited whatever relationship Jones might have wanted to have. He expressed admiration for Walter Rodney, and even read a favorable review of Dr. Rodney’s book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa over the Jonestown public address system one night, but couldn’t trust having a relationship that might have upset Burnham.

Jones’ fealty to Burnham could – and did – have paranoid overtones. Burnham and several members of his cabinet left the country for a week in September 1977, the same week that one of the Temple’s adversaries in the United States tried to serve legal papers on Jones. The result was what was known as the Six Day Siege, during which men, women, and children armed themselves with farm implements and cutlasses, and stood of the perimeter of Jonestown for days, expecting an armed assault by the GDF.

To ensure his position of favor, Jones involved himself with numerous agencies and personalities. There are hundreds of pages of reports of meetings between Temple members and Guyanese government officials, mostly documenting aboveboard meetings, that is, official delegations visiting official offices on official business. There were rumors that Jones sent attractive young women to seduce Guyanese officials, but we have found substantiated evidence of only one such relationship.

Perhaps the hardest thing to quantify in the relationship between Peoples Temple and the Guyana government is what did not happen. The people of Guyana as a whole were unaware there was anything called Jonestown in the Northwest District, because the government did not tell them. Even after the tragedy, people in Guyana had to contact friends and relatives living abroad to find out what had happened in their own country. Peoples Temple imported tons of materials which ordinary Guyanese citizens would not have had access to, because customs officials looked the other way. As I hope my few examples demonstrated, Jonestown functioned as an independent entity because the government did not compel them to abide by the nation’s laws.

* * * * *

As my conclusion, I would like to offer something that sounds as though it should have been my introduction. I am in fact deeply honored to have been invited to speak before you. If I were addressing any other gathering about the relationship of the Guyana government to Peoples Temple, I would conclude by quoting part of the critique which Dr. Rodney once offered. Here, at least, I don’t have to explain who Dr. Rodney was.

In 1979, during a speech at Stanford University, Dr. Rodney gave what he described as a Caribbean perspective on Jonestown. Near his own conclusion, he said, “The establishment of Jonestown was not in the national interest. The people of Guyana would have said that the authoritarian control exercised by the leadership in this settlement over the various individuals, was not compatible with the rules governing the behavior of citizens, all citizens, in the society. If they were serious about certain ideological pronouncements which they were making, they would of course have said that this was not a socialist settlement in the least.”

I agree with Dr. Rodney’s analysis: The agreement to allow a group of Americans to establish a project in such physical, legal and informational isolation from the rest of the country certainly laid the groundwork for Jim Jones’ authoritarianism to grow. Whatever the contributing factors of the actions and non-action by both the U.S. and Guyanese governments, however, I believe it would be a stretch to blame anyone but Jim Jones and his followers for what happened that day in 1978.

It’s discouraging to realize that for most Americans, Guyana is best known as the location of Jonestown, where almost 1000 people died in a mass murder-suicide. I also know, however, that in the longer view of Guyana’s own history, Walter Rodney has had, and will continue to have, a greater, more positive, and certainly longer lasting, impact upon the country than anything related to Peoples Temple. My hope is that more Americans will eventually come to that understanding as well.