(Author’s Note: I am a journalist based in Pittsburgh with an interest in American History and social justice issues. My current project is a documentary that will place Peoples Temple in the context of left-wing political movements of the 1960s. The following article, based on phone interviews with Laura Johnston Kohl, is my first attempt to try and place the experiences of an individual Peoples Temple member within the context of the times, and within the timeline of Peoples Temple itself.

(Special thanks to Laura Johnston Kohl for telling me her story. Also, in no particular order, special thanks to the following who have all taken the time to speak with me and answer some (sometimes very basic) questions: Fielding McGehee, Rebecca Moore, Kathy (Tropp) Barbour, Jim Hougan, and Robert Helms.

If you are a former Peoples Temple member who would be willing to participate in my project, I would love to speak with you. I can be contacted by email: joseph.flatley [at] gmail.com.)

“Nobody gives a shit as long as you don’t become political.”

— Jim Jones

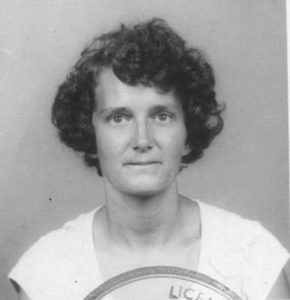

Laura Johnston Kohl was born in Washington, D.C. in 1947, one of “the generation that was most affected by all the catastrophes” of the 1960s and 1970s, she says. Her parents split when she was young, and her childhood was spent living with her mother, her grandmother, and two sisters. Three generations of strong women were living under one roof. Her mother was the breadwinner for the family, and was always politically active. Often, her family would host activists from the deep South while they were in participating in various protests and marches in the capitol. From an early age, growing up in still-segregated Rockville, Maryland, Laura was well aware of the injustice that surrounded her.

Laura Johnston Kohl was born in Washington, D.C. in 1947, one of “the generation that was most affected by all the catastrophes” of the 1960s and 1970s, she says. Her parents split when she was young, and her childhood was spent living with her mother, her grandmother, and two sisters. Three generations of strong women were living under one roof. Her mother was the breadwinner for the family, and was always politically active. Often, her family would host activists from the deep South while they were in participating in various protests and marches in the capitol. From an early age, growing up in still-segregated Rockville, Maryland, Laura was well aware of the injustice that surrounded her.

In contrast to the racist attitudes of many in their community, Laura and her friends did their part for the civil rights movement. “As an integrated group,” she says, “we helped integrate the largest swimming pool in the area, and the amusement park, and we were loud and active.”

After high school, Laura moved on to the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut. This was in 1965, the year of Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society; Operation Rolling Thunder, the joint United States/South Vietnamese aerial bombardment of the north that would last over three years; Selma, Alabama’s Bloody Sunday; and Joan Rivers’ first appearance on The Tonight Show. In Bridgeport, Laura was the president of the Student League for Human Rights, a campus group affiliated with the SDS. Life on the Mason-Dixon line, Laura says, made her “acutely aware that first of all, I was privileged because I was white.”

When Laura left college in 1968, she struggled somewhat in her attempts to carve out a life for herself that was consistent with her anti-racist ideals. Soon she would find herself working for the Connecticut state welfare department by day and hosting the occasional Black Panther meeting in her kitchen at night.

This period of her life was instructive. From the Panthers, she saw the impact that revolutionary social programs could have. Her experience at Woodstock – where 400,000 young people converged for an open-air music festival that became emblematic of a generation – drove home the fact that she had to be around like-minded, politically-motivated people. Woodstock Nation, she says, “that really wasn’t me. It couldn’t be my daily way of living life.”

In early 1970, Laura moved to the West Coast. Upon her arrival in California, she heard “about Jim Jones who had a church, a group up in Redwood Valley, about two hours north” of where she was living with her sister in San Francisco.

“That first Sunday,” Laura says, “we drove up to Redwood Valley and took a look at what was going on in Peoples Temple.”

*****

By 1970, the Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ (to give its full, legally incorporated name) had been in existence for about fifteen years. Jim Jones had been preaching since he was a teenager, and became a student pastor at a Methodist congregation in Indianapolis in 1952. To outside observers – and more importantly, to donors – Peoples Temple might have seemed to be religious at its core, but it’s important to note that this was never quite the case. Jones was ultimately a man who sought temporal power. Growing up in a small Indiana town during the Depression, Jones saw that the church was the one social institution that he could infiltrate, even dominate. His major innovation was to combine the methods of Christian churches with the stubborn socialism that he picked up at an early age from his mother. In 1965, apparently heeding some sort of vision of a nuclear holocaust, Jones moved his congregation to Mendocino County, California.

At first Laura, an atheist since the 10th grade, didn’t feel that she fit in with the members of Peoples Temple. They were “pretty righteous,” she says. “I had been through a lot, I wasn’t quite sure I was ready to suck it up and join what looked like a fairly conservative group.” But Jim Jones knew how to play it — he could be all things to all people. In this case, he appealed to Laura’s activist side.

“Jim was always advocating human rights and civil rights,” Laura says. “Really, from the first time I met him, he talked about it, and that’s what I wanted to hear.” During their first meeting, Jones dropped names. He mentioned farm labor leader Cesar Chavez and American Indian Movement co-founder Dennis Banks, and how he spoke to Angela Davis the night before.

“And he was a genius!” Laura continues. “He memorized the Bible front-to-back, so he could put up a theological argument about anything. He could argue any point. But when you asked him what he really felt, he was not a religious person. But I do think that he used religion to pull people in, and then turn them into activists.”

Much can be learned about a radical group from the way it chooses to communicate its message. Weather Underground, born from the New Left student movement, was known for its communiques. Characteristically, its use of the written word was as insightful as it was clever and irreverent. With Yippies, you need to ponder the meaning of its spectacles, whether that meant raining money onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, running a pig for president, or applying for a permit to magically levitate the Pentagon (Laura was there, by the way; you’ll have to ask her how that particular ritual worked out). The political rhetoric of Jim Jones, which he called “apostolic socialism,” was conveyed during Peoples Temple services. And, most tellingly, his message was imparted through a degree of deception.

“Every service had a political message,” says Laura. In fact, “every conversation had a political message.” Depending on his audience, Jones “would start out with religion, and he’d move it into a socialist message.” In other words, religion was the bait. Politics was the hook.

What eventually brought Laura into the fold was the realization — demonstrated by the dedication of the SDS and the Black Panthers and the “high” she felt from experiencing the collective human energy at Woodstock — that if a better world was possible, “you really couldn’t be a lone voice and have an impact. So the more I went back to Peoples Temple, the more I realized that Jim was really an advocate, and he could be my voice.”

*****

Soon after meeting Jim Jones, Laura moved to Mendocino County, to live and work amongst Temple members. She would remain there until 1977, when she was dispatched to Guyana.

By any measure, the amount of good that Peoples Temple was able to achieve during its California saga is pretty remarkable. San Francisco Examiner religion editor Lester Kinsolving (one of the first, and perhaps loudest — certainly the most obnoxious — of the Temple’s critics) offered an accounting of the group’s holdings in a 1972 article that included a 40-acre children’s home, three convalescent centers, a heroin rehabilitation center, and “in the words of one of the Temple’s three attorneys, ‘our own welfare system.’”

In his book Black and White (later republished as Journey to Nowhere: A New World Tragedy), Shiva Naipaul recounts a conversation with Art Agnos that took place in the aftermath of the Jonestown tragedy. A member of the California State Legislature who would later go on to become mayor of San Francisco, Agnos’ constituents often relied on the charity work of Peoples Temple. If someone in his district lost their welfare check, for instance, “you would send them over to Jim Jones and that day they would be taken care of.

“You’d go in if you were in trouble,” Agnos continued, “if you were in need, and they’d take care of you. No questions asked.” Compared to other social services, those provided by Peoples Temple were of higher quality, and involved none of the proselytizing generally associated with religious social service organizations. (“No tambourines played. No sermons listened to. They just walked in and were seen to…. [a] kind of dignified, good service.”) As it turns out, this was not only good Christian charity — this was an excellent recruiting tool. People would often turn up for the free medical care and, liking what they saw, stay for the Temple services.

Combining elements of the Pentecostal revival and the political rally, we can get an idea of what these services were like, thanks to the group’s efforts to preserve the words and ideas of its leader. After Jonestown, the FBI recovered more than 950 audiotapes from the settlement. Discounting blanks, music, and stuff recorded off the radio, there exists an estimated 600-900 hours of tape documenting Temple life. One particular tape from the summer of 1973 is pretty typical of what Laura would have heard from Jones in this period.

It begins mid-sentence, in the midst of some typical Jim Jones oratory. He’s discussing psychosurgery, experimental brain surgery used for behavior modification. This was being debated in the media at the time as an experimental treatment for extreme cases where psychotherapy, drugs, and electroshock proved ineffective. This type of behaviour modification was also being touted by scientists like of Jose Delgado, author of the 1969 book Physical Control of the Mind: Toward a Psychocivilized Society, as a means of creating a more civilized society — through outfitting everyone with electronic brain implants. (This sort of utopian totalitarianism wasn’t merely a fringe concern. The Gray Lady herself, The New York Times ran an article later that year comparing psychosurgery pioneer Dr. Vernon Mark to “a Clockwork Orange type who carries his patients screaming to surgery, who seeks to develop psychosurgery as a dehumanizing and dictatorial instrument for pacifying and controlling man’s mind.”) It’s really just one small leap of the imagination from this to Jones’ assertion that psychosurgery is part of a program to pacify African Americans

“What they want,” Jones says, “is every black person to go on as a slave. And they’re trying to … alter their behavior so that they will not question the dirty, stenching, smelling ghettos that they’re living in, and they will not quarrel with the fact that they’re making half the wages of the white person, or they will not quarrel with the fact that they’re sent over to Vietnam to fight the rich man’s wars.”

This is the kind of threat, according to Jones, that Peoples Temple must flee America to escape.

“We want to see a Jerusalem, a socialist Jerusalem,” he says. His rap is quasi-socialist, presented in religious language, with some de rigueur sci-fi thrown in. He stumbles over his words a bit, but that’s to be expected when you’re talking off-the-cuff (and probably high as a kite).

“Astronomers,” he continues, “they never have found any heaven. They’ve not found any heaven out there. There’s no bejeweled city of enchanted inertia. No one’s been able to get it on a telescope. No one’s been able to pick up the heavenly choir on any of the radar waves they send out there. Nobody’s been able to pick it up, because it’s not out there.”

Without naming Guyana, he proposes what will become known as Jonestown, “a modern heaven.”

The tape goes on like this for a good seventy-five minutes or so, painting a picture of a country being torn apart by “the Antichrist system,” capitalism, that is the root cause of racism. It’s only a matter of time before Peoples Temple either escapes the United States or faces extermination. In the wake of the 1960s, when the United States government assassinated political leaders home and abroad, the idea that Jones and his followers were next must have seemed wholly plausible.

Looking back, Laura characterizes the 1960s as a time when “the vigilantes just took over,” when radicals and genuine reformers were under the gun. “It didn’t matter who was legally or constitutionally elected,” she says, “they’re going to just get rid of anybody they don’t like. So in that decade, along that ten year span, John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, so many others were killed. For me, in a way, that set my tone.” It was a tone of defiance.

“I wasn’t going to sit passively by,” she says.

For Laura and her fellow members of Peoples Temple, this defiance took the form of both separating themselves from the dominant racist society and doing their part to aid its victims. This was not only in the tradition of the ethical mandate of the New Testament, it had clear parallels to the Survival Programs of the Black Panther Party. They might have been taking a page from Huey Newton’s autobiography, Revolutionary Suicide.

During her time in Northern California, Laura held down a job with the state welfare department while filling any number of roles in the Temple during her off hours. In fact, like everyone else at the Temple, she didn’t really have off hours. Laura was a member of the Planning Commission, the committee that worked closely with Jones to run Peoples Temple. She was also one of the drivers in the fleet of coach buses that the group used for its periodic trips across the United States, sometimes venturing into Canada or Mexico. She tackled various administrative tasks, and was at different times the head of a couple of the group’s communes. This was all in addition to attending Temple services and meetings several times a week.

The long hours were to be expected. After all, despite the fact that Jones wore a clerical collar and appended “Reverend” to his name, Peoples Temple was a radical, revolutionary organization. And accordingly, this led to behavior that would have been out-of-place in a conventional Christian church. Sometimes, in order to enforce discipline, a physical punishment might be rendered. Or as in Laura’s case, you might accidentally doze off in a Planning Commission meeting and wake up to find Jim Jones pointing a pistol at you.

This was all part of “the burden of creating a heaven on earth,” Laura writes in her memoir Jonestown Survivor. “I thought that being a revolutionary just had to be hard, and this was hard, so it must be making me a better revolutionary.”

WIth the benefit of hindsight, she now sees this behavior not as revolutionary, but as “emotional abuse.”

*****

Laura received her resident visa for Guyana on April 5, 1977. Rather than live at the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project (Jonestown’s official name), she remained in the capital city of Georgetown, living in the Temple home at 41 Lamaha Gardens. Jonestown was remote — situated in a patch of northwest Guyana, a full twenty-four hours travel from Georgetown — and it was essential to have a base of operations in the capital. The home had a ham radio for maintaining communication between Jonestown and San Francisco, accommodations for Peoples Temple members arriving from the United States, and according the book Raven by Tim Reiterman and John Jacobs, boasted a “tastefully simple” living room “with hardwood floors, throw rugs, a couch,” and a stereo with “a good selection of jazz and popular music” for entertaining Guyanese government officials. The settlement, which would never see self-sufficiency, depended on a steady flow of provisions. And in order to insure a steady flow of provisions, the government had to be kept happy. This allowed Laura to do her job, procuring food and supplies and sending them off to Jonestown aboard one of the Temple’s two boats, Cudjoe.

“I really did everything,” Laura says. “I was going to the abattoir and getting sides of beef and pigs, I was going out to different parts of Georgetown and getting coconuts and pineapples… I’d buy mostly food and equipment parts for machinery in Jonestown, and clothing, and supplies that we’d need, and then I worked with people coming in and helped them get their paperwork and everything [else] together.”

Then, after about a year living in Georgetown, Laura had sex with a pharmacist she met in the city — a violation of Temple rules. When Jones found out, she was sent to live in Jonestown.

“As soon as I got to Jonestown,” she writes in her memoir, “I was called up front at a public meeting. Jim told me he was disappointed in me, and said, ‘I should have slept with you myself.’ I do remember cringing at that thought.” Then, after some token roughing up — “a couple of people slapped me” — Laura received her sentence: assignment to the Public Services Crew, also called the Learning Crew (because you were sent there to be taught a lesson). This was probably the least of the punishments doled out in Jonestown. For other offenders there could be more serious consequences, reportedly involving snakes, drugs, and something called “the box,” a six-by-four foot underground cell.

For Laura, her love of Guyana and the whole Peoples Temple project was so great — and she was kept busy enough — that this uglier side of Jonestown sort of faded into the background. Working on an agricultural crew meant that, long hours aside, she was working to feed herself and other Temple members. It was important, dignified work, and that took the sting out of the discipline. Soon, in addition to toiling in the fields, she would teach Spanish at night, work in the law office, and take on other jobs around the settlement.

“You know,” she says, “I loved it. I would never have left. We had 1,000 people living in the middle of a rainforest, and we were feeding everybody three meals a day,” despite the fact that poor growing conditions and primitive conditions made it a constant struggle to find enough food for everyone. “And we had a free medical clinic, and we had this awesome community that was multi-racial, multi-educational level, just everything. It was my dream community. And I felt that we were at the very beginning, like pioneers. And the part of it that was difficult, we’d get over it, and we’d be able to fix everything that’s wrong with it.”

This was where things stood in October of 1978, when Jones sent Laura back to Georgetown.

At this point, Jim Jones “knew the clouds were coming over,” Laura says. He was convinced the upcoming visit from Congressman Leo Ryan would mean the end of the Temple, that it would mean the end of Jones. Looking back, Laura says that she believes Jones “sent me back into Georgetown to take up my old job, so that some people who were in Georgetown could go back into Jonestown with their loved ones. So that’s how I ended up not being in Jonestown on November 18.”

*****

A total of 918 people died in Jonestown, at the nearby airstrip in Port Kaituma, and in Georgetown on November 18, 1978. It was either luck or a glitch in Jones’ plan that spared Laura.

The tragedy, really, was manifold. First, there was the tragic loss of life. But also there was the manner of death — a murder-suicide that belied the utopian dream that Peoples Temple members worked so hard for. It was an ignominious end, orchestrated by Jones, that not only took his followers’ lives but made a mockery of their ideals as well.

“I think that anybody who went to Guyana, anyone who made the choice to participate in Peoples Temple and be in Guyana, had a dream that we could create a community that would show people, you could live in a harmonious society without racism or without sexism, where everybody would be taken care of properly and treated with dignity. We thought that was possible in Peoples Temple.” But in the end, she says, “Jim disintegrated and took everything with him.”

That explains what happened, but it doesn’t explain the vast disconnect between the aims and desires of the Peoples Temple membership — left wing, anti-fascist, anti-racist, determined against all odds to embody the very highest of ideals — and the self-destructive psychopathology of Jim Jones. With hindsight, it becomes clear that for someone like Jones, ideals are really only one part of a system of control. Laura experienced this firsthand.

Jones, she says, “surrounded himself with determined and dedicated people who loved his message. Maybe not his behavior, but they loved his message. And so, as he became more and more paranoid and mentally ill,” the small group of people that were closest to Jones, and privy to his plans for revolutionary suicide, “they could see him falling apart, but they just totally enabled him. Kind of like battered wives or something like that. Even as he was falling apart, they just picked it up.”

The apotheosis of this relationship between Jones, his inner circle, and the complex social system of the Jonestown community was the mass murder-suicide of November 18.

“He was completely incoherent,” says Laura, “and yet [his closest followers] put out the poison, they started poisoning the children, they made sure everybody knew where things were, they had it all organized. I mean, everything that was going on — Jim was not doing any of that. He had delegated it to people who, you know, somehow bought his insanity and internalized it and became as insane as he was.”

This process has been described in some detail by Marc Galanter, Professor of Psychiatry at the NYU School of Medicine and the editor of the American Psychiatric Association’s report on cults and new religious movements. The dynamic of a group like Peoples Temple, he writes, can “create psychiatric symptoms in people with no history of mental disorder or psychological instability…. In essence, an effective cult is able to engage and transform individuals in ways that disrupt an otherwise-stable psychological condition, in many cases causing significant guilt and resulting in a severe psychiatric reaction.”

For those who survived, whether because they were in Georgetown, the United States, or out hiding in the jungle somewhere, the beliefs that brought them to Jones would undergo a brutal reassessment.

“I think that we all became very cynical after that,” Laura says. “In a sense, it turned all of us from idealists into cynics and people who are just really angry that, you know, we were in that situation. And I mean, it’s just stupid! With all the signs that we can look back and see now, how stupid was I to think, ‘Oh, no, Jim’s different?’ That’s, like, so absurd, ludicrous. There were so many clues. Why didn’t I see it?”

In the aftermath of Jonestown, Laura was determined to save something of her old self, to claim some piece of herself that not even Jim Jones could destroy. “I salvaged being an activist,” she says. “I have not become less political, but I have become less mesmerized by any words somebody says. I want to see the works that are done. If they’re not doing it so that I can see it, I’m not going to believe it. So I mean, I think that’s the result. The result is that I don’t trust anybody to be as good as their word. They’re only as good as their acts.”

But what about the original vision, the dream that Laura and her fellow members of Peoples Temple shared? I asked Laura if she sees anyone keeping that dream alive today.

“No,” she answers. Then a long pause hangs in the air. “There are bright spots here and there,” she continues, “and then there’s just insanity and meanness and racism in pandemic. So I don’t see it around. That’s why we have to work so hard.”

Ultimately, the Peoples Temple story is a cautionary tale for those who would place their trust in any organization – or for that matter, a government – that does not tolerate dissent.

“Things can never be so good that you can close your eyes and turn off your critical thinking,” Laura cautions. “There’s never anything that is so absolutely perfect that it doesn’t need course direction and careful guidance. Not any politician that you worship, not any belief, not any event, there’s not anything in life that is so perfect that you can close your eyes and just go on faith. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing.”

(Joseph L. Flatley is a freelance journalist and video producer based in Pittsburgh. A selection of his work is available on his website, http://lennyflatley.net.)