The 1978 discovery of nine-hundred-and-eighteen bodies at the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project (Jonestown), Guyana, registered as a baffling act of violence for media viewers across the globe. Its legacy in the psyche of the twenty-first century must thus be a reckoning with the supposed absurdity and hysteria of the namesake founder, Reverend Jim Jones, and the Americans who joined him in “revolutionary suicide.” Conclusions are likewise difficult for the former members of Peoples Temple as evidenced in survivor Tim Carter’s essay, “Thirty Years Later,” the summation of his reflections on the relevant questions: how did “common folk … and the [ordinary individuals] who comprised the faces of America” permit the manipulation and gradual restriction of their lives in a build-up towards their demise (Carter)? Is it natural or fatuous to frame the victims as “mindless sheep” who “drank the [cyanide laced] Kool-Aid?” And perhaps more sensitively, were they victims of mass murder or practitioners of mass suicide?

Carter’s memory and narrative places responsibility on perpetrator and victim alike, though he argues that far from an abstraction of anomalous insanity, the behavior of Peoples Temple finds precedent in the “millions … tortured and slaughtered in the name of ‘God’” and mankind’s fascination with “higher causes” (Carter). He goes further and links the more recent USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 and its suspension of rights as a relevant continuation of this behavior in what most would consider a civilization anathema to the barbarity of Jonestown. Collectively, these connections are purposed to prevent Peoples Temple from being “eroded into [nothing more than] a distant and unpleasant aberrant memory,” perhaps even realizing for the contemporary world the relevance and lessons from Jonestown that are “universal in nature and application” for “humankind’s … psycho-social dynamic” (Carter). It is a reward both public and private for the survivors of Peoples Temple in its potential to transform Jonestown into a meaningful memory, granting them a measure of peace through the ennoblement of their loss.

Yet can the knowledge and imagery of violence against human life achieve Carter’s hopes in the modern psyche?

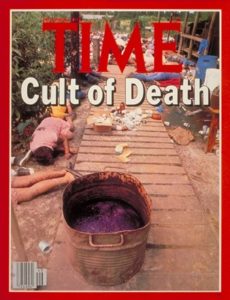

The public’s narrative on Jonestown during its immediate aftermath is well-preserved in David Hume Kennerly’s photograph for Time Magazine’s cover story in its December 4th 1978 issue. Peoples Temple is classified as nothing short of a “Cult of Death,” the connotative diction of which is unequivocal in condemning the Temple as an empathetically inaccessible and hysterical sect, the motivations and behavior of which cannot be understood as “universal in nature [or] application” (Time; Carter). Even with the input of professional theories from psychiatrists and other experts, the news of Jonestown remained “fearsomely fascinating and ultimately inexplicable” (Time). It can thus be argued that the public memory did not follow Carter’s narrative in its suggestion that the tragedy at Jonestown was an exercise – albeit the most extreme in recent years – of a common societal flaw. Instead, the memory of Peoples Temple has been held at arm’s length as an unholy spectacle of inhuman aberration.

This differentiation in narratives between survivor and the onlooking public can be rationalized through renowned art critic and writer John Berger’s 1972 essay, “Photographs of Agony.” Referencing the photograph captured by Donald McCullin depicting an “old man squatting with a[n injured and bleeding] child,” Berger questions the evocative power such photography might possess (Berger 212). His central position drives towards debunking notions that the imagery of horror – namely the photography of the Vietnam War – can inspire meaningful reflection. Nor are the images there to feed an imagined public desire to be “shown the truth” or increase the sensationalist imagery of violence to a public “inured” to graphic horrors (Berger 212). Instead, explicit photography endures in public media by virtue of not achieving the influence of change over the public psyche or inspiring lasting concern within it.

Any claim to that power is immediately compromised as the “original” narrative of whatever it is that occurred is not transferred or truly captured in the lenses of photography. Instead, Berger asserts that the word “trigger” applies in equal effect to “rifle and camera” through the latter’s “doubly violent” effect of isolating a moment already isolated by merit of its extraordinary suffering (Berger 213). The images of the Vietnamese father and the field of corpses at Jonestown must speak to the imagination of viewers who simply have not experienced the pains and losses felt by individuals like Carter. This issue is made more acute if the original narrative is distinguished from any conception of a definitively “true” version of events, but rather the narrative built on the subjective reception of those who were there, a reception that cannot be truly re-lived in its entirety by even the person to which it belonged. Thus, violence is dealt to the memory of the tragic day in 1978 in addition to the bodies of those who died.

The problem can be reduced to a self-evident reality: photographs are silent. They do not literally speak through sound or written word. Though some would dress photography with that power – referencing the potency and shock that images can indeed invoke – it must be recognized that the voice in those instances sounds from within the eye and mind of viewers. This mechanism is central to the viewing of Kennerly’s photograph, particularly with his decision to place an empty vat of Kool-Aid as the central device of his image. The subject is a benign drink consumed daily by millions across the world, yet here it is associated with the imagery and knowledge of death that encircles it on Time’s cover. Comprehending this otherwise perplexing association depends on the imagination and logic of viewers being imposed over any true narrative the image is presumed to have.

In this manner, the “why” concerning the events within the photograph is absent, a serious problem concerning photography’s central role in communicating the Jonestown tragedy not experienced by the majority. The process of rationalization must thus come from viewers; the sensory media that seeks to capture the imagery of horror at Jonestown possesses no narrative that can be considered self-evident.

Concordantly, Berger suggests that the commonly-touted notion that “such photographs [of tragedies that] remind us shockingly of … the lived reality … behind the abstractions of politically theory, casualty statistics or news bulletins” cannot be accepted (Berger 212). He underlines that the Sunday Time publishes violent imagery from the Vietnam War and from The Troubles of Ireland, despite the outlet’s support for policies driving that violence. Requisitely, it can be suggested that those images do not intrinsically command all who view them to curse the causes of that violence (Berger 212). Likewise, the imagery of “revolutionary suicide” does not inherently horrify viewers into thought and action concerning the perils of group think as hoped for in Carter’s narrative. By contrast, it is the absence of that narrative, and any other rational narrative, that promotes the use of Jonestown imagery across the covers of many headlines; the mystery and absurdity builds a strong attraction for viewers.

Yet if the photograph is silent, can the shock of its absurdity galvanize the creation of a narrative – from within viewers – that is receptive to the Jonestown legacy promoted by Carter? There is no denying that the photographed moment possesses power. Berger characterizes its effect as nothing short of “arresting,” capable of creating a discontinuity of time between the shock of the photographed world and the viewer’s naturally tamer immediate reality (Berger 213). Instead of inspiring concern, however, Berger suggests that a viewer may instead become conscious of this discontinuity, perhaps psychologically processing it as “his own personal moral inadequacy” in his inability to transfer the shock of the photograph to his own life (Berger 213). Such a reflection may border on an existential challenge to a person’s desire to treat oneself as morally just – how can one react but with guilt in the face of his or her own inability to respect the pain of others as a concern on par with the real of their own lives?

The psychological reaction to this challenge drives towards the removal of that moral existential question. Berger suggests that a viewer might “perform a kind of penance” through the act of donating a paltry sum to charities such as Oxfam or UNICEF to dispel their guilt (Berger 213). Its effect is altogether dangerous as the action makes no move to tackle the photographed agony and yet concludes with the viewer’s conscience cleansed. The same effect might be observed at any point of the modern world given the widely reported conflicts and crises throughout the Middle East and Africa – namely through the inaction of even those who are morally affected and concerned. Yet even this minimalistic reaction may not be applicable to Jonestown as viewers have trouble processing the moral implications of Peoples Temple in relation to themselves, possessing little empathy with those they presume to be “whacko cultists” (Carter).

That presumption covers the issue with a misguided illusion of normalcy. After all, mad groups presumably perform mad deeds. As suggested by Berger, viewers will seek to accept that the perceived differences between ostensibly absurd acts and their own behavior are “only too familiar” and to be expected (Berger 213). It is a narrative that contributes to the preservation of the viewers’ self-perception as a sane population above such “madness” by relieving them of the need to accept that individuals “that are the faces of America” – and by extension they themselves – might have been responsible for such a tragedy (Carter). It is an inadvertent act of intellectual violence against the narrative of Carter, a narrative held by many survivors of Peoples Temple.

Thus, the narrative that might have best reflected the seconds, minutes, or hours of the tragedy at Guyana suffers a swift death despite the intervention of the camera – or of any other medium. The framing of Peoples Temple, their scapegoating as anomalous practitioners of absurd behavior, preserves a narrative built to enshrine the supposed civility and sanity of the modern world. It is a blockade that Carter and any Jonestown warning on the perils of “group think” are not likely to overcome.

Works Cited

Berger, John. “Photographs of Agony.” The Broadview Anthology of Expository Prose. Buzzard, Laura. LePan, Don. Ruddock, Nora. Stuart, Alexandria. Broadview Press, 2016. Ontorio, Canada. 211-214.

Carter, Tim. “Thirty Years Later.” Accessed 28th March 2017.

Kennerly, David Hume. Cult of Death. 1978. Photograph. Time Magazine, New York. Time. Web. Accessed 28th March 2017.

McCullin, Don. Hue. 1968. Photograph. Traces of the Real. Web. Accessed 28th March 2017.

(Ian Chen is originally from a small port in Taiwan and has since lived internationally for many years and derives his interests from a diversity of cultures. He is currently a history major at the New York University. He can be reached at ic910@nyu.edu.)