Black lesbian poet and activist Audre Lourde once said, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” Lourde was one of the most fiercely eloquent champions of the revolutionary right of black women to witness and speak their truths in resistance to silence.

Her words resonate deeply as the fortieth anniversary of the Jonestown massacre approaches. Black women lived, loved, struggled, and died in disproportionate numbers if Jonestown. Their belief in the revolutionary promise of the settlement was a testament to their long legacy of activism and organizing in the face of erasure. Renewed public interest in the tragedy will no doubt elicit another round of questions about the Peoples Temple community, its politics, and its status as a historical “curiosity.”

In an effort to counter the marginalization of black women in these spaces, I have tried to bring black voices to the page, stage, and screen, through adaptations of my novel White Nights, Black Paradise. As a piece of speculative fiction, White Nights, Black Paradise sets out to trouble the boundaries between fact and fiction in order to expose how myths about Jonestown were constructed over time through multiple interpretations, voices, and memories. Throughout the adaptation process, I have been acutely aware of the ways in which black experiences in Jonestown are often appropriated for mainstream consumption, and how they are taken out of context and depoliticized. In an era in which black folk continue to struggle with the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, and racialized sexual violence, the prevailing narrative of hoodwinked black women without agency has become an insidious cliché.

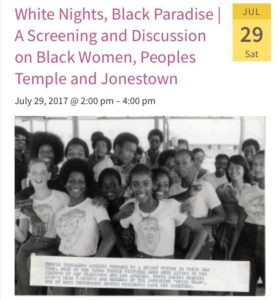

In response to these issues, I organized a black women survivors’ panel discussion at San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora this summer in conjunction with the screening of my short film on White Nights, Black Paradise. (A trailer for the film itself appears here.) The panel featured Leslie Wagner Wilson, Jordan Vilchez, Yulanda Williams, and Rebecca Moore. The packed audience included at least eight other former members of the Peoples Temple community from the Bay Area and elsewhere. A 15-minute segment of the two-hour panel discussion appears both here and here.

In response to these issues, I organized a black women survivors’ panel discussion at San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora this summer in conjunction with the screening of my short film on White Nights, Black Paradise. (A trailer for the film itself appears here.) The panel featured Leslie Wagner Wilson, Jordan Vilchez, Yulanda Williams, and Rebecca Moore. The packed audience included at least eight other former members of the Peoples Temple community from the Bay Area and elsewhere. A 15-minute segment of the two-hour panel discussion appears both here and here.

Building on the film’s themes, the panel was designed to elevate black women’s experiences and stories. Leslie’s powerful book Slavery of Faith chronicles her life in Peoples Temple and her dramatic escape from Jonestown hours before the 1978 massacre. Jordan and Yulanda were both involved with the Temple at a young age, and although both had gone to Guyana, neither were in Jonestown on that final day. Rebecca, the only white woman on the panel, lost three family members at Jonestown; she has published several books about the Temple and Jonestown, and has of course been instrumental in developing and promoting culturally responsive Jonestown scholarship via this site.

The discussion ranged from the women’s personal accounts of being in Jonestown to the internal divisions that belied the movement’s veneer of multiracial harmony. Both Leslie and I have critiqued the racial and gender hierarchy that existed in the movement’s leadership, and the degree to which Jones’ white women lieutenants were complicit in its escalating climate of intimidation, abuse, and harassment. During one exchange, Leslie and Yulanda took issue with Rebecca’s characterization of power and authority in Jonestown. While Leslie and Yulanda recalled that African American members had little official authority in Jonestown, Rebecca made reference to the diverse work assignments that black folks fulfilled. Leslie and Yulanda vividly recalled the harsh living conditions in Jonestown and compared it to being in a slave camp. What came through most powerfully in these exchanges was the differing “class” positions Jonestown members had within the compound’s power structure, with younger white women being the most privileged and favored. Leslie and Yulanda also emphasized the pivotal role Jones’ whiteness played in eliciting support and adulation in the black community.

The discussion ranged from the women’s personal accounts of being in Jonestown to the internal divisions that belied the movement’s veneer of multiracial harmony. Both Leslie and I have critiqued the racial and gender hierarchy that existed in the movement’s leadership, and the degree to which Jones’ white women lieutenants were complicit in its escalating climate of intimidation, abuse, and harassment. During one exchange, Leslie and Yulanda took issue with Rebecca’s characterization of power and authority in Jonestown. While Leslie and Yulanda recalled that African American members had little official authority in Jonestown, Rebecca made reference to the diverse work assignments that black folks fulfilled. Leslie and Yulanda vividly recalled the harsh living conditions in Jonestown and compared it to being in a slave camp. What came through most powerfully in these exchanges was the differing “class” positions Jonestown members had within the compound’s power structure, with younger white women being the most privileged and favored. Leslie and Yulanda also emphasized the pivotal role Jones’ whiteness played in eliciting support and adulation in the black community.

As I have argued in previous articles, Jones’ minstrel-like ability to evoke both white savior-hood and black nationalism – in order to appeal to African Americans – is a familiar theme in American politics and pop culture. Some on the panel likened Jones’ appeal to that of the charismatic, benevolent white Jesus figure force fed to blacks under slavery. Panelists also highlighted Jones’ status as a power broker in the Bay Area political establishment, emphasizing how this made public officials more willing to cosign the Temple’s activities, despite widespread allegations of abuse and exploitation within the church. Some of this abuse and exploitation was directed toward LGBTQ members of the church due to Jones’ internalized homophobia (he often went on homophobic tirades, yet engaged in sex with men). As moderator, I contextualized the way in which the African American community of Fillmore was primed to embrace Jones’ “radical” social gospel ethos in light of poverty, job discrimination, violence perpetrated by the state, and the mass displacements that rocked Fillmore as a result of the region’s “urban renewal” regime.

Why did it take nearly forty years for this kind of discussion to take place? The comments we received after the event indicated that there is high interest in the rich social history of black Jonestown. One audience member commented that they were moved by “the courage, power and heartfelt words of wisdom, and that [they] did not know the majority of membership were black women.” Another related that they were interested in “the hierarchy of the Jonestown system [and] was so honored to hear survivors,” while being “unaware of the escapees & survivors [thinking] all had perished.”

These comments underscore the need for more black feminist literary and scholarly appraisals of the black diasporic experience in Jonestown vis-à-vis religion, black women’s self-determination, and the event’s contemporary significance. In adapting White Nights, Black Paradise as a stage play, I hope to extend the conversation.

The play brings the media construction of Jonestown narratives into greater focus—foregrounding the divide between the lived experiences, dreams, ambitions, and politics of its black women protagonists and mainstream fascination with the “perversity” of the massacre. The play opens with the character of a night watchwoman at the Dover Delaware Air Force Base – the military morgue where the bodies of Jonestown victims were shipped after the massacre – banging on an old TV as the sound of a newscast about the event echoes overhead. The banging is an allusion to the throwback practice of hitting old TVs to get a clearer picture.

The distorted cultural picture that the public has been provided of Jonestown and Peoples Temple is a recurring theme throughout the play, which is presided over by a Greek chorus of black women who give commentary on the play’s events. The chorus is critical to the play’s meta-analysis of the invisibility of black women’s lives, voices, and social histories in the popular imagination of Jonestown. It is also an artistic device that seeks to problematize reductive notions of black female selfhood, identity, and religious ideology; for example, throughout the play the chorus critiques organized religion and respectability politics. In the play, as in the book, the fictional character of black activist journalist Ida Lassiter pursues an “investigation” into the Temple’s dealings and becomes personally embroiled in relationships with Jones, other Temple members, and the black press. As a once-revered independent journalist, Lassiter represents the ambivalent relationship the black and mainstream press had with Peoples Temple and Jim Jones. Although the real life African American activist/publisher and physician Dr. Carlton Goodlett bankrolled the Peoples Forum, there has been little exploration of the black press’ role in either promoting or critiquing Peoples Temple pre-Jonestown. Hence, I was interested in exploring the political influence the (critical) black press had on the movement, highlighting tensions between Lassiter and Hampton Goodwin, the Carlton Goodlett character. The mass removals in the Fillmore community, and the socioeconomic challenges confronting African Americans during the post civil rights and black power eras, also take center stage in the play.

Ultimately, it is my hope that these artistic explorations lead to more platforms for survivors and scholars of color—in resistance to the white gaze “crunch[ing] us into other peoples’ fantasies.”

(A trailer for Sikivu Hutchinson’s short film, White Nights, Black Paradise, appears on Vimeo. The film itself was screened on March 24, 2017, at an African American Women in Cinema Film Festival screening in New York City.

(The first staged reading of her play adaptation White Nights, Black Paradise, will be on December 14th in Los Angeles.

(Sikivu Hutchinson is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. Her complete writings for the site are here. She may be reached at shutch2396@aol.com.)