Cenotaphs all to the fallen 918 Peoples Temple congregation members of Reverend James Jones, each utterance of that darkest idiom, Drink the Kool-Aid, offers one a locus of sorrowful contemplation. Preserved immortal within contemporary American vernacular, the infamous, gallows-humoured phrase of course denotes both our fatal susceptibilities to society’s expectations, as well as our fanatical adherences, to equally fatal endeavours.

That very same darkest idiom then would prove wholly catalytic to the authoring of Welcome To Jonestown, a mixed-medium collaboration between Australian illustrator Lars Wannop, and New Zealand writer, Kingston Trinder. An enigmatic utterance when first encountered, one’s mind is immediately drawn back across the vast, clouded plains of collective memory, to Indianapolis, Indiana, where Jones established his original congregation, the Community Unity Church in 1954, later to be known as the Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church; then onward to Redwood Valley in northern California in 1965, where Jones would attempt to establish a racially-integrated socialist utopia, before journeying southward to San Francisco. And now, lastly, to faraway Guyana in 1974, a former British colony upon South America’s northeastern Caribbean coast. Here, upon some 3,824, wholly outlying, thickest jungle acres, Jones would establish an experimental cooperative constituted by hundreds of American and Guyanese devotees, The Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, better known as Jonestown.

Coloured With Kool-Aid

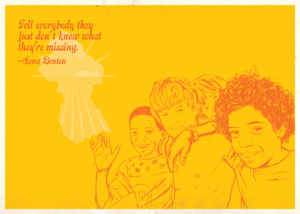

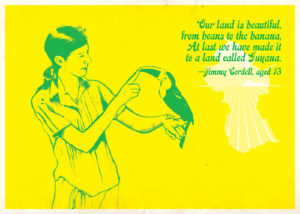

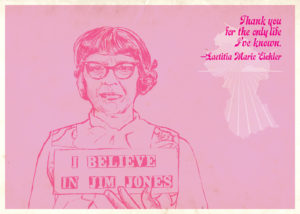

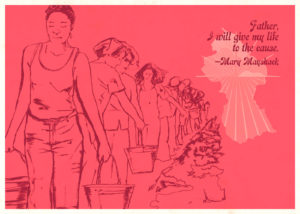

Welcome To Jonestown’s six chromatic postcards draw aesthetic and format from characteristic QSL cards. Written and mailed confirmations of received radio communication between amateur radio stations, such as the two operated by Peoples Temple members from Georgetown, Guyana’s capital, WB6MNH/8R1, and Jonestown itself, WB6MID/8R3, or confirmation of a two-way radio communication with an external listener – typically amateur radio enthusiasts and hobbyists, seeking unfamiliar contacts – such QSL cards are of characteristic postcard format. Augmented with authentic contemporary Guyanese postal stamps and postmarkings, original addresses and recipients, Wannop observes, “Jonestown, as a dystopian tragedy constituted by darkest turning events lead itself naturally to creating a bright to ever-darkening colour scheme. Our discovery that grape flavoured Kool-Aid was the flavour within which the cyanide was mixed, lent me the idea to employ the colours of the 6 original flavours of Kool-Aid as the chromatic theme of the 6 postcards, reflecting that optimistic arrival within Guyana, to the fateful day of November 18th.” “Such darkening flavours and colours also serve as an illustrative microcosm for the progressive disillusionment, despair, delirium and resignation that characterised many Peoples Temple members’ experiences within Jonestown,” Trinder appends. “Dawning Jonestown went accompanied by such indefatigable optimism, such palpable elation. And yet, as time passed by, Jones’ sanity progressively declining throughout, what was once incandescent, utopian joy, gave forth away at last, for many, to wholly unimaginable agony, embitterment, and fear.”

Forgotten Visions Of Guyana

Wannop’s quietly eclipsing illustrations are gathered from the vast archive of images and ephemera captured from within Jonestown by Peoples Temple members and leaders. Largely neglected perhaps in favour of more macabre, more emblematic, familiar images captured by photojournalists of Jonestown’s dead, Wannop believes, “these more intimate, personal images, so very well documented before that November’s day, were the images I found the most fascinating and surprising. A young woman holding an amicable toucan; children tenderly grasping one another about the shoulders; Larry Schacht, the doctor commissioned by Jones to make tests with cyanide, gazing through a microscope; an elderly African-American woman presenting a cut-and-paste ‘I believe in Jim Jones’ handbill. These images all left an immense impression upon my mind, images that demanded to be illustrated.”

Wannop’s quietly eclipsing illustrations are gathered from the vast archive of images and ephemera captured from within Jonestown by Peoples Temple members and leaders. Largely neglected perhaps in favour of more macabre, more emblematic, familiar images captured by photojournalists of Jonestown’s dead, Wannop believes, “these more intimate, personal images, so very well documented before that November’s day, were the images I found the most fascinating and surprising. A young woman holding an amicable toucan; children tenderly grasping one another about the shoulders; Larry Schacht, the doctor commissioned by Jones to make tests with cyanide, gazing through a microscope; an elderly African-American woman presenting a cut-and-paste ‘I believe in Jim Jones’ handbill. These images all left an immense impression upon my mind, images that demanded to be illustrated.”

Assembling such images proved equally fascinating both to Wannop and Trinder, authoring together a disarming cacophony of images, graphic elements and words, “to present numerous secrets side-by-side,” as Wannop observes, “as if they were two wholly unintelligible languages comprehensible only after the beleaguered ship had, so to speak, now sunk.” Juxtaposing Wannop’s increasingly mournful compositions with the original Peoples Temple quotations gathered by Trinder, such sought to reveal that ever-widening chasm between Peoples Temple members’ experiences, projected as emphatically transcendent to members yet to arrive within Guyana. “Ceaseless sunshine, tropical fruits and plentiful vegetables, fantastically exotic birds, reptiles, tapirs, and wildflowers, tangerine dusks and joyous dawns, Jonestown,” Trinder observes, “went proselytized to all as a faraway Arcadian jungle sanctuary, wholly removed from the inequities and trespasses of modern life. Yet such projected impressions obfuscated the ominous-clouding experiences of Temple life deep within the Guyanese jungle. I wanted to reveal both the illusory nature of these almost propagandistic images, as well as illuminate omissions from more orthodox Jonestown narratives.”

Assembling such images proved equally fascinating both to Wannop and Trinder, authoring together a disarming cacophony of images, graphic elements and words, “to present numerous secrets side-by-side,” as Wannop observes, “as if they were two wholly unintelligible languages comprehensible only after the beleaguered ship had, so to speak, now sunk.” Juxtaposing Wannop’s increasingly mournful compositions with the original Peoples Temple quotations gathered by Trinder, such sought to reveal that ever-widening chasm between Peoples Temple members’ experiences, projected as emphatically transcendent to members yet to arrive within Guyana. “Ceaseless sunshine, tropical fruits and plentiful vegetables, fantastically exotic birds, reptiles, tapirs, and wildflowers, tangerine dusks and joyous dawns, Jonestown,” Trinder observes, “went proselytized to all as a faraway Arcadian jungle sanctuary, wholly removed from the inequities and trespasses of modern life. Yet such projected impressions obfuscated the ominous-clouding experiences of Temple life deep within the Guyanese jungle. I wanted to reveal both the illusory nature of these almost propagandistic images, as well as illuminate omissions from more orthodox Jonestown narratives.”

Voices From Peoples Temple

Drawn from the original correspondences of Peoples Temple congregation members from within Jonestown to fellow Temple members, kinfolk and companions then remaining within America, such are assembled chronologically. Unravelling a harrowing, fateful narrative through the fracturing words of Temple members themselves, one glances deep within the unexamined collective consciousness of Jonestown’s deteriorating inhabitants, as well as that of Reverend Jim Jones himself, now wholly consumed by messianic illusion. “Father has provided an amazing community for us. We have suffered an unimaginable sort of harassment in the United States. And then Jim would just start laughing and clapping his hands. Cyanide is one of the most rapidly acting poisons. Jonestown’s narrative,” Trinder contemplates, “remains a complex one, characterised less by merely Temple members’ slavish adherence to an illusory faith, and a maniacal figure. But rather one within which many of the profound aspirations, ideologies, dreams and visions, we as a species universally possess, finds most heartrending expression.” For Wannop, Temple members’ correspondence from Jonestown “demanded a visual contrast. All the source images chosen were carefully selected to offset the ‘Wish you were here’ nature of members’ quotations, with each imparting further meaning, hidden or unexpected truth to the accompanying texts. Carl Hall’s ‘I have no plans as far as dying’ matched so very ominously with the counter-balance of Larry Schacht’s meticulous, cyanide-researching endeavours upon the postcard’s reverse. Each image appears inconceivable, improbable even with retrospect. Surely more Temple Members must have seen the end coming, but how many knew it was too late? And how many wilfully sought to ignore that truth?”

Drawn from the original correspondences of Peoples Temple congregation members from within Jonestown to fellow Temple members, kinfolk and companions then remaining within America, such are assembled chronologically. Unravelling a harrowing, fateful narrative through the fracturing words of Temple members themselves, one glances deep within the unexamined collective consciousness of Jonestown’s deteriorating inhabitants, as well as that of Reverend Jim Jones himself, now wholly consumed by messianic illusion. “Father has provided an amazing community for us. We have suffered an unimaginable sort of harassment in the United States. And then Jim would just start laughing and clapping his hands. Cyanide is one of the most rapidly acting poisons. Jonestown’s narrative,” Trinder contemplates, “remains a complex one, characterised less by merely Temple members’ slavish adherence to an illusory faith, and a maniacal figure. But rather one within which many of the profound aspirations, ideologies, dreams and visions, we as a species universally possess, finds most heartrending expression.” For Wannop, Temple members’ correspondence from Jonestown “demanded a visual contrast. All the source images chosen were carefully selected to offset the ‘Wish you were here’ nature of members’ quotations, with each imparting further meaning, hidden or unexpected truth to the accompanying texts. Carl Hall’s ‘I have no plans as far as dying’ matched so very ominously with the counter-balance of Larry Schacht’s meticulous, cyanide-researching endeavours upon the postcard’s reverse. Each image appears inconceivable, improbable even with retrospect. Surely more Temple Members must have seen the end coming, but how many knew it was too late? And how many wilfully sought to ignore that truth?”

Where Salvation Lies Interred

Cenotaphs all our darkest, gallows-hued Kool-Aid utterances may remain, such attest further to the enduring notion of Jonestown as an allegorical narrative; one that forever admonishes against the excesses of idolatry, the fallacy of saviour, the abandonment of actuality, and the willed myopia of faith. Reverend Jim Jones and the Guyanese jungle sanctuary he and fellow Peoples Temple devotees sought to establish is however, less an unequivocal synonym of millenarian fanaticism, centred about a messianic charlatan. Elements of such are of course encompassed within Jonestown’s wretched narrative, however what the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project truly remains more illustrative of, is our species unwavering rapture for, and necessity of, assured salvation. Witnessed by millennia past, ceaselessly we seek redemption, transcendence, and eternity, cyclically possessed of the conviction that beyond our torturous terrestrial existences lays another; one fundamentally altruistic, beatific, and magnificent, absent of all the suffering, trespasses and fears of our besieged world. Jonestown of course remains illustrative of our enduring fanaticism for salvation. Yet what endures perhaps most despairing of all, aside the anguished, unnecessary deaths of 918 men, women and children, is not necessarily how and why such a cataclysm occurred, but rather, the massed deaths of our own ideologies and beliefs. And that nihilistic disillusionment with which our world was regarded by so very many broken sentient beings, that ensured many possessed then, as many have now, and will forever more, the resolute conviction, that even death, remained favoured over life within our sorrowed world.

“Many of us are now dead. Each moment, another passes over to a peace,” declares Richard Tropp in his plaintive dispatch of November 18, 1978, To Whomever Finds This Note. “These are beautiful people, not afraid. There is quiet as we leave this world. The sky is gray. People file slowly past and take the somewhat bitter drink, many more must drink. I am ready to die now. Darkness settles over Jonestown, on its last day on earth.”

Welcome To Jonestown, a limited edition, six postcard illustration series was exhibited in 2015, within Cash Machine, a group installation curated by FatherSons Gallery, Los Angeles, California.

(Lars Wannop may be reached at lwannop@gmail.com. Kingston Trinder may be reached at hello@kingstontrinder.com.)