(Thomas Mrett is an independent researcher who runs a site for historical simulations called eRegime. His collection of articles for the jonestown report is here. He may be reached at kocotosi@gmail.com.)

Discussions about Jim Jones often note that he referred to himself as a communist, that he dangled the prospect of the residents of Jonestown relocating to the Soviet Union, and that the community’s inhabitants were encouraged to consider themselves Marxist-Leninist revolutionaries.

These facts have led numerous commentators who are hostile to Marxism to denounce Jonestown as an especially sordid example of Marxist theory put into practice.

The purpose of this article is to argue that Jonestown is the outcome, not of Marxism, but of non-Marxist varieties of communist thought which were explicitly criticized by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels under such terms as “utopian socialism” and “crude communism,” contrasting these with what they termed their own “scientific socialism.”

This article is intentionally narrow in scope; I am omitting discussion of religion (including Jones’ use of the Bible to justify communal living and the distribution of products based on need, though this was a frequent feature of utopian socialist/communist thought), the role of Jones as a cult leader, and other subjects that are evidently important to understanding Jones and the eponymous settlement. Nor is this meant to be a detailed analysis of life in Jonestown. Instead it will simply emphasize the utopian features which Marxists argue doom any such settlements to defeat.

This article will begin by explaining the concepts “utopian communism” and “crude communism,” while the remainder will discuss how these terms describe Jonestown.

The Meaning of Utopian Communism

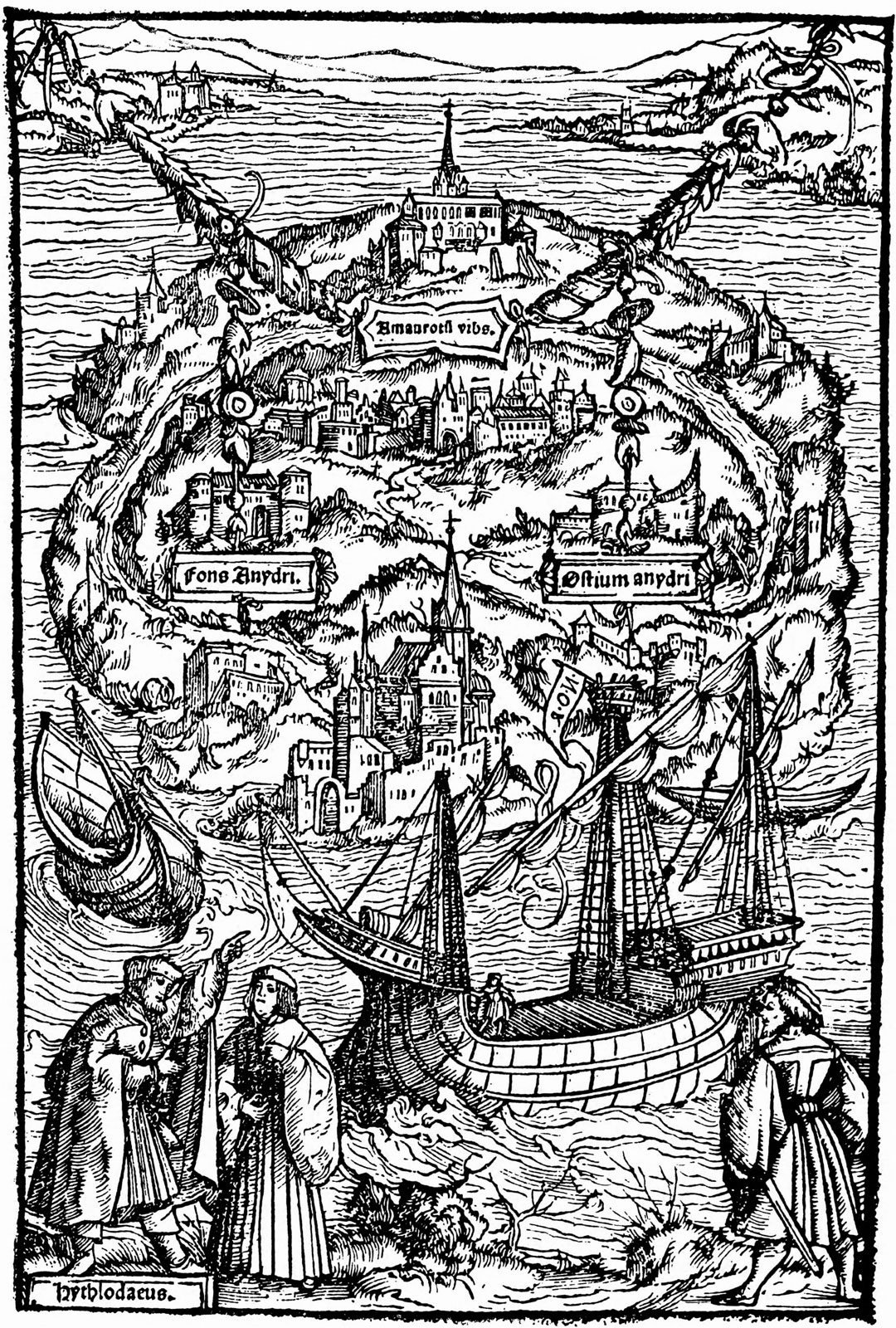

The dream of a society in which private property is abolished and goods are collectively produced and distributed based on need is an old one. It found its first modern expression in Thomas More’s Utopia, in which a European explorer tells of his journey to an island where the inhabitants have successfully maintained such a system. Since More was an opponent of revolutionary upheavals and could see no force in the Western Europe of his day capable of realizing a system like that of his novel, he reached a definite conclusion: “I freely confess that in the Utopian commonwealth there are very many features that in our own societies I would wish rather than expect to see” (More 2016, 113). More’s text was followed a century later by Tommaso Campanella’s City of the Sun with a similar premise. These communist utopias circulated widely among educated readers in Europe, but were generally read by them for either amusement (More’s text in particular satirized aspects of European society) or as part of intellectual exercises in what constituted an ideal society.

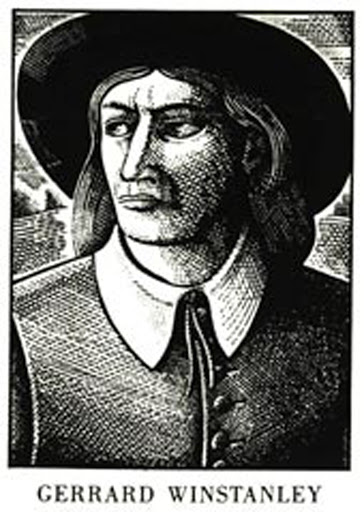

While the 17th and 18th centuries saw efforts to transform the communist utopia into a practical endeavor in one’s own country (notably Gerrard Winstanley’s The Law of Freedom proposing the reorganization of English society circa 1652, and the Conspiracy of the Equals in France), it was not until the first decades of the 19th century, amid the development of large-scale industry, that a new generation of utopian thinkers arose believing they had discovered the means for doing away with exploitation and poverty. Among these were the three preeminent figures of what Marxists term utopian socialism: Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, and Henri Saint-Simon.

While utopian thinkers criticized the blatant oppression, hypocrisy, and seeming irrationality of industrial capitalism, they did not understand the inner workings of the capitalist system and its place in the history of human society. Instead, after describing the aforementioned ills, they sought to invent their own ostensibly superior system. Engels gave a summary of the utopian mindset in his text Socialism: Utopian and Scientific:

If pure reason and justice have not, hitherto, ruled the world, this has been the case only because men have not rightly understood them. What was wanted was the individual man of genius, who has now arisen and who understands the truth. That he has now arisen, that the truth has now been clearly understood, is not an inevitable event, following of necessity in the chain of historical development, but a mere happy accident. He might just as well have been born 500 years earlier, and might then have spared humanity 500 years of error, strife, and suffering. (Marx and Engels 1986, 396)

The utopians likewise held a paternalistic approach toward the workers. Marx and Engels wrote how “the proletariat, as yet in its infancy, offers to [utopian socialists] the spectacle of a class without any historical initiative or any independent political movement. . . . Only from the point of view of being the most suffering class does the proletariat exist for them” (Marx and Engels 1986, 60). Accordingly, when the working-class began to organize itself more firmly from the 1830s onward (such as the Chartist movement in Britain), utopian doctrines began to play a more obviously disruptive role, usually imploring workers to redirect their activities toward setting up solitary settlements whose members would build up the “new society” in isolation from the advanced productive forces created by capitalist development.

Marx and Engels considered the utopians’ criticisms of capitalist society on moral or “rational” grounds to be insufficient. In their view, capitalism arose as a historical necessity. As the productive forces of society grow, a hitherto dominant mode of production becomes antiquated and is replaced with one compatible with the existing economic base of society. Thus slavery gave way to feudalism, and feudalism gave way to capitalism. It is precisely this conception of capitalism as the result of previous economic development that allowed Marx and Engels to consider communism as the result of economic development made possible by capitalism. That is why Marx wrote:

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the now existing premise. (Marx 1976, 57, italics in original)

This premise is capitalist production, and the real movement is led by the proletariat which wages a class struggle to put an end to the supremacy of the bourgeoisie and do away with capitalism, similar to how the bourgeoisie arose within feudal society and struggled for its own supremacy against the nobility.

That is why, to quote an author unsympathetic to Marxism,

Marx never wrote a utopia, and in fact could not have written one, for to have done so would have violated the essence of his method. In all the vast output of his writing, he mentions the communist society only rarely, and then in passing. . . . The utopian describes what would happen if man. . . structured his environment to bring out his best qualities. Marx, on the other hand, was certain of man’s eventual rationality because historical rationality would create the preconditions for man’s consciousness. (Gilison 1975, 29-30, italics in original)

In other words, economic development will both absolutely require and make possible the sort of rationality to fulfill human needs that the utopians criticized as absent in capitalism.

Historically, the terms “socialist” and “communist” have been interchangeably applied to certain utopian thinkers. For instance, Robert Owen’s Book of the New Moral World was described by Engels as containing “the most clear-cut communism possible” (Engels 1977, 320) yet Engels usually used the term “socialist” rather than “communist” to describe Owen. This article will simply use “utopian” or “utopian communism” for convenience (this interchangeable terminology even extends to Jim Jones, who variously described himself as a socialist and a communist, preaching what he termed Apostolic Socialism while speaking of practicing communism in Jonestown.)

The Meaning of Crude Communism

Alongside utopian communism, there has existed a related (though not synonymous) phenomenon which Marx characterized as “crude communism.” It’s defined by the artificial leveling of individuals’ different desires, tastes, and living standards to a proscribed minimum, essentially glorifying poverty as superior to wealth. As with most other utopian strands of communism, ideologists of crude communism ignore or minimize the notion of capitalism as necessary for a definite historical period, instead regrading it as deserving of abolition regardless of the level of productive forces. As a Soviet author noted:

[A] typical feature of the crude egalitarian idea of equality, which has been reproduced at all stages of its development, is a failure to understand that forms of equality are historically determined and connected with the economic base of society. . . The whole system of economic interconnections of communist society is thus regarded as something secondary in relation to the extratemporal principle of ‘perfect equality’ determined by nature and reason. (Pozina 1975, 29-30)

Historically, crude communist doctrines arose in conditions of scarcity and impoverishment. Because a communism built on these foundations is necessarily arbitrary, such things as a desire for greater material goods and opportunity for more creative and varied labor (as opposed to an enforced asceticism and being confined to physically and mentally monotonous work) are looked upon with the utmost suspicion as threats to the ideal which holds the community together. For this reason crude communists also tended to distrust industry and technology, limiting them to a relatively minor role. Since the only way to raise living standards and quality of life in these conditions is to reintroduce capitalistic elements, the inevitable result is a community trained to fear its own members in addition to fearing the hostile outside world. In the words of Engels,

Only at a certain level of development of the productive forces of society, an even very high level for our modern conditions, does it become possible to raise production to such an extent that the abolition of class distinctions can be a real progress, can be lasting without bringing about stagnation or even decline in the mode of social production. (quoted in Pozina 1975, 33)

Marx wrote that the proponents of crude communism remain very much mentally captive to private property:

General envy constituting itself as a power is the disguise in which greed reestablishes itself and satisfies itself, only in another way. The thought of every piece of private property as such is at least turned against wealthier private property in the form of envy and the urge to reduce things to. . . the unnatural simplicity of the poor and crude man who has few needs and who has not only failed to go beyond private property, but has not yet even reached it. (Marx 1977, 95, italics in original)

In other words, by dragging the private property of the rich down to the private property of the poor, the crude communist merely punishes the rich for their wealth without creating the conditions for actually overcoming (as opposed to suppressing for what proves to be a temporary period) private ownership of the means of production.

For Marxists, “[t]he real content of the proletarian demand for equality is the demand for the abolition of classes. Any demand for equality which goes beyond that, of necessity passes into absurdity” (Engels 1977, 132, italics in original). Crude communism “has not yet grasped the positive essence of private property, and just as little the human nature of need, [so] that it remains captive to it and infected by it” (Marx 1977, 96, italics in original). It is this attempt to suppress efforts by individuals to satisfy their needs which more than anything else dooms communities founded on crude communism. Hence Marx’s statement that the development of productive forces “is an absolutely necessary practical premise [of communism], because without it privation, want is merely made general, and with want the struggle for necessities would begin again, and all the old filthy business would necessarily be restored” (Marx 1976, 54).

As with the terms “utopian socialism” and “utopian communism,” there have existed terms that describe the same or similar phenomena as crude communism: egalitarian communism, ascetic communism, barracks communism, etc. To avoid confusion, the term “crude communism” will be used in this article.

Jim Jones and Political Activity

A historian of Peoples Temple and Jonestown has commented:

[Jones] exhibited little class consciousness. . . Not surprisingly, the church never endorsed any labor movements. Few members seemed to involve themselves in unions where they worked. . . Instead, he worked with liberal politicians. Earlier, he worked for conservatives. (Moore 1985, 168-168)

In this regard, Jim Jones was already displaying a characteristic feature of the utopian mindset many years before Jonestown. Marx and Engels wrote that the utopians

habitually appeal to society at large, without distinction of class; nay, by preference, to the ruling class. For how can people, when once they understand their system, fail to see in it the best possible plan of the best possible state of society? Hence, they reject all political, and especially all revolutionary, action; they wish to attain their ends by peaceful means, and endeavour, by small experiments, necessarily doomed to failure, and by the force of example, to pave the way for the new social Gospel.

A natural consequence of this is that “they are compelled to appeal to the feelings and purses of the bourgeois” (Marx and Engels 1986, 60-61).

Because he eschewed independent working-class action, Jones was dependent on the beneficence of the capitalist state in the form of welfare, housing, and other services that Jones could promise members of Peoples Temple, which in turn was linked to supporting Democratic and Republican politicians at different times in different contexts. There was, of course, another motivation, in that Jones made use of politicians to shield himself and the Temple (and Jonestown) from scrutiny, but that isn’t the subject of this article.

A logical conclusion was reached in Guyana, where Jones appealed to the ruling Peoples National Congress party for permission to establish Jonestown. Throughout the rest of Jonestown’s history, retaining the good graces of the corrupt and autocratic PNC remained a vital task for Jones, even though as an ostensible Marxist he should have been identified with the PNC’s rival, the Peoples Progressive Party.

Already in the 17th century, Gerrard Winstanley sought to implement his communist utopia in England by appealing to Oliver Cromwell, bluntly writing to him, “you have power in your hand. . . I have no power” (Hill 1983, 285). Charles Fourier and Henri Saint-Simon similarly tried gaining the support of Napoleon, while Robert Owen appealed no more successfully to the ruling classes of Britain and the United States to finance and sponsor communal settlements to demonstrate the superiority of his new system in miniature form. Such is the fate of those who view the workers as merely the “most suffering” part of society, not as a class with an ability to organize and struggle for its own interests.

In addition, because utopian thinkers often see themselves as great men who have unlocked the solution to society’s ills and need only find adequate support to implement their ideas, independent participation by workers in political life can be interpreted as a hostile act. Hence why the utopian socialists of the early 19th century “oppose all political action on the part of the working class; such action, according to them, can only result from blind unbelief in the new Gospel” (Marx and Engels 1986, 61). In the case of Jones, such activity would have not only called into question his paternalistic attitude toward his followers, but threatened to upset his craving for adulation and control over them.

It is instructive that More’s Utopia, in explaining how the essentially communist system of its inhabitants came about, describes it as the act of a far-sighted and powerful foreign ruler named Utopus who conquered the land, renamed it after himself, transformed its geography (turning it into an island so as to better secure it from outsiders), and “brought its rude, uncouth inhabitants to such a high level of culture and humanity that they now surpass almost every other people” (More 2016, 44). This is the opposite of Marxism, which views communism as not only the outcome of the development of productive forces throughout history, but as the result of a class struggle by workers to replace capitalism when it becomes an obsolete mode of production. It is not difficult to see Jones’ outlook as much closer to the fictional Utopus (and utopian thinkers in subsequent centuries with their paternalistic attitude toward the workers) than to Marx, Engels, or Lenin.

Communal Life in Jonestown

Residents in Jonestown were taught to regard the settlement as operating on communist lines, and a visitor to Jonestown during its last year observed, “There is no possible way for this project to succeed apart from high morale. No one is paid anything. Everyone eats the same food and sleeps in comparable quarters. Everyone is expected to work” (quoted in Moore 1985, 193).

Marx argued that the suitability of communal living arrangements was dependent, like so much else, on the productive forces of society making such a life both logical and appealing.

Without these conditions a communal economy would not in itself form a new productive force; it would lack material basis and rest on a purely theoretical foundation, in other words, it would be a mere freak and would amount to nothing more than a monastic economy. (Marx 1976, 84)

This, of course, was not a perspective the “Marxist” Jones shared.

Everything done in Jonestown was done communally. There were no private places, except perhaps the fields and jungle. The houses weren’t houses at all. They were simply places to sleep. There was no formal dining area. There were few places to lounge. Speakers mounted on wooden posts were aimed at the houses. What privacy that could be found inside or on the benches outside each door, could easily be broken. (Moore 1985, 75)

While not every resident opposed such arrangements, they were bound to create dissatisfaction and tensions within the community which, when combined with the limited resources of the settlement and its numerous other problems (many, to be sure, caused by by Jones’ own self-interested decisions), could only be resolved by coercive methods.

This enforced egalitarianism also magnified the modest differences in living standards, creating the basis for resentment and envy due to privileges that seemed so simple yet so far out of reach of ordinary members. Thus, a journalist commented that Jones’ residence was “larger than most of the other huts we had seen, but not disproportionately so” (Naipaul 1981, 139). Yet it contained such amenities as wire netting, a sofa, and a refrigerator stocked with food and soft drinks. These would be quite mundane in any industrialized capitalist country, yet in the austere conditions of Jonestown, such a discovery might have caused a scandal.

In the words of one historian,

The complaints, the griping and the criticism characterize most utopias. At Icaria, Kaweah, Llano and Altruria, dissent marred regular business meetings. The minute books and newspapers of these groups “related interminable sessions airing personal disputes, questioning minor administrative decisions, or seeking individual dispensations.” One of the many self-criticism letters found in Jonestown reveals exactly these kinds of problems. . . . Life was lived communally — in the fields, in the school, in the pavilion. ‘The members were not socially developed sufficiently to maintain such close relations,’ an anonymous diarist wrote of a Fourierist “Phalanx” in 1870. It could have been written of Jonestown. (Moore 1985, 199)

Marx stated that, “Social activity and social enjoyment exist by no means only in the form of some directly communal activity and directly communal enjoyment” (Marx 1977, 99, italics in original). It is a hallmark of crude communism to draw a sharp division between individuals and society and to attempt to subsume the individual into the collective by downplaying the specific needs of the former. While utopian experiments such as Jonestown usually don’t consciously set out to severely limit individual expression, antagonism is bound to appear as the needs of the individual often cannot be fully met within the limited means of the settlement.

For Marxists, a communist society based on highly advanced productive forces and operating on a global scale will provide full scope for the fulfillment of individual as well as group interests. Hence the statement in the Communist Manifesto that communist society will be one “in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” (Marx and Engels 1986, 53).

The Economy of Jonestown

Like other utopian efforts at establishing isolated communist communities, Jonestown disregarded the above-mentioned material prerequisites for communism and was therefore at the mercy of the outside capitalist world for most food and other essentials. Thus:

Jones’s avowed goal was complete economic self-sufficiency within a year, and to that end virtually everyone who was physically able put in a workday that began at sunrise and ended at sundown. . . . Living space was chronically overcrowded, primarily because of the difficulty and expense [incurred by Peoples Temple members back in the United States] of importing building materials. Although surrounded by a virtually limitless supply of timber, without a mill to turn the timber into lumber, Jonestown was forced to import virtually all of its building materials, in effect carrying coals to Newcastle. (Feinsod 1981, 113)

Most of the settlement’s revenue came from the Social Security its elderly members collected as American citizens, while additional revenue came from certain members engaging in little more than begging in the Guyanese capital of Georgetown.

Because of these and other difficulties, “the group planned to switch to light industrial manufacturing. Artwork, toys and jewelry made by commune members were sold in Georgetown. The tools for the conversion to shoe-making, furniture-making, and brick-making were sitting on the docks on November 18 [Jonestown’s last day]” (Moore 1985, 167). One member of the settlement even suggested a bulk storage operation “that could put us on the map and bring us large contracts with high margins of profit” (quoted in Moore 1985, 204). Had Jones not ended Jonestown’s existence, in all likelihood it would have eventually shared the same fate as all sizable utopian communities which didn’t disband: a gradual shedding of communal aspects and the creation of businesses on a pattern that can be found in any capitalist town.

To quote a Soviet author:

Showing that at a definite historical stage private capitalist property opened up wide possibilities for the development of the productive forces and created objective conditions for socialist transformation, Marx criticized crude egalitarian communism for its inability to grasp the positive essence of private property. . . He showed that the actual abolition of private property and of the relations connected with it presupposed the assimilation, on a new basis, of all the achievements of previous development. (Pozina 1975, 45-46)

A community that can be scandalized if someone was found to possess a personal refrigerator is not in a position to overcome private property.

The idea that one can set up an “advanced,” “pure,” or whatever sort of communist society out of sheer willpower is nonsensical, and would alone be enough to criticize Jonestown as a utopian rather than Marxist endeavor. Engels wrote that “the method of distribution essentially depends on how much there is to distribute, and that this must surely change with the progress of production and social organization” (quoted in Pozina 1975, 66, italics in original). Hence why Marx differentiated between two phases of communist society. The first or lower phase (often referred to by Marxists as socialism) is built not “on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emergesfrom capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally and intellectually, still stamped with the birth marks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society—after the deductions have been made—exactly what he gives to it. What he has given to it is his individual quantum of labour.” Only in the second phase, made possible in part through even more advanced productive forces than exist during the first phase, can “society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” (Marx and Engels 1986, 319-321, italics in original).

Thus in regard to socialism (i.e., the lower phase of communism):

Certain inequality as regards the material position, sanctioned by and born of distribution according to work, does not blind Marxists to the irreplaceable role of the principle of material stimulation in raising social production, and, consequently, in creating the material prerequisites necessary for the transition to distribution according to needs. (Pozina 1975, 67-68)

Security in Jonestown

Utopian communist settlements depend on constant commitment to an ideal. TThis made it exceedingly easy to cast blame on individuals’ lack of “advanced” consciousness rather than confront more fundamental economic and/or administrative problems. This is not just a case of finding scapegoats, but reflects the fact that one, two, or a handful of individuals really can inflict great damage on a settlement through “uncooperative” behavior and the potential demoralizing impact of their departure.

While Jones clearly had his own peculiar reasons to introduce draconian security measures and discipline in Jonestown, the near-spartan atmosphere and constant reiteration of the need to uphold ostensibly communistic principles in daily life meant the settlement was constantly menaced by dissatisfaction and, occasionally, plots to escape. This was exacerbated by regular exhortations to self-sacrifice amid what seemed to be constantly deteriorating prospects.

Rather than detail the numerous forms of petty regulation and punishment (a Relationship Committee to control questions of love and sex, a Special Care Unit to drug real and imagined dangers to the community, etc.), it is only necessary to note the consequences of such measures. For instance, Mike Prokes (one of those responsible for administering the settlement) cited the personal problems of many of its inhabitants as justifying the need for a “tight structure.” A journalist likened Prokes and other administrators to self-appointed “doctors” considering themselves tasked with “curing” an army of patients:

[These] were not simply poor and oppressed and in need of love. They were also emotionally disturbed, maladjusted. . . It was an autocratic conception, and it must have given rise to frightening temptations and actions. Prokes unconsciously strays from the language of socialism and brotherhood to the language of psychiatry. (Naipaul 1981, 150-151)

Another author notes, “Field workers had their breaks at unscheduled times. No one knew when a day off was coming. This was to prevent conspiracies and flight” (Moore 1985, 308). Settlement member Odell Rhodes recalled that the fear of punishment for being accused of loafing at work, combined with an increasing preoccupation over external and internal enemies, undermined productivity as “everybody was starting to worry about everything except what we were there to do—to make Jonestown a good place to live” (quoted in Feinsod 1981, 133).

Aside from Jones’ own selfish motives in imposing such measures, much of this goes back to the concern of a number of utopian thinkers of the danger of private property being restored without constant vigilance. Already in More’s Utopia, it was “a capital offence to make plans about public business outside” the organs of government, so as to prevent officials “from conspiring together to alter the government and enslave the people” (More 2016, 50). Gerrard Winstanley wrote of his own sought-after communist utopia:

He or she who calls the earth his and not his brother’s shall be set upon a stool, with those words written in his forehead, before all the congregation; and afterwards be made a servant for twelve months under the task-master. If he quarrel, or seek by secret persuasion, or open rising in arms, to set up such a kingly [i.e. private] property, he shall be put to death. . . No man shall either give hire or take hire for his work; for this brings in kingly bondage. If any freemen want help, there are young people, or such as are common servants, to do it, by the overseer’s appointment. He that gives and he that takes hire for work, shall both lose their freedom, and become servants for twelve months under the task-master. (quoted in Hill, 383)

Winstanley’s fear of one man deciding to labor for another was not without foundation. Capitalism in the conditions of 17th-century England was a clear historical advance as compared to both feudalism and the agrarian-based communist system he proposed. Like other utopias, including Jonestown, such punishments were designed to prevent a more efficient mode of production from asserting itself. August Bebel, a leading Marxist in his day, had no such fear. He knew that the new society would be built not on the foundations of impoverishment, but on the basis of the utmost development of productive forces. That is why he wrote that

Winstanley’s fear of one man deciding to labor for another was not without foundation. Capitalism in the conditions of 17th-century England was a clear historical advance as compared to both feudalism and the agrarian-based communist system he proposed. Like other utopias, including Jonestown, such punishments were designed to prevent a more efficient mode of production from asserting itself. August Bebel, a leading Marxist in his day, had no such fear. He knew that the new society would be built not on the foundations of impoverishment, but on the basis of the utmost development of productive forces. That is why he wrote that

should [someone] wish to work for somebody else to enable that person to indulge in dolce far niente [i.e. idleness], or should he wish to share his title to the social products with him, there is nobody to prevent him from doing so. But no one can compel him to work for another’s advantage, no one can withhold from him any part of his title to the social products he has earned. Everyone can satisfy all his fulfillable wishes and claims, but not at the expense of others. (Bebel 1976, 54, italics in original)

In Jonestown and other utopian experiments, the mere thought of working for someone else really could have dangerous consequences, insofar as it would doom the community’s communist pretensions by inducing mass demoralization. In a society that has well and truly overcome capitalism rather than merely trying to suppress it, it would be scarcely more dangerous than fantasizing today about a return of slavery or feudalism. Hence why the Communist Manifesto stated, “Communism deprives no man of the power to appropriate the products of society; all that it does is to deprive him of the power to subjugate the labour of others by means of such appropriations” (Marx and Engels 1986, 49).

Conclusion

All that I have written is sufficient to demonstrate that the communism behind Jonestown was of a utopian nature, not a Marxist one. Regardless of Jones’ revolutionary vocabulary, and whatever admiration he had for the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, the DPRK, and similar countries, I would argue that the history of American communism ought to place him far closer to John Humphrey Noyes than the likes of Eugene Debs or William Z. Foster.

As has been shown, the belief that one can escape capitalism and build an ideal community many miles away is not a new one. Utopian sentiments are an understandable response to exploitation and poverty, and there were those in Jonestown who felt, in a sense, liberated despite all the inherent problems of such settlements and despite Jones’ own self-destructive policies. Hence Odell Rhodes, recalling his first months in the settlement:

I could have been listening to the band rehearse or watching TV, but lots of times I just wanted to have a look at what we’d accomplished that day. There was so much satisfaction in it; I mean there I was, thirty-three, thirty-four years old or whatever, never done a damn thing worth shit in my life, and all of a sudden I’m watching myself make 10,000 banana trees into 70,000, watching us push the jungle back a few feet more every day. . . it was just entirely different than working for money. I’d be tired as hell, but I felt like I couldn’t wait for it to be morning again so I could get back at it again. (quoted in Feinsod 1981, 115-116)

Likewise, “The love that had made the community was tangible. Hand-lettered signs, artwork, a playground, neatly-built houses, each one painted, each one surrounded by flowers and plants” (Moore 1985, 76).

But while this may be a liberating experience for numerous individuals, it cannot be a method of liberating the world or even a lasting method of keeping the individuals themselves liberated before the community is obliged to surrender to the vaster productive powers of capitalism. Hence why an official of the Cuban embassy in Guyana gave the following advice to emissaries from Jonestown (one of whom summarized it as follows): “This is not exactly the way the society should be changed. We [i.e. Jonestown] should not just include ourselves. We should try to get involved with the real contradictions that are in society” (quoted in Moore 1985, 166-167). The Soviet embassy, by contrast, was more willing to flatter Jones amid the prospect of a thousand Americans openly identifying with the USSR and seeking to relocate the settlement there.

As Engels stated,

Since the historical appearance of the capitalist mode of production, the appropriation by society of all the means of production has often been dreamed of. . . Like every other social advance, it becomes practicable, not by men understanding that the existence of classes is in contradiction to justice, equality, etc., not by the mere willingness to abolish these classes, but by virtue of certain new economic conditions. The separation of society into an exploiting and an exploited class, a ruling and an oppressed class, was the necessary consequence of the deficient and restricted development of production in former times. So long as the total social labour only yields a produce which but slightly exceeds that barely necessary for the existence of all; so long, therefore, as labour engages all or almost all the time of the great majority of the members of society—so long, of necessity, this society is divided into classes. . . . [This] will be swept away by the complete development of modern productive forces. (Marx and Engels 1986, 424-425)

By peddling utopia, Jones was also promoting despair as so many modern utopians do. He kept his followers away from any real participation in popular struggles (except as bussed-in protesters to fulfill political favors and to impress persons or organizations), and by relocating them to the jungles of Guyana made it that much easier to justify his notion of revolutionary suicide, arguing that the congregation’s opponents – both real and imagined – would never leave them alone, and that these thousand Americans, most of them elderly or very young, could scarcely pose a challenge to capitalism (as indeed by themselves they could not.)

It would not be entirely fair to end this article without acknowledging that the history of the international communist (i.e. Marxist) movement has not been without its own errors in regard to the transformation of society on new lines. The experience of the USSR and similar states during the 20th century showed that they had greatly overestimated the extent of their own productive forces while underestimating the prospects of capitalism. Seeing not just the first (socialist) phase of communist society as easily attainable, but even the second phase (with distribution according to need) as not far off, the general response was to react to economic problems by imploring the population to be better communists. As one Western critic noted:

The [Soviet] press continually discloses these failures to live up to the selfless, altruistic standards by which men would live in a communist society. The effort to make men fit to live in that future communist society is a consuming interest and major activity of the Soviet regime. The ‘upbringing’ of the ‘new socialist man’ is a self-imposed project of the regime and, in a sense, is the justification for the attempt to monopolize the thoughts of Soviet citizens through the manifold activities of the ideological machine, and the exclusion of alien (i.e., contaminating) influences.

Daily behavior naturally falls short of these lofty goals as “Soviet citizens are not. after all, the ‘new communist men’ of the future society” (Gilison 1975, 14-15).

Premature socialization of practically the entire Soviet economy, as in similar states, ultimately led to the growth of such things as black markets and bribery to fill in the gaps and address the needs of individuals which a relatively backward planning system was unable to satisfy. This situation created cynicism among the population and did much to discredit communism. As Marx and Engels put it, “The ‘idea’ always disgraced itself insofar as it differed from the interest” (quoted in Pozina 1975, 68). The establishment of communism will evidently be a much more protracted process, and as part of this process, it remains important to point out utopian forms of thinking whose appearance clearly isn’t limited to solitary communal settlements.

Utopian experiments, however, are not entirely without value. While one can find much that is naïve, obsolete, or simply wrong in 16th-20th century efforts to envision or reorganize society on rational lines, bits and pieces will doubtlessly be of use for the future establishment of a communist society, even if it’s primarily by providing examples of what not to do. In this respect, Gerrard Winstanley was showing the right degree of modesty in declaring of his own proposed communist utopia:

It may be here are some things inserted which you may not like, yet other things you may like, therefore I pray you read it, and be as the industrious bee, suck out the honey and cast away the weeds. Though this platform be like a piece of timber rough hewed, yet the discreet workmen may take it and frame a handsome building out of it. (quoted in Hill, 285)

Works cited

Bebel, August. Society of the Future. Moscow: Progress Publishers. 1976.

Engels, Frederick. Anti-Dühring. Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science. Moscow: Progress Publishers. 1977.

Feinsod, Ethan. Awake in a Nightmare. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1981.

Gilison, Jerome M. The Soviet Image of Utopia. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1975.

Hill, Christopher (ed). Winstanley: The Law of Freedom and Other Writings. London: Cambridge University Press. 1983.

Marx, Karl. The German Ideology. Moscow: Progress Publishers. 1976.

Marx, Karl. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Moscow: Progress Publishers. 1977.

Marx, Karl & Frederick Engels. Selected Works. Moscow: Progress Publishers. 1986.

More, Thomas. Utopia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2016.

Moore, Rebecca. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press. 1985.

Naipaul, Shiva. Journey to Nowhere: A New World Tragedy. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1981.

Pozina, L. Marxism Versus Crude Communism. Moscow: Novosti Press Agency Publishing House. 1975.