There is no doubt that Jim Jones was the central figure in the Jonestown massacre. His flamboyant speeches, irresistible charisma, and his proclamation of himself as a saviour, would develop “audience corruption” when Jones successfully gained a support base convinced of his Messiah status.[1] That success allowed him to draw his audience into his church even more deeply, and eventually to their deaths. But while his cult of personality is most significant, this essay argues that this reductionist view does not consider the societal factors and ideology.

Jones pursued numerous strategies to strengthen his leadership by addressing his followers’ needs, by developing “organisational growth,” and by creating “dependency relations.” Peoples Temple began this through helping members find jobs, and providing free food.[2] However, this empathy that became his most effective means of persuasion[3] would result in Jones to believe in his divinity as a provider.[4] The Letter Killeth,[5] a document criticising the flaws of the Bible demonstrates this.[6] Jones claimed to be a messenger sent by the true God and challenged Jesus’ claim to be the sole Messiah.[7] “Yes, I’ll become Jesus Christ… But I don’t have to be… I’ve done enough in the name of Jim Jones.”[8] Ultimately, he would become “all things to all people” and achieve a divine status from his following.[9] As a result, the relationship between preacher and congregant shifted radically to one between God and disciple.

“Organisational growth” as a form of indoctrination was established early on. Faith healings were a big part of attracting members. First encountering this in the Seventh Day Baptist Church, Jones would effectively utilise faith healings to keep “individual crowds enthralled.”[10] This was publicised heavily through The Living Word, an early publication of the Temple.[11] The magazine was filled with testimonials of those who had suffered both physical and “mental and spiritual stagnation,”[12] but who had been cured by the “Loyal Messenger”[13] Jim Jones. Through this, Peoples Temple gained credibility. As government officials visited services, and membership of the church became “a sizable voting bloc,” the soft power of the Temple dramatically increased.[14] Significantly, then, not only did the Temple grow as a community, Jones gained legitimacy both socially and politically. This credibility was a crucial factor for a smooth transition into a commune in Guyana.

Role of Speeches

Much of Jones’ charisma come through in the power – the cadences, the rhythms – of his long, free-form addresses to his congregation. As Temple scholar Fielding McGehee notes, “What you thought Jim said depended on who you were.”[15] In other words, it was not the content, but rather the unique tone of Jones’ speeches that appealed to his audience. Guinn describes Jones as someone who “preached like a black man and got things done like a white one.”[16] Appealing to the black demographic of San Francisco where the Temple located itself during its height of size and influence persuaded potential members to join simply “to be part of a church that he [Jones] personally led.”[17] And even as the carnage unfolded around him on Jonestown’s final day, Jones asked rhetorically, “Are we black… or what are we?”[18] Jones was white, but his use of the word “we” was met with applause and praise: he appealed to the pathos of his followers while connecting the church through racial unity. Thus through the development of a credible organisation with a charismatic leader, a cult of personality had emerged with a loyal and devoted membership. This loyalty would find its ultimate expression on November 18, 1978.

Maintenance of Cult of Personality

Maaga argues the significance of charismatic leadership lies more in a group’s development rather than when it is “consolidating its life as a community.” Thus, “Jones’ leadership was more central in California than in Jonestown.”[19] This is true only to a limited extent, though, as without Jones’ maintenance of his cult of personality in Jonestown, a tragedy of this scale would not have been possible. Johnson’s description of Jones’ final strategy of strengthening leadership would be to “cut previous social ties” and “seek an isolated environment”: This environment would act as a utopian community for the residents.[20] When Jones arrived in Jonestown to stay in 1977, the presence of a cult of personality became more dominant than ever.

Poetry from Jonestown resident Barbara Walker reflected her loyalty both to the commune and to Jones wen she wrote, “This is our home in which we’re ready to defend.”[21] This was in response to the Six Day Siege during the fall of 1977, when community members believed they were under attack from Guyanese military forces. Although this was a smaller scale event, the will to fight for Jonestown was evident prior to the massacre. Greenberg describes Jones’ methodology of political control in Jonestown as “cognitive and emotional control of the mind.”[22] Dube echoes Greenberg’s argument claiming, Jones displayed “dogmatic teaching, bold confidence, and arrogant assertiveness.”[23] This provided Jones more dominance and power over the commune, and a higher degree of respect from the members as he asserted his influence and importance, which ultimately proved to be irresistible to a broad range of individuals. However, as Weightman asserts, Jones’ charisma would have been worthless without recognition from the supporters. A credible ideology was required to gain the trust of the members; Jones complemented his charisma with comprehensive ideology.[24] His inner circle of leaders assisted him by reviewing all information coming in and out of Jonestown. Jones was the sole charismatic figure of authority in the isolated commune.[25]

Role of Cult of Personality at the Massacre

Though the challenges to Jones’ cult of personality became most apparent with the arrival of Congressman Leo Ryan, they were not significant on the day of the massacre. Jonestown had filed petitions of protest of the visit, its lawyers had requested that he do not come, and – when those tactics failed – Jim Jones led a community meeting, coaching members how to respond to questions from the visiting delegation. When that proved for naught as well, Jones took the final step, to persuade his members that revolutionary suicide was the only course of action left. His cult of personality is largely accountable for this successful persuasion.[26]

The Death Tape recording the final moments of Jonestown, shows to a large extent, Jones had successfully indoctrinated his commune members. As Jones spoke for the final time, member Christine Miller resisted: “As long as there’s life, there’s hope.”[27] This was the last record of resistance – however hopeless – to Jones’ careful plan. Reinforcing his role as a Messiah, Jones himself stated, “Without me, life has no meaning.”[28] Members shouted down Miller’s resistance with calls of, “You’re only standing here because he [Jones] was here.”[29] More common were the final testimonies reflecting on Jones’ significance, as Jonestown residents referred to Jones as “Dad”[30]and as “the only god.”[31] While revolutionary suicide may have been the ideological act of the massacre, the willingness of the followers to abide by the leader’s demands displayed absolute commitment to Jones, not his ideology. Annie Moore, Jones’ personal nurse, wrote “we died because you [the outside world] would not let us live in peace,”[32] suggesting Ryan’s visit was the sole reason the deaths occurred. However, the recording depicts a commune willing to submit their lives to Jones words whatever occasion he might have chosen.[33] Thus Jim Jones’ cult of personality indeed plays an extraordinary role in the outcome of the Jonestown massacre.

The Role of Ideology

Nonetheless, a widely accepted ideology was required to act as the foundations for a flourishing cult of personality, and this ideology was a more prominent factor. Though little of Peoples Temple’s ideology was original, McGehee suggests it was the unique combination of principles and religious doctrines that elevated ideology to be the most significant cause of the Jonestown massacre.

Influence of Father Divine

Jones’ relationship with Father Divine was the beginning of the Temple’s articulation of an ideology. Weightman argues Jones’ intended to “study the master” in attempts to “appropriate his [Divine’s] techniques.”[34] Even Jones’ cult of personality was to an extent inspired by what he had witnessed from Father Divine’s church, where Jones felt Divine “was a leader who was appreciated.”[35] Eventually, Jones would compare himself to Divine in his own church, mirroring “the control he [Divine] held over every aspect of his followers’ lives.”[36] Clearly, Jones’ cult of personality was limited: He needed to borrow ideology from others to grow and develop his own message.

Apostolic socialism and broader socialism

Jones’ only original articulation of an ideology, though its biblical originality may be contested, was “apostolic socialism,” which Moore describes as “the truest form of love, where barriers between people fall because total equality exists.”[37] This doctrine would justify the radical sharings of Jones as it would appeal to anyone “regardless of race or social position.”[38] Preaching apostolic socialism was critical in the growing devotion to the church as members “sincerely believed in its practice.”[39] There is no doubt this ideology helped Peoples Temple stand out as a new religious movement. The broader ideology, communism and socialism, was one Jones aligned himself with, and preached throughout Jonestown’s history, including the final day. Remarkably “socialism eventually eclipsed Christian doctrine in Jones’ teachings.”[40] Peoples Temple was simultaneously a revolutionary movement that strengthened the unity of the church. Jones, who quoted Mao as often as he quoted Lenin, would use ideology to justify his radical decisions. Combined with a charismatic cult of personality, such ideology was not questioned.[41]

Amid general anti-communist sentiments, Jones heavily criticised American capitalism calling for a “socialist revolution.”[42] This resonated strongly among impoverished Temple members.[43] Jones would equate biblical messages to socialism as a form of “changing hearts through example, not coercion.[44] This form of socialist ideology was crucial in convincing an American-based church to migrate to the isolated Guyanese environment. He would exaggeratedly justify migration as an escape from the “hostility and hopelessness” of America, and advocated socialist principles as the cause for struggles and sacrifice.[45] The final sacrifice was the mass suicide in the name of socialism, as Jones called upon his “socialistic Communists” to “die with some dignity.”[46]Revolutionary suicide was, in part, the ultimate test of loyalty to the socialist struggle.

Communalism and Revolutionary Suicide

For such radical ideology to be preached, Jones needed an isolated environment. With a tight-knit community under his control, Jones could preach his doctrine – including the concept of revolutionary suicide – without fear of alternative voices arguing a successful dissent. As the ideology of a “Promised Land”[47] was an important aspect for Jones’ church, the move to Guyana was met with “enthusiasm,” as survivor Phil Blakey recalls.[48] Johnson suggests the “migration to an isolated environment” was not advantageous to the growth of Jones’ influence and power,[49] but letters and diaries reflect a greater admiration towards Jones in Guyana. The satisfaction of members in the isolated commune made them vulnerable to acceptance of Jones’ radical ideologies.[50]

Jones’ interpretation of revolutionary suicide was both unoriginal and inconsistent. To appeal to his black audience, he shanghaied the concept of revolutionary suicide – the act of dying for the greater good – from Black Panther Party leader Huey Newton.[51] This shows the limitations to Jones’ cult of personality, as his persona was incomplete without borrowed inspiration. Jones further recalled biblical instances of revolutionary suicide, including Masada, the community of Jews who “committed suicide rather than surrender to a Roman army.”[52]This rhetoric was prevalent in Temple meetings and Planning Commissions; this comes to show Jonestown’s version of a Masada was meticulous and calculated.[53] Revolutionary suicide was rehearsed several times before November 18 in “White Nights,” during which sirens would echo throughout the entire commune and “rifle-toting” members would roust individuals from their cabins.[54] Revolutionary suicide was the ideological justification for the massacre.

Combining Ideologies

Jim Jones had competing, sometimes contradicting, ideologies that he preached, but he was able to reconcile them into acceptable messages. Most importantly, he believed “individual suicide was wasteful” but “mass suicide… was admirable.”[55] Communalism was important for unity, and revolutionary suicide would be the only appropriate act to allow display it. Secondly, revolutionary suicide seemed to “redeem a fully human identity from a dehumanized life and death in America.”[56] Socialist values would characterise how Jones referred to the massacre: “The End of a Dream.”[57] The build-up of strongly resonating ideologies throughout the history of Peoples Temple, from its roots in Indianapolis to Jonestown enabled the tragedy to occur.

Social Division

However, it is also important to examine the social division that created a support base subject to indoctrination through ideology and charisma. Certainly it was possible that Jones, one of the few white ministers in the Midwest promoting racial equality in the 50s and 60s, could become a role model for civil rights. His unique appeal of equality was integral for gaining a loyal and supportive audience for the movement to flourish. It was his ability to take advantage of a vulnerable population – disenfranchised, low income, under-educated, subject to discrimination – that provided him the necessary catalyst in emerging as a religious movement.

A church for the oppressed

American segregation was rampant in the 1950s. “African Americans were desperate to escape Dixie,” and many thought that they found refuge in the nearby state of Indiana,[58] but Indiana’s trade unions “voted not to accept blacks as members,” causing greater socioeconomic divide and poverty.[59] Under harsh conditions, the church was “their only source of solace.”[60] Peoples Temple became a Mecca for this rejected black population. Moore argues the Temple was a “black movement,”[61] and Rose adds that Jones took advantage of the “lack of religious authority in America” to transform his church into a movement.[62] Early Temple magazines, such as The Open Door and The Living Word attracted members through statements that “the door is open so wide that all races”[63]were welcome and would be out of “bondage.” Peoples Temple was capable of emerging into a popular religious movement for black Americans – and it did that for the circles it created for itself – but the challenge was to maintain that support. Jones would have to prove this throughout the Temple’s history.

One method for recruitment into the Temple was to target the oppressed and “welcomed” egalitarianist sentiments,[64] and the church appealed to vulnerable populations through several methods. The church offered soup kitchens and community clothing banks, and showed a large concern for social issues. Jones’ kindness was genuine rather than manipulative,[65] as was his promotion of “racial healing” through supporting the black community.[66] However, what elevated the loyalty and support beyond attracting black supporters was Jones’ adoption of “black worship traditions,” and he spoke “symbolic and religious language” that resonated with his audience.[67] Examples of this include frequent, spontaneous shouts of praise and exaltation during sermons that are more frequent in black worship services.[68] Harrison claims that if Jones did not “appreciate” such traditions, the following of the Temple would have been much smaller.[69] According to Smith, Jones’ ability to take the “irrelevant” black tradition in society and make it “relevant” in several contexts was crucial in gaining support. Sermons were tailored to discuss “justice and communal empowerment.”[70] Lincoln and Mamiya disagree. Though they acknowledge Jones tried to “mould himself” into the black worship traditions, he was unsuccessful.[71] This is justified by complex ideology rejected by the conservative black audience. The validity of the latter perspective undermines the significance of social division as a way of gaining support.

Black Preaching Movement

Peoples Temple to a large extent became an embodiment of a “black” church. When examining the emergence of the church, it is clear that alienation from society enhanced the vulnerability of members that could eventually be manipulated. By 1962, Indianpolis had become relatively racially integrated, and Guinn claims Jones was “entirely responsible.”[72] This is true to an extent – especially in the Temple itself – as the attitude of white members also experienced shifts towards racial equality. A white teenager, Rick Cordell claimed, “You were accepted just as you were… not judged by the way you looked.”[73] Jones also demonstrated his commitment to racial equality by adopting Korean, black, and Native American children. He called them his “rainbow family,” which was accepted by church members even if rejected by society at large. Revisionist contradictions to the mainstream beliefs grew the identity of the church.[74]

Long term consequences of social division

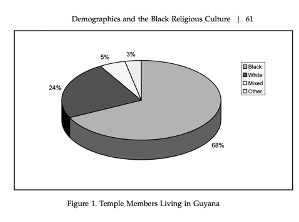

Societal disapproval followed the Temple to California, where it experienced attacks and harassment. The incident in which the San Francisco Temple was fire-bombed became the trigger event for the establishment of a commune in Guyana.[75] Jones would exploit the racist and xenophobic tendencies of American society, partnered with his own socialist principles, as his justification for establishing a new commune. Blacks may not have had the same percentage of residents in Jonestown as they did in San Francisco, but as the accompanying chart shows, on the main the Guyana contingent reflected its racial and ideological roots.[76]

Whether it had been his preaching of socialist ideology, or his expanding a cult of personality, Jones appealed to a black audience. Creating Jones’ “utopian” world that would contradict any form of discrimination in America was crucial for keeping members satisfied. His appeal to black followers was not only crucial in the beginning, its results manifested in the final moments of Jonestown.

However, social division, though a contributing factor in the massacre itself, was not the most significant factor. In the Death Tape, an unidentified woman says “the biggest majority of the people that left here [Jonestown] were white… it broke my heart.” She ends her remarks by saying “So we might as well end it now.”[77] This suggests with white members leaving the commune, black members would still be isolated, as they had been in their collective pasts, and death would be a considerable choice over integrating in exclusionary America.

Conclusion

To understand the complexity of the Jonestown massacre requires a thorough analysis of the several intertwined factors. In all significant moments of Peoples Temple history, whether it be in emerging into a credible church, the move to Jonestown, or the horrendous final day, an ongoing cult of personality filled with radical ideology taking control of a vulnerable population was prevalent. Jim Jones’ unique methods of adopting black worship tradition as a white man would demonstrate his manipulation of a divided society to build a religious movement, and hint of his initial generosity. To maintain and consolidate influence and power, a cult of personality, both challenging orthodox Christianity while adopting a Messiah complex, was pivotal in transforming a pure Christian movement to a radicalised one. This cult of personality would exponentially grow in magnitude and support as the church’s history progressed.

However, ideology, both unique in combination and radical in socialist principles, was the most significant short term cause, and extremely significant long term cause of the Jonestown massacre. The cult of personality may have been a significant cause to a large extent, but it required a certain ideology to be embedded in Jones himself to maintain support, and thus cannot be seen as the “most significant cause.”

Bibliography

Barker, Eileen. “Religous Movements: Cult and Anticult Since Jonestown.” Annual Review of Sociology 12 (1986): 329–46.

Black, Taylor, “American Horror Story: On the Cult of Personality”, Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple (hereafter, Alternative Considerations). September 30th, 2018 (accessed June 20th 2023)

Blakey, Phil. “Snapshots from a Jonestown Life.” Alternative Considerations, September 25th, 2018. (accessed June 20, 2023)

The Board of Directors of Peoples Temple, “Jonestown Petition to Block Rep. Ryan” November 9, 1978. Alternative Considerations. (accessed June 21, 2023)

Burke, John R. “AMBASSADOR JOHN R. BURKE”. Interview by Charles Stuart Kennedy. The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Marshall Plan Series, May 26, 1989.

Carter, Tim. “The Big Grey.” Alternative Considerations ,2003.

Chidester, David. “Rituals of Exclusion and the Jonestown Dead.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 56, no. 4 (Winter 1988): 681-702.

–––––. Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2003.

Conroy, J Oliver. “An apocalyptic cult, 900 dead: remembering the Jonestown massacre, 40 years on.” The Guardian, November 17 2018. (accessed June 20, 2023)

Dube, Bekithemba, Milton Molebatsi Nkoane and Dipane Hlalele, “The Ambivalence of Freedom of Religion, and Unearthing the Unlearnt lessons of Religious Freedom from the Jonestown Incident: A Decoloniality Approach,” Journal for the Study of Religion, ASRSA, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2017): 330-349.

“A Feeling of Freedom.” photo, 1978. Alternative Considerations (accessed 20 Jun 2023).

Feinsod, Ethan. Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown the Only Eyewitness Account. New York: W. W. Norton, 1981.

Green, Ernest, “Jonestown,” a review of five books, Utopian Studies, Penn State University Press, Vol. 4, No. 2 (1993), 162-165.

Greenberg, Joel, “Jim Jones: The Deadly Hypnotist,” Science News, Society for Science & the Public, Vol. 116, no. 22, (Dec. 1, 1979): 378-379+382.

Guinn, Jeff. Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014.

–––––. The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

“Guyana: How It Was.” Produced by Tony Russomanno. Aired November 25, 1978, on KSFO Radio. Alternative Considerations.

Harris, Duchess and Adam John Waterman “To Die for the Peoples Temple: Religion and Revolution after Black Power.” In Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, 103-122. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

Harrison, Milmon F. “Jim Jones and Black Worship Traditions.” In Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, 123-138. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

Johnson, Doyle Paul. “Dilemmas of Charismatic Leadership: The Case of The Peoples Temple.” Sociological Analysis 40(1979): 315-23.

Jones, Jim. “An Apostolic Monthly,” The Living Word Vol #1, edited by Garrett Lambrev, 1-38.

–––––. “God Saves Lives Through Picture,” The Living Word, July. 1972, 1-38

–––––. 1978 “Jonestown Death Tape.” Transcript of speech delivered at Jonestown, Guyana, November 18, 1978. Alternative Considerations. (accessed 20 Jun 2023)

–––––. 1972 “Q1057-5.” Transcript of speech delivered at Los Angeles, California, 1972. Alternative Considerations. (accessed 20 Jun 2023)

–––––. “To All Man Kind,” The Open Door, April. 1956, 1-4

Jones, Stephan, “Restored Humanity,” Alternative Considerations, July 28 2012.

Kennerly, David Hume. Cult of Death. Photograph. ABCnews. November 18, 1978.

Kilduff, Marshall. The Suicide Cult: The Inside Story of the Peoples Temple Sect and the Massacre in Guyana. New York: Bantam Books, 1978.

Klippenstein, Kristian D. “Jones on Jesus: Who Is the Messiah?” International Journal of Cultic Studies 6 (2015): 34-47.

Knerr, Michael E. Suicide in Guyana. New York: Belmont Tower Books, 1978.

Kohl, Laura Johnston. Jonestown Survivor: An Insider’s Look. New York: iUniverse, 2010.

Lincoln, Eric C. and Lawrence H. Mamiya “Daddy Jones and Father Divine: The Cult as Political Religion.” In Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, 28-46. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

Maaga, Mary McCormick. Hearing the Voices of Jonestown. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1998.

McGehee III, Fielding M. “Interview with Fielding M. McGehee III.” By Alex Jung. (June 22, 2023)

Moore, Carolyn Layton. Letter to John and Barbara Moore, October 11, 1977. In “Letters from Carolyn Moore Layton.”Alternative Considerations.

Moore, Rebecca. “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture

of the People’s Temple.” In Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, 57-81. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

–––––. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family

Involvement in Peoples Temple. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1985.

–––––. “What is Apostolic Socialism?” November 9, 2018, Alternative Considerations (accessed June 25, 2023).

“People Temple Full Gospel.” Indianapolis Recorder, Dec. 10, 1955 (accessed 20 Jun 2023).

Richardson, James T. “People’s Temple and Jonestown: A Corrective Comparison and Critique.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 19, no. 3 (1980): 239–55.

Rose, Stephen C. Jesus and Jim Jones. New York: Pilgrim Press, 1979.

Ryan, Leo. Leo Ryan to Jim Jones, November 1, 1978. In Leo Ryan Telegram to Jim Jones (Text), edited by Rikke Wettendorff. Alternative Considerations.

Shupe, Anson, David Bromley and Edward Bresche. “The Peoples Temple, the Apocalypse at Jonestown, and the Anti-Cult Movement” In New Religious Movements, Mass Suicide, and Peoples Temple: Scholarly Perspectives on a Tragedy, edited by Rebecca Moore and Fielding McGehee III, 153-178. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1989.

Smith, Archie Jr. “An Interpretation of Peoples Temple and Jonestown: Implications for the Black Church.” In Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, 47-56. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

Smith, Jonathan Z. Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Sutton, Candace. “918 dead in jungle: ‘How I survived the Jonestown massacre'”, News.com.au, October 29, 2018 (accessed Jun. 21, 2023).

United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. RYMUR 89-4286-HH-6-A-2.., 1975, California.

Walker, Barbara. “The Front Line in Ballad and Thought.”: Poetry, 1977 (accessed 20 Jun 2023).

Weightman, Judith Mary. Making Sense of the Jonestown Suicides: A Sociological History of Peoples Temple. New York: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1983.

–––––. “The Peoples Temple as a Continuation and an Interruption of Religious Marginality in America.” In New Religious Movements, Mass Suicide, and Peoples Temple: Scholarly Perspectives on a Tragedy, edited by Rebecca Moore and Fielding McGehee III, 5-22. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1989.

Wessinger, Catherine. How the Millennium Comes Violently. New York: Seven Bridges Press, 2000.

Notes

[1] Archie Smith Jr., “”An Interpretation of Peoples Temple and Jonestown: Implications for the Black Church,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004), 48.

[2] Doyle Paul Johnson, “Dilemmas of Charismatic Leadership: The Case of The Peoples Temple.” Sociological Analysis 40 (1979): 315-23.

[3] Jeff Guinn, The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 80.

[4] Taylor Black, “American Horror Story: On the Cult of Personality” Jonestown Institute. September 30th, 2018, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=81385 (accessed June 20th 2023).

[6] Kristian D. Klippenstein, “Jones on Jesus: Who Is the Messiah?” International Journal of Cultic Studies 6 (2015): 34-47.

[7] Catherine Wessinger, How the Millennium Comes Violently. (New York: Seven Bridges Press, 2000), 37.

[8] Jim Jones, “Q1057-5,” transcript of speech delivered at Los Angeles, California, 1972, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27328.

[9] Laura Johnston Kohl. Jonestown Survivor: An Insider’s Look. (New York: iUniverse, 2010), 28.

[10] Guinn, Road, 72.

[11] Jim Jones, “God Saves Lives Through Picture,” The Living Word, July. 1972, 28.

[12] Jones, “God Saves,” 4.

[13] Jones, “God Saves,” 22.

[14] Guinn, Road, 83.

[15] Interview with Fielding McGehee.

[16] Guinn, Road, 92.

[17] Guinn, Road, 115.

[18] Jonestown Death Tape, transcript of speech delivered at Jonestown, Guyana, November 18, 1978.

[19] Mary McCormick Maaga. Hearing the Voices of Jonestown. (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1998), 89.

[20] Johnson.

[21] Barbara Walker, “The Front Line in Ballad and Thought”: Poetry, 1977. (accessed 20 Jun 2023)

[22] Joel Greenberg, “Jim Jones: The Deadly Hypnotist,” Science News, Society for Science & the Public, Vol. 116, no. 22, (Dec. 1, 1979): 378-379, 382.

[23] Bekithemba Dube, Milton Molebatsi Nkoane and Dipane Hlalele, “The Ambivalence of Freedom of Religion, and Unearthing the Unlearnt lessons of Religious Freedom from the Jonestown Incident: A Decoloniality Approach,” Journal for the Study of Religion, ASRSA, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2017): 336.

[24] Judith Mary Weightman, Making Sense of the Jonestown Suicides: A Sociological History of Peoples Temple. (New York: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1983), 114.

[25] Weightman, Making Sense, 95.

[26] Dube, et al., 335.

[32] Annie Moore’s Last Letter.

[33] Rebecca Moore, A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in Peoples Temple. (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1985), 286.

[34] Weightman, Judith M. “The Peoples Temple as a Continuation and an Interruption of Religious Marginality in America.” In New Religious Movements, Mass Suicide, and Peoples Temple: Scholarly Perspectives on a Tragedy, edited by Rebecca Moore and Fielding McGehee III, 5-22. (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1989), 19.

[35] Guinn, Road, 88.

[36] Guinn, Road, 89.

[37] Rebecca Moore. “What is Apostolic Socialism?”. November 9, 2018. (accessed June 25, 2023). https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=84234.

[38] Guinn, Road, 172.

[39] Moore, “Apostolic Socialism.”

[40] Klippenstein.

[41] David Chidester. Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown. (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2003) 5.

[42] Jeff Guinn, Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014), 114.

[43] Duchess Harris and Adam John Waterman, “To Die for the Peoples Temple Religion and Revolution after Black Power” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004), 110.

[44] Klippenstein.

[45] Johnson.

[47] Guinn, Road, 290.

[48] Phil Blakey. “Snapshots from a Jonestown Life.” Jonestown Institute, September 25th, 2018. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=81310 (accessed June 20, 2023)

[49] Johnson.

[50] Carolyn Layton Moore to John and Barbara Moore, October 11, 1977, Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple.

[51] James T. Richardson, “Peoples Temple and Jonestown: A Corrective Comparison and Critique.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 19, no. 3 (1980): 249 https://doi.org/10.2307/1385862.

[52] Guinn, Road, 311.

[53] Guinn, Road, 328.

[54] Greenberg, 378-379, 382.

[55] Guinn, Road, 311.

[56] Chidester, 159.

[57] Ethan Feinsod. Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown the Only Eyewitness Account. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981), 170-171.

[58] Guinn, Road, 67.

[59] Guinn, Road, 66.

[60] Guinn, Road, 67.

[61] Rebecca Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004), 57.

[62] Stephen C. Rose. Jesus and Jim Jones. (New York: Pilgrim Press, 1979), 19.

[63] Jim Jones, “To All Man Kind,” The Open Door, April. 1956, 3.

[64] Smith, 48.

[65] Smith, 52.

[66] Harris and Waterman, 120.

[67] Milmon F. Harrison, “Jim Jones and Black Worship Traditions” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004), 135.

[68] Harrison, 129.

[69] Harrison, 136.

[70] Smith, 51.

[71] Eric C. Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya, “Daddy Jones and Father Divine: The Cult as Political Religion,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004), 41.

[72] Guinn, Road, 104.

[73] United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. RYMUR 89-4286-HH-6-A-2, 1975, California.

[74] Guinn, Road, 94.

[75] Wessinger, 39.

[76] Moore, “Demographics,” 58.

(Alex Jung is a student at Li Po Chun United World Colleges in Hong Kong. He is conducting interviews and writing articles regarding Jonestown, including interviews with Fielding McGehee III and Stephan Jones, both in 2023. He may be reached at ttjabhhsm@gmail.com.)