(This article is excerpted and adapted from “Songs Primarily in the Key of Life”, Colorado Review (Vol. 37, No. 2, Summer 2010, 68-101). The original essay was accepted as the author’s MFA thesis in creative nonfiction at the University of Montana. Brian Kevin can be reached at brikevin@gmail.com.)

(This article is excerpted and adapted from “Songs Primarily in the Key of Life”, Colorado Review (Vol. 37, No. 2, Summer 2010, 68-101). The original essay was accepted as the author’s MFA thesis in creative nonfiction at the University of Montana. Brian Kevin can be reached at brikevin@gmail.com.)

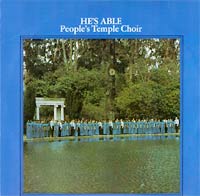

One of my favorite records lately is a light funk-gospel album recorded in 1973 by the world’s most infamous suicide cult. It’s a twelve-song collection, a mix of old spirituals, gospel-inspired originals, and a couple of late ’60s Top 40 hits, all performed by a full choir and an eight-piece blue-eyed soul outfit with a hot brass section. On the record jacket, the album’s title is printed in austere white lettering: He’s Able. The name comes from the chorus of an old revival-tent anthem, a sultry little call-and-refrain number that leads off the record’s B-side. It’s the kind of song you might hear one Sunday morning in the Deep South, the kind that’s sung in a sunlit place where the women carry fans and the air is heavy with hallelujahs.

On the album’s cover photo, we see the choir standing on the far side of a small pond, ninety or so people bunched along the shore, facing forward, small and individually indistinct against a wooded background. The women wear plain aqua-blue gowns, and the men are in black pants with light blue oxfords and dark ties. Racially, they’re a mixed bag, about equal numbers black and white. I count no fewer than fifteen afros, hovering like halos around dark, smiling faces.

Although the photo shows the full chorus, not all of the choir members actually sing on the album – just a couple dozen. Their voices were multi-tracked in the studio, then played back on top of one another in order to give the impression of a fuller chorus.

There are several small photos on the back of the jacket, including another shot of the choir, this time crowded onto a wooded path. Their arms are raised above their heads in what looks like praise but could just as easily be surrender. In another photo is a young white man, handsome in a suit jacket and tie, his black hair parted neatly to the side and glistening slightly with pomade. He stands at a lectern with his eyes cast downward, his right hand resting casually along its wooden edge. The look on his face is serene and coolly regal, like that of a general before his troops. He’s clutching an object that’s half-cropped out of the photo and difficult to identify. If we look very closely, we can see that it’s a pair of dark sunglasses.

Beneath the photo is a caption: “Our choir consists of people from all walks of life. We are dedicated to one common cause – making the humanistic teachings of Jesus Christ part of our daily lives. Our inspiration is a lifestyle demonstrated by our pastor, James W. Jones.”

He’s Able is out of print. Has been since 1978, when most of the singers and musicians featured on it killed themselves in the jungles of Guyana by drinking cyanide-laced Flavor Aid in what has come to be known as the Jonestown Massacre.

* * * * *

Only about twenty-five kids made it onto the He’s Able record album. We can see them in a series of photos on the back of the record jacket, a gaggle of multiracial children between four and twelve years old. They’re wearing earphones, facing a set of area mics, standing and squatting and grinning wildly in the manner of an elementary school class photo. The setting is a Los Angeles recording studio called Producer’s Workshop. Long-since closed, the studio was a low-rent, ground-floor affair, wedged next to an X-rated theater on a dicey stretch of Hollywood Boulevard. Its youngest sound engineer in 1973 was a twenty-year-old techie named Bob Schaper, whose lack of seniority got him assigned to man the boards during the half-dozen Saturdays of cut-rate, after-hours sessions that resulted in He’s Able.

Schaper still recalls the pandemonium the night the kids’ choir came in to record “Welcome.” Producer’s Workshop was a real geek’s lair, a cramped and cluttered dungeon with a nonetheless killer recording set-up. It was ornamented humbly with ashtrays, carpet squares, and LP covers. The studio lacked room for even a couch or a coffee maker, much less a thirty-child chorus, so between takes, the kids would fan out across the tiny complex in search of sleeping space. They sprawled in cabinets, hallways, and bathrooms, piling up on every available surface like the cigarette butts overflowing the ashtrays.

“There were just so many bodies,” Schaper says, innocently. “Everywhere I looked there were children’s bodies.”

This is an unfortunate turn of phrase, as it inevitably calls to mind the more than 300 children who were fed potassium cyanide when Peoples Temple self-destructed. It’s a common problem when discussing the Temple: Even in a context that ostensibly avoids the topic of Jonestown, the 918 people who died there linger behind every conversation like the barely heard remnants of a root language. It’s difficult to talk at length about the church, its members, or its history without stumbling blindly into some sort of grisly double entendre. But this difficulty is also a central part of what makes He’s Able such an enigmatic artifact.

* * * * *

Far and away, my favorite track on He’s Able is “Walk a Mile in My Shoes.” It’s the record’s first cover, a hot-buttered soul spin on the Joe South country rock tune that reached #12 on the pop chart and eventually fell into Elvis Presley’s Vegas repertoire. This kind of dabbling in the Top 40 canon was common in Peoples Temple liturgy. Their typical songbook looked like a cross between a Baptist hymnal and a playlist on the oldies station, accommodating, for example, Burt Bacharach’s “What the World Needs Now” and Bob Dylan’s “Blowing in the Wind.” Still, it’s not the song choice that makes this track a winner. It’s the singer.

Melvin Johnson was twenty-five years old and living on the streets in San Francisco when a shoestring cousin brought him to Peoples Temple in 1969. He’d spent most of his young adulthood behind bars, with stints as a pimp and a drug dealer between incarcerations. With a daughter in foster care, a set of parole papers, and nothing to lose, Johnson gave himself to the church. He became a constant presence at the San Francisco temple, volunteering as a driver for the Temple’s bus fleet and eventually joining the choir. He found a job driving cab, and he saved his paychecks while members in the Temple communes signed theirs over to the church. Most importantly, Peoples Temple gave Johnson a family again. By the time he was singing on He’s Able in 1973, Melvin Johnson had married long-time Temple member Wanda Kice. And not only was his daughter back in his life, he had three new stepsons too, from Wanda’s previous marriages.

But the singer who pours himself into the mic on “Walk a Mile in My Shoes” is no work-a-day churchgoing family man, no meek Sunday-morning Joe. From the second he lets loose with his first melodic moan – a velvety oooh yea-eah-eah – you can tell that this is a brother who’s been there. Somebody who’s worn a pair of shoes you might think twice about stepping into. Johnson’s got pipes, channeling a non-falsetto Al Green when he sings lines like:

Well, I may be common people but I’m your brother

and when you strike out and try to hurt me, it’s hurting you.

As a listener, you just can’t help but buy it. You can’t help but think that this is a guy who believes every word he’s singing, that the lyrics mean more to him than they did to Joe South or Elvis. Even Johnson’s breathy vocalizations come from someplace deeper than those of any polished radio crooner. The band is cooking too, and musically, this rendition gives the others a run for their money. It’s a straight-up specimen of authentic soul, and it banishes for a time even the hint of a thought about Kool-Aid or cults or bodies piled up in the jungle.

That’s what’s ultimately so impressive about the church-choir proto-funk on He’s Able. You put it on bemused, expecting some sort of haunting historical document. Then you press play, and the music comes at you like a confetti explosion, all crashing piano chords and fret-shimmying electric guitar. And you don’t hear a group of religious fanatics whose zealotry will culminate in the Jonestown Massacre. You don’t hear a cult at all – just a great gospel-rock band and choir who sound like they’re having a hell of a time.

Which is kind of a big deal, when you figure that there are stacks of Peoples Temple literature out there devoted to drumming up just that kind of empathy. Since Jonestown, dozens of books, articles, documentary films, and even theatrical plays have attempted to fix their audience’s gaze beyond the Jonestown suicides, banishing the image of the cult in favor of portraying real people with real motivations. It’s just a tough cerebral move to make, blocking out all those corpses in order to understand the Temple members as something other than sinister zombies or tragic sheep – as passionate, fallible, well-intentioned individuals.

But put on the record and play a couple of tracks, and with the right kind of ear, you understand it instantly. All that good intention, all that humanity that struggles to make itself known in the books and the movies, you can hear it plain as day in the first up-tempo boogie-oogie piano scale; you can hear it in the tinny snare rolls of an overeager drummer, you can hear it in the cool, throaty mmm hmmms and oh yeahs of a riffing soloist. It’s all right there – everything that drew these people in, everything they wanted to accomplish, everything they failed at. It comes out of your stereo speakers like a sunbeam through a stained-glass window. And it sort of breaks your heart.

(The music of He’s Able may be found online here, listed by song title in the third paragraph.)