California Historical Society

(Author’s note: This paper is the result of my Bachelor thesis in Psychology at the University of Oslo, Norway, class of 2006. I became extremely intrigued by Peoples Temple and its history after reading about its fate in Cults and Religious Movements, edited by Lorne L. Dawson. It was both a bit terrifying and thought-provoking to work on this paper, and had I the time, I would have written an article that would go even deeper into the processes that led to the tragedy in 1978; a single paper of this size simply cannot give justice to the complexity that surrounded Peoples Temple.

(A Bachelor’s thesis in Norway is a student’s first taste of writing an article where the goal is to use already existing material and combine this in a new way (my impression was that topic indeed was a first-timer at my University). I worked under both time and page number restrictions, but in the end I felt pretty happy about the result (it was awarded second best grade). Nevertheless, I gained some valuable insights into human weaknesses and strengths, an insight that I hope to carry with me further into my studies. I was admitted to the cand. psychol. course autumn 2007 at UiO, and I will graduate in 2013 as a psychologist.

(This essay was a gentle probe into the art of writing and the often tedious work of gathering and screening difficult material. But the experience proved to be a valuable one. Peoples Temple and the various writings at this website have left an impression I will never forget.

(I may be reached at aksvendsen@hotmail.com.)

Introduction

Who wants to go with their child has a right to go with their child. I think it’s humane. I wanna go… I want to see you go, though. They can take me and do with me whatever they want to do. I want to see you go. I don’t wanna see you go through this hell no more. No more, no more, no more.

– Jim Jones (Q 042)

This was uttered by one of history’s most notorious charismatic leaders just moments before he guided more than 900 of his followers to their deaths. Where the previous so-called White Nights in Jonestown had merely been practice runs for the mass suicide/murder that would happen November 18th, 1978, the last White Night the members would experience would prove to be deadly serious. Peoples Temple and the tragedy at Jonestown, Guyana, is one example of a new religious movement where things went very wrong. It is however in such extreme cases one can observe the theories of social psychology made explicitly manifest. The processes that lead to such extraordinary behavior are many and extensive, and this article will try and shed some light on some of these processes through the application of social psychological theories.

Throughout the history of social psychology, there has been considerable research regarding social influence, especially how the group influences the individual and how the individual influences the group. This process is reciprocal. Asch’s (1951) classic experiment demonstrated the powerful influence the majority can have on the individual when the latter is experiencing a stressful situation where his or her observations are experienced as inconsistent with the group. Despite the individual’s often strong doubts regarding the group’s decision, 37% of their answers conformed to the majority (Asch, 1951). These findings can be transferred to “cults” where the individual will come to experience the power of conformity within a closely knit group. Even if the individual has doubts about the movement’s beliefs and practices, it can be hard to speak up when everyone else seem to have a differing opinion. Stanley Milgram’s well-known obedience experiments also focused on the power an authority figure can exercise on the individual, and this becomes relevant in the relation between charismatic leader and his followers. The central focus of this article will be to demonstrate which social psychological processes are expressed in a new religious movement such as Peoples Temple. When more than 900 people go to the extreme and take their lives together with their leader, it becomes clear that something must have happened to these people after they became members of the movement. It is sensational how irrational these groups and their rhetoric come across to outsiders, while in the meantime being so meaningful for the people belonging to that particular group. What methods do charismatic leaders such as Jones put to use to command the group’s loyalty? These questions can be illustrated with the help of social psychological theories on leadership, power, persuasion, conformity and obedience. Jonestown provides a good example on how we are influenced in an extreme situation, as well as what the possible consequences can be when a charismatic leader uses his influence and his power to destructively manipulate other people’s behavior.

The reason for choosing Peoples Temple as a case in this paper is that its history is so extreme that the social psychological processes become largely visible. Many of the theories we use in today’s social psychology have come to life through laboratory experiments. To witness these in a natural setting is both fascinating and terrifying. New religious movements have in the last years received a great deal of attention in the media, often due to negative incidents such as suicide and reports of leaders using techniques of “brainwashing” to hold members against their will.

It should be made clear at the beginning that there is only a very small part of the new religious movements that can be associated with the above, and that Peoples Temple was chosen because it is a very information-rich case. The theme of this article is also relevant in our own time. We don’t have to go any further back than to the 1990’s to find cults that ended in mass-suicide: the Order of the Solar Temple in Switzerland and Canada in 1994, the Branch-Davidians in Waco, Texas in 1993 and Heaven’s Gate in California in 1997 (Dawson, 2003). We have to be prepared that similar incidents can happen again; therefore it is important that we focus on these movements in a social psychological connection where the main interest should be the situational processes, not the individual. In that way we can learn to understand how mass-suicide can happen in certain groups.

The article will put to use material that is available on the tape section of this website. The material consists of transcripts and tapes that were recorded by Jim Jones himself during the many sessions he had with his followers in Jonestown. This material can help illustrate the social psychological theories in a new and exciting way because it has not been processed and reviewed beforehand, but stands today as it did for the members of Peoples Temple thirty years ago.

Cult – a definition

The word “cult” has been associated with negative phenomena such as brainwashing and mass-suicides, which in turn has led to a change in the terms used by researchers in this field. It was cases such as Jonestown that initiated the negative rhetoric associated with “cults” due to its macabre history. Today’s most commonly used term in the science of religious studies is New Religious Movements, or NRM, which this paper will also put to use. “Church”, “sect and “cult” should be separated from each other in a paper such as this. “Church” is usually applied to religious, often conventional, organizations. A “sect” is an offshoot from a specific religious organization where the members follow a different doctrine than its Mother Church. A “cult” has several of the same characteristics as a sect, but in addition it includes for the members a sudden separation with their past as well as people in their lives who are not members of the cult. Cults are often recognized by members that hold a strong commitment towards a charismatic leader, and often their unconventional beliefs can result in a tense relationship with the rest of society. Some cults encourage their members to break away from their family and friends to allow them to dedicate all their time and energy to the group (Hunter, 1998). According to this definition, Peoples Temple can be described as a cult.

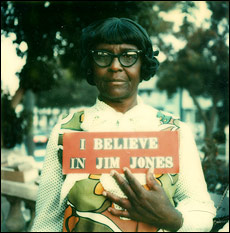

Jim Jones and Peoples Temple – a historical overview

To better understand the processes that lay behind the formation of the Peoples Temple and its dramatic ending, it is necessary to provide some information on their leader Jim Jones as well as the events that took place before the mass-suicide in Guyana, 1978. This paper will emphasize that Peoples Temple attracted normal people that together shared a hope of a better world. Eventually pressure from the established society and media drove the group out of the U.S. to the jungle of Guyana. This next section summarizes the history of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple.

James Warren Jones was born in 1931during the Great Depression in Indiana, where he grew up with a great distaste for people of wealth, status and privilege. Jones was exposed to Christian Protestant movements, but it was the Pentecostals that notably impressed him by their glossolalia and religious enthusiasm. Jones started to preach on his own during his twenties. Inspired by the Pentecostals doomsday visions as well as the Methodists communistic ideals, he promoted racial integration combined with a communistic philosophy while offering faith healing to those that were intrigued by his speeches. On several occasions his healings were revealed as nothing but a hoax, but his astonishing ability to speak to his public made him grow in popularity (Hall, 1987). In 1953 Jones founded a small church in Indianapolis called Community Unity which gradually turned into a communal socialist movement. Jones moved from being an unconventional preacher to a prophet who voiced warnings of a capitalistic apocalypse where those that heeded his words would gain entry into the promised socialistic land; a place where they would survive the destruction of the world (Hall, 1987). The structure of his church became increasingly patriarchic, and his followers started addressing him as “Father” or “Dad”. Jones demanded absolute obedience from his members. He introduced a rule of taxes that would be paid by deducting a certain amount from the members’ payrolls and transferring them to the church’s holdings (Osherow, 1995). In 1964 Jones was officially ordained by the Disciples of Christ denomination, and in 1965 he moved his church to California due to fears of nuclear war and what Jones deemed to be strong racial intolerance in Indiana. In California, Peoples Temple attracted members from every walk of life, including blacks, Asians, hippies, fundamental Christians, militants and elderly people. This led to a rapid growth of the organization. Peoples Temple was active in the left-liberal wing in California, and the Church influenced the election of Democrat George Moscone as Mayor in San Francisco in 1975. Jones was in return given a position in the city’s Housing Authority Commission, and he enjoyed good remarks in the media.

Relocation to Guyana

Despite the positive attention in the press, everything was not well in Peoples Temple. In 1977, the magazine New West printed an article that was largely influenced by the anti-cult attitudes that had started to develop at that time. Former members of the Peoples Temple interviewed for the article said that financial fraud, physical abuse and brainwashing all took place within the movement (Hall, 1987). This, combined with a fear of government investigations of their tax-exempt status, led to a strong pressure that would eventually lead Peoples Temple to Guyana. The collective migration to Jonestown begun in 1977, and by 1978 the small community consisted of about a thousand people, 70% of whom were black (Hall, 1987).

In 1978, Congressman Leo Ryan went to Jonestown together with a press contingent to investigate the conditions in Jonestown, following up on allegations that members were being held there against their will. The anti-cult movement Concerned Relatives had for some time tried to get the government to investigate Jones, as well as the methods he used to keep members under his control. During the team’s stay in Jonestown, which lasted one night and the beginning of the following day, Ryan mostly met with content members who praised Jonestown and expressed their wishes to stay. Sixteen people, including members of two families with long histories in the Temple, told Ryan they wanted to go back to the US with the delegation. This had an infuriating effect on Jones. A short while after the delegation took their leave from Jonestown and went to the airstrip in Port Kaituma, they were attacked by gunmen belonging to the Peoples Temple. What remained behind were the bodies of five people: Congressman Leo Ryan, three reporters and a Peoples Temple deserter named Patricia Parks (Hall, 1987).

At the same time that the shootings at the airstrip took place, Jones gathered his congregation for their last “White Night”, which they had practiced several times before. Large vats with the fruit punch Flavor Aid mixed with cyanide and valium was placed in the pavilion where the community was gathered. The deadly cocktail was given to babies first by adults pouring it into their throats. Afterwards, elder children together with the adults queued up to drink the poison. Families walked hand-in-hand to die after being downing their cups. It should be noted, however, that evidence points towards some members being forced to drink the poison (Barker, 1986). In the aftermath of the last White Night lay 909 dead, including Jim Jones himself. Among the dead almost 300 were under the age of seventeen. Counting the victims at Port Kaituma and four others who died in Guyana’s capital city of Georgetown, the Jonestown tragedy claimed 918 lives.

Causes of the mass suicide in Jonestown

The big question in the aftermath of Jonestown was “how could this happen?” That over 900 people chose to die together with their family members and friends was something that for outsiders appeared incomprehensible. The Concerned Relatives seemed to be right in their worries that Peoples Temple was a destructive NRM, but it would be too simplistic to say that the people in Jonestown committed this act of suicide/murder as a result of being kept in Jonestown against their will, or that they had all been brainwashed. These means for explaining what happened in Jonestown greatly underestimates the social influence and the strong effect this can have on people living under certain conditions.

There seem to be a belief held by many people that individuals who choose to commit suicide in a group must be crazy, pathological and weak. Earlier studies have shown that when people are asked to describe the participants in Milgram’s obedience experiment, they have been quick to characterize them as aggressive, cold and unappealing, because we tend to draw the conclusion that no “good” person would inflict pain upon others (Myers, 2004). The situational factors have a tendency to be ignored; we put all responsibility on the individual and attribute his actions to his or her personality. In theories of attribution this has often been called the Fundamental Attribution Error, first demonstrated in a classic experiment designed by Jones and Harris (1967). In this experiment, participants were asked to decide whether the author of a speech on Castro had positive or negative feelings towards Castro on a personal level. Even when the participants were informed that the stand taken in the speech, be that negative or positive towards Castro, was not optional but rather the result of an assignment, the participants still answered that the author had a positive view on Castro had he performed a positive speech, and vice versa. Hence, they underestimated the importance of the situational factors when choosing to focus on the disposition of the author, which in this case, was not relevant (Jones & Harris, 1967).

To avoid this attribution error when trying to explain the mass suicide in Jonestown, we have to look at several points extending beyond the mere personality of the members of Peoples Temple. One of the goals in this paper is to remove that focus from the individual alone and rather look at the situational factors that seem to have played a significant part in this tragedy. Here are some main points that seem to be of relevance:

• A charismatic leader who mastered and put to use several well-known psychological methods to ensure that his members remained loyal and obedient, while at the same time using medications that resulted in a growingly paranoid psyche, which in turn would affect the people around him.

• The relocation of Peoples Temple to the isolated rural community that was Jonestown, Guyana.

• The group’s impending fear of the final destruction of civilization, combined with the murder of Congressman Leo Ryan.

• Powerful opposition and perceived threat outside groups such as anti-cult movements, the media and the US Government.

These are all situational factors. This paper will intentionally avoid an explanation based on the member’s personality alone, simply because it does not seem to be relevant for what happened in Jonestown. Of the 909 people who died in Jonestown, there were fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, doctors, teachers, blacks and whites. They represented all classes of American society. What they had in common was a socialistic ideology that aimed for equality and a better world to live in. They were not crazy, mentally ill nor weak individuals; they all became the victims of situational influence as well as of a powerful leader which in combination would prove to be fatal

Jim Jones, power and leadership

Jim Jones was the People Temple’s undisputed leader from its beginning to its tragic end in 1978. After the news of the mass-suicide reached the public, he went from being a visionary spiritual leader to being called everything from a psychopath to Anti-Christ himself (Hall, 1987). There is little doubt that Jim Jones wielded an enormous influence and power over his followers, or that he played a crucial part in the mass-suicide in Jonestown. The question one may ask, however, is how certain leaders like Jim Jones gain such power and how they can influence their followers to such a large extent that they go to such extremes and take their own lives when encouraged to do so.

Charismatic leadership

As mentioned before, Jim Jones was a person who, despite of revelations of false faith healings, managed to capture his listeners in a fascinating and effective way. It becomes essential to look at the dynamics between the charismatic leader and his followers to understand what led to such a destructive regression that was witnessed at Jonestown. Jung (Jung in Ulman & Abse, 1983, p. 639) wrote the following:

There is one simple rule that you should bear in mind; the psychopathology of the masses is rooted in the psychology of the individual. Psychic phenomena of this class can be investigated in each individual. Only if one succeeds in establishing that certain phenomena or symptoms are common to a number of different individuals can one begin to examine the analogous mass phenomena.

It was the sociologist Max Weber who first used the term charisma to describe the irrational affection that followers sometimes showed towards their leaders (Forsyth, 2006). Weber argued that charismatic leaders do not have special powers as such, rather that their success is a result of their followers actually believing that they do possess special powers, and that it is their leader’s destiny to guide them to the right path of living. Weber narrowed down the term so that it described leaders who appear as saviors in a time when certain people feel unsatisfied with their position in life. The charismatic leader can then assume the role as savior whose task is to provide the searchers with a solution or cure that will remove their problems. The result is often that the followers express an intense loyalty towards this leader (Forsyth, 2006). Jones fits perfectly into this category. The racial differences and the debate over equality in America were still very much alive during the 1970’s. Jones preached of equality and the establishment of an Utopian society in which everyone would be of same worth no matter their race and background. Laura Johnston Kohl, an ex-Temple member, said this in an interview with CNN (2003):

Well, when I went into the first service with Jim Jones, he had pulled together people from every walk of life, of every color. And we had progressive people who were involved and we supported progressive causes. I thought that it was really a way to speak out as a group and try to make the world a better place.

According to Tucker (Tucker in Ulman & Abse, 1983), it is not only the leader’s personality that is important, but also the historical and socio-economic factors. A leader such as Jones must have been very appealing to blacks who came from a lower class in society, as well as for those who desired equality among people of different color in the US. In other words, Jim Jones appeared as a leader who would free his followers from something they saw as an individual existence filled with frustrations; he seemed to his group of followers a man of power who had visions and dreams that fitted very well with their own.

Ulman and Abse (1983) take a psychoanalytical perspective in their analysis of Jonestown. They point at different studies done on several well-known charismatic leaders such as Hitler, Stalin and Gandhi, where the results show strong correlation between the charismatic leader type and the narcissistic personality type. Jones too seems to might have had narcissistic tendencies. He was very preoccupied with the theatrical and dramatic aspects of his ministry. Several times during public appearances, Temple members he planted among the audience would shout positive comments. David Parker Wise, a former pastor of the Temple, said the following of Jones’ methods: “Of course, it was a big help to train everyone else to walk behind you and make a big racket over your every gesture. Having a few people ‘drop dead’ is a powerful thing too” (Wise, 2003, no page number). It is obvious that Jones went to extremes to preserve the Temple’s reputation whenever he appeared in public, as well as doing his very best to maintain his own grandiose self-image where the façade of his absolute confidence would not be revealed. A transcribed tape recorded in Jonestown 1978 describes Jones preparing his congregation for a visit from the press. He prepares them so that they will answer questions in the best possible way regarding his healing sessions, how they are treated in Jonestown and how much they would like to keep living their lives there. He also instructs them how they can shape their answers so that the movement doesn’t get negative press attention:

Woman 5: Mostly everybody here doesn’t want to return to the States ‘cause they enjoy–

Jones: I would say–

Woman 5: –they enjoy Jonestown.

Jones: I would say – that’s okay – I would say I don’t know anybody here that wants to go back. Don’t say “mostly,” ‘cause then they’ll start you open another one. Say, I don’t know anybody here that wants to go back. You understand?

Woman 5: Yes, Dad. (Q 49 (Part 1)

This is one of many tapes that illustrate Jones’ all-embracing power over the group.

The article will now take a closer look at theories on power, and attempt at understanding how Jones attained such power.

The six bases of power

John R. P. French and Bertram Raven summarized many of the fundamental sources of power in 1965 when they presented the six bases of power as an explanation for social influence in groups (Raven, 1993), and it is interesting to apply their theory to Jim Jones’ position in Peoples Temple. Jones’ leadership style can be described as charismatic in a sociological tradition, but there seem to be other aspects that also were important when trying to explain how he attained such power over his followers. We take a step away from the individual-focused charismatic theory and instead look at a situational model of Jones’ leadership.

The first base French and Raven describes is founded on reward. Power is often associated with control of resources, and a person who controls resources and their distribution will often gain a position of power in the group. In Peoples Temple, Jones was in possession of things that people desired, be that security, economical support, social support, political ideas or spirituality (Forsyth, 2006). For many people, he was even a prophet who held the key to a communistic and egalitarian Utopia on Earth. In other words, Jones had reward power over his group.

The second base of power is associated with coercion and threats (Raven, 1993). In this sense, a leader attains power over a group by punishing, humiliating or shunning individuals who break rules that the group is expected to follow. Jones was known to use several punishment strategies before they left for Jonestown and especially during their stay in Jonestown. Physical and psychological punishments were used, combined with isolation of rebellious members and days of long, hard work in the fields (Hall, 1987).

The third base French and Raven named legitimate power. Individuals who possesses legimate power are considered rightful leaders due to their position within the group, and thus they have a recognized right to ask others to follow their orders. When people joined Peoples Temple, Jones was the uncontested leader whom they willingly chose to follow. He embraced the role as a father figure and a prophet for his group. This type of power is considered the most apparent of the original five, and also the most important.

The fourth base describes referent power, and is closely tied to how a charismatic leader gains influence over a group. This base refers to individual power gained due to the group’s intense identification with, attraction to, and respect for the power holder (Raven, 1993). Several members of the Peoples Temple were so dedicated towards Jones that, in hopes of pleasing him, they transferred their belongings to him when they joined the movement. Jones’ role as savior whose task was to improve the members’ current situation must have undoubtedly led to an intense identification with, and attraction to, his person.

The fifth base refers to expertise held by the power holder. Group members often follow people who seem to be in possession of superior skills and knowledge (Raven, 1993). Like charismatic leadership, the essence in this base is not whether this person actually possesses these skills and knowledge, but whether the group believes that he or she does. He or she does not in fact have to be an expert as long as there is an illusion of expertise that the followers accept. Jones demanded that his followers call him “father” or “dad”, something that helped him acquire a special status within the group. On several tapes where Jones is faced with a dilemma that he cannot or will not face, he is quick to state that his actions are justified due to his status as a prophet, and that he, being sent by God or even being a reincarnation of Jesus or Lenin, knows what is best for the group (varied tapes, also Q042). As long as the group accepts his claims, he will keep his position as an expert in the group, and hence his decisions will be considered legitimate.

The last base was added by Raven in 1965, and is called informational power (Raven, 1993). This means that a leader can delegate information to those that need it, keep it from them if he so chooses, or even falsify the information before it reaches his followers. When Peoples Temple relocated to Guyana, the group became isolated. Laura Johnston Kohl (2003), a survivor from Jonestown, describes it this way: “and except that Jim was getting sicker, going crazier and crazier, and all of us isolated, all the people who lived in Guyana only heard what was going on in the world through Jim.” Thus, in combination with all the other bases of power, Jones was the only person with the power to decide what information that was to be given to the people of Jonestown.

When French and Raven’s model is applied to the leader Jim Jones, it becomes obvious how many different strategies he used to maintain and justify his power over his group. It is often the referent or the charismatic aspect that gains most attention when studying leaders like Jones, but it is apparent that his power lies on different levels, not just one. This fact contributes to his flexibility as a leader as well as gives him the opportunity to face challenges with several different strategies during his time in Jonestown.

The Power of the Situation

In the period following the Jonestown tragedy, Jones – the self-proclaimed Messiah – was presented by the media as a manipulating, evil and narcissistic person who had tricked credulous “fanatics” to their deaths (Osherow, 1995). The focus still remained heavily on the leader’s personality and on the victims’ weaknesses. Even though this approach certainly can provide us with valuable information, it is often too one-sided to provide give us a view of the whole picture. There are other factors that are just as important that should not be ignored. As previously mentioned, people often stumble into a phenomenon that theorists such as Lee Ross (2001) later would call the fundamental attribution error (FAE). Even though it may be tempting, and perhaps to a certain degree comforting, to think that people who commit collective suicide are both crazy and possess weaknesses the rest of us do not have, it is often far from the truth. It is important to stress the significance of the social context in a phenomenon such as Jonestown. The chain of events before the suicides can be illuminated especially by two social psychological theories, namely persuasion and conformity, two powerful processes that can lead to tragic events on special occasions.

Persuasion – a powerful psychological weapon

Richard Petty and John T. Cacioppo’s (1984) Elaboration Likelihood Model was developed as an attempt to explain the human cognitive reactions on persuasion. This model presents two ways in which people can be persuaded. The first is the central route where persuasion is based on an analytic and involved audience that is focused on discussing the allegations being presented. The second route, called the peripheral route, is based upon little to no cognition among the audience who display little involvement in the matter at hand. Further, the peripheral route puts to use simple heuristics such as trusting the expert simply because he or she is presented as such without analyzing the message that is being put forth on its own.

Jim Jones directed himself to people from every walk of life in the American population, but the main population in Peoples Temple were Afro-Americans from the lower end of the socio-economic scale. Potential new members were overwhelmed by the sight of people of different color who worked, lived and prayed together, and new recruits were exposed to so-called “love bombing” where members overwhelmed them with warmth and interest (Osherow, 1995). New recruits also became witnesses to Jones’ healing performances, during which he claimed to remove cancers by reaching with his hand into the patient’s throat and pulling the tumor out (the tumor later turned out to be a chicken’s gizzard or liver). Other methods that would appear impressive to new potential members was when Jones described their homes or the menu at their latest dinner with surprisingly good precision:

Have you ever seen me before? Well, you live in such and such a place, your phone number is such and such, and in your living room you’ve got this, that and the other, and on your sofa you’ve got such and such a pillow… Now do you remember me ever being in your house? (Myers 2004, 164)

Jones had coworkers who called at the potential recruits’ homes, and asked detailed questions in the cover of doing an unrelated examination. This provided Jones with inside information that would make him seem clairvoyant and being in possession of superhuman powers. These “revelations” did indeed have such a strong effect on some recruits that he was considered a savior and even Jesus made manifest. These methods are placed under the peripheral routes to persuasion. It was Jones’ charisma and role as prophet that weighed most heavily as heuristics, and they overshadowed the audience’s own critical thinking to a large extent. When the Temple migrated to Guyana, the residents of Jonestown worked long days in the fields, often from early in the morning to late at night. This undoubtedly must have led to exhaustion and fatigue, something that has proven to lower the defense mechanisms that normally work against persuasion. It also lowers the chance of making counter-arguments against the persuader (Myers, 2004). When tired, one seldom takes the effort to engage in deep cognitive analysis, thus one is more likely to accept the message as it is being presented. An audience with a high education is more susceptible to rational appeals than an audience with little or no education (Myers, 2004). The majority of Jones’ followers belonged to the latter group, and they acknowledged the simplicity of his message. It leaves us however with one question that should be answered: how could it be that those who indeed had a background of higher education let themselves be convinced of Jim Jones’ message?

It was the individuals with a higher degree of education who would become part of the inner circle of the Peoples Temple’s power structure, and it seems that these people were persuaded by different things than Jones’ sensational demonstrations of healing. Most of these people hailed from the upper middleclass, and consisted of lawyers, medical students, nurses and other professions that required a somewhat higher education (Osherow, 1995). This group was drawn to Peoples Temple as a political and ideological movement, the uppermost goal of which was a Utopia where people from every walk of life could coexist together. These people understood very well that Jones’ spectacular healings and psychic readings were just a façade, but they accepted them because they were necessary for the Cause, their superior goal. Jeannie Mills was one of the people who rationalized her doubts: “If Jim feels it’s necessary for the Cause, who am I to question his wisdom?” (Mills in Osherow, 1995). It is interesting to note that the two social strata of Peoples Temple was drawn to the movement in different ways, and that Petty’s Elaboration Likelihood Model can be applied as an illustration in this context.

The foot-in-the-door phenomenon – gradual commitment

Why and how people become attracted to NRMs can be illustrated with the foot-in-the-door phenomenon. Developed by J. L. Freedman and S. C. Fraser (1966), this theory is based on the fact that we are more likely to agree to do an extensive favor for someone if we have agreed to do a smaller favor beforehand. If you are to persuade someone, you would be better off to gradually increase the demands instead of asking for a comprehensive favor at once. Jim Jones also put to use this strategy to recruit people into his movement, and when they became a part of Peoples Temple, it was also used to make them stay.

One example of this involves the assets the members transferred to the church. In the beginning, people voluntarily donated money, but after a while Jones implemented a forced donation regulation that constituted ten percent of the member’s income. At a later point, this was increased to an obligatory twenty five percent. In the end, Jones ordered that all of the members’ assets must be handed over to the movement. As a result, most of the members who went to Jonestown had lost most, if not all, of their belongings. Grace Stoen, an ex-member, explains her situation:

Nothing was ever done drastically. That’s how Jim Jones got away with so much. You slowly gave up things and slowly had to put up with more, but it was always done very gradually. It was amazing, because you would sit up sometimes and say, wow, I really have given up a lot. I really am putting up with a lot. But he did it so slowly that you figured, I’ve made it this far, what the hell is the difference? (Myers 2004, 164).

This illustrates the foot-in-the-door phenomenon. Had the members been confronted with the last and most drastic demand when they were being recruited to the church, there is a big chance that most of the people would have dropped out never to come back.

Milgram utilized the same method in his famous obedience experiment, where the demands slowly increased over time. The participants of this experiment were not immediately required to punish the “learner” with the most painful shock available. Instead they were asked to start with mild shocks, and gradually escalated the voltage as the “learner” continued to make errors (Forsyth, 2006). You can draw parallels between this experiment and the situation Grace Stoen describes: after you first start a particular behavior, it can be hard to stop. Cialdini and Goldstein (2004) argue that this can be explained by the explicit human desire to improve our own perception of self by acting according to our statements, beliefs and demands. According to these theorists, consistency is something people strive to attain, and it is exactly what the foot-in-the-door phenomenon illustrates. By accepting a minor demand, the person incorporates certain features that depict his or her recent actions, and it is this change of self-concept that makes us more susceptible to further demands (Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). One can also speculate that if the members who gave money suddenly stopped doing so, they could have been faced with the feeling that they should have stopped doing it earlier. To avoid this uncomfortable feeling of dissonance, it may have been more comfortable to keep on giving their assets away, and at the same time telling oneself that you have been doing the right thing all along.

White Nights in the jungle

The final demand put forth by Jones was the request that his followers end their lives, and a surprising number of people consented to his request. One explanation can be the power that behavioral commitment has on us. The order to take their lives as a group in the name of revolutionary suicide did not come as a surprise for the people of Jonestown. Jones mentioned death innumerable times in his speeches, and mass suicide had been a recurring theme before the movement reallocated to Guyana (Hall, 1987). On several occasions, Jones told his congregation that their wine had been poisoned, and that everyone that had drunk this wine would die within an hour. He planted conspirators among the public during their meetings who simulated spasms, then seemingly dropped dead. After a certain amount of these rather morbid repetitions, the concept of death and suicide became trivial and accepted among the group, even while it was located in California. Suicide would become even more central in the interaction between Jones and his assembly in Jonestown. White Nights was a term introduced by Jones, and was meant to describe a community in deep crisis and despair. It was not until they reached Jonestown that the members became closely familiar with this term, as well as the fact that the outcome of a White Night could be mass death. During such events, the inhabitants of Jonestown were awakened by sirens and guards that walked from house to house to insure that every person heard and acknowledged the call and gathered in the pavilion. On the most extreme cases of these White Nights, which of there were reportedly to or three in Jonestown’s history, the inhabitants armed themselves in anticipation of an attack from the armed forces of Guyana, mercenaries and hostile family members who Jones had said would attack them. The more moderate White Nights occurred more often, according to survivors, numbering a dozen or more while Jonestown was active. These White Nights were defined by the members’ own testimonials that largely were defined by their own commitment to the Cause, combined with their willingness to die for their common goal. Deborah Layton Blakey lived in Jonestown for several months before leaving in the spring of 1978. She spoke to numerous officials in the American government in hopes that it would take action in Jonestown, a place she felt was experiencing a very unhealthy development. Blakey described the suicide preparations during the White Nights:

We were informed that our situation had become hopeless and that the only course of action open to us was a mass-suicide for the glory of socialism. We were told that we would be tortured by mercenaries – were we taken alive. Everyone, including the children was told to line up. As we passed through the lines, we were given a small glass of red liquid to drink. We were told that the liquid contained poison and that we would die within 45 minutes. We all did as we were told. (Ulman & Abse 1983, 653).

Jones managed to give rise to horror on several occasions within Jonestown by telling the occupants that their group had fallen victim to a conspiracy, and that all people who did not belong to the Peoples Temple were enemies who could not be trusted (Ulman and Abse, 1983). This apparent antagonizing of the out-group may have strengthened the unity in Jonestown, as well as emphasizing Jones’ role as a protective leader and father figure within the in-group. Among other things, Jones said that the black members of the Temple would be incarcerated in concentration camps and that whites would be victims of a CIA-operation during which they would be hunted, tortured and killed, if they did not follow his demands (Ulman and Abse, 1983). Misplaced anger and frustration among the people in Jonestown derived from the conditions they lived under, and could have led to group paranoia where the members in a large degree overestimated the provocations that came from the outside-world, which in turn caused severe fear and concern regarding what threat the out-groups really could impose on them. The fear of these out-groups, which consisted of Concerned Relatives, the media and the U.S. government, seems to have strengthened the feelings of isolation and alienation among the people in Jonestown, which in turn acted as contributing factors to the mass-suicide. Drinking the poison was seen as the ultimate loyalty test towards Jones and their common goal; the White Nights functioned to build up a form of behavioral commitment that increased the chances of repeating this behavior at a later stage, should it be necessary to do so. In other words, the very last White Night was mainly a repetition of previous practiced behavior. It seems unlikely that the members drank the poison on the night of the suicides because they thought it was only a drill. Jones had already stated the congressman was going to die, and then later that Ryan had been shot. This contributed to a more serious situation than they were used to from previous White Nights. In addition, on previous White Nights, the cooks were dismissed so they could prepare a collective meal that was to be enjoyed after the White Night had passed. On this night however, they were present. In addition to these novel factors, people had already started to die when others stood in line in front of the vats, and on the tape that has been used in this essay, one can hear people crying in despair. The question of why these people still decided to drink the lethal cocktail can be illustrated by theories of conformity.

Conformity – why did not more people defect?

In Milgram’s classic experiment on conformity and obedience, the results showed that only 10 % of the participants were obedient to the very end when two “team mates” that were planted by Milgram refused to continue with the experiment (Forsyth, 2006). The same phenomenon was observed in Asch’s experiment: a participant’s conformity was reduced when this person received an “ally” who did not join in on the majority’s decision (Asch, 1951). Although Jonestown developed into a place where the fear of punishment and humiliation became more and more apparent. It was also shown by Milgram’s and Asch’s experiments that obedience was not necessarily the result of threats of violence and repercussions. The essay will now venture into what methods were used in Jonestown to maintain the conformity and passiveness among the members.

Jeannie Mills belonged to the inner circle of the Temple before she decided to leave after six years membership. She described the conditions concerning Jones and his inability to accept towards criticism like this: “There was an unwritten law but perfectly understood law in the church that was very important: ‘No one is to criticize Father, his wife, or his children’” (Osherow, 1995, no page available). Thus, criticism and individual thinking concerning the running of the church and its leader was not encouraged, and Jones was the unmistakable leader who was to be obeyed without question. In addition to this, Jones worked fiercely to root out potential rebels. He planted members he trusted among the people of Jonestown, and these were asked to report back to Jones if they came across any form of criticism or doubt expressed by the members, including by their own family. Rebels and members who violated the church’s rules would risk becoming victims of public humiliation during so-called catharsis gatherings. During these gatherings, the congregation was involved in deciding the proper punishment, and the punishment could consist of physical chastisement and homosexual humiliation. Jones himself participated in executing these punishments where he sometimes administrated a severe spanking to the person found guilty of breaking rules. There have also been reports of the accused being forced into a boxing match against a stronger member – or even more humiliating, against a much weaker opponent, like an elderly lady, and being told not to defend oneself – while the audience cheered them on. In one tape transcript, we read about a mother whose teenage son had tried to run away from Jonestown, but was caught in the act and brought back. She offers to kill her son and herself for what he has done:

Male 12: I don’t think his mother shoulda did it. We should allow someone else to do it, (unintelligible word) create that hardship upon her.

Jones: Roger. I agree. I agree with that. I agree with that.

Mother: I don’t agree with it. I feel like I should be allowed to do it, and then kill myself. The church wouldn’t get in any trouble. It would be a killing and a suicide by an upset mother that doesn’t like what her son’s doing. I’ve thought about it–

Jones: That’s very honorable, but we wouldn’t dream of sacrificing you for this vermin (Q 933).

These reactions can be hard to explain, but it would seem that family members were quick to punish their own, maybe in the hopes of distancing themselves from the rebellious behavior and to prove their loyalty to Jones despite their family member’s wrongdoings. The mother’s wish to protect the church seems sincere. Jones’ earlier statements that the structure of the family itself was a part of the enemy’s system may also have led to family members stepping up to punish their own during public humiliation gatherings. Jones also had the habit of letting children be raised by people that were not of their own family, because he was of the opinion that the family posed a threat to the total devotion that was required to promote the Cause. We can assume that this in turn led to split bonds and a lack of solidarity among family members, which in turn made it hard to gain the support needed to leave Jonestown.

There were other, more practical considerations. Jones kept the members’ passports under his watch. We can imagine that having to ask your leader for your passport in a place where the ideal was not to voice any wishes of leaving, would have been a tough thing to do, even for the people with a strong desire to go home, and that this would further complicate the process of leaving the group. In addition, many of the members had given most of their possessions and assets to the church, which may have led some people to feel that they had nothing to return to in the US, even if they did make it out of Jonestown. Finally, would-be defectors were aware that they would be the subject of intense hate in Jones’ speeches if they threatened to leave, and worse, the community might take out its rage on their families (Osherow, 1995). The rewards of leaving the Temple may simply not have been worth the risk and the unpleasant confrontations that followed any expression of desire to leave the place.

Members who did not obey to the unwritten rules and peer pressure in Jonestown were placed in closed cabins where they were subjected to sedative drugs (Ulman and Abse, 1983). We can again look at the findings of Asch and Milgram: Jones’ strategic rooting out and humiliation of potential rebels kept the conformity in Jonestown in place. Those who had their doubts received little or no support from other members, thereby keeping their doubts from becoming strengthened. Theories of group polarization show the significant effect of having similar-minded people by your side when a conviction is to be reinforced. Studies have shown that the group’s conviction becomes fortified after similar minded group members have been allowed to talk among themselves (Forsyth, 2006). This was not an option in Jonestown; those who doubted had to doubt in silence; they were denied the reassurance and support needed to further develop their doubts. That the members were so afraid to express their views on the Temple and Jones as a leader, may have led the members to have a feeling of consensus in Jonestown that in reality was not present. The illusion of consensus within the group had become a fact.

Jones:… take our life from us, we laid it down, we got tired. We didn’t commit suicide. We committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world….. (Q042).

Conclusion

This essay has looked at the causes and preliminary situations in Jonestown before the mass suicide from a social psychological angle. Earlier research on this area has often largely focused on the pathological traits among the people in a charismatic group who decide to end their lives. This essay has taken a different approach where the main focus has been the situational influence the members of Peoples Temple experienced during their time in Jonestown. It has attempted to show the reader that these situational factors combined with Jim Jones’ strategies of power led to the Temple’s tragic end in 1978, when over 900 people died as a result of their leader’s orders of executing the idea of revolutionary suicide. The essay has further attempted to illustrate how mass suicides can happen by using social psychological theories of leadership, power, conformity and persuasion. The individual aspect has been knowingly avoided to better illustrate the importance of the social influence that played its part in the Jonestown incident. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that all the previous mentioned social psychological aspects can be found represented in the Jonestown case, since tapes made by Jim Jones further illuminates the conditions the people of Jonestown experienced 30 years ago. The tragedy that would prove to be the end of Peoples Temple and the movement’s dream of a world where all people were equal would be remembered as the most severe case of mass suicide in the modern world. Even if the media portrayed members of People Temple as easy to fool and weak individuals who fell victim to the schemes of an evil, charismatic leader, this could not have been further from the truth. The truth is that Peoples Temple consisted of a group of normal people who were products of various situational factors that would prove to be fatal in the end. The increasingly paranoid Jim Jones grew less tolerant of criticism from his own followers when they relocated to Guyana, and he convinced the group that they were being persecuted by the outside world. Isolation, threats, lack of social support and Jones’ style of leadership worked in combination to bring the movement to its knees and ultimately its end. In the morning hours of November 19 th, 1978, more than 900 people lay dead in the jungles of Guyana: blacks, whites, old, young, educated and non-educated. The truth is that under special circumstances, we can fall victim to the powerful effect that social influences can have on us; the very last White Night in Peoples Temple serve as a reminder of this.

References

Barker, E. (1986). Religious movements: Cult and anticult since Jonestown. Annual Review of Sociology (12), 329-346.

Cialdini, R. B. & Goldstein N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology (55), 591-621.

Dawson, L. L. (red.). (2003). Cults and new religious movements. A reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Forsyth D. R. (2006) Group processes. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Freedman, J. L. & Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(2), 195-202.

Hall, J. R. (1987). Gone from the promised land: Jonestown in American cultural history. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books.

Hunter, E. (1998). Adolescent attraction to cults. Adolescence, 33(131), 709-714.

Jones, E. E. & Harris, V. A. (1967). The attribution of attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 3, 1-24.

Myers, D. G. (2004). Exploring social psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Petty, R. E. & Cacioppo T. (1984). The effects of involvement on responses to argument quantity and quality: Central and peripheral routes to persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 (1), 69-81.

Osherow, N. (1995). Making sense of the nonsensical: An analysis of Jonestown. I E. Aronson (red.), Readings about the social animal (ss. 68-87). New York; W H Freeman. (This article also appears on this site.)

Raven, B. H. (1993). The bases of power: Origins and recent developments. Journal of Social Issues, 49 (4), 227-251.

Ross, L. D. (2001). Getting down to fundamentals: Lay dispositionism and the attributions of psychologists. Psychological Inquiry, 12(1). 37-40.

Ulman, R. B. & Abse, D. W. (1983). The group psychology of mass madness: Jonestown. Political Psychology, 4(4), 637-661.

Kohl, Laura Johnston. Retrieved October 11, 2006 from CNN, “Jonestown survivor: ‘Wrong from every point of view'”

Wise, David Parker. (2003). 25 Years Hiding From a Dead Man. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

Q 042: FBI Transcription. Retrieved September 15, 2006. The tape is available as audio here.

Q 49 (Part 1): Jonestown community rehearses answers for reporters. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

Q 933: Jim Jones admonishes two teenagers for attempted escape. Retrieved November 11, 2006.