(Editor’s note: This article is republished courtesy of MLive.com. The original article appears here.)

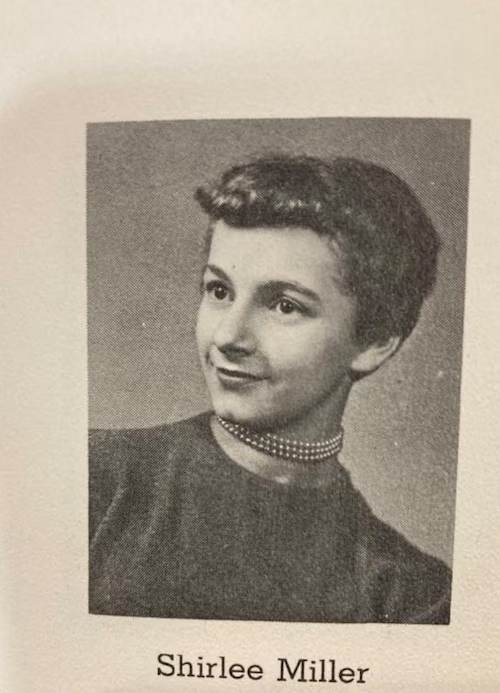

(MLive.com editor’s note: This is the first installment of a five-part series on the life of Bay City native Shirlee A. Fields (nee Miller), who was among 918 people who died in a mass murder-suicide in Jonestown and other Guyana locations on Nov. 18, 1978.)

BAY CITY, MI — Shirlee A. Miller was a daughter of Bay City. Raised in a Jewish family with her two sisters in the 1940s and ‘50s, she could often be found in her father’s drugstore. Her teachers at Farragut Elementary School occasionally took advantage of this, tasking her with bringing them her father’s wares.

At 18, Shirlee bade farewell to her hometown for the west. Settling in California, she married a man in her father’s profession and mothered two children.

But malefic clouds were on the horizon for Shirlee and her family.

Driven to eradicate poverty and injustice, Shirlee encountered a charismatic religious leader with like-minded ideals. Like Shirlee, he was a Midwesterner, born and raised in Indiana. From his pulpit, he condemned all manner of social ills — racism, sexism, and classism. At the same time, he uplifted his audience with hope for a better world, his flock reflecting the diversity he championed.

With aviator sunglasses and coiffed raven-black hair, the fiery orator cast an imposing image, amassing thousands to his cause from across the nation.

His name was the Rev. Jim Jones, his congregation the Peoples Temple. After joining the movement, Shirlee and her family followed Jones to the wilds of a South American rain forest in July 1977, arriving in a settlement amid the lush greenery — the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, better known as Jonestown.

Within a year of her arrival, Shirlee’s hope for an egalitarian paradise devolved into a heart of darkness. She and her family would die there, along with hundreds of others in the Jonestown Massacre on Nov. 18, 1978, a mass murder-suicide led by Jones.

Yet 45 years later, Shirlee’s voice echoes from documents recovered in the aftermath. In a handwritten note to Jones, she advocates for mass suicide, saying she will gladly die for the group’s cause. She suggests starvation as a method, stressing their act needed to draw heavy publicity and “be heard in all quarters of the world.”

Another sees Shirlee outline her devotion to Jones. In one audio recording made months before her death, she tells Jones the community has discovered a plant that could prolong life.

Hours after silence settled over the isolated compound on Nov. 18, 1978, Guyanese soldiers hacked their way through the foliage and uncovered a macabre scene — 909 bodies scattered in piles, some with their arms eerily wrapped around those nearby. The dying had fallen in rows so close they were stacked in layers atop one another.

All died from cyanide poisoning, aside from Jones himself and a nurse, who died from gunshot wounds. An additional four Temple members died in the Guyana capital of Georgetown, while five people, including a U.S. congressman, were shot to death by Temple members.

The day’s death toll reached 918. Before the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001, it marked the single greatest loss of American lives from a non-natural disaster.

Who was Shirlee Miller?

Shirlee Ann Miller was born Dec. 15, 1937, to Harry V. and Jeanette Miller, who lived in the 100 block of North Grant Street in Bay City. She was the couple’s second daughter, after the birth of Marilyn B. Miller in September 1933.

Her parents’ families emigrated from Russia, census records show.

The 1940 U.S. Census states the Millers lived on North Jackson Street, with her father’s occupation listed as druggist and her mother’s as clerk. Harry Miller owned Miller’s Drug Store, 905 Columbus Ave. The building still stands, with his first-born daughter’s name etched in stone above its door.

A decade later, the census shows the family back living on North Grant Street, now joined by a 9-year-old daughter, Dolores M. “Dee” Miller.

The spelling of Shirlee’s first name varies throughout her life. Her birth certificate and grave marker in Los Angeles have it as “Shirley,” while two of her high school yearbooks go with “Shirlee.” In documents recovered from Jonestown, Shirlee signed her name with the double E.

Ruth Neitzel, 86, remembers Shirlee as a close childhood friend. Born the same year, they grew up and played together in their East Side neighborhood.

“I know she was popular and just good people,” Neitzel said. “She was just an everyday normal, nice-looking girl.”

Neitzel recalls visiting Shirlee’s father’s drugstore.

“I can picture the inside of the store and everything,” she said. “Kids were very close in those days.”

Colleen Turmell, 86, attended Farragut Elementary and Central High School with Shirlee. Though they weren’t close friends, she too recalls often going to the store and attending a birthday party at Shirlee’s house.

“I know she was a nice person,” Turmell said. “She was a quiet girl and never got into any trouble, as far as I know. Her family was nice.”

Shirlee’s name comes up often in Bay City Times archives from the 1940s and ‘50s. In the summer of 1949, an 11-year-old Shirlee and her older sister attended the YWCA’s Camp Maqua on Loon Lake in Iosco County. She often attended parties hosted by her mother and was noted for her singing.

Upon turning 13 in December 1950, she was the focus of her own gala at the Wenona Hotel, where the Delta College Planetarium now stands. The following August, the newspaper notes she had returned from a 10-day trip visiting a maternal aunt in Detroit.

Shirlee attended Bay City Central High School, graduating in 1955. That fall, she began attending the University of Colorado. As a freshman, her classmates voted her a pinup girl in their magazine, “Colorado Engineer.” When her parents visited her in Denver in the fall of 1956, they took in performances of Nat King Cole and Dorothy Collins, as noted by The Bay City Times.

Shirlee later graduated from the Colorado Women’s College-Denver, where she was affiliated with the Denver Club and Tri Chi.

In July 1962, she was the maid of honor at her younger sister’s wedding in Los Angeles. By then, their parents were living in Phoenix, Arizona, having closed their drugstore in August 1956.

Shirlee, at 25, wedded Donald J. Fields on Aug. 11, 1963, at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel in California. The Sept. 8, 1963, edition of The Bay City Times reported their union.

Donald Fields, then 31, hailed from Buffalo, New York, had served in the U.S. Army and worked as a pharmacist. At various points, Shirlee worked as a pharmacist’s assistant, hospital dietitian, medical secretary, and nutritionist.

The couple had two children in California, Lori B. Fields on Dec. 6, 1965, and Mark E. Fields on March 22, 1967.

Both of Shirlee’s sisters are now deceased — Marilyn having died in Florida in 2021 and Dolores having died in California in 2013.

After high school, Turmell lost contact with Shirlee. Neither she nor Neitzel knew of their friend’s fate until this fall.

Media at the time missed the local connection to Jonestown. Bay City Times archives indicate the paper did not report on Shirlee’s death. Briefs in 1995, 2000, and 2005 even list her among Central High alumni being sought for class reunions.

Fielding M. “Mac” McGehee III, researcher and a leading authority on Jonestown, said this isn’t surprising.

“The listing of those known to have died didn’t emerge for several weeks, and only with the assistance of surviving Temple members in the U.S.,” said McGehee of the Washington state-based Jonestown Institute, a project of Special Collections of San Diego State University.

McGehee and wife Rebecca Moore operate the institute’s comprehensive website, Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, a treasure trove of documents, first-hand accounts, investigative reports, and remembrances. Two of Moore’s sisters joined Peoples Temple and died at Jonestown, as did her 3-year-old nephew, fathered by Jones.

“Even the earliest identifications — including my sisters-in-law — weren’t known until late November/early December, and we knew they had been down there,” McGehee said.

Three decades after the massacre, McGehee in 2008 was the first person to compile a list of all 918 people who died that day.

Authorities identified Shirlee and her husband’s body, initially designated as G-54 and G-55, by their fingerprints. The designations suggest the bodies weren’t identified until late in the process, McGehee said.

Learning her childhood friend died in the infamous massacre left Neitzel reeling.

“I am absolutely shocked she would get involved in something like that,” she said. “It’s hard to believe. She came from very good family, a very strong family. How do you explain something like that? I still have a hard time thinking, ‘How did that happen to her?’”

Shirlee’s story is one of nearly a thousand McGehee has chronicled.

“Everyone has a different story of how they ended up (in Jonestown), especially as the population was as diverse as it was,” he said.

Through the wealth of sources McGehee and Moore have curated and made available on their website, one can get a picture of how the Fields family they spent their time in Jonestown.

“They were an important family,” McGehee said. “(Shirlee) does show up in a lot of different places.”

(Cole Waterman is a Michigan-based crime reporter with a long-held interest in Peoples Temple and Jonestown who has submitted numerous primary source transcripts from the FBI’s FOIA files to the site beginning in the fall of 2023. He can be reached at Cole_Waterman@mlive.com.)