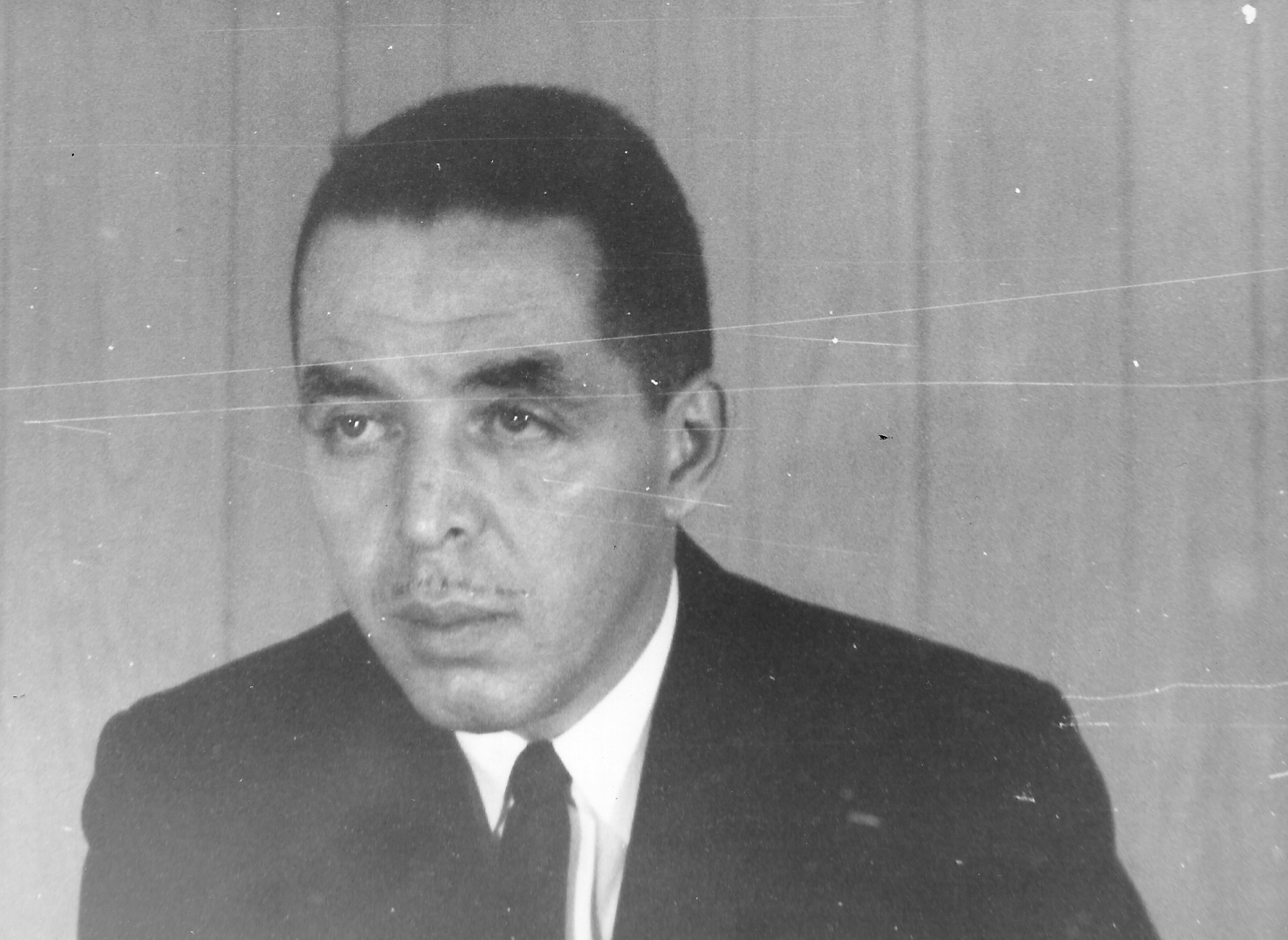

In the tumultuous landscape of 1960s America, Reverend Albert Cleage, Jr. emerged as a forceful advocate for black self-determination and religious transformation. As the founder of the Shrine of the Black Madonna in Detroit, Cleage became the visionary behind Black Christian Nationalism, a movement that sought to fuse Afrocentric theology with radical political action. He called for black people to establish their own institutions as a means to secure both psychological liberation and material well-being. His message resonated far beyond Detroit, placing him at the forefront of black nationalist discourse during the late 1960s.

Cleage’s Black Christian Nationalist movement was a revolutionary project aimed at reshaping black political and cultural life. For nearly thirty years, he led groups of dedicated Pan-Africanists who established Shrines across the country, three of which remain today in Detroit, Atlanta, and Houston. (His first planned satellite Shrine outside Michigan was Rabbi David Hill’s House of Israel in Cleveland; Hill was a figure whose strange and violent career in Guyana—and tangential link to Jonestown—has been explored by Nishani Frazier for this website.) Cleage envisioned Black Christian Nationalists as a prophetic vanguard; his apocalyptic rhetoric, which hinted at a coming “Pan-African revolt,” reflected his belief that true justice would only be achieved when black people could build their own parallel institutions, free from white domination.

Although Cleage and Jim Jones are rarely discussed together, their movements shared common threads, both in their critique of racial injustice and their vision of creating new social orders. While researching for my book, The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America, I uncovered unexpected ties between Cleage’s Black Christian Nationalist movement and Peoples Temple.

For a time in the late 1960s, Cleage was the best-known black nationalist pastor in the U.S., advocating for a radical reimagining of Christianity. He believed that black people should destroy inherited religious symbols—starting with depictions of a white Christ and Virgin Mary—and replace them with images that reflected their own identity. Although his views placed him on the fringes of mainstream black religious thought, Cleage left an indelible mark on the twentieth century’s black freedom movements, and on Jim Jones himself.

***

In the 1970s, new religious movements—Black Christian Nationalism among them—were emerging in response to the many ways American society appeared to be failing its people. There was a thin line separating pragmatism from extremism. What some called spiritual havens, others decried as toxic cults. As I learned more about Black Christian Nationalism, becoming increasingly aware of the way its tenets challenged many of the bourgeois values that had defined my own childhood in and outside of Detroit, I began to see that the question of whether it ever constituted a “cult” would be the most sensitive one to raise. It is also one of the hardest to answer.

When I first asked my mother’s parents what they knew of the Shrine of the Black Madonna, their mouths twisted. Ours was not a family of black nationalists. My grandfather James was formed in the mold of his mother’s much more famous church in Chicago. She had attended Mt. Olivet Baptist in the 1950s, during the halcyon days of Reverend Joseph Harris Jackson, one of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s most vocal black opponents and, later, a critic of liberation theology. Mt. Olivet was a church in the Booker T. Washington fashion—espousing thrift, racial uplift, self-improvement, and harmony within the bounds of the existing social order. Even as a child, I sensed that there was not much tolerance in my family for deviation from the norms of respectability. Albert Cleage, Jr., was, in my grandparents’ eyes, the leader of a cult.

Within the broader history of black utopian movements, the word cult has a particular relationship to the notion of social power. In Black Gods of the Metropolis (1944), the anthropologist Arthur Huff Fauset wrote of “black cults” such as the Nation of Islam, the Black Jews, and the Peace Mission Movement of Father Divine. Fauset was sympathetic to black movements that had no desire to be understood by outsiders. His study of the new black religious movements of the pre-WWII era inspired the later work of one of the leading black religious historians of the 1960s and ’70s, Joseph R. Washington, Jr. In his own book, Black Sects and Cults (1972), Washington defined cults as “islands of moral unity” and “variations of the search for power.” These moral islands arose in rejection of an establishment institution or ideology. For those who inhabited these islands, it was better to be free and misunderstood than to be a debased slave. In the black cult, Washington wrote, “it is understood that the enemies of black people will be defeated, that black people will live in joyful abundance in a new world of their own creation.

***

On her wedding day in May 1969, Jewell Eralene Worley, a seventeen-year-old student, was one of three white brides standing at the altar of her church in Ukiah, a rural settlement in northern California. Each bride wore a long-sleeved dress of white satin and a veil that hung at her elbows. They were distinguished by the colors of their dress bows, which matched their carnation ribbons, the dresses of their attendants, and the frosting on their cakes. Jewell’s color was blue. Her pastor’s wife, Marceline, sang a solo over organ music, a Sondheim song about finding peace and quiet in some unknown place.

One month later, Jewell wrote a short letter to Albert Cleage, Jr. at the prompting of her pastor: “Dear Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr., I’m writting [writing] just to let you know that I think it’s wonderful what you are doing for your people. I just want to praise you for the strong stand and the pride you have for your people. I’m a member of People’s Temple pastor [sic] by Jim Jones. Although my pastor is white he has adoped [adopted] black children and many other races. I was wondering if you would send me a picture of your black christ for my chruch [church]?”

Another member of Peoples Temple, Jodi Jow, explained in her own letter to Cleage why he might find a like-minded spirit in her pastor. “[Pastor Jones] bases his teachings and his life on the practice of racial equality and love,” she wrote. “We live in a predominantly white town, but nearly all of the black people here belong to our church and we pride ourselves on this fact. We hope to have more joining our congregation . . .”

Jewell and Jodi both requested duplicates of the artist Jon Onye Lockard’s Black Messiah painting, which hung in the Shrine’s lobby. From California’s Redwood Valley, Jim Jones was, like Cleage, becoming popular for criticizing the social norms of American society and hypocrisy within mainstream Christianity. Since the 1950s, Jones, a white man, had been styling himself as a holy seer and faith healer in the mold of black religious leaders such as Father Divine and Sweet Daddy Grace. Jones was on the cusp of opening another branch of the Peoples Temple in San Francisco’s Fillmore district, where Cleage once lived as black wartime workers came to the area in the early 1940s. After Cleage left San Francisco, black migration to the district continued for the next thirty years and peaked in the 1970s. By then, the Peoples Temple was at the height of its influence, commended by the local press and composed mostly of black members.

As early as 1969, Jones was starting to conflate blackness—the social status that he said society feared most—and godhood. “Black is a consciousness,” he said during a service in 1973. “Black is a disposition. To act against evil. To do good.” Jones’s messages around this time were as reminiscent of Howard Thurman as of Father Divine. He insisted on equality between people by denying that race existed. He profaned race by profaning blackness, calling himself a “nigger,” seeing his own face reflected in Cleage’s invocations of the Black Messiah, and listening to his wife, Marceline, singing “Black Baby” for the Peoples Temple Choir—a promise that racial prejudice would one day leave the hearts of men.

Some of the bad press the Peoples Temple started to receive in the early 1970s spilled over to the Shrine. In October 1972, a month after the journalist Lester Kinsolving became one of the first people to expose abusive practices at the Peoples Temple in a series of articles for the San Francisco Examiner, he dismissed the Black Christian Nationalists as “Cleage’s Black Jesus cult.” He called Cleage himself, erroneously, a “white-hating minister.” Kinsolving’s conflation of Cleage and Jim Jones’s efforts “to create a Utopian community along the lines of the early Christian church” was the kind of rhetoric that pushed the Shrine to the edges of a movement it still had every intention of helping lead: that of building enduring black nations within the nation.

Six years after Kinsolving’s remarks, in 1978, Jim Jones ordered the deaths of hundreds of his followers on the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project compound in rural Guyana. More than nine hundred people died by murder or forced suicide, including Jones himself. Patty Parks and Judy Ijames, two of the other women from the Peoples Temple who had written letters to Cleage in 1969, died in Jonestown as well. The massacre reinforced the fear that groups which sought to separate themselves from mainstream society, no matter their stated goals, were likely to bend toward fanaticism and abuse. The hope that one man might truly be a prophet became the expectation that he was probably a crank.

***

On the surface, the resonances between Jones and Cleage were profound. Both men were fluent in the evolving languages of black revolution. Each led militant social action churches that spanned the periods of civil rights and black nationalist agitation. Their churches provided social services—access to rehab programs and medical support, child and elder care, communal living arrangements—that were missing from most other churches around them. But though Cleage believed in the possibility of some kind of black apocalypse—a slow, mass death brought on by crises of joblessness and despair—Jones was sure that doomsday was inevitable and near. He feared the dropping of atomic bombs or ambushes by armed government forces. Unlike Jones, Cleage’s response to the ruin he saw in black communities was to refuse the death wish. He wanted to send self-sufficient apostles into the world, where they knew some great change was afoot even if they could not name the hour.

Though it did not always succeed, the purpose of Cleage’s ministry was to diffuse power rather than consolidate it in himself. He was one black man among many people, he assured his followers in the church, and he was vulnerable to the same diseases of the soul. Cleage had issued a warning in 1967 against “personality cults,” writing that an organization “has to be more than a group of people who are attached to a personality and are ready to follow him.” Still, he would never entirely escape the contradictions of his stated goals and his position as the patriarch of a Christian church that had its own strictly enforced hierarchies.

It is true that Cleage was sometimes skeptical of gifts from Shrine members and expenditures on his behalf. Offering him a new watch when he had one that worked fine made as much sense to him as printing his face on a T-shirt, a gesture that once infuriated him. It didn’t seem that he wanted to be treated like an indispensable savior, but a minority of Black Christian Nationalists nevertheless referred to him as “my father,” the “Master Teacher,” or the Black Messiah himself.

The notion that a prophet or an elect group possesses special insight into the nature of good and evil has always been an ingredient of and impediment to certain visions of utopia. Since the late 1960s, Cleage had been telling the members of his church that they were “God’s chosen people,” like the persecuted Israelites, who would never be fully cowed by their oppressors. With this declaration, Cleage intended to instill a sense of purpose in those who would listen. In theory, he was working toward his own obsolescence. He wanted to ensure his movement outlived him, and that when he died, Black Christian Nationalists would continue their fight for dignity and their search for a lasting Promised Land.

Cleage gave himself the great challenge of guiding a spiritual nation through the dark, away from an illuminated horizon that only seemed to light familiar trails. But although the Black Christian Nationalist movement was unusually egalitarian in many ways—with its emphasis on communal work and shared resources, rotating leadership roles open to men and women, and semi-autonomous groups that led the Shrine’s expansion into other cities—Cleage was always at the reins. His approach to leadership was fatefully entwined with the patriarchal nature of the Christian church. Like many utopian prophets, Cleage did not expect he would live to see his most dire predictions borne out or his most beautiful dreams come to full fruition. He felt it necessary, all the same, to lead his people until he could do it no more.

(This article is adapted from The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024)

(Aaron Robertson is a writer, an editor, and a translator of Italian literature. His translation of Igiaba Scego’s Beyond Babylon was short-listed for the 2020 PEN Translation Prize and the National Translation Award, and in 2021 he received a National Endowment for the Arts grant. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Nation, Foreign Policy, n+1, The Point, and Literary Hub, among other publications. He may be reached through his website .)