On March 1, 2024, I released the album We’re Able (Forty Dialogic Valences). I will say up front that this project would not have been possible without incredible help from (1) the manager and editor of this site, (2) the former Temple members/survivors of both Peoples Temple and the November 18, 1978 tragedy at Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, who I’ve spoken with over the years, and (3) those adjacent to the Temple – authors, artists, activists, media creators – who provided me with much needed context.

On March 1, 2024, I released the album We’re Able (Forty Dialogic Valences). I will say up front that this project would not have been possible without incredible help from (1) the manager and editor of this site, (2) the former Temple members/survivors of both Peoples Temple and the November 18, 1978 tragedy at Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, who I’ve spoken with over the years, and (3) those adjacent to the Temple – authors, artists, activists, media creators – who provided me with much needed context.

*****

We’re Able (Forty Dialogic Valences) sort of took me by surprise. While I have no idea how it comes across to people, for me, it’s deeply emotional music.

What follows is the story of how this music came into existence.

Despite very much loving individuals and very much valuing community, I feel somewhat, like, non-standardly about the idea of community. The idea of community – and being a part of a community – is never not-fraught for me. While I’m stating this very simply, my actual thoughts about it are super complicated/twisty-turny.

The previous draft of this essay, which was closing in on 20,000 words, took 3,700 words to outline my feelings about community in a somewhat detailed way. As you can probably imagine, it was all very, very boring.

So, here’s my attempt at collapsing 3,700 words into a single sentence:

While community is unambiguously important for all of the reasons we all think it’s important – and, for some people, it’s literally the difference between surviving and not-surviving – community is also a thing that causes humans to (1) transgress many of their own personally-held, personally-stated values and (2) dehumanize/other each other.

My reflexive inclination is to start qualifying that sentence and explain just how complicated I think the idea of community actually is, but, you know – apparently, that would take, at minimum, an additional 3600 words.

As you perhaps know from being a human yourself, humans can be very precious about the ways we talk about the idea of community, so, over the years, when this sort of thing has casually come up in conversation, my feelings have not been super well-received – to the point that I’ve mostly just stopped talking about this stuff with people.

Conversationally speaking, it also doesn’t help that, despite being able to very precisely articulate many of the problems I perceive, I have, like, zero practical ideas on or prescriptions for how to solve any of them.

We’re Able (Forty Dialogic Valences) bubbled up as a sort of catalog of conversational feelings around this issue. Each piece in the suite attempts to capture a mood/emotion/feeling that represents what it has historically felt like for me to be in conversations about how, when, and why people/individuals/communities dehumanize each other.

Sometimes when I ponder these pieces, I imagine myself being in these conversations, and sometimes I imagine that I’m simply observing these conversations. For the conversations I feel like I’m a part of, sometimes I’m the person making super awesome, extra-insightful points, and sometimes I’m the person who’s doing the misunderstanding, lacking context and/or unable to see things clearly.

The background to all of this is that, as a young-ish teenager, I started to become interested in why and how we all believe things, how group dynamics cause us to make certain decisions, and how we, as a species, can so effortlessly dehumanize/other each other. Over the past thirty years or so, I’ve taken some deep-ish dives into the beliefs, behaviors, and demands of different groups/communities in an effort to figure out how all of these factors conspire to create, inspire, and dictate a given individual’s personal emotional disposition and how that individual stands in relation to their community/communities.

Given that history, it’s probably not surprising that Peoples Temple has been on my radar for many, many years.

Just, as a disclaimer here: This is not a scholarly essay about Peoples Temple. This is an essay about my feelings and motivations regarding a piece of music I created. I am not a historian or an academic. I am nearly certain that I’m misunderstanding many things or not in possession of key facts. Despite maybe cataloging some things that were told to me in conversation, I am absolutely not speaking on behalf of anyone or representing anyone’s views apart from my own.

That said, at this moment in my life, I think a lot about the Temple.

- I’ve watched many, many films on the group

- I’ve read many, many books on the group

- I’ve explored art pieces made about the group

- I’ve listened to many, many podcasts about the group

- I’ve talked with some of the authors who wrote the books

- I’ve talked with some of the artists who made the art

- I’ve talked with some of the podcasters who make the podcasts

- I’ve spoken with survivors of the tragedy

- I’ve spoken with members who were a part of the group, but who left before the move to Guyana

- I’ve spoken with people who were not in the Temple, but were adjacent to or worked with the Temple in San Francisco in the 1970s

- I’ve listened to hundreds of hours of audio of Jim Jones and the Temple as they made their way from Indiana to California and, ultimately, Guyana

- I’ve spent many, many hours online on this website reading remembrances by former members, contextualizations of audio, scholarship of actual academics, and reviews of many of the films, books, and podcasts I’ve consumed in an attempt to gain even more context.

- I’ve spoken with very public people who occupy roles in our society that I suspect are, like, psychically similar to those of Peoples Temple members, in an effort to see how their experience may or may not scale with that of Temple members

Apart from fixing two small typos, here are direct quotations from three different emails I sent to former members, outlining some of the things I was looking to learn:

- “I’m writing to you because I’m wondering if you might be available to have a brief conversation with me about what it’s like to be a person in the world who literally has all of the facts/answers [that can be known] about a paradigm-shifting, archetypal, punctuating event in world history, but who is sort of forced to live in a society that would prefer to not know those facts or to pretend that the facts are all very simple/easily ignorable.”

- “Essentially, I’m a composer living and working in Boston, MA who, for the past couple of years, has been working on a piece of personal music inspired by (1) the Temple (what it was actually like vs. society’s conception of what it was like) and (2) the seemingly intractable problem of even the most well-meaning, engaged, justice-seeking humans living in our current moment sort of reflexively dehumanizing people they disagree with or don’t understand.”

- “My interest in speaking with former members has had more to do with what it’s like to be a socially-conscious, engaged, intelligent, discerning, empathetic, connected person who, through some sort of, like, societal sorcery, winds up being viewed/labeled by the rest of the world as a mindless, will-less, potentially brainwashed, enthusiastically-suicidal automaton – and what it feels like to be required by the rest of us to inhabit that sort of role.”

All in all, my concern with the degree to which we’re all dehumanizing each other led me to attempt to find the people who are most dehumanized. Right off the bat, that’s a pretty complex thing to do because humans dehumanize each other in a number of different ways.

For example, here are three ways – out of a jillion different ways – we dehumanize each other:

- Some groups, we dehumanize by treating them as if they’re violent animals, too feral to be invited into any kind of complex conversation – even conversations about their own well-being

- Some groups, we dehumanize by treating them as if they’re actual, like, unnatural, magic-wielding conjurers, using the blood of children in their fantastical, world-steering rituals

- Some groups, we dehumanize by telling ourselves that the members are will-less, group-thinking automatons who are too simple to make their own decisions about, really, any aspect of their own lives – to the point that they downright crave being led by other, more confident, [what I’ll call] “en-willed” people

Sometimes, of course, we mix and match dehumanization styles.

As for me, I was most interested in dehumanization-style number 3.

I tried to think about who our society perceives as the most will-less people alive, and it occurred to me that, quite possibly, those people are members of Peoples Temple – the people who, we tell ourselves, “drank the punch” merely upon being told to by their leader. They’re the go-to community we invoke to communicate the idea that an individual is, like, devoid of a personal, subjective experience of themself, has no personal values or intentions for themself or the world, and blindly behaves in whatever ways their leader prescribes.

I actually began working on some piece of music related to the Temple long before reaching out to the Jonestown Institute. The original concept for my piece found me organizing, analyzing, and notating clips of Jim Jones’ glossolalia (a holdover from his childhood/early-adulthood Pentecostal training/fascinations), writing the figures into more complex musical statements, and arranging the statements in some sort of formalistic way.

After working that way for a while, I wondered if I was doing the world a disservice by focusing so heavily on Jim Jones instead of the experiences of Temple members. Not being totally sure how to think about it all, I decided to put things on hold until I could talk to actual experts and gain a deeper understanding.

I started the next branch of my journey by reaching out to the Jonestown Institute and began what has now become a years-long conversation, which has helped me in ways that simply cannot be calculated.

They put me in contact with former members, vouched for me when a potential connection required vouching, clarified things for me when things needed clarifying, and complicated things for me when things needed complicating. They not only constantly left space open for my interpretation, but, at times, they just short of insisted upon me having my own interpretation. These people are, truly, looking for alternative considerations of the very, very complex story of Peoples Temple.

I was lucky to get to speak with many incredibly thoughtful former Temple members, get their perspectives on the group, hear recollections of their personal dispositions at the time, listen to their thoughts on what happened, why it happened, and what it all means to them, learn how they disagree with other former Temple members, and, all in all, just gain as much perspective as I could.

One thing that’s, like, thematically interesting to me about the way this music came together is that, from the very beginning, I unambiguously, super stridently intended for the suite to be performed on a classical (nylon-string) guitar. I don’t have much call these days to pull out my very special, concert-level classical guitar; it seemed like the exact perfect tool for this project. Having not played it for years up until the moment I took it out of its case to start practicing the pieces pre-recording, its geometry had shifted somewhat and was nearly unplayable for my particular hands. No biggie – I took a drive out to Western Massachusetts so the person who built it could make some adjustments. They made the adjustments, I took it back home, and started recording. The music was sounding nearly precisely how I hoped it would sound, which rarely happens.

Here’s what “Valence 1” sounded like on my special instrument:

The thing was, the instrument was still hurting my hands to play. Nevertheless, I kept recording. I wound up recording the first twenty-three valences with that guitar before deciding that my hands couldn’t take it. During this period, in an effort to figure this all out, I had multiple professional classical guitar players play the guitar and give me their report. It would appear that the guitar is totally within tolerances for most people but, for some reason, at some point, the guitar and I just sort of grew apart. Weird, but okay.

Letting go of using that guitar on this project was pretty rough, but, I mean, I did it because I’m a grown-up. That’s when I thought to myself, “Hey, you know how you have that inexpensive classical guitar that you love, which just hangs out on a stand next to your desk, and that you play nearly every day and use on nearly every project you record that requires a classical guitar? Maybe you can try using that thing.”

So, I did.

It sounded like this:

I hated it. It turns out that, generally, when I write a piece of music specifically to be performed on that guitar, I pointedly try to craft the composition in a way that accentuates the instrument’s strengths and de-emphasizes its shortcomings. These pieces were definite shortcoming-emphasizers. Despite having used the guitar to compose nearly all of the music on the album, I recorded two valences with it before giving up on it.

That’s when I turned to my grandfather’s classical guitar. Emotionally speaking, it’s an incredibly meaningful instrument to me, but, also, non-emotionally speaking, it’s not a super-great instrument. I spent a single day experimenting with that guitar and wound up scrapping everything.

That’s when I turned to electric guitar – so easy to play and so capable of a range of sounds and sensitivities. I tried both of my main electric guitars, but they weren’t sounding right, which is when I remembered the stereo electric guitar I have, which a friend left with me before moving to California a few years ago.

I tried it out, it worked really well, I recorded everything, and wound up with the pieces you hear on the album.

That moment is where we meet the thematically interesting thing I’m talking about.

I started off with one, single, very, very intimate, personal, and important value for myself: These pieces need to be recorded on a nylon-string guitar.

At some point, however, I somehow wound up shifting my values around until I not only felt very satisfied with an electric guitar, but I even have reasons for why it’s structurally/semantically a better choice than a nylon-string guitar.

For example, there are two separate signals coming out of a stereo guitar, which is totally representative of two people in a conversation.

The fact that the instrument belongs to a friend invokes the idea of relationships, interpersonal conversation and persuasion, love, and, at times, conversational complication.

There’s also an interesting perspective shift in that this is not my instrument and the sort of music that my body puts into it is an entirely different kind of music with entirely different considerations than the music that my friend’s body puts into the instrument.

It all just seems perfect, but, like, maybe a little too perfect, you know?

Like, I don’t think it’s exactly my-own-horn-tooting to say that, at this point in my life, I have a pretty good handle on when I’d like to use a nylon-string guitar vs. when I’d like to use an electric guitar.

It just seems fairly… convenient to me that I wound up feeling very satisfied with an end-product I started out unambiguously never wanting and I felt like it was the only option available to me, given my situation.

But also: Maybe I was really, genuinely transformed by the journey – we don’t know.

All of that said, here’s the final version of “Valence 1”.

Recording and instrument-choice aside, while I very much enjoy the way these pieces sound, for me, the emotionality of this music comes from the internal architecture of each piece.

In trying to figure out the best way to talk about some of these structural considerations in this essay, I settled on doing it through [Western] music notation.

Q: But, Joel, I can’t read music.

A: Person, I get it, but, for our purposes here, I don’t think it really matters. If you listen while you look, you should be able to, like, synesthetically get what’s happening. Like, the pictures tend to look how the music sounds. Read left-to-right. When you hear the pitches get higher or lower, the notes on the page correspondingly get higher or lower. When there are more horizontal lines connecting notes, the music’s probably going a little faster.

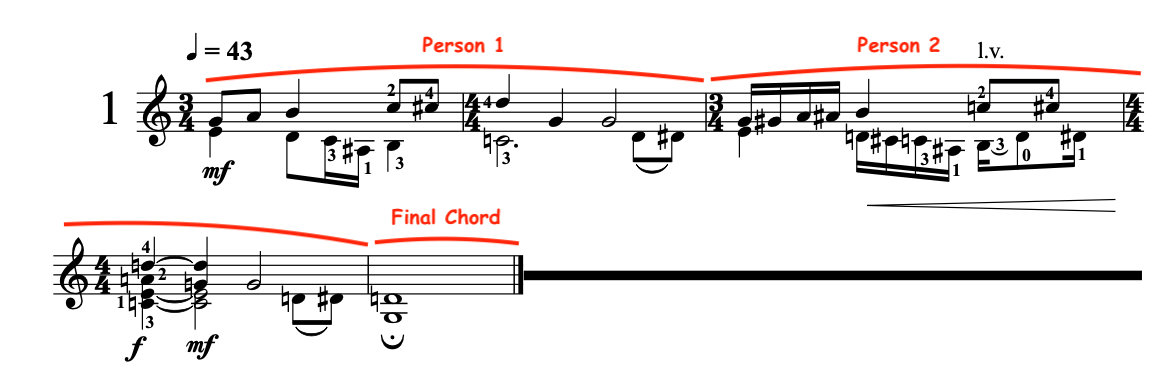

Here. Listen to “Valence 1” again while you look at this.

To me, this valence feels like a conversation wherein one person says a thing that they feel is very well-thought-out and somewhat complex, and then the other person, in an attempt to demonstrate how the first person might not be thinking about things as clearly as they could, restates the first person’s words back to them, but in a much richer, more complex way, which maybe, like, blows the first person’s mind – we don’t know. The final chord at the end is sort of open and confusing in a way that makes us unsure about where things landed.

So, first, let’s just add some lines separating the two statements (goin’ Comic Sans on this to add some degree of lightness).

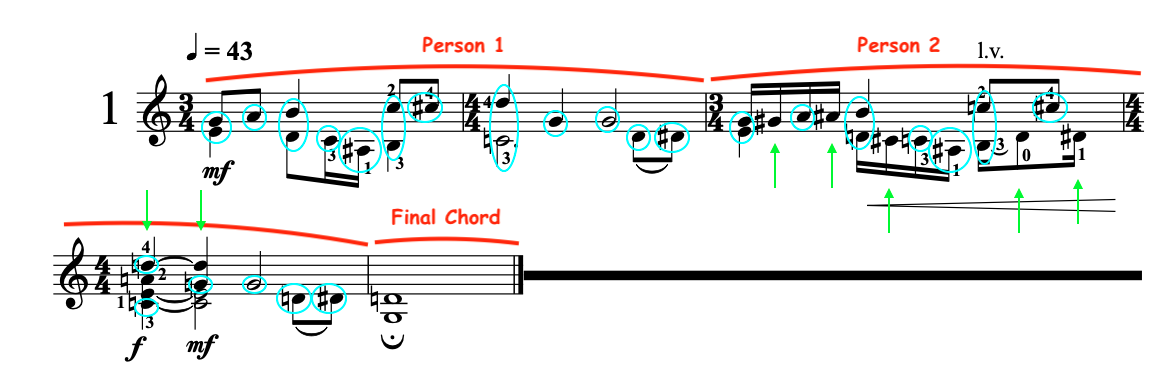

Now, let’s find Person 1’s statement inside of Person 2’s more complex presentation. The blue circles exist identically in both statements and the green arrows indicate notes that are added into the second statement to embellish it.

Now, let’s find Person 1’s statement inside of Person 2’s more complex presentation. The blue circles exist identically in both statements and the green arrows indicate notes that are added into the second statement to embellish it.

A fair number of the valences work this way: Person 1 states something and Person 2 re-states the thing back to Person 1 in an effort to show Person 1 how much more complicated things are than Person 1 thinks they are. Other valences, of course, work other ways.

A fair number of the valences work this way: Person 1 states something and Person 2 re-states the thing back to Person 1 in an effort to show Person 1 how much more complicated things are than Person 1 thinks they are. Other valences, of course, work other ways.

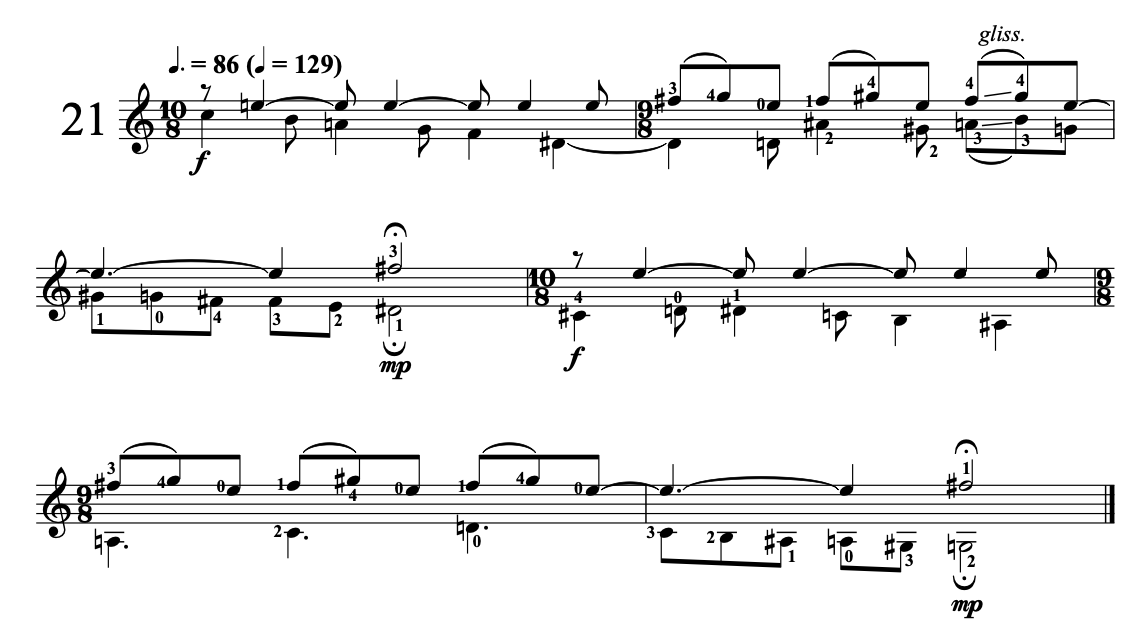

For instance, here’s “Valence 7.”

“Valence 7” also makes a statement and then embellishes the statement, but, in this case, it’s the same person doing the embellishing in an effort to make themself more clear to their fellow conversationalist.

“Valence 7” also makes a statement and then embellishes the statement, but, in this case, it’s the same person doing the embellishing in an effort to make themself more clear to their fellow conversationalist.

In “Valence 7,” Person 1 says something and Person 2 responds in a somewhat related, but disconnected way. Feeling flustered, Person 1 restates their original thought, but adds a bit more context, hoping it will get through to Person 2 more clearly. Person 2, again, responds in the same somewhat related, but disconnected way. This piece ends similarly to “Valence 1” – not entirely unsettlingly, but, like, fairly unsettlingly – this time with Person 1 feeling pretty bummed/misunderstood.

Here are the voices separated.

Here’s “Valence 7” one more time showing Person 1’s first statement (blue boxes) and then their re-statement with additional context (blue boxes plus green box).

Here’s “Valence 7” one more time showing Person 1’s first statement (blue boxes) and then their re-statement with additional context (blue boxes plus green box).

I suspect that Person 2 is actually seeing things pretty clearly in “Valence 7.” To me, Person 1 comes across as somewhat desperate to rationalize a position that they’re starting to maybe feel uncertain about.

I suspect that Person 2 is actually seeing things pretty clearly in “Valence 7.” To me, Person 1 comes across as somewhat desperate to rationalize a position that they’re starting to maybe feel uncertain about.

Other valences/conversations present the voices of Person 1 and Person 2, not as separate sections, but as two independent voices both speaking simultaneously.

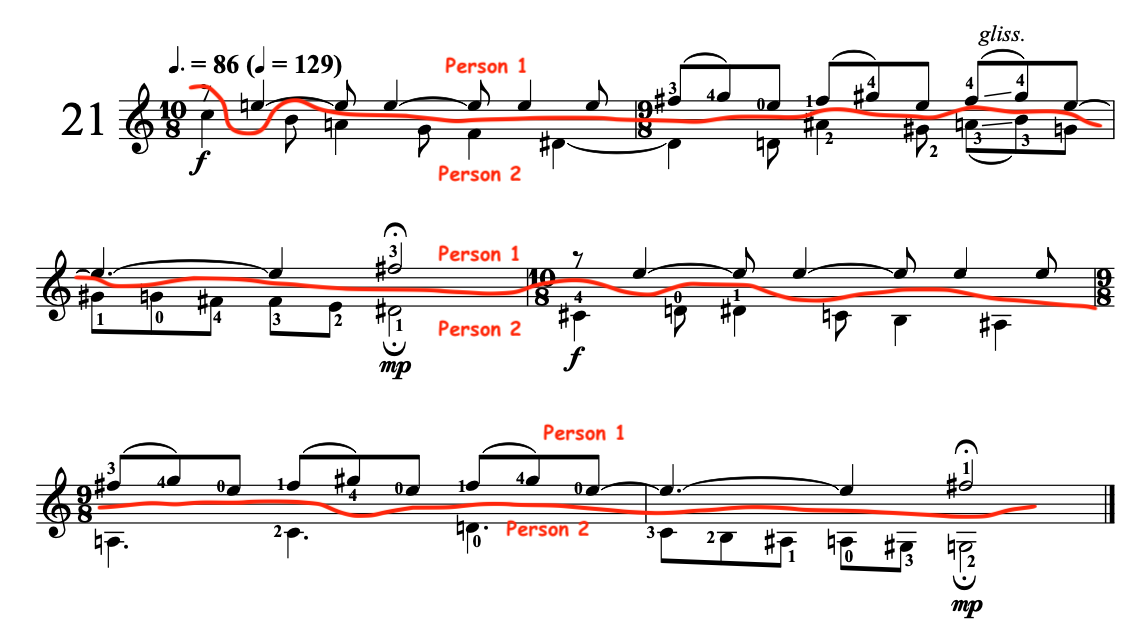

To that point, here’s “Valence 21.”

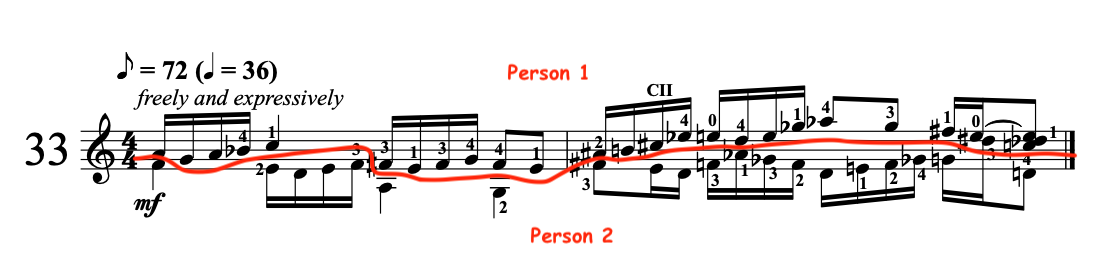

If you look at the music to “Valence 21” while listening, you’ll notice that some of the note-stems go up and some of them go down. The ones that go up are Person 1 and the ones that go down are Person 2. We can draw lines through these voices in each system and see more clearly how Person 1 is the top voice and Person 2 is the bottom voice.

If you look at the music to “Valence 21” while listening, you’ll notice that some of the note-stems go up and some of them go down. The ones that go up are Person 1 and the ones that go down are Person 2. We can draw lines through these voices in each system and see more clearly how Person 1 is the top voice and Person 2 is the bottom voice.

In addition to the two voices, there are two halves/sections of “Valence 21”’s conversation which contain very similar elements, but differ from each other in subtle ways. To me, this feels like two people attempting to break out of a conversational pattern, but not necessarily being able to do it. No one is necessarily bummed [yet] and there is a kind of resolution, but the resolution, to me, feels like it’s indicating some degree of futility.

In addition to the two voices, there are two halves/sections of “Valence 21”’s conversation which contain very similar elements, but differ from each other in subtle ways. To me, this feels like two people attempting to break out of a conversational pattern, but not necessarily being able to do it. No one is necessarily bummed [yet] and there is a kind of resolution, but the resolution, to me, feels like it’s indicating some degree of futility.

A valence which employs a similar idea – dividing the speakers into upper and lower voices – is “Valence 33.”

These voices are a bit vertically closer together than “Valence 21,” which, along with the softer performance, to me, presents a scenario that’s a bit more intimate. These two elements together – the voices being closer and the performance being a bit more restrained – gives me the feeling of two people having a conversation that actually doesn’t feel emotionally terrible to be in.

These voices are a bit vertically closer together than “Valence 21,” which, along with the softer performance, to me, presents a scenario that’s a bit more intimate. These two elements together – the voices being closer and the performance being a bit more restrained – gives me the feeling of two people having a conversation that actually doesn’t feel emotionally terrible to be in.

Here’s where we find our two interlocutors positioned.

Despite the fact that this conversation isn’t super terrible-feeling to be in, it does, to me, feel like possibly the biggest collapse in understanding of any of the pieces on the album. Like, this conversation starts out on one of the most consonant intervals available to Western-European-music-ly tuned ears and, as it moves forward, it becomes more and more discordant until finally ending on an incredibly unsettling chord. Just looking at this piece’s notation without even listening to anything, the second half of it straight-up just looks more complex and troubled than the first half. It’s almost like you can see the dialogue breaking apart on the page.

Despite the fact that this conversation isn’t super terrible-feeling to be in, it does, to me, feel like possibly the biggest collapse in understanding of any of the pieces on the album. Like, this conversation starts out on one of the most consonant intervals available to Western-European-music-ly tuned ears and, as it moves forward, it becomes more and more discordant until finally ending on an incredibly unsettling chord. Just looking at this piece’s notation without even listening to anything, the second half of it straight-up just looks more complex and troubled than the first half. It’s almost like you can see the dialogue breaking apart on the page.

Another interesting thing about “Valence 33,” to me, is that it seems like the last chord is secretly telling us that the breakdown in communication is mostly the fault of Person 1. There’s a weird, dissonant cluster in the top voice, while the bottom voice has a single, lonely pitch spoken by someone who feels like they’re just trying to do a good job, but it’s not working. :/

Lastly, I’ll talk about a valence which, to me, ties together both of the ideas I’ve discussed so far – conversational voices organized section-by-section and conversational voices organized in upper and lower voices.

People: Welcome to “Valence 37.”

Aesthetically, it’s possible that “Valence 37” is the most terrifying-/intimidating-looking of all of the valences we’ve discussed so far, but, to me, aurally and architecturally, it’s really just the best sort of set-up a human can hope for (conversational-valence-ly speaking).

Aesthetically, it’s possible that “Valence 37” is the most terrifying-/intimidating-looking of all of the valences we’ve discussed so far, but, to me, aurally and architecturally, it’s really just the best sort of set-up a human can hope for (conversational-valence-ly speaking).

The first line consists of Person 1 speaking and Person 2 responding in a way that indicates a very light, collaborative feeling and/or some sort of understanding. Armed with some small degree of conversational trust, they move to line two, wherein Person 1 is in the top voice (note-stems up) and Person 2 is in the bottom voice (note-stems down).

While neither voice in the second line, on its own, is saying anything too intense, the voices together create a deeply melancholy harmony that, at once, sounds unsettlingly out-of-place and incredibly reassuring, relaxing, and safe [to me].

While neither voice in the second line, on its own, is saying anything too intense, the voices together create a deeply melancholy harmony that, at once, sounds unsettlingly out-of-place and incredibly reassuring, relaxing, and safe [to me].

Essentially, every piece on the album contains, as its engine, some sort of underlying conversational mechanic along the lines of the pieces we’ve looked at.

There is exactly one valence on We’re Able (Forty Dialogic Valences) which is architected upon a simple rhythm from one of Jim Jones’ glossolalic incantations.

The questions I’ve been asked the most about this music so far have to do with the numbers. Specifically, why are there forty valences, how did I choose their order, and why do I speak each piece’s number before I play it?

When I started this project, I intended for the final suite to contain sixty to one hundred of these short pieces. After writing twenty-five of them or so, I started thinking, “Yikes, this is starting to feel like a lot of pieces.” At that point, I thought, “Okay, new plan,” and told myself that I’d just keep writing them until I got to a point that felt like a natural stopping place. As it happened, that stopping place was at “Valence 40.” If the feeling of resolution hadn’t come until 41 or 57 or 85, I would’ve gone with it, but it came at 40.

Sequence-wise, quite pleasingly and simply, the pieces are presented in the order in which they were written.

With regard to the spoken numbers, I included them for two reasons:

First, I knew I wanted to somehow incorporate the identity of the performer into the performance of the pieces. While our society certainly elevates individual soloists of concert-music to some degree, there is a sort of unspoken understanding that, more often than not, performers of concert-music are merely technicians, dressed in all black, whose sole job is to, like, “bring the music alive” or something. I was looking for a way to insert the human performer into the pieces and intermittently remind the listener/audience member(s) that the person performing these compositions is an actual, like, corporeal being who has internalized the compositions, interpreted them, and is presenting their very subjective understanding of them via their performance. To that end, the performance notes for the score currently indicate that the performer should look up from their instrument and clearly pronounce each number shortly before beginning a given piece.

It should go without saying that I consider my recording of these pieces – and even my above, down-and-dirty structural analysis of the pieces – to be my interpretation of them.

My hope is that other performers/individuals will bring their unique perspectives to performing these pieces, hear and see different things in the conversations than I hear and see, and find a way to communicate those things in their performance(s).

Like, maybe the cluster in the upper voice at the end of “Valence 33” is there because Person 1 is actually in possession of all of the complex, seemingly incompatible, counterintuitive facts of the matter, you know?

Secondly, these pieces are all very short and, while they sound incredibly differentiated to my ear, I just wasn’t convinced that a not-me person would be able to confidently and immediately know when a given piece started or ended. Including the numbers at the beginning of each piece solved that problem for me.

The album’s title, We’re Able, is referencing the Temple’s own 1973 album of music entitled, He’s Able. I was preliminarily a bit nervous about so overtly connecting my album to He’s Able for a few reasons. For starters, I didn’t want anyone to feel as if I was making light of or mocking the Temple in any way. Secondly, as joyful, energetic, and straight-up musically awesome as He’s Able is, there are some unambiguously problematic components to it that I certainly don’t endorse. Lastly, there’s a sort of psychic layer to He’s Able that causes it to exist in an incredibly complex space; many of the people who performed on the album lost their lives in the tragedy at Jonestown – including many of the children whose voices greet us on the album’s first track, “Welcome.” I would never want to be perceived as somehow attempting to co-opt the authenticity of these voices or feeling like my album somehow represents anything remotely as complex as He’s Able represents.

All of that said, I discussed the possibility of naming my album We’re Able with a few different people – the music director of He’s Able, former Temple members who performed on He’s Able or were a part of its production, and one other member who wasn’t associated with the album’s production, but was very helpful to talk these sorts of things through with. I asked each of these people how they felt about me titling my album We’re Able and their responses ranged from being-totally-fine-with-it to pausing and saying, “That’s what He’s Able should’ve been called in the first place,” which, of course, was a super interesting take. It’s interesting, in part, because it sort of gave me a small window into the recollecting-machine of that particular former member, but it’s also interesting because I’m not entirely sure that I mean the title, We’re Able, in a necessarily positive way. In my mind, We’re Able to harm one another as much as We’re Able to collaborate with one another.

All in all, whatever you can come up with to finish a sentence that starts with the words, “We’re able…,” is a version of how I mean the title.

The last thing I’d like to communicate here about this music, which I wasn’t expecting before I started writing it, is how much I learned about myself and my own intentions as a composer/human from analyzing it all. Looking back on the music having completed it, I think there are things I just wouldn’t’ve been able to uncover about myself without an exercise like this, and, in turn, without the insightful conversations I’ve had with all of the incredibly generous, thoughtful people I met along the way.

Being confronted with forty short, uniquely-differentiated-from-each-other pieces that came from inside of me and which were performed on the guitar – an instrument I’ve spent so much of my life attempting to understand and wield in expressively effective ways – highlighted emergent qualities in my structural-decision-making that I never realized were there and would probably never have noticed about myself and my music without having been lucky enough to have had this experience.

(Joel Roston has written music for films, commercials, podcasts, web videos, and museum installations, composed chamber works and solo pieces for numerous ensembles and instrumentalists, and performed nationally and internationally in classical, new music, and rock idioms. Joel teaches guitar, music theory, and composition privately, leads workshops on music literacy and communication for media producers, and is a visiting faculty member teaching media composition and film scoring at Longy School of Music of Bard College. https://www.joelroston.com/.)