In the almost fifty years that have passed since Jonestown, more than 80 books have been written about the tragedy of November 18, 1978, and the events that led up to it. Almost every single one of them includes mention of the abuse of amphetamines and barbiturates of Jim Jones, the leader of Peoples Temple. Likewise, some books centering on a Temple survivor include their stories of struggling with substance abuse. Independent historian Bonnie Yates has written specifically about Jones’ addiction to barbiturates along with barbiturate use in Jonestown. The present essay is, I believe, the first work dedicated to exploring addiction’s role in Peoples Temple as a whole.

Substance abuse played a significant role before, during, and after the mass deaths in Jonestown, in both the leader and members of Peoples Temple. Jim Jones abused amphetamines and barbiturates, which had a serious effect on his mental and physical state in an immediate and long-term capacity. Through its celebrated drug rehabilitation program, however, Peoples Temple helped addicts find recovery while unknowingly following a fellow addict. The deaths of 918 people not only meant the loss of what was essentially a long-term inpatient rehabilitation program, but survivors were left to recover from trauma that the rest of us can only begin to imagine.

As a child, Jones experienced conflicting views about substance use. Raised in a dry county in 1930s Indiana likely influenced a lifelong negative opinion about “drunkards.” His father, Big Jim, was probably using prescription medication to manage the painful aftermath of the World War I gas attacks that left him disabled. Later in his adulthood as the pastor of a large, racially-integrated church, Jones eventually turned to prescription medication to help him maintain the high energy church services his congregation came to love, as well as to aid him in “coming down” enough to rest (Guinn, 2017).

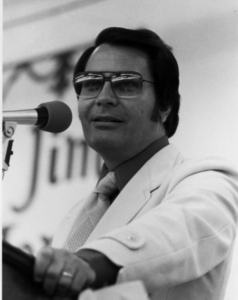

Jones’ drug use means little without considering the fact that he also demanded that Peoples Temple members submit to grueling work schedules as well as attend church services late into the night. In one recorded Jonestown meeting from April 1978, Jones asks his followers, “Why don’t you work like I do then? Why don’t you take the burdens I do then?” (Q734, 1978) Save for those closest to Jones, Temple members were largely ignorant of the drugs enhancing their leader’s performances. Associate pastor David Wise discovered dextroamphetamine – typically prescribed for narcolepsy and ADHD – in Jones’ toiletry bag in the early 1970s, years before the group’s emigration to Guyana (Scheeres, 2011). Around this same time, Jones began wearing his trademark sunglasses, claiming they would shield his followers from the holy energy that radiated from his eyes. In reality, the black sunglasses hid the telltale redness of substance use, likely amphetamines (Guinn, 2017). Interestingly, Wise, who was aware of Jones’ drug use, claimed the sunglasses also hid the fact that Jones reading from crib notes at the pulpit, which would shatter the illusion of his omnipotence (Scheeres, 2011).

Jones’ drug use means little without considering the fact that he also demanded that Peoples Temple members submit to grueling work schedules as well as attend church services late into the night. In one recorded Jonestown meeting from April 1978, Jones asks his followers, “Why don’t you work like I do then? Why don’t you take the burdens I do then?” (Q734, 1978) Save for those closest to Jones, Temple members were largely ignorant of the drugs enhancing their leader’s performances. Associate pastor David Wise discovered dextroamphetamine – typically prescribed for narcolepsy and ADHD – in Jones’ toiletry bag in the early 1970s, years before the group’s emigration to Guyana (Scheeres, 2011). Around this same time, Jones began wearing his trademark sunglasses, claiming they would shield his followers from the holy energy that radiated from his eyes. In reality, the black sunglasses hid the telltale redness of substance use, likely amphetamines (Guinn, 2017). Interestingly, Wise, who was aware of Jones’ drug use, claimed the sunglasses also hid the fact that Jones reading from crib notes at the pulpit, which would shatter the illusion of his omnipotence (Scheeres, 2011).

Despite denigrating the Christian Bible and church organizations, Jones was deified by his congregation. Through trickery, the assistance of his inner circle of advisers, and a detailed note system on many Peoples Temple members, Jones created a perception of omnipotence. His followers responded with reverence. Jones believed – and taught – that the end justified the means. He also declared that he was God. What reason would they have to suspect that their god was addicted to drugs? If they did have any suspicions, it was worth overlooking, because Jones, and through him the church members, were doing so much good for their communities. Temple members believed they served the greater good by helping their pastor.

This meant someone would have to help Jones manage his increasing tolerance to amphetamines and barbiturates. Managing Jones’ drug use meant assisting him in acquiring and administering substances, not in ensuring that he took the medication only as prescribed by a neutral medical professional. Amphetamines kept Jones’ paranoia well-fed while the church’s community service programs and political clout, which Jones believed likened him to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., brought him to the attention of state and local government agencies and to an increasingly-skeptical media. This in turn exacerbated the paranoia. Ethan Feinsod describes this paranoia loop perfectly: Jones was regularly “overreacting to a situation he had created in the first place by overreacting” (Feinsod, 1981: 128).

It was this paranoia loop that provoked Peoples Temple’s mass exodus to the dense, remote jungles of Guyana in summer 1977. Travel to the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, more commonly known as Jonestown, required an airplane or day-long boat ride followed by miles of bumpy jungle road to reach. The community’s isolation from the outside world and its efforts to create a self-sustaining utopia meant it had to establish and maintain its own infrastructure, including its medical facilities. The Jonestown clinic, nurse’s office, and small pharmacy offered medical services to community resident through its doctor Larry Schacht. For a time, Jonestown even provided medical assistance to the indigenous Amerindians living near the project.

Acquiring drugs in California could be done through Jones’ personal physician, to a degree. Jones would have Peoples Temple members acquire prescription drugs for him even through unscrupulous means, such as stealing from their workplace. Temple member Lois Ponts, for example, was reprimanded at her job for stealing drugs for Jim Jones, according to Michael Bellefountaine (2011). Addicts from the streets of San Francisco who found recovery in Peoples Temple, like Chris Lewis, may have repaid Jones (and through him, the church) for saving them from substance abuse by using their former connections to buy drugs for their pastor. Moving to the jungles of Guyana would likely present new challenges for Jones’ ever-increasing tolerance. He was convinced that various U.S. agencies such as the FBI, the FCC, Customs, and even the U.S. Postal Service were investigating him and his interracial, socialist church. His fears were entirely justified, although as any former amphetamine user could tell you, the drugs intensified those fears.

Jones likely wouldn’t risk getting his fix through Guyana’s pharmacies under his own name, though he remained in contact with his physician, Dr. Carlton Goodlett, back in California; Goodlett was aware that Jones was using amphetamines and barbiturates (Wooden, 1981). According to several former Jonestown residents, including Deborah Layton (1998), Jones had Temple members search the luggage of newly-arriving members to confiscate any medications and valuables they found. Jones may also have acquired drugs through Venezuela, as several Jonestown residents made supply runs to Guyana’s western neighbor. After Congress passed the Psychotropic Substances Act in October 1978, Jones had Joyce Parks scour Georgetown, Guyana for an additional 100 vials of injectable Valium, which was everything “she could get her hands on” (Scheeres, 2011: 176). Notably, the request does not include amphetamines.

In Jonestown, Jim Jones’ oldest son Stephan told his mother Marceline, “You’re talking about going to God and telling him he’s a drug addict” (Wright, 1993: 78). But at what point, and why, did Jones stop using amphetamines? In Jonestown’s final months, Jones lacked the trademark superhuman-like energy of amphetamine use, his fiery sermons giving way to slurred speech over the Jonestown loudspeaker system, worsening with time. Jones rarely left his cabin, and when he did – as on one occasion shortly before Congressman Leo Ryan’s visit – Odell Rhodes reported that Jones “looked like old spaghetti” (Feinsod, 1981:152).

Nevertheless, the Jonestown pharmacy records recovered from Jonestown after the tragedy and released under the Freedom of Information Act include no prescription amphetamines. While I have yet to find a primary source that names specific pharmaceuticals found in Jones’ personal cabin around November 1978, other available Jonestown inventories include Valium, Thorazine, Quaaludes, pain killers, surgery-level tranquilizers, but no amphetamines (RYMUR 89-4286-J-1; RYMUR 89-4286-J-2; RYMUR 89-4286-OO-1). Jones’ autopsy in the United States, which was compromised by embalming, found a level of pentobarbital in his system that, without a developed tolerance to the drug, “are within the toxic range, and … would have been sufficient to cause death.” It did not, however, find any amphetamines (Autopsy, James Warren Jones, 1978).

Amphetamine is highly addictive. My own experiences with the drug, both prescribed and recreational, leave me convinced that Jones did not make a willing choice to stop using it. It’s likely that Jones’ physical and mental state in late 1978 were highly affected by amphetamine withdrawal after at least six to seven years of chronic use. Additionally, I suspect that his closest aides and nurses may have tried to help him manage the detoxification and withdrawal process by increasing the use of barbiturates and pain killers which only contributed to his growing drug tolerance. Near the end, Jones would complain of a 105º F fever, he had to have a urinary catheter, and he could hardly walk and required assistance (Scheeres, 2011). When Marceline’s parents, Walter and Charlotte Baldwin, visited Jonestown in early November 1978, they were shocked by their son-in-law’s appearance. (Reiterman, 1982). It is possible that Jones experienced post-acute withdrawal symptoms for as long as he was without amphetamines. These included mysterious physical ailments, depression and suicidal ideation, and a lack of self-control.

There is no doubt that the severity of Jones’ substance abuse heavily influenced his and the community’s actions, including the decision to end the lives of more than 900 people, including 300 children. Drugs were not the sole influence on Peoples Temple and its leader at this time, but it is a part of the story that is only beginning to be examined. While Jones took “speed” to build his empire, his congregation found salvation from “the destructive mechanizations of narcotics” in Peoples Temple (Q930, The Jonestown Institute, 1972).

* * *

Jim Jones was nothing without his diverse congregation. Peoples Temple membership was made up of the college educated and the formerly houseless. It included children of all ages as well as elderly in need of care, Midwesterners and Californians, queer folks, the devout and the agnostic, and recovering addicts. Without the mostly Black labor of the congregation, Jones’ political influence, the community services for which he was lauded, and his profitable businesses would not have been possible.

One of the community services provided by Peoples Temple was a drug rehabilitation program endorsed by Walter Mondale and Jane Fonda (Wooden, 1981). Early California convert Deanna Mertle began to “listen intently” during a dinner conversation about a minister in Redwood Valley named Jim Jones who helped people with drug addiction. Deanna and her husband Elmer joined Peoples Temple but later defected and changed their names for their own safety to Jeannie and Al Mills as they were stalked and harassed by Temple members acting on Jones’ response to the perceived abandonment. The Mills would later create the Human Freedom Center for other refugees from unsafe groups (Mills, 1979).

Sitting on a park bench in Detroit on a sunny summer day in 1976, Odell Rhodes watched fellow heroin addict Jon Dine enter a church which was hosting an unfamiliar religious group arriving on tour buses from California. Odell had drugs to seek and cared little to know more about Peoples Temple, never really thought about Jon again until later that summer. That’s when Jon, literally clean and sober, appeared as a part of the Temple’s advance team to drum up attendance for Jim Jones’ arrival. Up to this point Odell had tried to manage his heroin addiction by switching to alcohol which, at that time, he considered the lowest form of addiction on the streets. He twice sought an inpatient recovery program but relapsed without the proper resources to assist him in maintaining his new sobriety, namely becoming employed. Jon Dine was living proof that through Peoples Temple, recovery was possible. “If they could do it for him,” Odell said to himself, “they could do it for me” (Feinsod, 1981: 89).

Larry Schacht hitchhiked his way to California and joined Peoples Temple, leaving behind a drug-filled life in Houston. Deanna Mertle, Larry’s one-time housemother in the Temple, said that he suffered from mind-altering hallucinogens, while others claim he had been addicted to heroin (Mills, 1979; Scheeres, 2011). Larry not only found recovery in the community of Peoples Temple, but he also discovered his desire to become a doctor. Because of his history with substance abuse, however, he was barred from American medical schools. Thanks to Jim Jones, however, Larry was able to get a foreign medical education. Jones also came to Larry’s aid in Guyana when concerns were raised over his certification – and his ability to practice medicine – in Guyana.

Leslie Wagner-Wilson experimented with drugs in her life before Peoples Temple, but it was her sister Michelle’s struggles with drug addiction that led to their mother joining the church around 1969. Michelle never really took to the rigid, demanding life of a Peoples Temple member like her sister Leslie and their mother (Wagner-Wilson, 2008). It would be interesting to learn how often people who sought recovery in the church’s rehabilitation program joined the church and stayed sober; stayed sober but did not join the church; or relapsed back into substance use.

Leslie Wagner-Wilson experimented with drugs in her life before Peoples Temple, but it was her sister Michelle’s struggles with drug addiction that led to their mother joining the church around 1969. Michelle never really took to the rigid, demanding life of a Peoples Temple member like her sister Leslie and their mother (Wagner-Wilson, 2008). It would be interesting to learn how often people who sought recovery in the church’s rehabilitation program joined the church and stayed sober; stayed sober but did not join the church; or relapsed back into substance use.

After three years in Peoples Temple, Garry Lambrev left the church in 1968 without the repercussions other defectors faced for abandoning Jones. Lambrev spent a couple of years exploring the gay scenes of San Francisco but, according to Micheal Bellefountaine, became “disenchanted with a drug-drenched culture that mired him in addiction and loneliness.” Garry returned to the loving, sobering arms of life in Peoples Temple (Bellefountaine, 2011: 08).

Stanley Clayton and Ronald Wayne Talley used heroin before joining Peoples Temple, as did Chris Lewis, Jones’ bodyguard who died in what appeared to be a “revenge style execution” on the streets of San Francisco (Serial 227, 1978; McGehee, 2022). Vernon Gosney and Monica Bagby also experimented with drugs prior to finding a new life with Peoples Temple (Rohrlich, 2021).

What was it about life in Peoples Temple that allowed Odell Rhodes and others to not only get sober but stay that way? Life in Peoples Temple meant – for better or worse – you were always busy, you were always exhausted, and you were never alone. There simply was no time to drink or do drugs. Jones’ insatiable hunger for control meant that anyone breaking rules, or relapsing, was caught and made to face the rest of the Jonestown community over their transgressions. Communal housing, dining facilities, and medical services met their basic needs, and the bright, joyous, loving Peoples Temple community met some of their psychological needs as well. The lack of freedom ironically created freedom from substance dependence, a lot like inpatient drug rehabilitation programs. Odell Rhodes learned in his two recovery attempts that detoxing or stopping using wasn’t as difficult as trying to find a place to live without a job, or trying to find a job after years of living on the streets, or trying to find resources to help him rebuild his life after inpatient rehabilitation. Many addicts in these situations return to drugs and alcohol to manage the emotional weight of their current situations (Feinsod, 1981).

What was it about life in Peoples Temple that allowed Odell Rhodes and others to not only get sober but stay that way? Life in Peoples Temple meant – for better or worse – you were always busy, you were always exhausted, and you were never alone. There simply was no time to drink or do drugs. Jones’ insatiable hunger for control meant that anyone breaking rules, or relapsing, was caught and made to face the rest of the Jonestown community over their transgressions. Communal housing, dining facilities, and medical services met their basic needs, and the bright, joyous, loving Peoples Temple community met some of their psychological needs as well. The lack of freedom ironically created freedom from substance dependence, a lot like inpatient drug rehabilitation programs. Odell Rhodes learned in his two recovery attempts that detoxing or stopping using wasn’t as difficult as trying to find a place to live without a job, or trying to find a job after years of living on the streets, or trying to find resources to help him rebuild his life after inpatient rehabilitation. Many addicts in these situations return to drugs and alcohol to manage the emotional weight of their current situations (Feinsod, 1981).

Odell was happy in Jonestown. He taught the Temple children, enjoying arts and crafts with them. He came to love these children. He later worked in the medical unit during hours that allowed him to miss out on interminable evening meetings. But on November 18, 1978, Odell witnessed his beloved pupils succumb to the agonizing death of cyanide poisoning before he made his escape. He was pretending to look for a stethoscope to assist in the final White Night, when he encountered Stanley Clayton, another former addict also escaping death (Feinsod, 1981). Earlier that day, Leslie Wagner-Wilson, her son Jakari, and a small group of others left Jonestown on what they said was a picnic breakfast, and made their way to Matthews Ridge, 28 miles away (Wagner-Wilson, 2008).

“Vernon Gosney and Monica Bagby, Please help us get out of Jonestown.” (Scheeres, 2011: 212) That’s what the note said that Vernon handed to the person he thought was Congressman Leo Ryan but was, instead, NBC reporter Don Harris. A child nearby noticed the exchange and loudly announced it to everyone within earshot. Vernon and Monica were not high-ranking members of the Temple, but the discovery of their note and their desire to leave with Ryan led the NBC News crew to push Jones much harder about Peoples Temple members’ safety in Jonestown. This note was also the first sign for Ryan and his aides that some members really did wish to leave Jonestown. Most importantly, it created the opportunity for the Parks and Bogue families to admit they wanted to return to the United States. The loss of these two families that had been devoted to Jones from very early on would have been a massive blow to Jones’ fragile state of mind (Bellefountaine, 2011).

Temple doctor Larry Schacht died with his patients in Jonestown. Odell lost every friend he had in the world, along with the children he came to love through his teaching job. He was not alone in that regard. All the survivors lost parents, lovers, babies, aunts and uncles, people they’d known and loved for years. This is trauma on a scale that most of us will never have to comprehend.

Temple doctor Larry Schacht died with his patients in Jonestown. Odell lost every friend he had in the world, along with the children he came to love through his teaching job. He was not alone in that regard. All the survivors lost parents, lovers, babies, aunts and uncles, people they’d known and loved for years. This is trauma on a scale that most of us will never have to comprehend.

Jonestown survivors and Temple members in Georgetown were quarantined in the group’s Lamaha Gardens headquarters or the Park Hotel in Guyana’s capital city, while the Guyana Defense Force and law enforcement officials scrambled to determine if anyone else might be in danger. Their jobs were complicated by rumors flew about a hit squad supposedly consisting of members of the Jonestown basketball team who were in Georgetown for a tournament.

Things only got worse from there as sensationalized media coverage reduced the hundreds of Peoples Temple members to crazed followers of a madman’s death cult. Addicts who found recovery in Peoples Temple also lost their long-term inpatient drug rehabilitation program. They would return to the lives they left behind, which had been shattered by the exclusionary world Jones created. They had given everything to the Temple and now lacked any funds for a roof over their heads. Additionally, job seekers were stigmatized by hiring departments anytime they dared explain the gap in their resume with the truth about their membership in Peoples Temple. Dr. Hardat Sukhdeo counseled the survivors prior to their repatriation to the United States and told Odell Rhodes that it was likely he would relapse. As Odell responded, “there was no way I was ever going back to drugs – no way in hell” (Feinsod, 1981: 216).

Odell sat on a bench in a park. It was the same bench in the same park where he’d first watched Jon Dine walk away from heroin, the same place where he’d encountered a strange religious group setting up in the church and decided to make another attempt at a new life in recovery. Just like the summer of 1976, Odell was high on heroin. It was early in 1979, only about six weeks since Odell insisted there was “no way in hell” he was going back to drugs. Only half a year later, in June 1979, Odell’s substance abuse had increased to the point where complications from an injection site in Odell’s neck brought him close to death that he took drastic action. He left Detroit and went to San Francisco where he found a new life and recovery from his heroin addiction (Feinsod, 1981). Odell, a U.S. Army Vietnam veteran and former teacher of children, passed away in 2014 at age 71.

Stanley Clayton served time in an Oakland prison for domestic violence where he was introduced to crack cocaine, and his struggles with addiction has lasted for decades (Moore, 2018a). Vernon Gosney and Monica Bagby, whose note to Leo Ryan set the events of November 18 in motion, both struggled with drug addiction, although Gosney recovered sufficiently to have a long career in law enforcement (Gosney, 2006). Monica died on June 14, 2009. Vernon passed away January 31, 2021, from cardiac bypass surgery complications.

Leslie Wagner-Wilson discovered crack-cocaine while trying to create a life after Peoples Temple for herself and her children. Her monthly budget included $300 for drugs, which is just over $1,000 adjusted for inflation from 1980 to 2025. Drug-seeking and the illicit activities it can lead to found Leslie spending time behind bars. Despite the fact that “drugs were readily available inside,” Leslie used her time to free herself from active addiction (Wagner-Wilson, 2008:151). Leslie’s strong spirituality, love for her children, and a healthy community help her maintain her sobriety.

Substance abuse is not limited to those survivors who experienced it before joining Peoples Temple. Survivors were left to wrestle with emotional fallout of losing everyone they loved. In one interview after Jonestown, Mike Touchette told of how “free-basing cocaine” with his fellow line cooks caused his wife to leave him when she found out about the drug use. Touchette was one of the first pioneers to carve the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project out of the Guyana jungle, a task that he took to with poise and assurance, and that brought him immense pride. Upon the condition that he commit to attending a Christian church, his wife reunited with him, now joined by their daughter. Mike’s relationship with organized religion fluctuated through the years, but he remains what he calls “spiritual” and apparently free from substance addiction (Klapperich, 2021).

Herbert Newell was tasked to take the Temple boat Cudjoe down Kaituma River with Clifford Geig the morning of November 18. As they boarded, Ed Crenshaw, who had driven them over, made a strange comment, telling the two men “that by the time we returned the next day, he and the others would be dead.” Herbert was introduced to cocaine by a former member of Peoples Temple after returning home to the United States. After five years of active addiction, Herbert cleaned up and told his story of recovery on a 1988 episode of the Oprah Winfrey Show. Six years later Herbert fell back into the arms of addiction, where he spent the next decade of his life. Herbert found recovery again in 2006, as well as renewed and deepened relationships with his children and grandchildren (Newell, 2010).

Stephan Jones only knew life in Peoples Temple. While he and his adopted siblings – their parents’ rainbow family – did enjoy special privileges for being the children of Jim Jones, they were otherwise raised in the volatile world Jones created. Stephan’s childhood included witnessing his father’s adulterous relationships and emotional manipulation, physical abuse by other church members at his father’s command, and his father’s dependence on amphetamines and barbiturates. Even after Stephan almost overdosed on Jones’ stash of Quaaludes, his dad made no attempt to hide his drugs from his son. Stephan is the adult child of an addict and, as many of us do, he developed an addiction to substances in adulthood, becoming a heavy cocaine user (Wright, 1993). I believe that Stephan’s recovery from addiction opened his eyes to addiction’s role in his dad’s choices, including the ways addiction played a role in other parts of his father’s personality.

* * * * *

In The Urge: A History of Our Addiction, Carl Erik Fisher explains society’s burgeoning medically-focused understanding of addiction and recovery in a way that also applies to our evolving understanding of Peoples Temple. “Overly simplistic attempts to reduce complex phenomena have misled more than they have helped” (Fisher, 2022: 57). Reductionist interpretations of Peoples Temple provide a quick, clean, easy answer that satiates the casually curious and dominates society’s collective understanding of the church. They mislead us into believing that we are invincible to “blind fanaticism” or “drinking the Kool-Aid” by stripping members of the complexity of their situations before, during, and after Peoples Temple. Simplistic and demeaning terms for addicts – such as winos, crackhead, druggie, and junkie – similarly mislead us by equating addiction with homelessness, race, and class, blinding us to the ways addiction appears in our lives and the lives of our loved ones. These terms also stigmatize substance abuse, which can make it harder for an addict to genuinely consider seeking recovery. The stigma of alcoholism was the early reason for the “Anonymous” in AA. Unfortunately, the stigma-driven anonymity reduces the opportunity for people in active addiction to see the recovering addicts in their community, living examples that recovery is possible for someone like them, as Odell Rhodes saw in Jon Dine.

Because addicts sharing their stories are vulnerable, they need to find a group in which they feel seen and safe. Having an organization also helps to de-stigmatize what it means to be an addict, and an addict in recovery. This sense of community is key to substance abuse recovery and features heavily in Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-Step programs. Community and mutual aid were central to the Washingtonian Homes of the late 1800s, one of America’s earliest forms of an inpatient rehabilitation facility and an early predecessor to AA (Fisher, 2022). Survivors of Peoples Temple have also found a form of recovery in creating a new community amongst themselves as they navigate the passing of time since the event that utterly destroyed their world. The Jonestown Institute website offers survivors and researchers an online space to share their experiences, interpretations, and reflections. It also makes available to the public the names, photographs, and records of the Jonestown dead. Collectively, researchers and historians preserve Peoples Temple as the community it was, despite the growing true crime genre continuing to center the sensational story of Jim Jones, the crazed cult leader that convinced hundreds of people to kill themselves and others on November 18.

New and different interpretations of Peoples Temple broaden our understanding of the complex phenomena that was the fulfilling, yet destructive life spent following Jim Jones: the integrationist, the church leader, the change-maker, the God, the Father, the addict. Addiction haunts the story of Peoples Temple and the deaths of 918 people. Sharing these addiction stories opens us to community, which is vital to recovery. Centering stories of addicts in interpretations of Peoples Temple and other topics of interest will create a way for audiences to identify with characters experiencing substance abuse in the hope that they’ll recognize the ways in which addiction appears in their lives and the lives of their loved ones. I can say from lived experience that reading testimonies from and about other addicts, including those in Peoples Temple, absolutely has the potential to save lives.

References

Bellefountaine, M., & Bellefountaine, D. (2011). A Lavender Look at the Temple: A Gay Perspective of the Peoples Temple. iUniverse.

Feinsod, E., & Rhodes, O. (1981). Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown, the Only Eyewitness Account. W. W. Norton.

Fisher, C. E. (2022). The Urge: Our History of Addiction. Penguin.

Guinn, J. (2017). The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. Simon and Schuster.

Autopsy, James Warren Jones (1978). (RYMUR 89-4286-2178). Federal Bureau of Investigation. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/JimJones.pdf

Johnston Kohl, L. (2014). “Remembering Odell Rhodes,” October 7. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=61588

Layton, D. (1999). Seductive Poison: A Jonestown Survivor’s Story of Life and Death in the Peoples Temple. Anchor Books.

McGehee, F. M., III. (2022). “Who was Chris Lewis?” March 25. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=113980

Medical Records. (n.d.). In The Jonestown Institute (RYMUR 89-4286-J-2). Federal Bureau of Investigation. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13761

Medical Records (n.d.). In The Jonestown Institute (RYMUR 89-4286-J-1). Federal Bureau of Investigation. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=129117

Moore, R. (2018a, March 15). Back to the sources! Jonestown Journal. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=81939#jtjournal11.

Moore, R. (2018b). Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Newell, H. (2013). “The Coldest Day of My Life,” July 25. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=30312.

Q734 Transcript (1978). Trans. R. Arquette. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27567.

Q930 Transcript (1972). Trans. F. M. McGehee. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=60644.

Gosney, V. (2022). Reflections and Articles. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=17061.

Reiterman, T. (2008). Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People. Penguin.

Rohrlich, J. (2014). “How Did This Happen, and How Did I Not See It Coming?” Hazlitt, December 10. https://hazlitt.net/longreads/how-did-happen-and-how-did-i-not-see-it-coming.

Scheeres, J. (2011). A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival at Jonestown. Simon and Schuster.

Touchette, M. (2021). Interview by K. Klapperich, September 22. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=111238.

Wagner-Wilson, L. (2009). Slavery of Faith. iUniverse.

Wooden, K. (1981). The Children of Jonestown. McGraw-Hill Companies.

Wright, L. (1993, November 14). “Orphans of Jonestown.” The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1993/11/22/orphans-of-jonestown

Yates, B. (2013). “Murder by Thorazine: A Look at the Use of Sedatives in Jonestown, October 13. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=40232.

Yates, B. (2014). “The Nursery and West House: Tracing the Path of Barbiturates in Jonestown, October 10. The Jonestown Institute. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=61653.

(Author’s note: I am a recovering alcoholic who began studying Peoples Temple in 2019 when I began my sobriety journey. The focus of my work is addiction’s role in the Temple story and I am in the outlining stage of a future book. I am a Park Ranger at a State Historic Park, a Certified Interpretive Guide through the National Association for Interpretation, and I am leading the development of an accessible, virtual children’s education program in my agency.)

(Editor’s note: Brittni Criglow’s other article in this edition of the jonestown report is The Definitive Guide to Cyanide in Jonestown.)