[Editor’s Note: Landon Weber wrote this paper for Prof. Alexandra Prince’s class on Peoples Temple and Jonestown at Skidmore College in the Spring of 2025.]

If somebody in the 21st century knows anything about Peoples Temple, it is likely the only thing they know about it is the mass death event at Jonestown, Guyana, on November 18th, 1978. When the topic came up, one peer simply asked “That’s the kool aid cult right?” and after confirming that Peoples Temple is the group usually described as such (albeit reductively), he responded “Yeah, fucked up stuff.”[1] This sort of response illustrates the lack of wide-reaching media coverage and analysis of Peoples Temple, and especially the lack of further coverage outside of sensationalist headlines resulting from the events at Jonestown, such as the TIME cover barely more than two weeks after the final White Night. Not only did that type of coverage of Peoples Temple effectively put a permanent note on its reputation and history, it also spawned stereotypes and tropes that persist even to this day in things such as movies and TV shows entirely unrelated to Peoples Temple, as well as (unintentionally) rewriting the history of the Temple by association.

If somebody in the 21st century knows anything about Peoples Temple, it is likely the only thing they know about it is the mass death event at Jonestown, Guyana, on November 18th, 1978. When the topic came up, one peer simply asked “That’s the kool aid cult right?” and after confirming that Peoples Temple is the group usually described as such (albeit reductively), he responded “Yeah, fucked up stuff.”[1] This sort of response illustrates the lack of wide-reaching media coverage and analysis of Peoples Temple, and especially the lack of further coverage outside of sensationalist headlines resulting from the events at Jonestown, such as the TIME cover barely more than two weeks after the final White Night. Not only did that type of coverage of Peoples Temple effectively put a permanent note on its reputation and history, it also spawned stereotypes and tropes that persist even to this day in things such as movies and TV shows entirely unrelated to Peoples Temple, as well as (unintentionally) rewriting the history of the Temple by association.

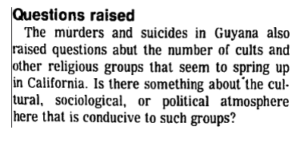

Prior to 1978, media coverage of Peoples Temple was relatively in favor of Peoples Temple as a whole. The group was often praised for their commitment to social activism and racial integration, as well as philanthropy for causes they supported. One article from the Chicago Defender in 1974 is a story about Jim Jones aiding the defense of three Black men accused of raping a White woman. After outlining the events themselves, the article discusses what Peoples Temple has done to support the three men (as well as what they are considering doing) and how Jones has “been a tireless fighter for civil rights and equal justice for 25 years,” not to mention his adoption of children from multiple racial backgrounds.[2]

Prior to 1978, media coverage of Peoples Temple was relatively in favor of Peoples Temple as a whole. The group was often praised for their commitment to social activism and racial integration, as well as philanthropy for causes they supported. One article from the Chicago Defender in 1974 is a story about Jim Jones aiding the defense of three Black men accused of raping a White woman. After outlining the events themselves, the article discusses what Peoples Temple has done to support the three men (as well as what they are considering doing) and how Jones has “been a tireless fighter for civil rights and equal justice for 25 years,” not to mention his adoption of children from multiple racial backgrounds.[2]

Another article, this one from the Los Angeles Sentinel in 1973, is a commendation of Peoples Temple for their commitment to free speech, again in the form of philanthropy. Like the article in the Defender, the money is going towards the defense of journalists who refuse to reveal their sources.[3] Not only that, Peoples Temple made a request when submitting the money that they not be acknowledged for doing so, stating that it was a demonstration that “…there are churches… which are not connected with the institutional press, also do indeed care about this threat to freedom of speech, press, and conscience.”[4] Pieces like these, at the time, gave the impression that Peoples Temple was a group worth following, even if not literally, due to their good nature and commitment to equality and liberty.

This is not to say that Peoples Temple did not have its dissenters. There are two major exceptions to the good vibes that PT were putting out: the first was a series in the SF Examiner, written by Reverend Lester Kinsolving and partially published in September 1972. The series starts with the title “The Prophet Who Raises The Dead,” discussing the belief among Temple members (and claims by Jones himself) that he could resurrect the dead, amongst other “equally amazing powers”[5] before then going into the more tangible aspects of Peoples Temple, such as their assets and notably armed security team. The explanation that the Temple offers for the security is as a necessity due to the number of threats and harassment that they have continued to receive.

This is not to say that Peoples Temple did not have its dissenters. There are two major exceptions to the good vibes that PT were putting out: the first was a series in the SF Examiner, written by Reverend Lester Kinsolving and partially published in September 1972. The series starts with the title “The Prophet Who Raises The Dead,” discussing the belief among Temple members (and claims by Jones himself) that he could resurrect the dead, amongst other “equally amazing powers”[5] before then going into the more tangible aspects of Peoples Temple, such as their assets and notably armed security team. The explanation that the Temple offers for the security is as a necessity due to the number of threats and harassment that they have continued to receive.

Kinsolving’s writing in this piece does not come across as necessarily condemnatory, although it does feel like a rather skeptical eye, and with relatively valid reason. No matter how good of a humanitarian cause somebody runs, claims of revivification are usually a cause for further investigation, which Kinsolving is happy to provide. Some of his other questionable parts of PT include their finances, with their “grand total income” for the 1972 fiscal year being listed at just shy of $400,000[6] (which would translate to around $3,000,000 today), as well as the secrets behind Jones’ ability to glean extraordinary details about somebody. The Johnson family, former PT members who submitted an affidavit for another incident involving the Temple officiating a wedding for their daughter, a minor at the time, also wrote that Jones “Uses people to visit potential church members, noting anything personal in the house… Then, when they show up in church, he tells them things about their ailments and the kinds of pills they take.”[7]

While both of these are undeniably extremely shady practices, there isn’t necessarily anybody being harmed, as far as people were aware. That feeling changed when Kinsolving’s fourth article was published on September 20th, 1972. In it, he brings up a recent suicide by a former member of PT, Maxine Harpe, and some unsettling circumstances around it. Kinsolving wrote that he spoke to Mrs. Harpe’s sister, and she claimed that “unidentifiable persons from People’s Temple had occupied her sister’s house and ransacked it.”[8] As the article progresses, the implication goes from breaking and entering to what may be fostering a potentially terroristic attitude by Tim Stoen, one of the Temple’s attorneys.[9]Kinsolving ends this article with words from a Reverend Mr. Taylor, saying “For these reasons and because I sincerely believe more questionable activity is going on, I do request that your office conduct an investigation.”[10] Before the next articles could be published, the Examiner decided to drop them. Whether it was due to picketing and protest by members of Peoples  Temple or simply because the series had not garnered enough interest for the Examiner to see it as worthy of continuing is still unclear, although some theorize that it was the latter.[11] In her article discussing the matter of Peoples Temple’s relationship to the press, Cheryl Coulthard also posits the theory that Kinsolving’s quick reporting may have even left the Examiner the target of lawsuits.[12] Lester Kinsolving’s son, Tom (who would later go on to run a blog titled “Jonestown Apologist Alert”), claimed it was due to corrupt media and other authorities,[13] and while there is nothing to say that is definitively the reason why, there is some credence to the claim. Due to Jones’ message of racial harmony and social justice, he was “the perfect asset to San Francisco’s liberal establishment. He donated to charities, promoted racial equality, and could raise large crowds for any political event”[14]

Temple or simply because the series had not garnered enough interest for the Examiner to see it as worthy of continuing is still unclear, although some theorize that it was the latter.[11] In her article discussing the matter of Peoples Temple’s relationship to the press, Cheryl Coulthard also posits the theory that Kinsolving’s quick reporting may have even left the Examiner the target of lawsuits.[12] Lester Kinsolving’s son, Tom (who would later go on to run a blog titled “Jonestown Apologist Alert”), claimed it was due to corrupt media and other authorities,[13] and while there is nothing to say that is definitively the reason why, there is some credence to the claim. Due to Jones’ message of racial harmony and social justice, he was “the perfect asset to San Francisco’s liberal establishment. He donated to charities, promoted racial equality, and could raise large crowds for any political event”[14] That was the last major criticism of Peoples Temple to hit the press until the New West article “Inside Peoples Temple,” published in 1977 and written by Marshall Kilduff and Phil Tracy. The two detail Jim Jones’ upbringing, Peoples Temple’s rise to prominence, and their current status, before going right into the details. Several accounts of former Peoples Temple members, some anonymous and some not, offered a comprehensive teardown of some of Peoples Temple’s inner practices, according to former members. From physical abuse like public spankings,[15] catharsis sessions and humiliation[16] not dissimilar in concept to the Synanon Game, how the faith healings were put together,[17]financial domineering of its members,[18] and even calling Jones a white fundamentalist,[19] echoing Kinsolving’s alarm bells from five years prior, now worsened. The article’s final page concludes with one more heading: “Why Jim Jones Should Be Investigated.”[20] Both in the article’s opening and closing, Kilduff and Tracy allude to Jones’ political connections, and in the latter, they imply that these politicians were complicit in Jones’ misdeeds.[21]

That was the last major criticism of Peoples Temple to hit the press until the New West article “Inside Peoples Temple,” published in 1977 and written by Marshall Kilduff and Phil Tracy. The two detail Jim Jones’ upbringing, Peoples Temple’s rise to prominence, and their current status, before going right into the details. Several accounts of former Peoples Temple members, some anonymous and some not, offered a comprehensive teardown of some of Peoples Temple’s inner practices, according to former members. From physical abuse like public spankings,[15] catharsis sessions and humiliation[16] not dissimilar in concept to the Synanon Game, how the faith healings were put together,[17]financial domineering of its members,[18] and even calling Jones a white fundamentalist,[19] echoing Kinsolving’s alarm bells from five years prior, now worsened. The article’s final page concludes with one more heading: “Why Jim Jones Should Be Investigated.”[20] Both in the article’s opening and closing, Kilduff and Tracy allude to Jones’ political connections, and in the latter, they imply that these politicians were complicit in Jones’ misdeeds.[21]

This New West article is at least partially credited with Peoples Temple’s move to Guyana coming on swift wings, with hundreds of people going down south the day the article was published. More specifically, the plans were made the night before, as Jones had connections that alerted him to the article’s inevitable publishing,[22] and this time it was too late to protest. From there, Peoples Temple’s fate is known. In the wake of the mass death event at Jonestown, “the media quickly rushed in to address the concerns of many Americans by exploring two questions: how did this happen and who can we blame?”[23] The sour press coverage around Peoples Temple from a year prior had greased the skids for an effectively unanimous conclusion from just about every media outlet, not just in the immediate aftermath but years to come: some version of “Jim Jones ran a brainwashing death cult.”

The reputation of New Religious Movements (NRMs) was already questionable in the United States during the mid-20th century. In an article by Sean McCloud, he divides the mid-late 20th century into “eras” for the public perception of NRMs that changed over time, and then affected the public perception of them. The first era, starting in the 1950s, was right in Cold War McCarthyism times, thus an aim to move against or at the very least observe anything perceived as “Godless communism,” including working-class movements and the Nation of Islam.[24] Some noticed this trend of NRMs popping up or setting up shop on the West Coast, leading to the term “California cults” circulating. The second era, from the 60s to early 70s, saw a rise in what some would consider New Age spirituality movements, coupled with the ongoing Civil Rights movement and protests of the Vietnam War, borrowing from Eastern traditions, neopaganism, and “Evangelical Jesus movements.”[25]

The final era, starting around the mid-70s into the 90s, is where Peoples Temple would be remembered most. McCloud describes this third era as what people tend to think of when you hear the word “cult” today: domineering or dictatorial leaders who could control their followers through mysterious techniques like brainwashing or hypnosis.[26] This narrative, while on the rise, exploded in usage after the mass death at Jonestown. The usage of ideas and phrases was effectively homogenous amongst several major outlets, including TIME Magazine and Newsweek,[27] language that would be mirrored years later at the siege of Waco and the Branch Davidians. That particular connection further reinforces the point that the events at Jonestown effectively redefined how mass media saw NRMs or anything remotely resembling one. Joseph Laycock narrows down three ideas in particular: “medicalization, deviance amplification, and convergence.”[28] Medicalization and deviance amplification are the two often associated with Peoples Temple, usually via things such as brainwashing combined with the need to be deprogrammed (in the case of medicalization) and leaders of NRMs having extremely shady pasts with things such as sexual history, substance abuse, and their “true colors” so to speak all being kept under wraps, both things that people observed after Jonestown.

The final era, starting around the mid-70s into the 90s, is where Peoples Temple would be remembered most. McCloud describes this third era as what people tend to think of when you hear the word “cult” today: domineering or dictatorial leaders who could control their followers through mysterious techniques like brainwashing or hypnosis.[26] This narrative, while on the rise, exploded in usage after the mass death at Jonestown. The usage of ideas and phrases was effectively homogenous amongst several major outlets, including TIME Magazine and Newsweek,[27] language that would be mirrored years later at the siege of Waco and the Branch Davidians. That particular connection further reinforces the point that the events at Jonestown effectively redefined how mass media saw NRMs or anything remotely resembling one. Joseph Laycock narrows down three ideas in particular: “medicalization, deviance amplification, and convergence.”[28] Medicalization and deviance amplification are the two often associated with Peoples Temple, usually via things such as brainwashing combined with the need to be deprogrammed (in the case of medicalization) and leaders of NRMs having extremely shady pasts with things such as sexual history, substance abuse, and their “true colors” so to speak all being kept under wraps, both things that people observed after Jonestown.

In her writing after the events at Jonestown, B. Alethia Orsot, a former member of Peoples Temple, spoke about how when the survivors returned to the United States, they were treated like untouchables, “an alien in my native land,” or a “brainwashes imbecile of the insane.”[29] It certainly was not helped by psychologists at the time saying things like “Destructive cultism is a sociopathic illness, which is rapidly spreading throughout the U.S. and the rest of the world in the form of a pandemic,”[30] as well as the growing influence of pop culture on the narratives around NRMs.

The book Snapping: America’s Epidemic of Sudden Personality Change presents a model of disease called “information disease,” which is like a regular disease but is not borne via germs or how other diseases work; rather, it is spread via information,[31] establishing a precedent for accusing something of being harmful information. Not only that, Snappingalso presents a narrative of “religious conversion as the result of mental trauma inflicted on the individual by a religious group,” which Laycock takes note of as bearing resemblance to the science fiction film Omega Man.[32] Another prominent example that Laycock cites as an example of this is the (supposedly) true story in Michelle Remembers, with its popularization of the idea of Satanic Ritual Abuse (SRA) and recovering repressed memories caused by a similar sort of trauma. He points out that the book, published in 1980, seems to pull from films like Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), The Wicker Man (1973), and the entire trope of Frankenstein’s monster.[33]

The book Snapping: America’s Epidemic of Sudden Personality Change presents a model of disease called “information disease,” which is like a regular disease but is not borne via germs or how other diseases work; rather, it is spread via information,[31] establishing a precedent for accusing something of being harmful information. Not only that, Snappingalso presents a narrative of “religious conversion as the result of mental trauma inflicted on the individual by a religious group,” which Laycock takes note of as bearing resemblance to the science fiction film Omega Man.[32] Another prominent example that Laycock cites as an example of this is the (supposedly) true story in Michelle Remembers, with its popularization of the idea of Satanic Ritual Abuse (SRA) and recovering repressed memories caused by a similar sort of trauma. He points out that the book, published in 1980, seems to pull from films like Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), The Wicker Man (1973), and the entire trope of Frankenstein’s monster.[33]

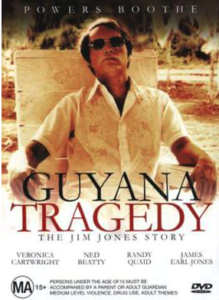

In a similar but still divergent way, Peoples Temple’s modern reputation has been constructed from not only mass reporting on its own, but also fictional narratives that get folded into the truth. CBS’ 1980 miniseries Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones is a prime example, as well as a good example of devious amplification and testing the line between what is historical accuracy and dramatization, such as introducing the story as “a dramatization of the life of Jim Jones,” then immediately following it up with “This is his story”[34] kind of juxtaposed against each other, but the idea of being a true story has a sort of recency bias due to presentation. More recent examples of documentary-style series include the History Channel’s Jonestown: Paradise Lost (2007) and A&E’s Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre (2018).[35] These have all been attempts to try and truthfully (albeit dramatically) recount the events at Jonestown, rather than alluding to it or calling on it as a sort of addition to the narrative. Any sort of show or film that has a plot or subplot with a cult in it is bound to allude to Jonestown in one way or another. The CSI episode “Shooting Stars” has an investigator speaking to a colleague about a matter pertaining to a cult leader, and mentioning that “Jim Jones and Charles Manson used sex to manipulate followers,”[36] and an episode of American Horror Story (fittingly titled “Drink the Kool-Aid”) has Jones compared to Kanye West (now Ye) as a kind of reference point for his personality and deviance in its own right.[37] Moving from Jones specifically, the idea of ingesting a mysterious liquid with the possibility of poison is also an obvious link, seen in such shows as Touched by an Angel, where the mention of Jones or Peoples Temple is not even needed due to the pervasiveness of the imagery.[38]

In a similar but still divergent way, Peoples Temple’s modern reputation has been constructed from not only mass reporting on its own, but also fictional narratives that get folded into the truth. CBS’ 1980 miniseries Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones is a prime example, as well as a good example of devious amplification and testing the line between what is historical accuracy and dramatization, such as introducing the story as “a dramatization of the life of Jim Jones,” then immediately following it up with “This is his story”[34] kind of juxtaposed against each other, but the idea of being a true story has a sort of recency bias due to presentation. More recent examples of documentary-style series include the History Channel’s Jonestown: Paradise Lost (2007) and A&E’s Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre (2018).[35] These have all been attempts to try and truthfully (albeit dramatically) recount the events at Jonestown, rather than alluding to it or calling on it as a sort of addition to the narrative. Any sort of show or film that has a plot or subplot with a cult in it is bound to allude to Jonestown in one way or another. The CSI episode “Shooting Stars” has an investigator speaking to a colleague about a matter pertaining to a cult leader, and mentioning that “Jim Jones and Charles Manson used sex to manipulate followers,”[36] and an episode of American Horror Story (fittingly titled “Drink the Kool-Aid”) has Jones compared to Kanye West (now Ye) as a kind of reference point for his personality and deviance in its own right.[37] Moving from Jones specifically, the idea of ingesting a mysterious liquid with the possibility of poison is also an obvious link, seen in such shows as Touched by an Angel, where the mention of Jones or Peoples Temple is not even needed due to the pervasiveness of the imagery.[38]

Despite the attempt of grounding in realism even with dramatization, these sorts of series often either toe the line or completely end up engaging in with Jonathan Z. Smith refers to as “the pornography of Jonestown.”[39] By this, Smith means the use of this tragic event as a sort of glorified backdrop and especially a dehumanization of the people involved, such as an odd fixation on “the details and conditions of the corpses.”[40] Seeing how a documentary style series or film engages with this idea can act as a sort of litmus test for the intentions of the series itself: is it to draw attention and propagate something people already know? Or is it to try and humanize the actual 913[41] people who died that day?

Where things get dicey is when narratives from different groups start to be combined together, not necessarily haphazardly, but in a way that does not differentiate between its sources. The previously mentioned episode of CSI that brings up Jones and Charles Manson as sexual deviants is centered on a group with “the cosmology of Heaven’s Gate,”[42] and an episode of Criminal Minds mixes the behavioral fragments of Peoples Temple and the Branch Davidians (the drills for the White Night and the standoff at the Waco compound).[43] Both of these examples contribute to a few problematic things: the interpretation of “the fictional and the historical in light of one another” the potential of “homogenization of these movements,” and the history of Peoples Temple and Jonestown being “refracted and re-envisioned through selective and decontextualized elements.”[44]

This is not to say that every piece of media about Peoples Temple, documentary or fictional, primarily focusing on it or vaguely alluding to it, is victim to the pitfalls and trappings listed here. Many documentaries do try to leave off on a somber or sincere tone, focusing not on the deaths on November 18, 1978, but rather on the people who lived there before and on those who were able to keep living on afterwards.[45] Even fictional accounts or things only alluding to the ideas connected to Peoples Temple and Jonestown are being shown in a more “human” way. Recent programs that utilize the cult leader character, such as the previously mentioned episode of American Horror Story, “show the leader to be sincere (even if deluded) in his beliefs,” and a kind of genuine belief in what they are doing,[46] rather than megalomaniacal egotists out for blood. There is nothing that can be done to undo the events of Jonestown, but people can continue to study what Peoples Temple was, what it was originally made for, and try to break the chains of the stereotypes that have been placed upon it. While the trend in recent media shows some degree of improvement towards society’s views of “cults,” there is a long way to go.

Bibliography

Conway, Flo and Jim Siegelman. Snapping: America’s Epidemic of Sudden Personality Change. 2nd edition. Stillpoint Press, Inc. January 1, 1995.

Coulthard, Cheryl. “The Peoples Press: The Evolution of the Media’s Treatment of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple.” Communal Societies 38, no. 2 (September 1, 2018): 195–210.

Greenfield, Gabrielle. “The Impact of Journalism on Jim Jones and Peoples Temple: Examining New West’s investigative report.” https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=64969 (October 29, 2015).

“Inside Peoples Temple,” New West Magazine, August 1, pp. 30-38, from California Historical Society, Moore Family Papers, MS 3802. Reprinted with the permission of the article’s authors, Marshall Kilduff and Phil Tracy.

Kinsolving, Lester. “The Prophet Who Raises the Dead.” San Francisco Examiner, September 17, 1972.

Kinsolving, Lester. “D.A. Aide Officiates for Minor Bride.” San Francisco Examiner, September 19, 1972.

Kinsolving, Lester. “Probe Asked of People’s Temple.” San Francisco Examiner, September 20, 1972.

Laycock, Joseph. “Where Do They Get These Ideas? Changing Ideas of Cults in the Mirror of Popular Culture.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Volume 81, no. 1 (March 2013): 80-106.

McCloud, Sean. “From Exotics to Brainwashers: Portraying New Religions in Mass Media.” Religion Compass 1, issue 1 (2007): 215-228.

Neal, Lynn S. “Jonestown on Television.” Nova Religio 22, no. 2 (2018): 137-144.

Orsot, B. Alethia. “Together We Stood, Divided We Fell” in The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown: Remembering Its People, edited by Rebecca Moore and Fielding McGehee III. The Edwin Mellen Press, 1989.

“Pastor-Legislator Join to Defend Men.” Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition), June 22, 1974.

“Record Commends Peoples Temple.” Los Angeles Sentinel, Jul 19, 1973.

Tidyman, Ernest. Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones. Directed by William A. Graham (1980; CBS Television, 1980).

Image Credits

“Cult of Death.” TIME Magazine, Volume 112, no. 23. December 4, 1978.

“Pastor-Legislator Join to Defend Men.” Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition), June 22, 1974.

“Record Commends Peoples Temple.” Los Angeles Sentinel, Jul 19, 1973.

Kinsolving, Lester. “The Prophet Who Raises the Dead.” San Francisco Examiner, September 17, 1972.

Kinsolving, Lester. “Probe Asked of People’s Temple.” San Francisco Examiner, September 20, 1972.

Kilduff, Marshall and Phil Tracy. “Inside Peoples Temple.” New West Magazine, August 1, 1977.

Knickerbocker, Brad. “Jones and the Peoples Temple: How did they gain influence?” The Christian Science Monitor, November 21, 1978.

Conway, Flo and Jim Siegelman. Snapping: America’s Epidemic of Sudden Personality Change. 2nd edition. Stillpoint Press, Inc. January 1, 1995.

Tidyman, Ernest. Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones. Directed by William A. Graham (1980; DVD. CBS Television, 1980).

Endnotes

[1] Username “tango!”, group Discord message with author, April 29, 2025.

[2] “Pastor-Legislator Join to Defend Men.” Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition), June 22, 1974.

[3] “Record Commends Peoples Temple.” Los Angeles Sentinel, July 19, 1973.

[4] “Record Commends Peoples Temple.”

[5] Lester Kinsolving, “The Prophet Who Raises The Dead.” SF Examiner, September 17, 1972.

[6] Kinsolving, “The Prophet Who Raises The Dead.”

[7] Lester Kinsolving, “D.A. Aide Officiates for Minor Bride,” SF Examiner, September 19, 1972.

[8] Lester Kinsolving, “Probe Asked of People’s Temple,” SF Examiner, September 20, 1972.

[9] Kinsolving, “Probe Asked of People’s Temple.”

[10] Kinsolving, “Probe Asked of People’s Temple.”

[11] Cheryl Coulthard, “The Peoples Press: The Evolution of the Media’s Treatment of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple.” Communal Societies 38, no. 2, (September 1, 2018), 208.

[12] Coulthard, “The Peoples Press,” 208.

[13] Coulthard, “The Peoples Press,” 208.

[14] Gabrielle Greenfield, “The Impact of Journalism on Jim Jones and Peoples Temple: Examining New West’s investigative report.” https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=64969, October 29, 2015.

[15] Marshall Kilduff and Phil Tracy, “Inside Peoples Temple.” New West, (August 1, 1977), 34.

[16] Kilduff and Tracy, “Inside Peoples Temple,” 34

[17] Kilduff and Tracy, “Inside Peoples Temple,” 35

[18] Kilduff and Tracy, “Inside Peoples Temple,” 35-36.

[19] Kilduff and Tracy, “Inside Peoples Temple,” 31.

[20] Kilduff and Tracy, “Inside Peoples Temple,” 38.

<[21] Kilduff and Tracy, “Inside Peoples Temple,” 38.

[22] Gabrielle Greenfield, “The Impact of Journalism on Jim Jones and Peoples Temple.”

[23] Cheryl Coulthard, “The Peoples Press,” 195.

[24] Sean McCloud, “From Exotics to Brainwashers: Portraying New Religions in Mass Media,” Religion Compass Vol 1. No. 1, (2007), 216.

[25] McCloud, “From Exotics to Brainwashers,” 216.

[26] McCloud, “From Exotics to Brainwashers,” 216.

[27] McCloud, “From Exotics to Brainwashers,” 222.

[28] Joseph Laycock, “Where Do They Get These Ideas? Changing Ideas of Cults in the Mirror of Popular Culture,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion vol. 81, no. 1 (March 2013), 84.

[29] B. Alethia Orsot, “Together We Stood, Divided We Fell” in The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown: Remembering its People, ed. Rebecca Moore and Fielding M. McGehee III (The Edwin Mellen Press, 1989), 105.

[30] Laycock, “Where Do They Get These Ideas?”, 89.

[31] Laycock, “Where Do They Get These Ideas?”, 90.

[32] Laycock, “Where Do They Get These Ideas?”, 90.

[33] Laycock, “Where Do People Get These Ideas?”, 91.

[34] Lynn S. Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” Nova Religio 22, no. 2 (2018), 138.

[35] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 138.

[36] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 139.

[37] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 139.

[38] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 139.

[39] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 140.

[40] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 140.

[41] The total death toll of the events at Jonestown as far as is known is 918, but this count does not include the five people who died at the Port Kaituma Airstrip, including Congressman Leo Ryan and those in his company.

[42] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 140.

[43] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 140.

[44] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 140.

[45] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 141.

[46] Neal, “Jonestown on Television,” 141-142.