A transcription project I undertook for the Jonestown Institute has evolved over the years into a valuable teaching engagement, offering my students a means to preserve and analyze historical events and stories for the benefit of researchers, survivors, and family members while asking critical questions about the ethics of knowledge production.

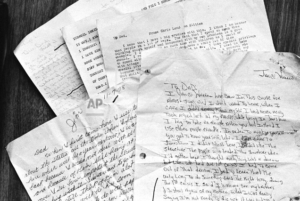

In 2022, I began to involve my undergraduate students at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York in the transcription of letters written by the residents of Jonestown to Jim Jones. These letters, recovered by the FBI in the aftermath of the tragedy, were labeled “Letters to Dad” during the RYMUR (Ryan Murder) investigation. At first, transcription was just one class activity on one day within my introductory American Religions course. I invited interested students to approach me after class if they wanted to continue the transcription work on a volunteer basis, and to my surprise and delight, several of them did. The next year, I was able to support two students as paid research assistants for their contributions. During Summer 2024, I oversaw the volunteer work of two students who contributed to the project. And, in Spring 2025, I developed a course solely dedicated to the study of Peoples Temple to engage more students in the study of a movement and history that has both deeply challenged and inspired me as a historian of American religions.

To date, more than 75 students have transcribed nearly 1,000 pages.

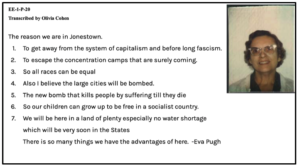

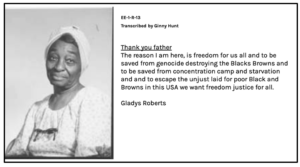

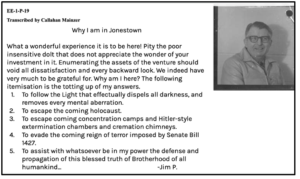

Our primary focus has been transcribing letters containing accounts and confessions about life at Jonestown. The letters provide unique insight into the varied racial and gendered experiences of Jonestown residents that cannot otherwise be accessed. Some of the letters reveal the mundane realities of life in Jonestown; others, the range of human emotions— resentments, jealousies, and attractions— that inevitably percolate in an intimate communal setting. Many letters provide a close look at the forms of knowledge and radical politics that were privileged in Peoples Temple. Others give insight into the dynamics of authority that Rev. Jones wielded. And several make clear the authors’ willingness to die for their community and the cause of socialism.

I view transcription work as a form of what I call deep reading. While some may assume it to be a form of tedious labor that requires little imagination and analytical capacity, in fact, transcription of the handwritten letters at Jonestown invites us to slow down and consider every word and phrase in relation to the whole text. Sometimes you might linger on the same word or phrase for several minutes, or longer. And, often, because the letters were penned in a radical socialist communal environment steeped in post-colonial African liberation politics, side investigations are necessary. Who was the leader of Zimbabwe in 1978? Right, that’s Joshua Nkomo.

I view transcription work as a form of what I call deep reading. While some may assume it to be a form of tedious labor that requires little imagination and analytical capacity, in fact, transcription of the handwritten letters at Jonestown invites us to slow down and consider every word and phrase in relation to the whole text. Sometimes you might linger on the same word or phrase for several minutes, or longer. And, often, because the letters were penned in a radical socialist communal environment steeped in post-colonial African liberation politics, side investigations are necessary. Who was the leader of Zimbabwe in 1978? Right, that’s Joshua Nkomo.

Transcription work can also empower students. As Fielding McGehee often reminds us, the students and I are often the very first individuals to read the letters since they were written in 1978 – a profound truth that can foster intimacy between the student-transcriber and the author’s words. The vast majority of the letter-writers lost their lives within months of putting their thoughts, emotions and insights onto paper, a realization that challenges us to be as faithful as possible in our transcription work. By making these letters accessible to all, we can elevate their words and experiences as a means to honor their memories, support the loved ones they left behind, and better assist researchers’ efforts to develop nuanced accounts of Peoples Temple.

As an educator, I see the value of engaging students in transcription work on multiple fronts – it provides them with unique first-person glimpses into a contested history and movement; it situates and empowers students as producers of knowledge; and, importantly, it prompts students to reflect on the power dynamics of producing and sharing knowledge about contested histories and lived experiences.

Time dedicated to in-class discussion of the transcription work is fundamental to our transcription process, a true example of what I understand collaborative learning to be. Students take turns reading their transcriptions while the rest of the class closely follows and offers input on words or phrases that were difficult to decipher due to the author’s unique penmanship, lack of literacy, or simply because there are oftentimes names or movements specific to 1970s radical liberationist politics that most people are unfamiliar with today. We also work on collaboratively annotating the transcribed letters and use them as lenses into the broader Peoples Temple and American experience.

Transcription and study of the Letters to Dad collection invites us to consider a variety of critical questions in Peoples Temple studies and the study of religion more broadly: How do we account for multiple sometimes contradictory perspectives? What voices are being privileged and what voices are being silenced? Who gets to define a movement or religion? Routinely, students are positioned as passive receptacles or consumers of knowledge in the classroom. Our project charges students with sharing and making accessible history as a means to reflect on how history is produced and disseminated.

Many students question if we have the “right” to read letters that were never intended for our eyes. I can’t say if this concern is ever entirely assuaged, but as you read the student reflection papers, I think it will become clear that their approaches to reading and transcribing the letters are far from voyeuristic. At the same time, the valid ethical concerns the students share prompt important questions that demand deeper reflection: Do we have a “right” to any of the personal and community histories we read about? How were those histories produced and shared? What are the broader ethical considerations of producing and sharing knowledge about people and communities we are not a part of? Where did the knowledge shared in all of the classrooms of our college come from? Who has access and who is restricted?

Students are asked to include a photo of the author at the end of their transcribed letters, often sourced from the Jonestown Memorial List. Our task is to represent the words and worlds of fellow humans, many of whom labored to build a society free from racism, classism, and colonialism – and most of whom lost their lives on November 18, 1978. Including a photo at the end of the letter serves to reinforce to the transcriber that the words in front of them were penned by a real person who lived a complex life of emotions, disappointments, frustrations, joys, and dreams, just as they do. Even in a class that privileges a human-centered lens of study, it can be easy to forget this human dimension.

Students are asked to include a photo of the author at the end of their transcribed letters, often sourced from the Jonestown Memorial List. Our task is to represent the words and worlds of fellow humans, many of whom labored to build a society free from racism, classism, and colonialism – and most of whom lost their lives on November 18, 1978. Including a photo at the end of the letter serves to reinforce to the transcriber that the words in front of them were penned by a real person who lived a complex life of emotions, disappointments, frustrations, joys, and dreams, just as they do. Even in a class that privileges a human-centered lens of study, it can be easy to forget this human dimension.

I am humbled to play a small part to support critical perspectives of Peoples Temple and extend my great thanks to Mac and Rebecca for facilitating our contributions and guiding our efforts.