(Editor’s note: This article is reprinted with permission from The Nation Magazine, January 12/19, 2009, p. 41.)

In 1977 hundreds of members of the Peoples Temple left California to join their leader, the Rev. Jim Jones, at his 3,800-acre compound in Guyana. Many were African-Americans who were drawn to the commune by Jones’s embrace of integration. One year later, US Congressman Leo Ryan and a small group of journalists flew to Jonestown to investigate reports of discontent there. When Ryan’s delegation was preparing to leave on November 18, 1978, Jones loyalists opened fire on the dirt airstrip; Ryan, three journalists and a commune defector were killed. That night, more than 900 Jonestowners drank cyanide laced grape Flavor Aid and died; Jones was later found with a bullet hole in his head. Journalist Tim Reiterman was part of Ryan’s delegation, and in 1982 he and John Jacobs published Raven, detailing the history of Jones and the Peoples Temple. Raven, which had been listed as the most in-demand out-of-print biography by Bookfinder. com, has been reissued by Penguin ($I8.95) for the thirtieth anniversary of the massacre. The book is a macabre rejoinder to the sign Jones hung above his throne in Jonestown: Those Who Do Not Remember The Past Are Condemned To Repeat It. –Christine Smallwood

Why is the life of Jim Jones still an important story?

What happened in Jonestown was tragic, and it’s important to understand that the people who joined the Peoples Temple did so for good reasons. They were mostly ordinary people who wanted to help. They created a family like dynamic as well as a commitment to various social ideals, especially racial equality and social justice.

The extent of Jones’s political power in California may come as a surprise to people who don’t know the history of the Peoples Temple. How did Jones become so connected?

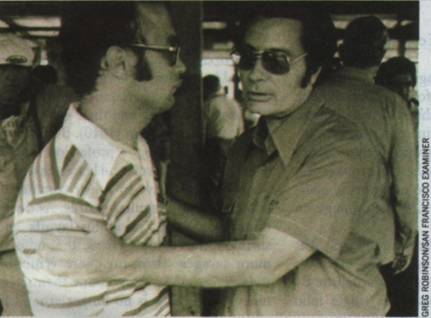

Jones acquired political power through assisting politicians, mostly in San Francisco, with campaign work. He had a reputation of being able to deliver people to rallies and other events at a moment’s notice. He also created the illusion that his church was much bigger than it really was. He claimed there were 20,000 or 30,000 members in California, but in fact there were about 3,000. He was credited with being instrumental in the election of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone, the DA Joseph Freitas and Sheriff Richard Hongisto – a relatively liberal slate that came into office [in 1975]. Moscone then rewarded Jones, who was pushing for an appointment, with the chairmanship of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission. When prominent political figures came to the Bay Area, Jones was there. He went on Walter Mondale’s private jet when Mondale came to San Francisco, and he got an audience with Rosalynn Carter before she became first lady. He was a most unusual Housing Authority chairman because he had bodyguards. His entourage attracted the interest of Marshall Kilduff, who was then at the San Francisco Chronicle. He eventually wrote a New West magazine piece about Jones [in August 1977], which was the first expose.

Raven includes two sections of photos that range from Jones as a child and young man to the bodies in Guyana. How do photographs help to tell this particular story?

The Jonestown photos were taken by Greg Robinson, who was there with me from the San Francisco Examiner and was killed on the airstrip. They convey, in a way my words could not, the tension that existed in Jonestown: defectors wanted to leave with Congressman Ryan and go back to the United States. The morning after Greg was shot, I took a photo, using one of his cameras, of his body, those of the others on the airstrip and the airplane that we were boarding when the gunfire broke out. We were later airlifted to a hospital in Washington, DC, by the military. A copy of the New York Times was brought into my room the next morning, and that photo on the airstrip of the plane and the bodies was large, front and center. It took up a big chunk of the front page. It brought home to me not just how important it was to have an image of what happened but also the magnitude of the event. I approached that trip as a local journalist working for a newspaper that didn’t circulate beyond Northern California, and suddenly the story became something much bigger, something incomprehensible that left people around the world pretty shocked initially but I think finally just baffled.

Why?

People have seized on the photos, and they’ve remembered the bloated bodies and the shooting at the plane. But they’ve never really come to understand why it happened. The answer lies in the psyche of Jim Jones. A lot of people dismissed him as a do-gooder, a liberal who went bad, but if you go back to his childhood and his adolescence, you can see the seeds of his madness and sickness. He was able to hide the negative, cruel and unbalanced aspects of his personality from many people. Some of them began to see through him and escaped his grasp. Others rationalized them or were so compromised themselves that they stayed with Jones until the end.

You recently left the Los Angeles Times, after nineteen years, to be the news editor for Northern California at the Associated Press, where you started your career. As a lifetime print journalist, what are your thoughts about the state of newspapers today?

I think it’s critical, regardless of the media platforms, that news organizations continue to ambitiously and aggressively pursue the most difficult stories. When news organizations are downsizing, scaling back and in some cases dying, the tendency is to abandon the tough stories, leave them to somebody else, go for the easy, quick, entertaining pieces that might be satisfying in the short term but don’t really enhance our understanding of the world in any meaningful way. The puzzle that newspapers are grappling with, of course, has been how to present news on the Internet and do it in a way that is profitable. I don’t think anyone’s figured that out yet. But as long as the content is good and serves the public, I think there will be a desire for it.