(Ed. note: The premier issue of The Living Word, the subject of this article, is on the Primary Sources page in both text and pdf formats.)

The Living Word was one of Jim Jones’ perhaps purposeful, though least lethal, dead-ends or – politely put – cul de sacs. This, the first serial publication attempted by Peoples Temple at the behest of our master, had its public origin on a Wednesday night in April 1972, a full moon in Libra. Jim had called me to the floor of the Redwood Valley Temple to account for a litany of transgressions, the most salient of which was that I had roughed up my former boyfriend, John Timmons, who only that morning had left PT forever, returning to Babylon by Greyhound bus. The punishment Jim meted out to me, partly in deference to my lack of defensiveness – or so I was led to believe at the time – was to put me in charge of the Temple’s magazine-to-be as its first (and perhaps last) Editor-In-Chief and to offer the opportunity to select whatever staff I thought could get the job done most effectively. Though I thanked him for his vote of confidence in my potential, I protested my lack of experience. Looking directly into my eyes without the proverbial dark glasses, he pointed out with dry equanimity that nobody else in our midst had this sort of experience either. In fact, there was one other, Penny Dupont, but she was even more certifiably crazy than I and, in any case, did not receive the marching orders. There was also a distinctly superior writer, Harriett Tropp, whose talents might have been tapped, but she was preoccupied by her legal studies in San Francisco.

While the catharsis session continued in the sanctuary, Jim Randolph took me to a back room where we were joined by John Harris to hear the specifics. Randolph informed me that he would play the role of publisher under a pseudonym. As it turned out, he played none at all, unless it was entirely underground. John would be responsible for the press runs as production manager. And, of course, I would be totally responsible for the contents.

In that extended moment, I had every reason to want to please everybody, particularly the deity-in-charge. From my perspective as a believer, God’s justice had been tempered by more than a small amount of mercy. I, a renowned slacker, was being offered an opportunity to rehabilitate myself and in the process to build real character as a facilitator, a leader of my peers. I was quite willing, I thought, to do whatever they might have in mind. But the challenge they posed took any prospective wind out of my sails. The product had to be ready to go to press in one month! I knew argument was out of the question, so I tried to accept my fate.

Reeling from this lightning appointment and the consequent assignment to create something out of nothing, and with no time to do it in, I woke up the next morning realizing that I barely knew where to start. As yet I had received no direct instructions relating to explicit content or even general message. And so I had to presume that what Jim wanted was the sort of publication about which he had spoken with increasing regularity in PT family meetings, one that could successfully convey our message of equality and cooperation, based on the teachings of Christ Jesus, the Buddha, as an alternative to the race towards war and planetary destruction, to be directed to those thousands of black folk who were making their ways to our doors or would hear about us soon enough from family, friends and acquaintances, perhaps because of the outreach of our magazine.

I didn’t have to be told that we weren’t to market Jim as a burnished image of his alleged reincarnation as Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, but I do have to admit that in my idealistic naiveté I actually thought our God might want an evangelical mouthpiece that would generate interest in what he often called “Divine Socialism” – dealing less in theory than in our actual practice – among those who had most to gain from a revolutionary change in the distribution of power. In retrospect, it’s obvious I failed to reckon with Jim’s cynicism as to what was possible, based on his understanding of people’s fundamentally selfish motives. Also in retrospect I have to give the devil his due. As active members, all of us knew much too well from repeated observation that most first timers came for healings and assorted gifts of his supposedly holy spirit; very few were able and willing to accept an opportunity to help build a new sort of heaven right here on earth; and so very few returned. Had I been able from the outset to acknowledge to myself that the unstated purpose of this magazine had to be the acquisition of money – in other words, the seduction of folks into paying for whatever tender mercies might be brought into their presumably miserable lives – my boot camp training might have been much less rough.

As it turned out, Jim could count on me to act as my own worst enemy. His decision to let me take total responsibility for selecting my own editorial crew ensured that I’d have nobody to blame but myself for negative outcomes. To be sure, my choices were in large part dictated by availability and skill, therefore limiting the pool to a very few. I didn’t know some potential candidates such as Laurie Efrein well enough to appreciate their capabilities, but most of those who might have helped were already over-committed to other endeavors. In any event, lacking time and previous experience, I quickly – no doubt impulsively – invited a group, composed largely of friends, to join me in this risky adventure. Almost without exception, those I selected had been participants in an informal socialist discussion group, which Jim had reluctantly authorized the previous fall, meeting in private homes, always monitored by at least two counselors and regarded by Jim and those close to him as “anarchists.”

I should have known that my pivotal “anarchist” recruit, Joyce Shaw, a former girlfriend, was still pissed off at me for replacing her with a man. She joined the staff as the principal of three assistant editors. I chose her for her critical faculties and nose-to-the-grindstone dedication to projects she’d undertaken in the past without complaint. The other two assistant editors I picked were Edith Roller, whose surviving journals might shed further light on the more opaque of our proceedings, and a bisexual Chilean-American artist/musician, Peter Wotherspoon, whose torture several years later for a second instance of child-molestation was to propel my final departure. Near-blind Patti Chastain, whom I had introduced to PT the previous year, gladly accepted the role of Art Director and served with distinction. As able a critic as anyone, Patti could tactfully but firmly nail real problems and suggest reasonable solutions. She also wisely refused to get involved in the power struggle that quickly developed for control and, as much as was possible, tried to mediate disputes.

With my permission, Joyce recruited her new boyfriend (and future husband), Bob Houston, as photography editor. I should have known that with friends like these I wouldn’t need enemies, but I couldn’t think of anyone else with the photographic skills that Bob, offspring of the chief AP photographer in San Francisco, had in spades. It was Bob’s mysterious death in the Southern Pacific railroad yard in San Francisco four years later that led his dad to ask an influential friend named Leo Ryan to look into the political ambitions of Jim Jones. Larry Schacht, the doctor who later dispensed the poison, served as a second photographer, but I hardly recall his presence, probably because it was laudably reflected in camera work rather than ideological or literary disputes, the forte of Joyce and Bob, my equals – as time was to prove – in doctrinal inflexibility, camouflaging ego needs on all our parts to come out on top of whatever pile of shit in which we happened to be working.

Our first few editorial meetings were mercifully brief in deference to the need to get the articles written. Edith, a former English teacher at San Francisco State and modern day spinster of near sixty, took responsibility for the keynote article with childlike enthusiasm, introducing Jim Jones to the reader, and fortunately not much more. Though she had expository skills, she had no understanding whatsoever of Christian fundamentalists or, for that matter, individuals with any religious inclination, and tended when permitted towards overblown Marxist rhetoric. Brought up as an atheist in a socialist mining family in Leadville, Colorado, she could barely muster an anthropological interest in those drawn by our Savior’s special “gifts.” I had to rewrite whatever she wrote, which in the end was removed on Jim’s orders as much too political. Peter stayed in the background, a silent partner who put up little resistance to whatever the loudest and most persistent voices – especially those of Joyce and Bob Houston – demanded, except to send me sympathetic glances with his deep blue eyes when I was being grilled on various hot seats over the course of the next several months. I don’t recall that he wrote anything, though he may have helped Patti with the art work, and certainly did assist with the interviews of those who’d been healed, including Mark Cordell, of whom more later.

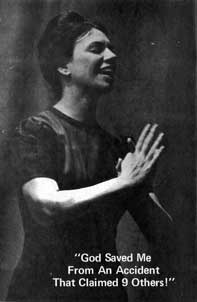

In any event, my title of editor-in-chief proved to be a nasty joke. What it quickly came to mean in practice was that I wrote almost all the copy. The truth be told, nobody else on the staff had any available time, and I was desperate to prove my worth. Unemployed myself, ordered by Jim to look for a paying job at the same time I was given command of the magazine, I sat at a kitchen table day after day and alternated between reading the New Testament, searching for justification for what I was typing, and transforming the raw testimonies of healings and salvation from accidents – submitted at staff request or taken from interviews – into convincing arguments to come and visit or at least tune in to our pastor’s weekly radio programs.

Mention needs to be made of another one of several provisos that Jim had attached as a condition of my rehabilitation, because it powerfully impacted the production of The Living Word. At the time of my appointment to the editorial position, Jim made me a “probationary” counselor and directed me to attend all private Monday night sessions of Council, which usually met in the Redwood Valley home of Tim and Grace Stoen. Thus with utter diplomacy and strategic brilliance, Jim Jones managed to make sure that I would be carefully watched and my every movement circumscribed while I was in the process of putting together something as potentially important (and dangerous) as a magazine bearing his imprimatur. It was a simple but effective ploy: Council would play bad cop; He – as ever – would continue to play the role of the suffering Messiah, who would forgive and offer one more chance to even the blackest of anarchist sheep like yours truly.

It was at the first of these private counseling sessions that I learned much more of what was expected. There would be no mention anywhere in the text – certainly nothing explicit – about Marxism-Leninism. In fact, much to my disappointment and that of the staff I had appointed, there was to be no overt political content whatsoever. As a writer, I would confine myself to generalities about our good works, and reinforce them with ample biblical quotations, preferably lifted from the New Testament and make sure that the rest of the staff did likewise. In a subsequent private conversation, Jim encouraged me to study not only the Christian Bible but the magazines of other purported faith healers, especially Oral Roberts, Kathryn Kuhlman and Reverend Ike. It was critical that I get their lingo down.

Our God Himself modestly suggested the title, The Living Word, a risible touch, however unconscious, of high camp that none of us expressed any amusement about at the time. It derived from the biblical quotation Jim liked most to cite: “How can you hear without a preacher? And how can he preach lest he be sent?” The choice of it was closely related to the key ideological point for which he wanted us to find justification, the seeker’s need for a God-in-the-Body rather than a supposedly holy book or Sky God in order to achieve salvation, and its corollary, the Beneficent Dictatorship of God. Given explicit instructions to avoid direct politics, it was going to require intellectual legerdemain to present the account of Pentecost from the Book of Acts as the basis for the communist nature of the Christian Church, the next most important point he wished His magazine to convey and one which, I’m afraid, we failed to accomplish, certainly in the premiere issue. Finally he wanted us to find biblical grounds for acceptance of the law of karma – and its consequence, reincarnation – and to find some way, however subtle, to introduce it to presumably fundamentalist and often barely literate readers. And I was to do this with a single consideration in mind, that I was not to expect too much from a prospective audience whose blind ignorance could not underestimated.

So that I might best be able to cover his healings and all matter of public revelation, Jim afforded me the rare privilege of taking notes for editorial use during all meetings. Though these notes disappeared years ago in some waste paper basket or other, at the time they and the close observation on which they were based – and the Bible verses, of course – proved invaluable in what I was helping to compose. Looking back, I just wish Jim had possessed the guts to have us publish these “Quotations from Chairman Jim.” Fortunately, it’s not too late. Somebody soon needs to do that while memories are still alive. Perhaps that will be me or perhaps that will be you, Dear Reader. I know that Laurie Efrein-Kahalas has – or had – much of the useful material and an archival memory to boot. If it happens, I hope that, in respect to what PT was all about, we do it together.

Looking at the front cover of that first issue more than 33 years later, I’m struck by the glance of Jim, his eyes averted from the viewer, looking down -it would seem – at the place on the pulpit where he was putting down his dark glasses. Or perhaps he was about to pick them up and place them over his eyes before looking out over the presumable assemblage, containing many with mixed motives and some with evil intent. So he led us to believe in any case. If you wanted to look into his eyes, you would have to seek him out, beginning with the contents of that first issue, some 40 pages in length.

We still had a lot of work left to do when the deadline arrived as a heavy blunt instrument over the full moon in Scorpio in early May. I, at least, experienced it as such. Having worked hard to produce almost all the copy, enough to fill our first issue, supplemented by Edith Roller’s Marxist encomium to Chairman Jones, I expected at least momentary relief from mounting pressure. Unfortunately, it was all a first draft. Nobody but me had even read the shit. Driving down to LA that weekend, Joyce Shaw and Bob Houston finally had an opportunity to do so and were aghast, particularly as I was not even with them but staying back in Ukiah on some flimsy excuse. What I told nobody was that I was moseying down to the Bay Area to check out – and be checked out – by my childhood best friend, former and future lover, who after a long absence was becoming both available and unavoidable.

The following Monday night council meeting at the Stoens left me feeling too frightened to get depressed. Several counselors screamed at me for my failure to produce a finished photo-ready copy. Jack Beam exclaimed that I needed some experience in a forced labor camp. As Jonestown was not yet even on the drawing board, at least as far as I knew, such a threat did not make me fear for my life, but the unrelenting emotional artillery vented in some attempt to impress me with the seriousness of my failure and the supposed gravity of the situation had its intended effect.

I got back to work. The rest of the staff just began theirs. At our first post-deadline staff meeting, Joyce and Bob hammered into me that everything would have to be re-written by a committee that was in practice to consist of the two of them. Over the course of the next several weeks they not only corrected but re-wrote much of what I’d submitted in a way that seemed to me verbose, cliché ridden, often simply obtuse. The editorial I’d painstakingly drafted was disemboweled and in the process turned into something vacuous. In most cases, I ended up rewriting their rewrites, and that process might have continued forever had we not been faced with another deadline, one I didn’t dare circumvent. But this time, however, in spite of multiple all-night meetings, laboring over the layout of our first edition, we managed to come up with something that represented a sort of lowest common denominator symptomized by the entrance of Mother Marceline LeTourneau.

This other Marceline, a very small town grand dame and former Pentecostal evangelist who had been following Jim, at least from a safe distance, since he was a very young man selling monkeys door-to-door, had only months earlier moved triumphantly from a comfortable existence in Indiana into senior housing she’d endowed on the palace grounds in Redwood Valley. She was believed to be possessed of deep pockets as a result of which Jim gave me specific instructions to accept whatever she might submit, however Bible-belting and shrill, with minimal editorial interference. I did my best to oblige, despite what seemed her offensive self-righteousness combined with sheer babbling idiocy that alienated the entire staff and must have devastated Edith Roller who found herself suddenly displaced by everything she despised. This square seventyish dowager demanded a regular column and got it with a “Yes, Ma’am.” I will never forget the, plump, pontifical, very white LeTourneau, adorned by a mountain of very well organized white hair, jumping up and down on the stage before each public meeting, screeching testimony that challenged the eardrums not to mention common sense. And then there was her handwriting which was infuriatingly easy to read. Reviewing what she did largely write herself now, I find in it a surprising sincerity that I miss in many of the other articles that came from the head – only in the sense that they were calculating – and not at all like hers, apparently from the heart. Jim presciently noted to me at the time that she was one of the few fundamentalists, following him, who at least knew how to write at all. Jim Pugh might have been added to that small number. In any case, she got what was coming to her in the first edition: not the second page editorial she might have longed for, but a place towards the end of a long line of testimonies which I have to say even now were all to my knowledge essentially truthful, though they might seem to the uninitiated a babble of very foreign tongues.

A longer word about the testimonial accounts with their melodramatic titles which comprise the bulk of the first and subsequent issues. Exaggerate and even distort though we might through successively ridiculous rewrites, the testimonies we included were ones about which we felt confident, though we had written them ourselves, based on interviews with individuals who were only too willing to substantiate their claims: Rev. Harry Williams, Polla Mattarras, Helen Torkelson, Elretha Grays, Mark Cordell, Chris Lewis, Liz Forman. Except for Liz, they’re all deceased now. Healed, one might say, so they might die soon enough for the most part in the wilds of Guyana.

Press delays postponed publication for several more weeks after Jim gave his thumbs up to the entirely re-configured first edition. Volume 1, No. 1 of our “apostolic monthly” began to be mailed out shortly after the Summer Solstice. While Jim and Council members warmly congratulated all of the staff and me in particular, I felt acutely embarrassed and didn’t want anybody I respected in the outside world to which I would soon be returning ever to set eyes on it. Even now, re-reading “Brotherhood is Our Religion,” the editorial that bears my name, I’m struck by the subjective fact that there’s nothing there – not even wind blowing through leafless trees.

The one mildly redeeming quality of the first edition shows its face meekly in the last unsigned article, “Thy Will Be Done,” telling of the practical ongoing good works of Peoples Temple. The unspectacular placement no doubt reflected the anticipated lack of interest in good works for their own sake. Even here, though, disappointment walked in the form of bald lies we were obliged to tell. The Redwood Valley Temple was never – as paragraph three alleges – a “community center” open “to any school, church, public or private agency or organization that has need of such facilities.” Nor was this “beautiful edifice” a place for “recreation.” I don’t remember the swimming classes for children, though there was certainly a largely underutilized indoor heated pool, dramatically available for mass rebaptisms in the name of “I God Socialism.” And where was the homework help, the music lessons or the art program that the article alleges? “The other beautiful senior residences, some in the neighboring community of Ukiah” were largely care facilities on which PT operators were making a profit, often with taxpayer largesse.

None of the articles among the pack aimed to encourage any critical thinking whatsoever. Writing such garbage over a long period could turn even a good writer into a mindless hack or even worse, one who comes to believe that the only real authority is the ability to manipulate others for one’s own naturally altruistic ends. Even at the time I felt profoundly uncomfortable letting myself to be used to deceive. I just felt that God must know what He was doing because He alone by definition could harbor no merely selfish motives.

By the time the first edition did appear, the magazine’s staff was hard at work on the next, which we hoped to have ready by August 1st on the front-cover advertised expectation that The Living Word would be issued monthly. The atmosphere among us had changed and all for the better. The rift between Joyce and me, exacerbated by Bob’s mistrust of my eccentric and often erratic ways, had really begun to heal. All of us seemed to be learning to work together in a fairly relaxed fashion as a real socialist team, joking and teasing rather than insinuating or threatening. I figured that if Edith could retain her equanimity in the face of being jilted by God in favor of blubbery Mother LeTourneau, I could accept challenges to my own literary and overall intellectual self-infatuation. Though our staff meetings continued to last long into the night, I no longer feared them, but rather looked forward to the comradeship and sense of shared mission.

To be sure, Peter Wotherspoon shared in no sense of relaxation or even – like Edith – in a stoic acceptance of fate. On a Wednesday night shortly before publication of that first edition, Jim entered the sanctuary of the Redwood Valley Church particularly early and without any musical build-up in what can only be described as a dreadful mood, prelude to some storm. As soon as he had taken his place behind the pulpit, eyes darkly shaded, he called out for Peter in a low but ominous voice. It was no help to Peter that he had to be summoned from a rest home in Ukiah where he had been elder-sitting so that others could be present for the catharses. It was never good to keep our god waiting. Long before Peter’s ass was “front and center,” guarded by Jack Beam and a few other well meaning thugs, we all knew or thought we knew what the nature of Peter’s transgression had been. He stood accused of child molestation, specifically of inducing a twelve-year-old boy, Mark Cordell – whose testimony, “God’s Prophet Ran to Me,” re-written entirely by us, of course, could soon be read in the first edition of our magazine – to suck him off in the parking lot of Benjamin Franklin Jr High in Frisco while most of the rest of us had been inside making converts and raising money. Ironically, Mark’s testimony was the only testimony of a child we had included, and the photo that accompanied it still reveals an attractive and quite androgynous young man at the edge of puberty. There were the predictable shouts of outrage from most of us. If it had been left to the congregation, Peter might very well have been crucified in the parking lot that night. Fortunately, our prophet and only God, who leaped off the platform at the sight of Peter, apparently insensate with rage, attempted to rescue Peter from us and from himself by offering him too an opportunity to shape up and fly right. If there were a “next time,” he promised to turn Peter over to the secular arm of law enforcement so that he could really learn his lesson by getting gang-raped in jail.

The new danger to the rest of us came not unexpectedly from Council, which quickly demonstrated how uncomfortable it was with the newfound solidarity of the staff, perhaps – and here I can only speculate – reflecting the good cop’s private instructions. In any case, the matter of anarchism seemed very much on God’s mind. At the Wednesday night meeting following the appearance of the first issue, Jim again lashed out against “anarchists” in our ranks who in his opinion posed a greater danger than “bourgeois fascists” because they pretended to be our friends but actually comprised “a fifth column.” He described “anarchists” as intellectuals who thought they knew better than everyone else and invited members of all educational backgrounds to look around the room. “You all know who I’m talking about. Is there anyone who needs help recognizing an anarchist?” That the particular “anarchists” in question happened to be students in the PT dorms in Santa Rosa who were called “front and center” to answer for their alleged sins relieved me only slightly and may have caused the likes of Joyce, Bob and Peter lumps in the throat as well. All of us knew that any of us could be next if we failed to please. In any case, Joyce and I had already compared notes. She knew as well I did that Council, perhaps on Jim’s instructions, was intent on breaking up our circle and certainly changing all of our individual behaviors that deviated far too much from the accepted “socialist” norm.

The Monday night sessions I experienced as a “probationary” counselor became even more challenging than before. I could pretty much guess how rough the session would be by how solicitous the counselors were upon my arrival. Refreshments offered as if they might constitute my last meal certainly didn’t put me at any ease. Even though Larry Layton had been removed by Jim as head of Council, possibly for premature Stalinist behavior, he behaved like a pit pull just barely leashed. The ones who smiled through it all were the worst, however. I shall refrain from mentioning names, because a number are still living and might not like searchlights. Since they couldn’t pummel me regarding my performance on the paper, they briefly changed tactics and focused on my failure to find a job. A deadline of one week was set and reset several times until all sides absolutely lost patience and I stood accused of betraying the cause by my manifest contempt for an 8 to 5 job, a charge of which I was sadly guilty.

The deadline for the second issue arrived the weekend of July 9th and 10th, a new moon in Cancer, which found most of the staff, myself included, in Los Angeles, having spent the night awake in Bob Houston’s car, reading and revising our copy, nerves shot on caffeine, while we took turns driving 500 miles south. This time fortunately there had been little need to debate and virtually no dissent. Bonnie Beck had picked up the semi-final draft the previous Sunday and passed it on to Jim, who had as yet made no comment.

At 10 the following morning Joyce and I had a private audience with Jim in a side balcony of the almost-empty Embassy Auditorium where he was scheduled to speak in several hours. Before reviewing our semi-final version, contained in separate manila folders, God took off his dark glasses. The eyes which I watched from the side seemed quite prudent but were in no way bloodshot. Perhaps he’d experienced a good night’s sleep in the back of Bus #7, the PT equivalent of the president’s Air Force One jet. He skimmed through each proposed article but said little except to suggest one easily manageable addition.

Joyce and I, who in practice now served as co-editors, proceeded to broach our one significant disagreement, regarding the article penned by her beau on the subject of reincarnation which we’d not found any way to cover in our much-harassed first issue. As it stood, I told Jim, the proposed article was almost incomprehensible and made a difficult topic seem absolutely impossible to grasp. Not unreasonably, Joyce wanted me to rewrite the whole thing, whereas I preferred an altogether fresh take that I’d already finished. Not wanting to take sides, God temporized but did agree that something good about reincarnation needed to be included without further delay. The Law of Karma served as the basis for His whole metaphysical embrace, and we needed to prepare our constituency for its relevance to their lives. We departed in the radiance of His praise and assurance that we would succeed in producing just what “the Cause” needed.

Surrounded by busy friends and colleagues, I spent the rest of that happy day negotiating a worthy compromise around a solid oak table at the home of Liz Forman’s grandparents where the whole staff had camped out. At one point, I remember thinking: how I feel now is what heaven must feel like all the time. And I remember thanking Jim silently for being alive and walking the part of the earth where I hung out and found myself in such desperate need of salvation. It was just about the last happy moment I recall.

As Bob was needed to drive a bus back to Ukiah and be available Monday morning to teach, he asked me fraternally to drive his old car, awaiting the completion of work, back to Ukiah the next morning. Not having a paying job which required my services, I gladly accepted the opportunity for a little unanticipated freedom.

The consequence at the Monday night Council meeting was what I had feared but not exactly expected. “Why did you take so long to get back? Why weren’t you here ready to look for work this morning?” screamed one counselor who entertained a particular distaste for me. Another threatened unspecified but severe punishment. While their attacks were still building momentum, the staff of the magazine arrived for a consultation about our progress of which I hadn’t even been apprised. They were asked to wait their turn in an adjoining bedroom, where they were able to hear everything and get a general idea of the attitude that they as good comrades were expected to demonstrate towards me. This particular humiliation stoked my anger, but wisely I kept a tight lid on it.

It said everything for the bonds of trust that were developing as a result of our teamwork – not to mention considerable personal courage – that staff members uniformly stood behind me when questioned about signs of my continuing “unsocialist” behavior. Disregarding the expectation that they would provide evidence for the prosecution, Joyce opined with more than a little sensitivity that I was definitely learning to work with others and that, in any case, socialist behavior was something all of us were still learning and that she herself proved no exception. Bob enthusiastically assured our inquisitors that the next issue would be something about which all of us could feel proud and congratulated me on my ability to grow from criticism. But all of us had met our match in the glacial unity of this Council whose only soft spot seemed to rest beneath the breast of Karen Layton, who was absent that particular night. Clearly irritated by the solidarity of the staff in my defense, the Secretary of the Council jumped to her feet and accused the whole staff of standing up for me to “protect your anarchist asses.” She intelligently refrained from threatening: “I’ll see you all on the floor Wednesday night.”

Leaving this session in a mood of defiance, I, for one, had decidedly reached the limit of my tolerance but somehow retained hope that our God would stand behind my resistance to unjust demands. And so, disguised as a letter to the Secretary of the Council, I wrote a petition of grievances intended for the eyes of Jim Jones. This I delivered to Carol Stahl, standing at the foot of God’s podium after the following Wednesday night catharsis meetings to accept messages in writing. While waiting for him to get to mine, I circulated through the crowd of counselors standing back by the pool, watching the proceedings, and gave a copy to each so they could follow whatever His response might be.

When he had finished reading, he announced over the audio system to the crowd that was still milling about the various concessions stands or were gathered, as most of the counselors were, in small groups, something like this:

“What I’m reading here forces us all to pause and think. I must say I’m grateful to the comrade whom I shan’t mention, who brought this information to me. This is a socialist family, a society of equals, the only one you’ll ever know. Counselors and others I appoint must never abuse their authority. Am I understood?”

His voice was unusually mild for a rebuke; he smiled at me broadly as his eyes panned the sanctuary. Everybody seemed to stop what they were doing. Nobody said a word.

“Members of this socialist family must always feel free to bring their complaints directly to me. Your God cares. Those I delegate power to must never act as if they are more than equals. The truth is that they have just taken on more responsibility and will remain therefore more accountable than the rest of you, at least for now. Those guilty of abuses will be removed and taught a lesson. Don’t anybody get ideas of grandeur. This is only kindergarten.”

He smiled at me broadly as he finished, too. The very mildness, however, seemed to convey a double message: the spoken one which relieved me for the moment, the unspoken one that assured counselors he wasn’t altogether serious. Nevertheless, I had been publicly exonerated, an outcome that was exceedingly rare when the adversary was the Council which – according to myth Jim had propagated – knew his mind and, in any event, acted upon his orders. After he’d moved on to other more private conversations, a number of counselors approached and went through the motions of apology. Karen Layton alone thanked me with a sincerity that was incontrovertible for performing a service to everyone. Perhaps Jim’s reasoning was very simple. If he didn’t give me the bare support I needed, I’d simply leave and in so doing bring down the precarious edifice that was The Living Word. Possessed of paranormal functions that were still very much in evidence, he might very well have wanted me to stick around and help PT respond to the first serious journalistic attacks since it had arrived on the West Coast seven years before, the attacks that were about to be generated from the poison pen of Lester Kinsolving, writing in the Hearst flagship, The San Francisco Examiner.

I attended one more staff meeting of The Living Word. It took place on a warm but strangely cloudy Saturday afternoon at the home that Patti Chastain shared with several others. Conversation was lively and good natured. The final copy of the second issue would be going into production within a week. We talked vaguely about future plans, but nobody felt the need to work terribly hard, and so we hung out and – though we would have denied doing so at the time – partied. Patti showed us some of the art work she was preparing. It was full of light; she reflected an optimism I wanted to share too. Everyone seemed to have a bottle of Dr. Pepper in hand and no troubles close by.

At the end of the following week, without confessing to anyone except Liz Forman, who found me one afternoon in bed with my childhood lover, I was gone to follow another mirage into a desert. Regardless of God’s assurances, I was simply tired of trying so hard to be a good socialist. The odds against somebody like me transforming my life were simply too great. I wanted to go back to Babylon and have what I wanted to believe would be healthy fun.

The Living Word stumbled or bumbled through several more issues. But I wasn’t present to see it unceremoniously buried and almost forgotten. Thanks to Laura Kohl for raising it, this capsule of a moment in time and a mostly sorry but instructive place, from the dead.

(Garrett Lambrev is a retired librarian, who continues to work part-time, a poet by nature and a student of history. He lives in Oaktown, California, with his cat and books by the side of a deep ravine. His complete collection of writings for the jonestown report is here. He can be reached at garrett1926@comcast.net.)