My younger sister Ann Elizabeth Moore apparently was the last to die in Jonestown. While others found in Jim Jones’ cabin died of poison, including my older sister Carolyn Moore Layton, Annie died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. She left a suicide note that filled several pages extolling the virtues of Jim Jones and praising the beauties of Jonestown. “What a beautiful place this was,” she wrote, noting the care for the children and the seniors. The last line – “We died because you would not let us live in peace” – appears in a different color ink over her signature, “Annie Moore.”

My younger sister Ann Elizabeth Moore apparently was the last to die in Jonestown. While others found in Jim Jones’ cabin died of poison, including my older sister Carolyn Moore Layton, Annie died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. She left a suicide note that filled several pages extolling the virtues of Jim Jones and praising the beauties of Jonestown. “What a beautiful place this was,” she wrote, noting the care for the children and the seniors. The last line – “We died because you would not let us live in peace” – appears in a different color ink over her signature, “Annie Moore.”

We did not know that Annie was one of only two persons to die of gunshot wounds in Jonestown, nor of her last letter to the world, for several weeks. The news following the assassination of Congressman Ryan and four others at the Port Kaituma airstrip, and then the stories of the mass deaths in Jonestown, trickled out very slowly. My parents initially expressed hope that my sisters were alive. When they learned that Sharon Amos killed her children and herself in a bathroom at the Temple’s headquarters in Georgetown, however, they realized all the others must also be dead. The news that Jim Jones was dead confirmed what I’d believed from the start: Carolyn and Annie were among the dead because they were true believers. As I wrote in my journal the first week after November 18 – and reproduced in A Sympathetic History of Jonestown (1985) – I suspected they might have had a larger role in the deaths:

The thought of my sisters killing children made me physically sick. The thought of them helping other people, or forcing them, to take poison, was hateful. I couldn’t believe that they could do such a thing. But if they had? I hoped they were dead as well.

When my family gathered on Thanksgiving Day, five days after the deaths, we still didn’t have any definitive word. My mother, Barbara Moore, said the only thing she was worried about was Carolyn and Annie’s re-entry into society after all that had happened. I said I didn’t think she needed to worry about that right then. The following Monday, November 27, we read that Annie had been shot. Later that day we received official confirmation from the State Department that Carolyn and Annie were dead. Carolyn’s son Jim Jon (Kimo) was never identified.

The news that Annie was shot was liberating in some respects. “Maybe Annie knew,” I wrote in my journal. “Maybe she was trying to escape. Maybe she didn’t poison people. Maybe she refused. So she was shot.” We wanted to believe that at least one of my sisters had resisted. This was not the case.

Odell Rhodes, an eyewitness, stated that Judy Ijames and Annie Moore brought the vat of poison to the stage in the pavilion (Awake in a Nightmare, 1981).Another eyewitness, Stanley Clayton, said that Annie used force to inject the unwilling with poison (The Children of Jonestown, 1981). But a third eyewitness, Tim Carter, reported that he saw Annie in Jim Jones’ cabin, with a number of other Temple leaders who were making last minute arrangements, as the deaths were occurring (Unpublished notes, February 1979). This would mean she was nowhere near the pavilion.

Nevertheless, Annie can be portrayed as one of the villains in the Jonestown story. She was Jones’ personal nurse, administering various uppers and downers to him so that he could function. She worked in the community’s bond, that is, the storehouse of drugs. She also wrote a memo to Jones suggesting various ways to kill people in a last stand:

I never thought people would line up to be killed but actually think a select group would have to kill the majority of the people secretly, without the people knowing it. The way I don’t know. Poisoning food or water supply I heard of. Exhaust fumes in a closed area (carbon monoxide) I heard was effective while people are asleep. It would be terrorizing for some people if we were to have them all in a group and start chopping heads off or whatever. This is why it would have to be secretly.

The context for the note was Annie’s justification for committing revolutionary suicide, rather than to hold out fighting. She attempted to make the case for planning their deaths, rather than leaving anything to chance. “I think life is a fuck-over anyhow whatever we do, but maybe less with the revolutionary suicide so I stick to it,” she closed. “I’ll do whatever is expected of me, no matter what you have me do.”

* * * * *

Annie joined Peoples Temple in 1972, shortly after graduating from high school. She was convinced of Jim Jones’ miraculous healing powers, including his ability to raise the dead. She was even more persuaded of the rightness of the cause: “There is the largest group of people I have ever seen who are concerned about the world and are fighting for truth and justice” (The Jonestown Letters, 1986). She considered Peoples Temple the only place where she saw “real true Christianity being practiced.” Her letters to us described her daily activities (like living in a “dorm” with six other female students who slept in bunk beds in the garage, and had study carrels in the house), and her commitment to changing the world rather than getting married (“anyway the dudes around here are real creepy”). In a letter dated March 30, 1973, she wrote: “I want to be in on changing the world to be a better place, and I would give my life for it.”

She seemed to believe that Jim Jones made all their good work possible. As his personal nurse in Jonestown, she was always nearby. John Jacobs, co-author of Raven (1982) with Tim Reiterman, discovered an undated note that Annie had written to Jones in which she apologized for being abrupt with him.

I just wanted for you to know that I do not mind being your nurse and there is nothing more I would rather be. You should not feel guilty for having me watch you. I would rather be around you than anyone else in the world.

From her earliest correspondence to her final letter to the world, Annie praised Jones.

I want you who read this to know Jim was the most honest, loving, caring, concerned person whom I ever met and knew… His love for humans was insurmountable… His hatred of racism, sexism, elitism, and mainly classism, is what prompted him to make a new world for the people—a paradise in the jungle.

* * * * *

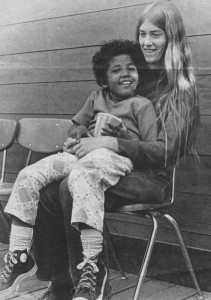

How did Anna Banana—the comedian, prankster, artist, musician—come to decide that killing the children would be saving them, in word if not in deed? It is a question without an answer. Annie seemed to remain her effervescent self, at least in letters she sent to us. She was always herself: at home in community college, in the hospitals where she worked in Ukiah and San Francisco, and in the Jonestown clinic. A former Temple member who had roomed with her in the Santa Rosa dorm told us that, “Annie was one of the few whites who wasn’t afraid of black people.” She made people laugh.

Another former member recently sent us a note Annie had slipped to her as she left Jonestown a week before the end. I reprint it in full:

Whatever comes, comes, so goodbye. I know you are a true and loyal comrade and I’ll always know it. I wish you could be here longer. It has been very rough lately for us all but we’ll all keep pushing. I’ll come say hi to you on the radio more. I am sorry you have to go but I know you will do the best job. Jim loves you very much. From Annie.

On the reverse side she’d written, “I hate goodbyes.”

There is no answer, there is no explanation. Brainwashing assumptions and psychoanalytical theories fail to do justice to the existential issues posed by the life and death of Annie Moore. Polarities of good and evil are inextricably intertwined in her life.

Yet we continue to love her. “I miss Annie still, and so many others, as we all do,” wrote the friend to whom she gave her goodbyes. Yes, we miss Annie still.

(Rebecca Moore is a professor of Religious Studies at San Diego State University. She has written and published extensively on Peoples Temple and Jonestown, including her most recent book Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple (Praeger, 2009), and an extensive description on the Temple appears at the World Religions & Spirituality Project at Virginia Commonwealth University.

(Rebecca is also the co-manager of this website. Her complete collection of writings which appear on this site are collected here.)