(This article is superseded by a 2017 update.)

(This page is adapted from the article, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony Pinn and Mary Sawyer (Bloomington: Indiana Press University, 2004), 57-80.

The Peoples Temple agricultural project in Jonestown, Guyana, was a racially black community in a number of key respects. A large group of African Americans who migrated from the southern U.S. to California made up a sizeable contingent of those living in Guyana. African Americans had long supported the Temple with contributions, tithes and wages while living in California, but in Jonestown it was clear that the Social Security checks of black senior citizens made up the primary source of income for almost a year. Finally, the majority of Jonestown’s residents were black, and African Americans held key leadership positions in the jungle outpost.

This article expands upon previous demographic studies of Jonestown which documented the fact that the project had a predominantly black membership. We attempt to further the discussion of Peoples Temple by considering that black membership with additional data unavailable to previous studies. In addition, we look at elements of the Temple’s religious culture within the context of black religious experience. This framework helps to illuminate and clarify practices within the movement.

Sources

Our starting point was a roster of those who died which was published by the U.S. Department of State on 17 December 1978.[i] This document served as the basis for the list of the people who died in Jonestown which appears on this website.[ii] The initial list has grown and been corrected and amended by family members who pointed out errors to the website manager. The accuracy and completeness of the cohort of Temple residents of Guyana jumped tremendously with the release of papers from the FBI in 2002 pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, McGehee et al. v. U.S. Department of Justice. Additional sources include reports and censuses generated by Peoples Temple, such as a listing of people planning to go to Guyana, and monthly head-counts of people living in Jonestown.[iii] A collection of passport and other photographs of Temple members at the California Historical Society helped with some identifications when there was a question of race or gender, but this method was not foolproof. Finally, the assistance of former Temple members, including Laura Johnston Kohl, Grace Stoen Jones, and Stephan Jones, greatly helped in the identification of family members, names, and so on.

The Findings

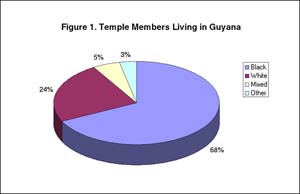

We began with a larger cohort than previous studies: namely, all Temple members living in Guyana rather than just those who died in Jonestown. Nevertheless, the number of African Americans comprising the group tops two-thirds, at 68% (Figure 1). Black membership thus dominates Temple life in Guyana by a substantial majority, but by a slightly smaller margin (2%) from earlier studies. While it seems likely that the percentage of black members to total membership in California is greater than either 68% or 70%, this conclusion is anecdotal, and based on the observation of hundreds of photographs of stateside members of Peoples Temple.[iv]

We calculate that approximately 1020 members of Peoples Temple were living in Guyana as of 18 November 1978. We have identified 122 people who survived the tragedy, but this figure is rather fluid.[v] The news media frequently reported that 918 people died in Jonestown. This number includes four non-members and one member who were killed at the Port Kaituma airstrip outside Jonestown, and four members who died in Georgetown. We have come up with names of 900 individuals who we are fairly certain died, though many of these are children, never identified, who we presumed died because the custodial parent also died in Jonestown. Despite the shortfall, we do not dispute the official figures, but rather have tried to give names to as many people as we possibly can.

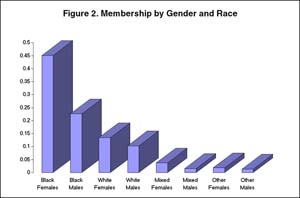

Almost twice as many females as males lived in Jonestown, which becomes significant when we look at leadership patterns in the community (below). Black females made up the largest group of residents of Jonestown (45%), with white females comprising 13%. Black males made up over one-fifth (23%), with white males making up a tenth, and the remainder falling in the Mixed or Other categories (Figure 2). Clearly women played an important role in the community, both numerically and organizationally.

The geographical distribution of where people were born indicates a strong southern black presence, as Hall observed. The U.S. map (Figure 3) indicates from which states ten or more members of Peoples Temple originated. California, of course, is the largest as the Temple’s base of operations (374), with Indiana coming third (61), as its place of origin. But the chart shows that 345 came from nine southern or border states, with 93% of these members being African American.

Figure 3 Map. (pdf)

| Table 1. States of Origin (more than 10 Members) | ||||||

| Blacks | Whites | Mixed | Other | Total | ||

| California | 232 | 106 | 29 | 7 | 374 | |

| South | ||||||

| Texas | 113 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 122 | |

| Louisiana | 53 | 1 | 54 | |||

| Mississippi | 48 | 1 | 49 | |||

| Arkansas | 39 | 2 | 41 | |||

| Oklahoma | 19 | 2 | 1 | 22 | ||

| Alabama | 19 | 1 | 20 | |||

| Missouri | 10 | 3 | 1 | 14 | ||

| Georgia | 9 | 3 | 12 | |||

| Tennessee | 11 | 11 | ||||

| Total | 345 | |||||

| Others | ||||||

| Indiana | 23 | 36 | 1 | 1 | 61 | |

| Ohio | 2 | 15 | 17 | |||

| Illinois | 12 | 2 | 2 | 16 | ||

| Washington | 5 | 9 | 14 | |||

| New York | 4 | 7 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Total | 120 | |||||

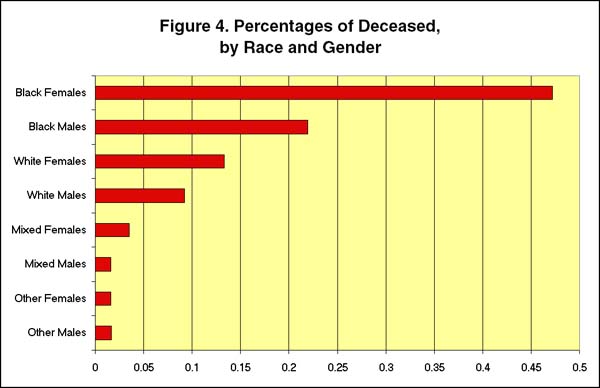

Many of these African Americans died on 18 November 1978. The proportion of blacks who died (69%) does not differ significantly from the proportion who lived in Guyana (68%). Figure 4 shows that almost half of those who died in Jonestown were black females (47%), corresponding to their presence in the community (45%), while black males also died at the same proportion as their presence (22%).

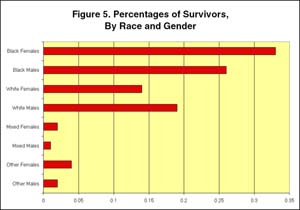

The gender-race distribution shifts when we consider who survived the tragedy by either being in Georgetown, the capital, or by leaving Jonestown on 18 November (Figure 5). Only one-third of the 122 survivors were black females. About one-quarter of the survivors were black males, several of whom were members of the community’s basketball team, in Georgetown that day for a championship basketball game. In fact, almost a tenth (9%) of the male survivors belonged to the basketball team. Fourteen percent (14%) of the survivors were white females, but the percentage of white male survivors surpasses their presence in the community (19% as opposed to 10% overall). Only 30 children under the age of 19 survived, with that figure dropping to 14 survivors under age 10.

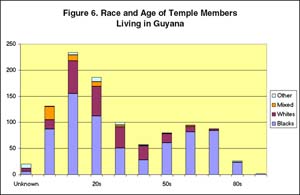

The numbers show two age bumps for those living in Guyana: namely a large number of children under twenty, as well as those in their twenties; and a secondary group of senior citizens (Figure 6). One hundred thirty-one children were under the age of ten; 234 were between the ages of 10 and 19; and 186 were in their 20s. This means that more than one-half of the residents were under thirty, and more than one-third were under twenty. While many teenagers worked in Jonestown to support the project, these figures nevertheless reveal a relatively large non-productive population. Two hundred eleven (211) people were sixty and older, with three-fourths of this segment being black females.

While the number of seniors may indicate a sizable non-productive work force in the community, they nevertheless played an important role in supporting Jonestown through their monthly Social Security checks. We took a snapshot of Social Security income for the month of September 1978, since we had the greatest amount of information for that month.[vi] Because there was public concern about Social Security fraud, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare provided a list of the beneficiaries and the checks which had been recovered from Jonestown. In that month 173 beneficiaries received a total of $36,548.30 in checks which were recovered — uncashed — at the site of the tragedy.[vii] Of those 173 beneficiaries, 157 were black, 15 were white, and 1 was Native American. But if we add to that figure those who had received Social Security income in other months, the number of blacks jumps to 182, the number of whites to 18, with a single Native American recipient, and a single Latino (Table 2). Thus, African Americans, particularly the elderly, were helping to finance the community in Guyana.

| Table 2. Social Security Recipients Living in Guyana | |||||

| Black | White | Native American | Latino | Total | |

| Sept. Check | 157 | 15 | 1 | 173 | |

| Add’l SSA | 25 | 3 | 1 | 29 | |

| Total | 182 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 202 |

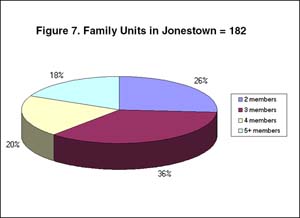

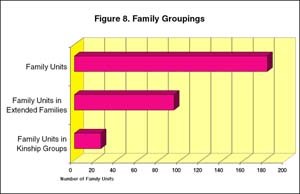

We also looked at family groupings in Jonestown and discovered a large number of affective ties. Only 256 people who died in Jonestown had no apparent family connections with anyone else present, or 20% of the total. Within the 80% remaining, we identified 182 family units, with a family unit being defined as at least one parent and at least one child.[viii] Three-quarters of these family units consisted of three or more members (Figure 7). One hundred family units combined to make up 43 extended families, which we grouped by blood ties or by adoption, e.g. grandparents, parents, children; aunts, uncles, cousins (Figure 8). This means that about half of the 182 family units which existed in Jonestown had additional family ties with each other.

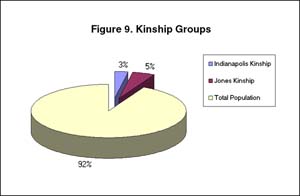

We found further connections between family units and extended families in the form of kinship groups, which linked extended families through marriage. We identified two main kinship groups in Jonestown, which we called the Indianapolis group and the Jones group. These two groups accounted for six extended families, 25 family units and 84 individuals; that is, they encompass eight percent (8%) of the total population in Guyana (Figure 9). When we look more closely, we see that the Jones kinship group alone makes up five percent of the total. This means that Jim Jones not only acted as the group’s leader, but was also intimately connected to a large number of residents. Clearly he had as much family investment as did the other individuals living in Jonestown.

Members of Peoples Temple came from a variety of jobs and professions. The majority, however, came from the working classes, as Table 3 indicates.[ix] This table indicates professions people held before moving to Jonestown.[x] In light of these figures, it does not seem accurate to assert, as C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya do, that most black members of Peoples Temple were “impoverished and de classé.”[xi] Although whites are disproportionately represented in the fields of Education and Law, blacks clearly dominate all of the professions listed, in keeping with the Temple’s racial profile.

| Table 3. Professions of Peoples Temple Members | |||||

| Occupation | Black | White | Mixed | Other | Total |

| Medical |

104

|

45

|

5

|

1

|

155

|

| Clerical (secretaries, clerks, tellers, s |

60

|

34

|

4

|

4

|

102

|

| Food/Cooks/Wait Staff |

90

|

9

|

3

|

2

|

104

|

| Farm/Agricultural |

65

|

9

|

1

|

2

|

77

|

| Domestics/Housekeeping |

73

|

1

|

2

|

76

|

|

| Building Trades (Elect., Plumb., Con |

27

|

16

|

43

|

||

| Mechanics |

24

|

14

|

1

|

2

|

41

|

| Education |

20

|

19

|

2

|

1

|

42

|

| Custodian/Maintenance/Laborer |

28

|

11

|

3

|

42

|

|

| Finance (Accounting, Bookkeeping) |

6

|

14

|

1

|

21

|

|

| Management (Store, Office, Care H |

11

|

7

|

1

|

19

|

|

| Law |

1

|

3

|

4

|

||

Jobs and responsibilities shifted at the agricultural project, with many more people working in agriculture, food preparation, and mechanical and building trades in order to support the community. Some people moved up in terms of responsibilities, especially in terms of managing agricultural production. Some moved laterally, shifting from cooking or domestic work in the United States, to similar occupations in Jonestown. Some moved down the social ladder, exchanging professional responsibilities for manual labor.

When we turn to leadership roles in Jonestown we get some evidence of racism, as noted by others.[xii] The Planning Commission (PC) was Jim Jones’ personal advisory group, his closest associates and decision-makers. Only 6 of the 37 members of the PC were black, or one-sixth.[xiii] While this figure seems low, it may indicate class or occupational differences in which blacks have been historically under-represented. It is certainly greater than the one-tenth percentage benchmark commonly used to assess black progress in U.S. society, even though it is well under one-tenth for the population in Jonestown.[xiv] If we look at the individual names on the list, we see that fifteen PC members came from Indiana, and thus were some of the institution’s longest and most devoted followers. Almost twice as many women as men (25 to 12) made up the PC, with five of those men coming from Indianapolis. The high proportion of females indicates Jones’ preference for, and trust in, women over and against men. At least a half dozen women on the list were those with whom Jones had had sexual relations.

The PC seemed to wield enormous power as long as Peoples Temple was based in California. Upon the move to Guyana, however, authority seemed to decentralize among a larger, more diverse body, as an organizational chart recovered from Jonestown reveals (Figure 10). Fifteen department heads or their assistants were white, while 24 heads or assistants were black, with the remaining three being Native American, Latina, and unknown. African Americans headed six departments — Public Utilities, Production, Businesses, Education and Child Care, Entertainment and Public Relations, and the “Administrative Triumvarite [Triumvirate]” — and served as assistants in all other committees except for Legal and Accounting (note: the Legal Department was composed of three lawyers). The two staff members of the triumvirate were black. As with the Planning Commission more females appear on the chart than do males.

Figure 10. (pdf)

Notes to Figure 10:1No such person; probably Gene Chaikin

2No such person; probably Harold Cordell

3No such person; probably Phyllis Chaikin

4No such person; probably Shirley Hicks

As egalitarian as this organizational chart appears, the reality was that power and authority in Jonestown rested in the Planning Commission and remained with Jim Jones rather than in a decentralized leadership system. Although a piece of paper affixed to the chart is dated 12 July 1978, we do not know the exact date the chart was prepared. It seems likely that it was fabricated for the benefit of Congressman Leo Ryan’s trip to Jonestown in November.[xv] The organizational chart reveals a number of errors and omissions, such as listing one of the lawyers as Gene Wagner rather than Gene Chaikin. There are other problems with the chart.[xvi] For example, the security team is not identified; responsibility for the work crew — those in charge of community discipline — is not listed. What can be said, however, is that the chart correctly identifies a number of black leaders in Jonestown, though it may not accurately represent the level of authority they actually had.

Matching Jonestown’s racial profile more closely was the project’s Security Team. It is important to note here that this is the most anecdotal compilation of names used in this study, as well as the most sensational. These names were provided by survivors returning from Guyana — including defectors and apostates as well as loyalists in the first stages of grief — who were questioned by the FBI upon their arrival in the United States.[xvii] In other words, traumatized individuals at their most vulnerable either volunteered or were coerced into naming names. Of the 67 people named as security, 58% were black, while 39% were white. Only five females were identified as being part of Security. We believe that security figures are somewhat inflated, since some informants identified all members of the basketball team and the archery team as part of security.

Analysis and Implications

These figures show that Peoples Temple’s agricultural project in Jonestown, Guyana, can appropriately be identified as a primarily black community in racial terms for a number of reasons. First, the majority of Temple members and Jonestown residents were black. The numbers alone do not necessarily indicate the cultural blackness of an institution in terms of its values, goals, and purposes. But the high percentages of black involvement in the Temple’s Guyana operations do point to its existence as a racially black group.

Second, the Southern origins of Peoples Temple members also reveal the black roots of the organization. Several authors have noted that Southern blacks who moved North or West looking for work and safety during the migrations of the 1930s and World War II found established black churches too “fine, fashionable and formal,” and thus turned to black “cults.”[xviii] Joseph Washington wrote that these black religions provided “a creative, imaginative and indigenous (if insufficient) response to the failure of churches and society to satisfy the immediate needs of black people.”[xix] We can see that the experiences of Southern black members of Peoples Temple may well have paralleled those who joined Washington’s black “cults.” The involvement of Southern blacks in the movement strongly suggests a black racial and cultural identity.

Third, elderly African Americans provided many of the day-to-day financial resources for the project by donating their Social Security income. In return they received health care, housing, food, and other basic necessities. Although one surviving black senior citizen, Hyacinth Thrash, describes an inadequate diet in Jonestown, she does add that:

One thing you can say for Jim — he didn’t deny medical care when they needed it…. We all had our blood pressure checked regular, Indians too…. Jim had real fine caring nurses too, both black and white.[xx]

Many seniors had signed life-care agreements with non-profit corporations created by Peoples Temple in exchange for their Social Security income, much as senior citizens sign up for life-care with centers in the United States. Their financial contributions were crucial to the maintenance of Jonestown, and the fact that September Social Security checks had not been cashed as of 18 November may point to the existence of a suicide plan as early as September if not before.

Finally, although African Americans comprised only a minority of Jones’ personal leadership group, they did make up the majority of department heads and assistants in Jonestown. They also dominated the Jonestown Security Force, a contradictory position in which blacks may have been both feared and hated, as well as trusted and responsible. Nevertheless, it is clear that African Americans played a number of significant leadership roles in the Jonestown community.

If we look at Peoples Temple within the normativity of black experience rather than white, we then understand that the move to Guyana — far from being aberrant or indicating isolationist tendencies in traditional New Religious Movements of the period — reflects the exodus to the Promised Land which has characterized black religion in America. Charles Long identifies Africa, and the longing for home, as one of the key elements of black religion, because African Americans are a “landless people.”[xxi] Members of Peoples Temple called Jonestown the Promised Land. They looked forward with anticipation to having their own land, free of the problems of urban life: crime, drugs, unemployment. While the longing for the Promised Land is often spiritualized into an other-worldly hope in the Black Church, Jonestown realized that hope in the here-and-now.

The significant contributions that African Americans made to Peoples Temple, particularly to its agricultural project in Guyana, make it clear that Peoples Temple was a black religious group, both racially and culturally. Numbers alone do not tell the whole story. They do, however, provide the rationale for considering Peoples Temple and Jonestown within the context of black experience and black religion in America.

END NOTES

[i] The Assassination of Representative Leo J. Ryan and the Jonestown, Guyana Tragedy. Report of a Staff Investigative Group to the Committee on Foreign Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives. 96th Congress, 1st Session, 15 May 1979 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1979), 112-126.

[iii] These documents come primarily from Peoples Temple Records, California Historical Society, MS 3800.

[iv] More than 90% of the passport and membership photos of Temple members depict black men, women, and children.

[v] This figure over-estimates the number of survivors because we chose to err on the side of presuming people were alive rather than dead.

[vi] The Assassination of Representative Leo J. Ryan and the Jonestown, 720-774. This information is available here.

[vii] Sixteen beneficiaries received two checks, either for cost of living increases, or for dependent minors.

[viii] We also noted 20 sibling groups comprising two or more siblings, with no other family present.

[ix] Occupational Records, Peoples Temple Records, California Historical Society, MS 3800.

[x] Mary McCormick Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown (Syracuse NY: Syracuse University Press, 1998), Appendix A, 145.

[xi] C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya, “Daddy Jones and Father Divine: The Cult as Political Religion,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, 28-46. Maaga critiques the deprivation theory as an explanation for Peoples Temple’s appeal for African American members, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown, 81-82.

[xii] See Lincoln and Mamiya, and Archie Smith, Jr. in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, and Chapter VIII in Archie Smith, Jr., The Relational Self: Ethics and Therapy from a Black Church Perspective (Nashville: Abingdon, 1982).

[xiii] The list of Planning Commission members was generated primarily from FBI documents RYMUR 89-4286-1207, and 89-4286-1557.

[xiv] Thanks go to John R. Hall for making this point.

[xv] We appreciate Laura Johnston Kohl’s help in assessing the validity of this organizational chart.

[xvi] If the chart had genuinely been valid as of 12 July 1978, the name of either Debby Layton or Teri Buford would have been listed as a financial officer. Debby Layton defected in May 1978, and Teri left in October, however, which might explain their absence, especially if the chart had been created in November. The names of other of Jim Jones’ trusted advisers — including Mike Prokes and Karen Layton — are also missing. Dick Tropp, whose voice appears on several Jonestown tapes, does not appear on this chart. Neither Tim nor Mike Carter, who were spared from the deaths at Jonestown in order to smuggle a briefcase full of cash to the Soviet Embassy in Georgetown, are on this chart.

[xvii] These names appear in FBI documents RYMUR 89-4286-1557, -1207, -1681, -1552, and -1562.

[xviii] Miles Mark Fischer, “Organized Religion and Cults,” in African American Religious History: A Documentary Witness, 2d ed., ed. Milton C. Sernett (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 464-472, here 469; Arthur Huff Fauset, Black Gods of the Metropolis: Negro Religious Cults of the Urban North (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944), 80-81; and Melvin D. Williams, Community in a Black Pentecostal Church: An Anthropological Study (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1974), 5-13.

[xix] Joseph R. Washington, Jr., Black Sects and Cults (Garden City NJ: Doubleday, 1972), 17.

[xx] Catherine (Hyacinth) Thrash, as told to Marian K. Towne, The Onliest One Alive: Surviving Jonestown, Guyana (Indianapolis: M. Towne, 1995), 90-91.

[xxi] Charles H. Long, “Perspectives for a Study of African-American Religion in the United States,” Significations: Signs, Symbols, and Images in the Interpretation of Religion (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986), 173-184.