(Editor’s note: Larger pdf versions of the charts depicted below appear on this article’s companion page, Demographics at a Glance.)

More than fifteen years ago I conducted a demographic analysis of the residents of Jonestown, cataloguing place of birth, occupation, race, age, and gender. I first presented my findings at the 2002 annual meeting for the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in Salt Lake City.[i] My first article on the subject appeared two years later in a volume I co-edited with Anthony Pinn and the late Mary Sawyer: Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America.[ii] It came out in an abbreviated version on the Alternative Considerations website.[iii] The basic and most important findings generally concurred with initial demographic profiles produced by Archie Smith Jr., John R. Hall, and Mary Maaga:[iv] that is to say, the majority of Jonestown residents were female African Americans, and nearly three-fourths of those who died in Jonestown were African Americans.

More information has become available since the initial research was conducted.

Documents generated by members of Peoples Temple, recovered by the FBI at Jonestown, and obtained through the Freedom of Information Act have served as the primary sources of new information. In addition, former members of the Temple have literally spent years compiling data and writing analyses of life in Jonestown. They have developed extensive catalogs of everything from jobs performed in Jonestown to what people in the community ate for dinner.

The present article, therefore, updates and amends previous findings. Some of the research done prior to 2004 remains more or less valid or has not been superseded by additional studies. For example, the methodology outlined in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America has not changed dramatically. Some conclusions, however, changed radically with the new information, so it might be best to consider the present report a supplement to earlier studies. It should be read in tandem with them, and not solely on its own.

How Many Died?

No official, government-generated catalog of those who died in Jonestown exists. The closest such item, published in the House Committee Report on the death of Leo Ryan, is a list compiled as of December 17, 1978 which “identifies those deceased from Jonestown where the next-of-kin or interested party has been notified.”[v] About 550 names appear, many of them misspelled. After initial under-estimations of the total death count on site during the first week of the disaster, the U.S. Army reported recovering 909 bodies from Jonestown.[vi] The final tally of 918 includes those 909 in Jonestown, five killed at the Port Kaituma airstrip, including Congressman Ryan, and four who died in the Temple’s headquarters in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital. This figure has been the starting point for giving names to those who died, a task undertaken in 1998 with the inauguration of the Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple website.[vii] That process continued well after the initial 2004 data analysis.

First, in 2007, a team comprised of an archivist from the California Historical Society, a co-director of the Jonestown Institute, and two Peoples Temple survivors embarked on an ambitious project to update the listing on the Alternative Considerations website by attempting to precisely identify every single person who had died in Jonestown, Georgetown, and the Port Kaituma airstrip. “After months of work—compiling Jonestown census records, reviewing lists made by Jonestown survivors in 1978 to help the FBI in identification, incorporating dozens of corrections requested by relatives—the most accurate list of those ‘Who Died?’ went online in August 2008.”[viii] The addition of photographs to the descriptions of each and every victim graphically reinforced previous statistical analyses.

Second, the team made the decision to assume that children died in Jonestown if their parents had. The 2004 study over-estimated the number of survivors by sixty people by excluding the unidentified children. Since no children had miraculously turned up in the intervening decades, it seemed reasonable to conclude that they had died.

Another effort to identify those who died was made in 2011. That May, four granite plaques which listed the names of all who died on November 18, 1978 were installed at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California. The inclusion of the name of Jim Jones, the leader of Peoples Temple, on one of the plaques, caused some controversy, with critics likening it to putting Adolf Hitler’s name on a Holocaust memorial. Organizers saw the monument, however, “as a historical document which will survive long after all people associated with the tragedy of 1978—and their passions—have died.”[ix]

Though we start with the figure of 918 fatalities, we have only been able to identify 916 of that number, so the analysis in this paper is based upon that figure. Further, since four non-Temple individuals died at the Port Kaituma airstrip—Congressman Leo Ryan and three journalists who had accompanied him on his trip—we will see that statistics are based upon 912. Who are the two “missing” individuals? We might explain it by possible double counting of two bodies. Or, somehow two people who died there may have been neglected. These might have been Guyanese children or others on-site but unknown. Finally, the actual figure could be 916 rather than 918.[x]

Who Lived in Jonestown?

In 1978, Peoples Temple had five branch operations: three in California (Redwood Valley, San Francisco, and Los Angeles) and two in Guyana (Georgetown, the capital city, and Jonestown, located in dense jungle near the border with Venezuela). With the mass migration of Temple members to Guyana in 1977, the California operations became greatly truncated, though several hundred people still attended worship services in San Francisco and Los Angeles. A ranch in Redwood Valley continued to function. But the foremost task of the California centers was to raise money for the agricultural project and to administer communications and operations stateside. The Georgetown center, located in a neighborhood known as Lamaha Gardens, was the hub for intake of new immigrants into Guyana. It was also the guest house for those who needed medical attention, who were engaged in diplomacy with the Guyana government, and who were begging for money on the streets, another fundraising challenge.

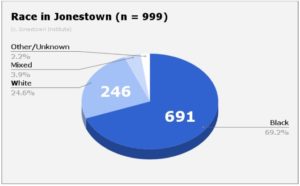

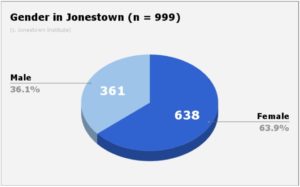

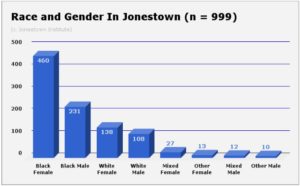

By far the largest single group of Temple members lived in Jonestown. If we add the number of those who died (n = 912) to those who survived (n = 87) we come up with about a thousand people living in Jonestown.[xi] Clearly that number fluctuated with people coming and going from Georgetown, but it seems solid. The community was overwhelmingly African American (Figure 1) and female (Figure 2). About 70% were black, 25% were white, and the rest were of mixed race or unknown ethnic origin. Equally striking, perhaps, is that slightly fewer than two-thirds were female. The principal explanation for the racial imbalance reflects the fact that the vast majority of Temple members in California were African American; indeed, their share of membership was greater in the U.S. than in Guyana. The disproportionate gender balance is less easy to explain, though conventional analyses indicate female membership in religious groups tends to be generally higher than that of men. Another possibility comprises the life care packages Peoples Temple offered to senior citizens, along the lines of retirement programs available from other religious organizations; general population statistics show that older women outnumber older men. The fact that 16 percent of those living in Jonestown were females 61 and older suggests this as likely.

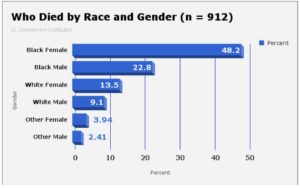

Figure 3 combines the elements of race and gender, and vividly reveals a preponderance of African American women: nearly half, at 46 percent. Black males made up almost a quarter, at 23 percent, with white females 14 percent and white males 11 percent. Whether these proportions are reflected in the leadership structure in Jonestown is discussed below.

These figures do not depart much from those presented in 2004. Nevertheless, while the current statistics are fairly reliable, we believe that they may underestimate the number of biracial individuals who lived in Jonestown. Some people identified as black in the records may in reality have been of mixed race. Although this is less of a problem for children, since their parents were known and could be racially identified, it was a greater problem for young adults and adults in general, where racial heritage was unknown. Some individuals were identified as black by virtue of skin color rather than parentage. Related to this is the issue of transracial adoptions. Peoples Temple members seemed to follow national trends in the U.S., in which white parents adopted, or fostered, black children at a higher proportion than black parents adopting or fostering white children.

It appears that some racial boundaries were fluid in family relationships, although not in the Jonestown hierarchy itself. Blackness was valorized, rhetorically-speaking. Some whites and most biracial children and young adults wore their hair in afros, if they could. Yet there were few African Americans at the highest levels of authority.

It appears that some racial boundaries were fluid in family relationships, although not in the Jonestown hierarchy itself. Blackness was valorized, rhetorically-speaking. Some whites and most biracial children and young adults wore their hair in afros, if they could. Yet there were few African Americans at the highest levels of authority.

Where Did They Come From?

Because we have personal data only for those who died, the listing of place of birth is based upon identification of the dead. With better records, however, like photocopies of passports, the information is more accurate. Using those indicators, we find that eleven states account for 753 of the Jonestown dead. Almost half of this cohort were born in California, with 358 (See Table 1). But when we look at the distribution of births by region, we see that 337 of the 912 who died came from the South, and that 95 percent of them were African American (See Table 2). Adding the numbers from California, Indiana—where the Temple began—and the southern states, it is clear that the majority, 81 percent, came from three areas. Of the remaining 39 states, all but 10 had at least one native son or daughter who died in Jonestown; and one individual was born in Washington, D.C.

Table 1. Top Eleven States of Origin

| State | Black | White | Mixed | Other | Total |

| California | 226 | 98 | 24 | 10 | 358 |

| Texas | 109 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 117 |

| Louisiana | 55 | 1 | 56 | ||

| Indiana | 20 | 31 | 1 | 52 | |

| Mississippi | 49 | 49 | |||

| Arkansas | 43 | 1 | 44 | ||

| Oklahoma | 17 | 2 | 19 | ||

| Alabama | 17 | 17 | |||

| Illinois | 9 | 1 | 2 | 12 | |

| Missouri | 9 | 3 | 1 | 13 | |

| Washington | 4 | 9 | 13 | ||

| TOTAL | 753 |

Table 2. The Southern Presence

| State | Black | White | Mixed | Other | Total |

| Texas | 109 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 117 |

| Louisiana | 55 | 1 | 56 | ||

| Mississippi | 49 | 49 | |||

| Arkansas | 43 | 1 | 44 | ||

| Oklahoma | 17 | 2 | 19 | ||

| Alabama | 17 | 17 | |||

| Missouri | 9 | 3 | 1 | 13 | |

| Georgia | 11 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Tennessee | 10 | 10 | |||

| TOTAL | 337 |

Where did the others come from? Nine Jonestown residents were born outside the United States, including two Korean adoptees.[xii] An additional fifteen children were born to American parents in Guyana between 1977 and 1978.[xiii] Finally, eight Guyanese children under the age of sixteen died in Jonestown.[xiv] Half of this number had already been adopted by Jonestown residents or were in the process of being adopted.

Who Died?

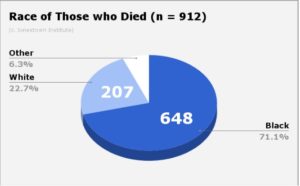

The racial proportion of those who died approximates that of the people living in Jonestown: 71 percent were black, 22.5 percent were white, and 6 percent were of mixed or other backgrounds (Figure 4). Almost one-half of those who died were African American women, and about one-fifth were African American men (Figure 5), again corresponding to the number of those who lived in Jonestown.

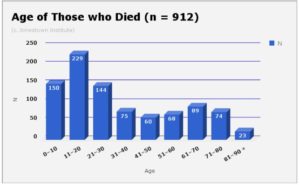

It has long been known that many children died in Jonestown, but a bar graph dramatically illustrates this (Figure 6). There were 379 children and young adults aged twenty and under who died. (Because we have presumed that children whose parents died in Jonestown also perished, the number of those aged 10 and under has increased from earlier calculations.) Coupled with 186 senior citizens, aged 61 and older, we have a sizeable non-productive workforce: 565 out of a thousand people. Of course, many teenagers worked in Jonestown, as did many of the senior citizens. Few escaped the hard physical labor demanded by an agricultural project situated in tropical jungle. Moreover, Social Security checks of retirees totaling more than $36,000 helped support the community financially,[xv] as did various cottage industries—such as soap- and doll-making—in which seniors were engaged.

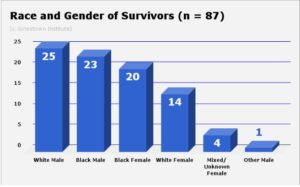

Only 87 people, or less than one-tenth, of the total Jonestown community survived (Figure 7). The disproportionate number of male survivors, compared to the Jonestown community overall, reflects the fact that the basketball team, comprised solely of young men, was playing in Georgetown; in addition, five men and only one woman were aboard two different boats—one in the Caribbean and the other in the Port Kaituma River—as the deaths were occurring.[xvi] Other men and women were in the capital city for various reasons. Eleven survivors left Jonestown on the morning of November 18, including two family groups, by pretending to go on a picnic and fleeing up the railway tracks to Matthews Ridge.[xvii] Seven escaped the deaths by leaving, hiding, or sleeping.[xviii] Finally, one survivor, Joyce Parks, was in Venezuela buying medical supplies.

Family Trees

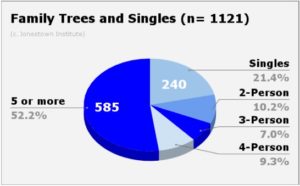

Thanks to the work of Kathryn Barbour and Fielding McGehee, the extent of the family connections that existed in Jonestown has become much clearer than it was at the turn of the century. Barbour’s photo remembrance album Who Died, coupled with her Birthday Project on Facebook, have revealed unknown family connections as survivors and relatives comment on her work.[xix] McGehee’s creation of family trees—which gathered together the data found in individual profiles—was enriched through receipt of FBI documents received under the Freedom of Information Act.[xx] Most important in this regard is the gross underestimation of family groupings comprising five or more members made in previous analyses.

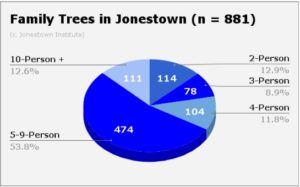

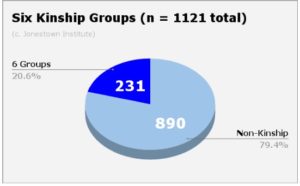

Approximately 240 individuals, or 20 percent, appear to have had no family ties in Jonestown; although this number may decrease as more connections are made, this is consistent with previous findings. Almost 80 percent of those remaining lived in 191 “family trees,” an increase of nine families from our last reckoning (Figure 8).[xxi] We defined a family tree as any group of two or more individuals who had a biological, marital, or longstanding relationship with each other. Because some individuals were part of several family trees, they were double- and triple-counted, which explains why n = 1121 in Figures 8 and 10. Two-thirds of the family trees comprised five or more branches, or members (Figure 9). The exclusion of singles from this grouping explains n = 881. Perhaps most striking is that the number of people belonging to family trees of ten or more persons almost equals the number of those belonging to trees with only two persons.

Equally remarkable is the fact that six kinship groups—in which family trees are connected by marriage or other relationships—account for 20 percent of the total Jonestown population (Figure 10). The six kinship groups, the number of families, and the total number of members appear in Table 3.

Table 3. Kinship Groups

| Kinship Groups with Families and Total Membership | ||

| L. Jones | 10 families | 88 |

| Cordell | 6 families | 48 |

| Touchette | 6 families | 37 |

| John James | 4 families | 23 |

| Wagner | 3 families | 19 |

| Jackson | 3 families | 16 |

Jim Jones was connected to 7.8 percent of the total population of Jonestown by family ties (n = 1121) and to 9.6 percent of those who died (n = 912). But more broadly, it is fair to say that almost everyone in Jonestown was related to someone else. This was not a group of single young adults, but rather a network of interconnected families made up of parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, guardians, foster parents, siblings, and adoptees who knew each other intimately. Paradoxically these family ties make the deaths both inexplicable (how could parents kill their own children?) and understandable (how could family members leave anyone behind?).

What Did People Do?

In the 2004 study we attempted to identify the occupations of individuals prior to their move to Guyana.[xxii] These findings have not changed, since they were drawn from the Temple’s own records: contrary to popular opinion, members did not come from the poorest levels of society, but rather from the working and professional classes. More recently, however, we have learned that at least twenty-seven individuals who died had worked in the U.S. Civil Service, with eight of those employed by the U.S. Post Office. Twenty-one veterans died, four of whom served in the Navy, and the remainder in the Army. We have been unable to calculate the total number of public school teachers who lived and died in the community, but, anecdotally, know there were quite a few.

Yet the catalog of the “Professions of Peoples Temple Members” is misleading, since once people moved to Jonestown, their jobs changed due to the attempt to create a self-sufficient society. As written then, “Many more people [were] working in agriculture, food preparation, and mechanical and building trades in order to support the community.”[xxiii] In 2006, Don Beck, a Temple member living in Redwood Valley in 1978, attempted the herculean task of identifying every job performed in Jonestown and determining who did it.[xxiv] It may be more helpful to note those who were not assigned jobs, or whose duties were unknown. Beck came up with 296 school students; 41 toddlers and preschoolers; 32 infants; and 111 who either had no jobs assigned, or whose jobs were unknown. Most in this last category were senior citizens.[xxv] This totals 480 people who probably were not contributing to the project’s economic viability, though as mentioned above, some seniors continued to labor, and some teenagers undoubtedly did field work. A separate article is needed to fully analyze the data Beck compiled.

What deserves emphasis here is that a racially-based hierarchy existed in Jonestown. The 2004 study discussed this by using an organizational chart found in Jonestown, and dated 1 July 1978.[xxvi] Additional documents, however, strengthen the argument that real power remained with Jones and a cohort of white, predominantly female, advisers. A tally of department supervisors drawn from the Temple’s own records show a decline in black leadership as time passed, though there is a slight bump after October 1977, the latest data we used (Table 4).[xxvii]

Table 4. Black Supervisors

| Date | Heading | Total # Listed | Black | White | % African American |

| Unknown | Personnel Codes | 11 | 6 | 5 | 55 |

| Unknown | Dept’s and ACAO Teams | 24 | 12 | 12 | 50 |

| Mid-1977 | Accounting Guide | 173 | 69 | 102* | 40 |

| After Oct 1977 | Accounting Guide | 184 | 81 | 100* | 44 |

* Some individuals were of mixed racial ancestry

When we evaluate the number of African American supervisors and department heads out of the total community, we see that they are greatly under-represented. Although blacks made up close to three-quarters of the population, they account for less than 10 percent of the leadership in 1977 (that is, 81 out of 999). Even calculating a non-productive labor force of 480, per Don Beck’s figures, we have a leadership cadre of only 16 percent (81 out of 519). If we were to consider the fact that certain whites, as well as blacks, had multiple roles, this percentage might increase slightly, but would never approximate the racial profile that characterized the community.

We also have a clearer picture of the composition of the Jonestown Security Team than we did in 2004. Survivors who were interviewed by the FBI upon returning from Jonestown—and were still stunned by the events of the previous weeks—inflated the size of the force; they named 67 individuals as members of the small cohort of residents who were armed and believed to be very dangerous. An organizational chart of the group reveals a much smaller, but still highly African American, squad.[xxviii] Seventy percent of the 39-member crew were African American, with 13 males and 14 females. The women primarily did administrative work, while the men actually patrolled Jonestown. In this instance, the proportion of blacks to whites mirrors the overall project.

Finally, there is the question of whether African Americans performed manual labor at a rate disproportionate to that of whites. Don Beck came up with a total of 250 individuals working in “Agriculture and Livestock.”[xxix] These included categories such as analysts, animals, gardens, insecticides and fertilizers, land clearing, land cultivation, orchards, and more. The tally of laborers in the category “work crews” is 121, with 26 of the workers being white; thus 20 percent of the field hands were white, a bit less than the 24.6 percent of whites living in Jonestown. With 70 percent of the residents being African American, we would expect to see blacks outnumber whites in all categories by a factor of three. As noted above, this is not the case when it comes to leadership roles,.

Work assignment begs the questions of who was benefiting and who was exploited in Jonestown. As early as 1980, two University of Guyana sociologists called the agricultural project “The Jonestown Plantation.”[xxx] Professors Lear Matthews and George Danns argued that the relationship between Jim Jones and his followers was that of master to slave, especially in Jones’ use of white lieutenants to carry out orders. The majority of those who lived in Jonestown were African Americans who were brought to the settlement “under slave-like conditions,“ in which they gave up all their possessions, were cut off from their families, and “were forced to become tools of production.”[xxxi] Like the colonial plantation systems, Jonestown was a total institution, which carefully scheduled and closely monitored its inhabitants’ (read slaves’) activities. Moreover, harsh punishments were meted out to control dissent and to prevent escape. “Jonestown was an atavism,” they concluded, “a recreation of a slave plantation with similar characteristics.”[xxxii]

To argue that Jonestown residents participated in their own victimization—which they did in community meetings, in the fields, in security enforcement—ignores the fact that no one could leave. If freedom of movement had been available, then the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, as it was called, might have become a model utopianist community. Without that liberty, however, whites and blacks alike were slaves. Thus, the characterization of Jonestown as a plantation has some truth to it, despite the racially-charged nature of the word plantation.

Analysis and Revised Conclusions

In 2004, we concluded that not only was Peoples Temple a racially black institution but that it was also culturally black. By racially black, we meant, and continue to mean, that African Americans made up the vast majority of members, residents, laborers, and leaders who contributed to the growth, dynamism, and financial support of Peoples Temple. By culturally black, we intended to say that the Temple embodied one type of black religious style in its progressive worldview, its worship practices, and its goal of a this-worldly, rather than other-worldly, paradise. Did this style, however, express black religious substance?[xxxiii]

As long as the Temple was led by a white preacher who surrounded himself with a corps of white operatives, the cultural blackness of Peoples Temple must remain problematic. Nevertheless, the sheer density of the black experience imbricated within the life of the Temple should not be ignored. As observed in the conclusion to the 2004 analysis, “numbers alone do not tell the whole story.”[xxxiv] We would add, however, that they tell an important part of the story, and one that needs telling.

Deep and heartfelt appreciation go to Fielding McGehee for his help in garnering the statistical data used in this paper. I also want to thank Leslie Wagner Wilson for her insights, which informed my thinking.

Notes

[i] Rebecca Moore, “Race and Family in Jonestown: What the Numbers Say.” Paper given November 2002 at the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Salt Lake City, UT.

[ii] Rebecca Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary Sawyer, pp. 57–80 (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004).

[iii] Rebecca Moore, “The Demographics of Jonestown,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, accessed 20 July 2017.

[iv] Archie Smith Jr., The Relational Self: Ethics and Therapy from the Black Church Perspective (Nashville: Abingdon, 1982); John R. Hall, Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1987); and Mary McCormick Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1998).

[v] U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs, “The Assassination of Representative Leo J. Ryan and the Jonestown, Guyana Tragedy: Report of a Staff Investigative Group” (Government Printing Office: Washington, D.C., May 15, 1979), 112–126.

[vi] Joseph B. Treaster, “Toll at Jonestown set at 909 by U.S. as Army Pulls Out,” New York Times (27 November 1978), accessed 22 August 2017.

[vii] “Who Died,” Alternative Considerations, accessed 20 July 2017.

[viii] Rebecca Moore, “The Stigmatized Deaths in Jonestown: Finding a Locus for Grief,” Death Studies 35, no. 1 (January 2011): 51.

[ix] Fielding M. McGehee III, “The Campaign for the New Jonestown Memorial: A Brief History,” The Jonestown Report 13 (October 2011), accessed 21 August 2017.

[x] According to an unsubstantiated rumor, the 918 total came by counting the number of skulls recovered from Jonestown.

[xi] We previously reported 1020 members living in Guyana as of November 18, 1978. Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” 61.

[xii] Lew Jones, Betty Jean Tschetter (South Korea); Deirdre McMurry (Germany); Dov Lundquist (Mexico); Avis Breidenbach, Cleveland Garcia (Belize); Santiago Rosa (Honduras); Peter Wotherspoon (Chile); and Ethel Belle (British West Indies). Fielding McGehee, “How Many Guyanese Died in Jonestown? Did Any Other Non-Americans Die?”, accessed 22 August 2017.

[xiii] Jonathan Jackson, Kamari Rosa, Zateese Simon, Martin Smith, Ju’Quice Turner, Kaywana Carter, Malcolm Carter, Chaoke Jones, Ebony Duncan, Kennard Wilhite, Camella Griffith, Charles Henderson, Shaunte Marshall, Takiya McMurry, Cuyana Minor. This list excludes Marshawn Cobb, who was born in May 1978 but died two weeks later. Compiled from “Who Died” list, accessed 22 August 2017.

[xiv] Dereck Dawson, David George, Gabriel George, Phillip George, Jimmy Gill, Neal Welcome, Monyelle Jones, Marchelle Jones. McGehee, “How Many Guyanese Died in Jonestown?”

[xv] Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” 65.

[xvi] Phil Blakey, Richard Janaro, Helen Swinney, and Charles Touchette were on the Albatross; Herbert Newell and Clifford Gieg were aboard the Cudjoe.

[xvii] The Julius Evans family (5 people), the Leslie Wilson family (2 people), Richard Clark, Robert Paul, Johnny Franklin and Diane Louie.

[xviii] Tim and Mike Carter and Michael Prokes were given guns and money, and told to head for the Soviet embassy; Stanley Clayton and Odell Rhodes slipped away; Grover Davis hid in a ditch; and Hyacinth Thrash slept through it all.

[xix] Kathryn Barbour, Who Died on November 18, 1978 in the Jonestown, Guyana Mass Murder-Suicides (San Francisco: Katbard Publishing, 2015).

[xx] “Family Trees,” accessed 20 July 2017.

[xxi] While in the previous analyses we called these groupings “family units,” they are more appropriately considered as trees, with many branches. See Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” 66.

[xxii] Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” 68–69.

[xxiii] Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” 68.

[xxiv] Don Beck, “Jonestown Organization,” accessed 23 August 2017.

[xxv] Don Beck,” Jobs/Activities in Jonestown,” Alternative Considerations, accessed 23 August 2017.

[xxvi] Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” 71. An updated version of this chart created by Don Beck does not alter earlier conclusions. Don Beck, “Jonestown Organizational Chart,” Alternative Considerations, accessed 25 August 2017.

[xxvii] Don Beck, “Administration,” Alternative Considerations, accessed 1 September 2017.

[xxviii] “Peoples Temple Documents Recovered by FBI (2009 Release),” Sec 075, RYMUR 89-4286, 2018, C-7 Daily Operations, Alternative Considerations, accessed 25 August 2017.

[xxix] Don Beck, “Jobs in Jonestown by Department,” Alternative Considerations, accessed 25 August 2017.

[xxx] Lear K. Matthews and George K. Danns, “Communities and Development in Guyana: A Neglected Dimension in Nation Building” (Georgetown, Guyana: University of Guyana, 1980); reprinted as “The Jonestown Plantation” in Eusi Kwayana, A New Look at Jonestown: Dimensions from a Guyanese Perspective (Los Angeles: Carib House, 2016), pp. 82–95.

[xxxi] Matthews and Danns, “The Jonestown Plantation,” 89.

[xxxii] Matthews and Danns, “The Jonestown Plantation,” 89.

[xxxiii] For a negative answer, see Monroe H. Little Jr., “Review of Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America,” in Indiana Magazine of History 102, no. 4 (December 2006); 392–93.

[xxxiv] Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” 77.

(Rebecca Moore is Professor Emerita of Religious Studies at San Diego State University. She is currently Reviews Editor for Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions and Co-Director of The Jonestown Institute. Her other articles in this edition of the jonestown report are The FBI and Religion: The Case of Peoples Temple; Freedom of Religion, Freedom of Information, and the National Security State; Representations of Jonestown in the Arts; and Joanstown: A Different Look at Guyana. Her complete collection of articles on this site appears here.)