I was deeply saddened when I heard the news in September 2016 that Phil Tracy had died. As an artist, I believe the great privilege of my life is to interview people as the basis of my work, to be taken into their confidence, and to be entrusted to tell their stories. So it was with Phil

I was deeply saddened when I heard the news in September 2016 that Phil Tracy had died. As an artist, I believe the great privilege of my life is to interview people as the basis of my work, to be taken into their confidence, and to be entrusted to tell their stories. So it was with Phil

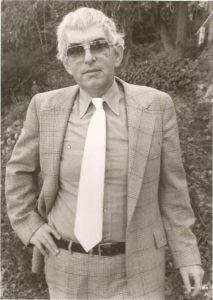

As with most people who have had any touch with Peoples Temple, Phil Tracy was greatly impacted by the events in Jonestown. When I met him, he really did seem like a character, a man who had walked right out of central casting as the classic, hardened reporter from a bygone time. He had largely given up any ambitions he had had as a young writer, and was writing restaurant reviews for a small local press to pay the bills.

Phil didn’t have a car, so I picked him up for our interview. He wanted to go to local bar. It was daytime, and the crowd in the dimly-lit bar seemed like a glum lot, a collection of lonely souls making small talk and nursing drinks. The place felt sad, as Phil did to me.

I ordered a coke and Phil ordered a scotch. We began to talk. It didn’t take long before Phil’s wise-cracking cynicism gave way to his warmth, sincerity, and thoughtfulness. We developed a quick rapport.

It was obvious that Phil deeply cared about this story, the people affected, and the people who died. Phil was an investigative reporter in the truest sense of the word. He came to this story in San Francisco at the height of Jim Jones’ political power, just before the mass exodus to Jonestown. He intersected with Peoples Temple at a time when the fabric of the dream was being tested by defections. Phil recounted with vivid detail his investigative tactics, the people he met, and the battles he fought to get the story out.

In the end, he and Marshall Kilduff, the reporter at The San Francisco Chronicle who partnered with Phil on the piece, did get the story out. Their article in New West, “Jim Jones is one of this state’s most politically potent leaders: but who is he? And what is going on behind his Temple’s locked doors,” was an expose on Jim Jones and Peoples Temple, disclosing details from the Temple’s inner circle. The article may have hastened, or even facilitated, the exodus to Jonestown.

Phil blamed himself for what happened at the end and admonished himself for not having done more. Once the mass exodus to Jonestown was complete, he went to Los Angeles, and as he put it, “I was trying to score screenplays. I just put it out of my mind.” And when the news started coming out on that Saturday night, he said he felt like the world’s worst failure.

As a human being, my heart went out to him. His regret was palpable. As a playwright, I saw Phil as a great character, a tough man with a fragile heart. The deaths in Jonestown had shattered his ambitions as a writer. Sitting at the bar with Phil – his hand on his drink, an obvious source of comfort to him, maybe even the only ground on which he felt he could stand – I saw a broken man.

He was a writer like me. I identified with him. I respected him. He said a lot of powerful things to me. One thing will stay with me forever: “Leigh, you never want to get involved in a story in which hundreds of children die, because you’re never going to feel good about it, and that’s what happened.”

Some people were able to separate themselves emotionally from what happened, but he said he wasn’t able to do so. “Eventually, I stopped writing, and I would be a fool and a liar if I said this wasn’t part of it.”

When Phil saw the premiere of The People’s Temple at Berkeley Repertory Theater in Berkeley, California in 2005, he sent a note: “Thank you for making art, a thing of beauty, for Jesus Christ’s sake, out of one of the worst moments of my life.”

It is truly a privilege to make art out of the worst moments in people’s lives, to transform tragedy, even if just for a few hours, into something beautiful, something that can be appreciated by the audience. The tragedy becomes a point of connection; the audience can relate in their own humanity to what happened.

Phil tried to the “right” thing, and everyone ended up dying. My experience is that there is not a single person who has lived through these events who hasn’t questioned their role in it: what might have happened had they only seen, had they only known, could a different choice have changed events, or even changed the outcome?

All the hope and promise of the people who died in Jonestown is a constant reminder of both the best in us and the worst in us, how events are set in motion and sometimes cannot be stopped, cannot be undone. All the hindsight in the world can’t change them.

If only his life were a fictional story, we could change the end. We could have him chasing the plane down, stopping it in its tracks, saving everyone’s life. Over the course of several hours of conversation, Phil’s cynicism gave way to a heartfelt admission of his own powerless to control or to change events. It may have been easier for him to blame himself than to contemplate the fateful inevitability of what happened, or the randomness of evil winning out over good, or the lines of the two so blurred as they were in Jonestown.

I celebrate the life and work of Phil Tracy, all of the stories and screenplays and books he never wrote as a result of what happened, and the ones that he did.

May he rest in peace, not as a failure, but as a writer who appreciated the power of words and of good reporting to create meaningful change.

(Leigh Fondakowski is the writer and director of the play, The People’s Temple, and the author of the book, Stories from Jonestown. Her writings for this website are here. She can be contacted through this website.)