of Information Act

(Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of the state of decomposition of the bodies in Jonestown.)

More than thirty years has passed since a single event in the Guyanese jungle changed our idea about cults, communes and Kool-Aid. Today, most people have heard of Jonestown and Jim Jones, but few actively link the events in 1978 with anything other than a phrase used in popular culture – drinking the Kool-Aid. Fewer people know what happened after the murder/suicides.

Who, for example, cleaned up Jonestown? Who moved the bodies? Why was it the charge of the United States military to go to Guyana and bring home those who had died in the jungle?

In the many accounts of Jonestown reported after the tragedy, the role of the military is barely mentioned, their deeds forgotten, and their mission deemed not exciting enough to document. In some conspiratorial accounts, however, the military has a larger role in the mass murder, sometimes even as the culprit. In an effort to separate fact from fiction, one only needs to look a little deeper and investigate those in the military who actually went to Guyana and dutifully repatriated over 900 Americans from a foreign land, service members who have been forgotten.

Jonestown has its own dark mystique that both repels us and intrigues us, yet there is so much more to the story than a mass death in the jungle. There are many false rumors or misleading conclusions and even more questions that are left unanswered. We try to simultaneously explain the event and dismiss as crazy that which we do not understand. Either way, we place it safely outside our experience to make it easier to ignore. This treatment, or dismissal, extends to those whose task it was the repatriate the survivors, treat the injured, and return the victims of the Jonestown tragedy to their home country. That job was assigned to United States military.

It may be that the United States military’s role was initially downplayed, overshadowed by the horror of the event that required its services, and buried in news coverage under reports of hit squads and hidden millions. Certainly it was soon overtaken by the events in 1979 as our embassies were attacked and burned in Pakistan and completely overrun in Iran. What is lacking from nearly every account of the tragedy in Jonestown is a solid history of the U.S. military’s involvement in repatriating not only the survivors, but the victims as well. This, it should be argued, must be corrected. We must recognize that confronting traumatic experiences and expressions of courage do not require combat, or life-threaten situations in a hostile situation. Sometimes, bravery comes simply doing one’s job without reward or recognition. The Air Force and Army did not “clean-up” cultists, but instead returned home the bodies of Americans lost in a Guyanese jungle.

* * * * *

As the report of Leo Ryan’s death hit the State Department, which had “the responsibility [for the safety] of these Americans, the press, the congressman’s party, and the cult members” asked the Air Force for its assistance in evacuating the dead and wounded. This action started the most unusual military airlift operation since the Berlin Airlift.

It was the Air Force that was notified first. Within hours of the attack, the State Department “asked for assistance” from the 437th Military Airlift Wing (MAW) stationed at Charleston Air Force Base (AFB) in South Carolina. An airlift capability was required to retrieve the survivors and the victims of the congressman’s party and to take down medical personnel. The Military Airlift Command (MAC) had been mobilized. By 0805Z (Zulu time according to official records) the first flight containing the 31st Aeromedical Evacuation Team from the 315 MAW (Reserve) had left Charleston AFB headed for Guyana. A C-141, tail number 40647, became the first of 46 C-141 flights to be used in the as yet unnamed mission; 45 were officially a part of the Joint Task Force.

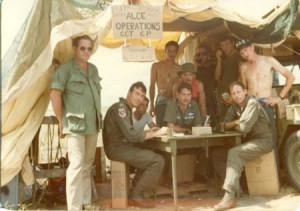

The first mission number was AVN1017-01, piloted by Capt. Tim House, and the lead physician was Lt Col Fred O. Bargatze, USAF. Their task, to evacuate the injured in a “politically-sensitive” environment, was left partially unclear. The sensitive nature of the mission was most likely due to several factors. First, the Government of Guyana (GOG), having already limited resources, wanted nothing to do with remedying what was ostensibly an American problem. One key request that highlights the Guyanese lack of preparedness was its appeal to the American State Department for fairly simple supplies, including 150 sleeping bags, five small electric generators, five HP outboard motors, two UH-1 (Huey) helicopters with crews, one U-21 (small twin engine aircraft) with crew, a 1 ¼ ton truck, one week’s worth of C-Rations, and blankets to support the field operations of up to 150 Guyanese Defense Force (GDF) personnel stationed at Jonestown. Second, the information coming from Guyana was scant at best, and wrong at worst. Third, in world history, an assassination of a foreign diplomatic official has led to armed conflict, but in this case, an American congressman had been murdered by Americans. The unknown nature of the mission required an added level of caution. Therefore, the aircraft transported four Air Force Combat Controllers (CCT) led by Capt John Buck, to provide aircraft security during the initial ground operations.

of Information Act

The first hurdle for the first flight into Guyana was actually getting to the wounded. The victims were on an unimproved dirt airstrip at Port Kaituma, and the C-141 was too large to land there. Instead, the medical staff headed to Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, 150 miles away from the site of the attack. The flight took approximately five hours. Upon arrival, they set up a “receiving station” in an area of the airport listed as “Jet Ramp South” which is adjacent to the airport fire station. This area would remain as the staging location for the Air Force’s C-141 aircraft throughout the airlift.

The night of November 18 was humid, and an evening rain slowly dissipated into the jungle. As the rain subsided in the early morning of the 19th, two small aircraft approached the runway in Guyanese capital where the 31st Aeromedical Evacuation Team was stationed. The two planes were inbound from Port Kaituma with the first victims aboard. The deceased had been left behind for one obvious reason; the medical staff could not help them. Among the wounded lucky enough to make it out of Jonestown, only one, Congressman Ryan’s aide Jackie Speier, was a member of the government. All other casualties were members of the press or from the Concerned Relatives group that had pressed for the visit. All told, eight wounded persons were to be treated and airlifted back to the Naval Hospital at Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, and Charleston AFB. One person, Steven Katsaris, accompanied his wounded son, Anthony, who had suffered a gunshot wound to the chest.

Prior to the first flight’s return, Dr. Leeb, a Navy Pathologist, was asked to stay behind to help with the removal of the bodies from Port Kaituma. Lt Col Bargatze had been informed that the “Guyanan (sic) government could not lawfully move the bodies” of foreign nationals. Whether or not this was true remains unclear. In addition to Dr. Leeb, two Air Force Combat Controllers stayed behind, again providing security and communications assistance. Col Malcolm Cahn-A-Sue of the GDF and the Head of the Guyana Airlines Corporation informed the crew that Jonestown and Port Kaituma were still not secured. In other words, hours after the suicides had taken place, no one had any idea what was really happening in Jonestown. There were the rumors of a mass suicide, but they still seemed too wild to be true.

of Information Act

Learning the fate of Jonestown became the next phase in the mission. The GDF advanced on foot from Port Kaituma to the compound, but they were hampered by heavy rain as well as extreme caution, since it was thought an armed contingent entering the Jonestown complex could incite further hostilities. Sunday would pass with little or no additional information and it would not be until Monday, November 20 that a second aircraft would arrive in Georgetown to pick up the first dead in the tragedy, Congressman Ryan and the newsmen. By this time, the GDF was entering Jonestown.

The second C-141 from Charleston AFB, piloted by Capt Keith J. Wolf (mission AJM1017-2, AC#60202) along with a crew of eight, headed for Timehri International Airport to retrieve the bodies of the Ryan and the three reporters. The mission capabilities were still so lacking at this point, that almost all communications, and the receiving of updates and news reports, were done via the aircraft. This included “communications with 21AF, the embassy, and other required agencies.” The one exception was the telephone inside the adjacent fire station that was used to call the U.S. Embassy in Georgetown. The poor communications would persist in the early stages of the mission and changed only upon the arrival of the Airlift Control Element (ALCE). As the second C-141 flight returned to Charleston AFB, it switched pilots and proceeded to Warner Robbins AFB, and then to San Francisco and finally to Los Angeles. Nearly 48 hours after the murder/suicides the mission became clearer. During this period, the first reports issued by the GDF that had entered Jonestown estimated that 300 to 400 people had perished in the commune.

The weekend had seen a flurry of activity in the State Department as the situation reports began to trickle in, yet the scope of the tragedy was still unknown. But with 400 dead – the number that the State Department used during a press conference Monday, November 20 – the agency realized that the Guyanese resources were not enough to handle such a massive undertaking. By late in the day on the 20th, 150 Guyanese forces were on the ground in Jonestown to secure the site and search the neighboring jungle for possible survivors, a number first estimated to be around 450. Those “survivors” were never found, since there weren’t any. Overwhelmed by the scope of the disaster, the Guyanese government asked the United States State Department to step in, and by doing so, it initiated the first phase of the Joint Task Force.

200903Z Nov 78 (Alert Order) – The Task Force

At 9:03 Zulu time, the JCS (Joint Chiefs of Staff) sent an Executive Order that read in part:

Subj: Executive Order – Return Of Deceased American From Guyana (U)

Ref: A. Jcs 200903z Nov 78 (Alert Order)

B. Uscincso Georgetown 201754z Nov 78 (Concept Of Operations)

C. Amembassy Georgetown 201755z Nov 78 (Notal)

1. (U) This Is An Execute Order By Authority And Direction Of The Secretary Of Defense.

2. (U) Situation: Preliminary Reports Indicate That As Many As 400 Members Of The Jonestown Peoples Temple Community May Be Dead Requiring Identification And Disposition.

3. (C) Mission: Return Deceased Americans To United States.

4. (C) Execution:

A. Course Of Action. Activate JTF And Deploy Forces To Guyana To Assume Custody Of Deceased And Return Remains To Dover AFB. Minimize The Number Of Personnel To Approximately 250. Authority Granted To Modify Concept Of Operations (Uscincso 201745z Nov 78) If Utilization Of Mathews (Sic)… (End Of Copy)

Key: Jcs – Joint Chiefs Of Staff, Uscincso – Commander In Chief, U.S. Southern Command, Notal – Notice To All, Jtf – Joint Task Force

The initial response called for medical personnel from the 601st Medical Company of the 193rd Infantry Brigade. Their mission was to rescue those who had “escaped into the jungle” and to treat those that had been poisoned. Jeff Brailey, a senior Army medic, was one of the first Americans into Jonestown, and his task was to provide an antidote to any persons who might have survived. Unfortunately, his mission was short-lived and futile. The poison was completely effective, and Brailey described standing alone in a silent field of bodies, a haunting scene that he will never forget.

To add more confusion to the situation in Jonestown, on Monday, November 20, the State Department went to the other extreme and reported that there were no “living persons there.” This was untrue. Several people had survived the massacre, including two elderly people: Hyacinth Thrash, who slept through the carnage only to awaken to a “ghost town”; and Grover Smith, who hid in the jungle. By the time Jeff Brailey and the medical staff arrived in Jonestown, thanks to a Guyanese Huey (UH-1H), most of the survivors had been transported out of the area. Some, like Stephan Jones, the son of Jim Jones, returned to Jonestown to help identify the bodies. Due to the scale of the recovery and Guyana’s inadequate resources, an airlift was ordered and Dover AFB was prepped to receive the deceased.

A key element in the mission was delivering the bodies to the capital for transfer to the States. This task was assigned to Howard AFB in Panama. Their mission was to send helicopters to transport the bodies from Jonestown to Georgetown. The contingent included three HH-53s (Jolly Green Giants), whose mission involved one of the more gruesome tasks: ferrying body bags. Following each flight, the helicopters were washed out with a fire hose, yet in one official report, Capt Skinner of the Medical Service Corps, US Army, ordered the HH-53 helicopters from Howard AFB to be stripped of insulation and thoroughly washed after the mission for “public health purposes.”

Photo courtesy of Thomas C. Wilson, used by permission

According to TSgt Thomas C. Wilson, “the reason for the washout of the helicopters after they would deliver bodies to Georgetown was because the bodies would be stacked on the aircraft like cordwood. They were just in body bags and the bags leaked.” Wilson, an Air Force C-141 Load Master (LM) stationed at Georgetown during the recovery operation, was tasked with verifying the loads to and from Guyana. The smell, unfortunately, was only the tip of the iceberg. The airport personnel were subjected to high humidity and heat, unsanitary conditions that were described as “inadequate/marginal” and water that either unavailable or of “questionable” purity. In addition, one report stated, “many personnel were not equipped to live under field conditions.” The unhygienic conditions lasted until the last body was retrieved and loaded for the United States. The clothing worn by all members of the Task Force who had come in contact with the bodies, burned their clothing at the end of the runway. Fed with clothing, the insulation stripped from the aircraft, and the cargo netting used to secure the human remains in transfer cases, the fire lasted for hours. Put simply, if it smelled, it was burned. Even that was not enough. After the mission, the stench of death was so thick the aircraft were deemed medically unsafe.

For the personnel at the airport, the heat, long hours, tedious working conditions and the constant stench of death took its toll. There were two cases of heat exhaustion during the operation, and a “contused foot.” In addition, the poor accommodations included tents and, if one were lucky, a room in a local airport facility, although these latter accommodations housed 10 persons to a room and were without air-conditioning. Some personnel, like the Air Force CCTs, slept outside in cots next to their communication gear. It is fair to say that during the recovery operation, “field preparedness” was lacking.

Water also became an issue of concern and a precious resource. What little water there was at first was made available by the GDF, but it had to be heavily chlorinated by Army medics. The first provisions of potable water were so questionable that the supply was deemed suitable for washing only. The GDF later provided a second “Water Buffalo,” and this time the water was potable when used with purification tablets supplied by the Army. The Air Force, however, had most of its water brought in country via Igloos aboard their MAC aircraft. As for basic hygienic concerns, Lt Col Wells’ field report stated, “No bathing or shower facilities were available. The fire station pump broke down, and during two 24-hour periods, no water was available to flush the toilets. Feces and paper piled up within them and flies were numerous.” Between November 20 and 27, the lack of sanitation became the norm for those on the ground at Timehri. Even the facilities at the fire station, whose mission is to use water to extinguish fires, were dependent upon a working pump of questionable reliability. The pump was also needed to recharge the tanks used for sanitation.

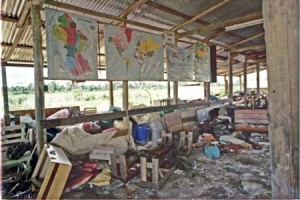

Like Jonestown, Timehri International Airport in Georgetown where the bodies had been ferried became a magnet for flies and gnats. If there was one redeeming feature of Guyana for the personnel working on the ground, it was the lack of mosquitoes. To minimize the flies, white sheets were used to cover the dark, olive drab body bags. The sheets help to mask some of the smell, but more importantly, countered the effects of the body bags’ dark coloring that sped the process of decay.

The problem of decay was present from the start of the operation. The process of putrefaction was accelerated in the heat and moisture of the jungles surrounding Jonestown. The members of Peoples Temple had been left in the jungle heat and rain for two days prior to their discovery, and even though the recovery operation revved up quickly, it would be up to six days before all the victims were collected and shipped to the capital. It was during this time that the condition of the deceased deteriorated considerably. As the putrefaction process begins, the body breaks down resulting loosening of the skin. The extremities become yellowish, and the skin becomes pliable and falls off the body.

Photo courtesy of Thomas C. Wilson, used by permission

The second effect of putrefaction is that identification through simple observation becomes difficult, if not impossible. Many victims were not identified until they were examined in Dover. By that time, race, sex and age of many victims became impossible to be determined as the skin has lost its coloring, the bodies bloated, and once distinct features disappeared. With some assistance of some surviving Peoples Temple members, the Army Graves Registration Units (GRREG) on the ground did what they could helping to identify many of the victims, but the main function of the GRREG units was a quick resolution to the mission and this meant loading the victims in body bags. This was made abundantly clear on 240430ZNOV 78 (November 24 at 430Zulu time) as a Situation Report (SITREP) confirms, “No additional attempts are being made to identify bodies in Guyana.” Although left unstated in the SITREP, it is clear that putrefaction is the reason for the termination of the identification efforts.

One of the strangest stories to come out of the GRREG units in Jonestown was documented by Jeff Brailey, the Army medic in Jonestown, in his book, The Ghosts of November. Brailey wrote that Mr. Muggs, Jim Jones’ chimpanzee was also airlifted out of Guyana. Unfortunately, this is not confirmed in the official record but it is possible that the GRREG units also collected Mr. Muggs for hygienic reasons, thereby “cleaning the site” as directed.

The GRREG assigned to the 530th Graves Registration Detachment on the ground in Jonestown used Peoples Temple vehicles to assist in transferring the dead from Jonestown to the Landing Zone. It may be somewhat ironic that this may have included the infamous Temple tractor seen in the NBC news footage of the assassination of Congressman Ryan. The vehicle used at the start of the tragedy, was also used at the end. And, just like the scene at Timehri, the GRREG units lined up the body bags along the landing zone in Jonestown where they awaited a helicopter airlift out of the jungle. In Timehri, however, they were awaiting a flight home.

As the helicopters shuttled back and forth from Jonestown, they were unloaded by hand to a staging area along the edge of the runway. The helicopters would have completed 30 sorties by the time their mission was done: an average of 30 people per mission were loaded and unloaded by hand. Once at Timehri, the bodies were placed onto a truck and driven to another staging area where they could be loaded into transfer cases.[1] The transfer cases were then placed onto pallets and then carried into the awaiting C-141s for transport to the States.

The initial round of 240 transfer cases was ordered into service on 22 November. The first round obtained for the mission included 96 transfer cases from Byrd Field in Richmond, Virginia; 72 cases from Oakland; and 72 cases from Hill AFB in Utah. It was also noted that the “DLA [Defense Logistics Agency] will continue to locate transfer cases, should they be required.” They were. Due to the enormity of the tragedy – and the early low estimates on the number of fatalities – it soon became apparent that more transfer cases would be needed. On November 24, an additional 50 transfer cases were located at Rhein Main AFB in Germany and “forty plus cases” at Wiesbaden, West Germany. This last request was soon cancelled, since the time required to ship the transfer cases would placed the delivery at the tail end of the operation; moreover, sufficient resources were already rerouted to Guyana. This lull, however, would not last. The next morning, Saturday, November 25 – a full week after the deaths – a request was placed for an additional 144 transfer cases as “more bodies were found.” The total number of bodies had been determined to be a staggering 910. As for the non-military transfer cases seen in some of the photographs during the operation, TSgt Thomas Wilson explained:

In the meantime, the helicopters were still bringing in bodies and we were running out of transfer cases. The decision was made at a higher level to send aircraft through Knoxville, TN and pick up caskets from a casket manufacturer in that area. One of the pictures shows us unloading a pallet of new caskets. If I remember correctly, the caskets came in with the lining removed. This allowed us to get more bodies per casket.

The maximum number of transfer cases per flight was 81. Pallets of transfer cases were unloaded and loaded as fast as they could be found. Transfer cases and standard coffins were being collected from all available stores. Many cases were sent back from Dover AFB only to be used again. The transfer cases were treated much like the helicopters and the C-141s, in that they were unloaded, washed out, and sent back to Guyana or – as the official records indicate – they were “Recycled.”

However, this does not indicate a business-as-usual attitude by the aircrews or the Air Force. Human remains are treated with a certain sense of decorum and respect. As an example, where the gender of a body was known, the remains of a woman were never placed below a male. Moreover, the orientation of the transfer cases changed depending upon whether they were empty or occupied. TSgt Wilson explains,

If you look (at some of the photos), you will notice the cases run crosswise on the cargo pallet. This indicates they are being unloaded and coming to us. If they had bodies in them, the cases would be placed on the cargo pallet so they would be running long ways in the aircraft.

The difference between loading and unloading the transfer cases may also explain the discrepancy between field accounts and SITREPs indicating 81 or 83 transfer cases per flight.

The transfer cases used during the Joint Task Force mission were designed to have a low platform and a raised upper section. The low section allowed for easy removal of the body when the case is open. The downside is the case would be difficult to properly load and seal in this position. Therefore, the upper section was placed on the ground upside down. This allowed for easier loading of the body bags since this position created a deep cavity in which to place the body bag. However, lifting the bags created its own gruesome issue. As the bags were lifted, body fluids leaked from the decomposing bodies contained within the bags, covering those who were tasked with placing them in the transfer cases. When the cases are secured, they are rotated over, but like the body bags, the cases also leaked. Under normal use, bodies are not left outside long enough to require an airtight body bag. The operation in Jonestown was different.

Since each C-141 could take 81 “palletized” transfer cases, one might assume that each mission carried only 81 victims. This number can be misleading for the reason that some transfer cases contained more than one victim. Considering the requests for more transfer cases, and the addition of traditional coffins seen in some photographs to augment the shortage, the combined transfer of remains in a single case became a necessity. The alternative would have been to let the bodies decay in the hot Guyanese sun for several more days while awaiting individual transfer cases, thereby extending the mission and possibly losing any evidence of foul play. The unorthodox decision to “double up” on the transfer cases appears to have originated with Lt Col Wells, the on-site ALCE Commander. This, it should be noted, was not Air Force policy and was done in an effort to expedite the return of the victims. The flights continued until all the remains were in Dover, Delaware, but at one point, it was estimated that there were as many as 200 full body bags on the runway in Georgetown awaiting transfer cases. As TSgt Thomas Wilson noted,

The helicopters would bring the bodies to us, they would be unloaded and put on the ramp, the helicopters would be washed out by a fire truck, they would take off, the bodies would be loaded on a truck and transported to the staging area to be put in transfer cases as they became available and then loaded on the C-141 and sent to Dover AFB. (emphasis added)

Once loaded, the C-141 headed to Dover AFB where crews of Air Force mortuary technicians and pathologists worked around the clock, embalming those that could be embalmed, conducting seven autopsies – including that of Jim Jones – and looking for additional signs of foul play. But the last flight was the one that had the most impact on those in the Task Force. It contained 83[2] transfer cases, loaded with 184 bodies “each with its own body bag” stating, “These were the children of Jonestown.” TSgt Tom Wilson noted that there were actually two flights where there were more bodies in the shipment home than there were transfer cases.

All told, there were 21 missions in direct support of the Task Force. The 20th MAS flew supplementary “wild card” missions but it was the 41st MAS that proved to be the beast of burden for the Joint Task Force. Lt Col Wells’ field report stated that “45 C-141 and 3 C-130 transited Timehri in support of JTF operation between 20 and 27 November,” that 603 passengers had been flown on MAC aircraft, and 690.5 tons of cargo had been moved during the operation. In addition to the MAC aircraft used during the Joint Task Force, the operation included the use of five UH-1 helicopters (that frequently broke down), one OH-58 (observation Helicopter), one U-21[3] , three HH-53 Jolly Green Giants and two CH-130 (that also broke down during the mission). The U-21, UH-1s and the OH-58 were used primarily for “logistics support” and not for the transfer of human remains. Other equipment used included two jeeps – the CCTs M-108 communications load-out and an M-151 – generators, an AT Forklift (a 10,000 lb lift adverse terrain forklift seen in several photos of the operation), various HF, UHF and VHF radios, as well as a “Jackpot Package” used for communications.

Photo courtesy of Thomas C. Wilson, used by permission

The Joint Task Force had a maximum complement of 69 officers and 227 enlisted personnel at the height of the mission on November 24, 1978, yet the total number of those involved is still unclear. Some personnel may have only been “in-country” for a brief period of time, while others, such as the CCTs, stayed after the mission officially ended, since two Air Force CCTs were reassigned to the American Embassy to assist with the subsequent investigations into the tragedy.

The Joint Task Force mission that started with the State Department request for humanitarian assistance ended with little or no fanfare. The holiday season was approaching quickly and, although those stationed in Guyana during Thanksgiving in 1978 had little to be thankful for, they were still headed home in time for Christmas, Chanukah and New Year’s Eve. By December, the State Department briefings quickly shifted to other concerns dominating the waning days of 1978.

To date, there has been only one eyewitness account of the military’s role in Guyana. Jeff Brailey’s book, The Ghosts of November, is sadly out of print and only represents a fraction of the efforts undertaken in Guyana. Most members of the Task Force have yet to talk openly about what they saw, what they did and how it may have changed them. Before Jonestown slips from memory into the realm of history, the story of those who served in Guyana needs to be documented, recounted and remembered.

(Chris Knight-Griffin welcomes all contacts from anyone involved with this operation, especially the personnel who actually did the hard work in Jonestown or Georgetown, Guyana, or Dover, Delaware as a part of the Joint Task Force. All communications will be kept confidential. He may be reached at jonestownresearch@hotmail.com.

(Mr. Knight-Griffin is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His other articles in this year’s edition are What The Military Didn’t Do: Debunking One Conspiracy Theory and FOIA Tapes Show U.S. Embassy Knowledge, Confusion During Ryan Trip. His complete set of articles for this site is here.)

Notes

[1] Some early press reports of the event stated that the human remains transfer cases were loaded in Jonestown. This is not correct. The transfer cases never left Timehri International Airport in Georgetown.

[2] The number of transfer cases in the official record varies from a mission maximum of 81 cases, to 83 in after action reports, SITREPS and personal accounts.

[3] The record indicates “one H-21” yet this is in error since the H-21 helicopter was retired from service in 1967. It is assumed to be a typo and the correct aircraft is the U-21 Beechcraft King Air.