I would likely never have visited Richmond, Indiana, had it not been for a very special occasion: the 65th birthday of my dear friend Michael Klingman, a comrade from Peoples Temple. Mike had returned to Richmond from San Francisco six years earlier to take care of his partially paralyzed mom, Kathryn, following the sudden death of his step-dad.

I would likely never have visited Richmond, Indiana, had it not been for a very special occasion: the 65th birthday of my dear friend Michael Klingman, a comrade from Peoples Temple. Mike had returned to Richmond from San Francisco six years earlier to take care of his partially paralyzed mom, Kathryn, following the sudden death of his step-dad.

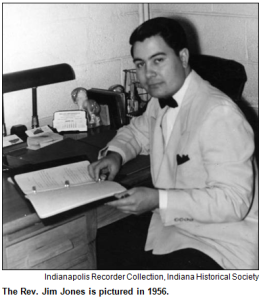

Richmond holds a unique place both in Peoples Temple history and for the Klingman family. It’s Mike’s hometown. It’s where Jim Jones and Marceline Baldwin met. It is also where, on Sunday, June 12, 1949, Jim and Marceline got married in a double ceremony with Eloise Baldwin, Marceline’s sister, and Dale Klingman, Mike’s uncle. All that I knew before I made this journey.

Mike drives me slowly down the narrow street in a rundown working class district on the northwest side of town, victim of extensive plant closures. We pass what is now a shabby Pentecostal church where Jim and Marceline’s nuptials had taken place a year after my friend was born. The streets and most of the houses look beaten up now, certainly could benefit from a fresh paint job. It’s a neighborhood that, according to Mike, was much more prosperous when he was young, before the working/middle-class in Richmond and throughout the upper Midwest was devastated by the export of jobs to third and fourth world countries to make profits for an increasingly tiny parasitic elite who are as likely as not to park their earnings in offshore bank accounts. The working families which remain were left destitute of good strong unions that could flex real power and organize an adequate defense. Mike recalls the good times growing up: hanging out on the porch or playing in the yard of his Uncle Dale and Aunt Eloise five doors down the street from what had then been the solidly-respectable and well-maintained Trinity United Methodist Church.

Though I haven’t come to Richmond to research the background of Jim Jones or his wife, the opportunity is one I have no intention of overlooking. After all, the small city of 40,000 and seat of Wayne County can give me some real idea of the cultural environment in which our former savior and his wife became adults.

Walking is my meditation. When I get to a new place, I want to wander around and get the feel. And so on my first afternoon while Mike is occupied elsewhere, I park my car around the corner from the ostentatiously unpretentious Friends Meeting House on the west side of town, a location where my rented car might be safe. Just out of sight beyond it is Earlham College, one of the foremost Quaker colleges on earth. The Society of Friends had its own great impact on me when I was a young activist looking for guidance. By apparent synchronicity, I was reading the journals of George Fox, its founder, when I first met Jim Jones. I decide, nevertheless, to wander in the other direction, perhaps because I had in fact also taken a very different direction in my life.

The streets among which I meander on this hot late spring afternoon are covered by just as many leafy canopies as those in the wealthier neighborhoods. But here something is markedly different. I see too many poor people to feel comfortable with myself or with the consumer values of the society in which we live. The people I pass have no market value. They are expendable in this capitalist system. Though there is a sizeable black community in Richmond, most of these are Caucasian. According to Mike, a large number are refugees or offspring of refugees from nearby Appalachia. Largely overweight and out-of-shape, some stand on porches drinking soft drinks or beer in the heat, dressed in clothes that are faded and, if torn, unrepaired. Others walk slowly back and forth in front of shabby residences or stare endlessly into space. There are no jobs that pay enough to enable these people to live decently and retain a vestige of hope based on self-respect. There is hardly any safety net left either, especially in this Tea Party heartland.

The shadows of the destitute and near-destitute crowd the supposedly rehabilitated old downtown. Some survive as renters in slowly crumbling brick homes, subdivided into apartments, that were built before or shortly after the Civil War. I wonder how many are actually homeless. Their lives – or walking deaths – can be traced to the inequality that has become a hallmark of our postmodern, possibly post-human society, especially evident in a place like Richmond. Once a hub of commerce, a thriving creature of the convergence of agriculture and industry in the second industrial revolution of the late nineteenth century, it is now one of hundreds of cities large and small that have been left behind in one of the many rust belts encircling our brutally ravaged planet.

Forced to fend for themselves, these poor people must indeed be shameless to survive. They must steal, sell their bodies, deal and/or do legal and illegal drugs, risk their lives to sleep unprotected in the open. Many of the males are veterans of our endless foreign wars. How many of them receive most of their welfare in the form of jail time? I don’t have to ask what Jim or Marceline Jones would think. I see all the well-kept churches like Reid Memorial Presbyterian, almost empty except for the Sabbath and choir rehearsal, with their fine steeples and stained-glass windows lining North A Street and other avenues. Such venerable institutions could really help people like these who are without means, but a serious mission of service would require adhering to the bold headline ethical mandates of Jesus that demand so much as to be scandalous. In subsequent days it becomes clear to me that some of these people are active members of the working poor: cashiers in strip mall chains, preparers and servers of fast foods, jobs that pay no more than the dismally-depressed minimum wage. Encountering them in their defenselessness opens my heart in a way nothing else here does, but it makes me feel restless too, wanting to do something I don’t even know how to think about quite yet.

Though I vaguely knew that Richmond and the area around it had been one area of Quaker settlement, I don’t realize, until my modest research in the well-provisioned public library, that it was the area of the most intense Quaker settlement west of the Appalachians. Most of the settlers arrived here as refugees from the Piedmont of slave-holding North Carolina, moving along what subsequently came to be known as The Quaker Trace. At one time the Richmond Meeting had, in fact, superintended the development of every other meeting to its west – all the way to the Pacific. Together with its environs, it retains the highest concentration of Quakers outside the City of Brotherly Love.

What puzzles me is that Jones never said anything about Quakers, their role as the original movers and shakers of the Abolitionist movement, or their steadfast refusal to make war on other human beings. He did strongly support the race of the Marin Quaker, Phil Drath, for the Democratic nomination to Congress in the spring of 1966, but he didn’t identify the candidate’s Quakerism as a reason for the support that he – and therefore we – gave. Such silence seems strange from a man who gave his eldest biological child the middle name of “Gandhi,” after the leader of India’s non-violent independence movement against Great Britain whose own philosophy converged with that of the Society of Friends.

Something is obviously not quite right here. When I ask Mike what he thinks of Jim’s silence on all matters Quaker, he confirms what I suspected: that the young, marginal but struggling Jim perceived Quakers of all sorts as much too comfortable and self-righteous to be companions in an uprising of the underprivileged against those who hold or have legally stolen the overwhelming proportion of resources. The young Jim Jones certainly had ample opportunity to observe local Friends. Tim Reiterman’s investigations show that Jim occasionally, perhaps repeatedly, attended services in the local Quaker church.

However, that is only part of the explanation. What is most significant is that Jim’s own dad came from a firmly-established Quaker family in Lynn. James Thurman Jones may still have identified as a Quaker, despite the military service he’d performed during World War I in violation of the tenets of his faith and his absence from services, and his disabling war injuries may have been the punishment he felt he deserved. A very wise and inquisitive child, Jim Jones may have reasoned, however, that he and his mother didn’t deserve to live in near poverty as a result. As he grew to manhood, his study of history and politics must also have made him realize that his father had done little more than provide cannon fodder for the Wall Street bankers who wanted their war loans repaid by a victorious Britain, not cancelled by a Deutschland Über Alles.

As I drive north on State Highway 27, a two-lane road that leads through Richmond to Lynn, sixteen miles to the north where Jim Jones grew up, I now recognize that I’m following the same Quaker Trace which in turn became the pre-eminent route of the Underground Railroad in Indiana. Knowing more of Jim Jones’ childhood history, I begin to understand why he might have tried to overlook or at least to play down the significance of Levi Coffin, the courageous Quaker whose home, long since turned into a museum, sits flagrantly on the main street at the hub of tiny Fountain City, midway between Richmond and Lynn. Through the windows of the museum, I can see photos of some of the places in which hundreds of runaway slaves had been hidden on their way north, following the North Star which is to this day emblazoned in red over the thresholds of as many homes along the route as display the stars and stripes, indicating an enduring pride in the faith that had supported the steady exodus of slaves into at least a semblance of freedom.

Coffin himself was a real organizer, willing to disobey any law if conscience dictated. He later moved to Cincinnati where he coordinated a network of suppliers and producers around the nation that provided goods guaranteed to have been made by free men and women, comparable to the Fair Trade movement today. If Jones did know anything about Coffin or the importance of his Quaker faith, or the conjunction of that religious tradition with the anti-slavery movement in the hated small-town countryside where he grew to stunted manhood, he never even hinted of it in my hearing.

I enter Lynn – population slightly over 1,000 – for the first and possibly last time early in the afternoon of a mid-May Saturday, 2013. From a modest distance I can see a small carousel. People of all ages are heading on the sidewalk towards some sort of festival taking place in the heart of this ordinarily sleepy village. Hesitation competes with curiosity within me: this was the hometown of the man who gave my life meaning and betrayed my trust. Feeling somewhat haunted even at midday, I park right in front of the Quaker Church, the first sizeable building I encounter where once again my car at least can feel protected from chaotic elements of society, if not the equivalent parts of my mind.

Getting out of the car, I stretch, breathe deeply and look at the church. Yes, this is a real church and not a meeting house. The large sign in front makes that and a few other matters clear. While Richmond Friends, presumably more sophisticated, retain the antique but democratic form of worship in which there’s no preacher except for the light – sometimes blinding, often not – which one receives by waiting in the company of others, out here in the country. Quakers appear to want at least one pastor to guide their consciences. In this case there seem to be two, the heavies among equals. Like every other officially friendly edifice I encounter on my journey, the outside is spotless and borderline colorless, enhanced by the conventional lawn-dominated garden which keeps nature well within bounds and discourages potentially disorderly life forms from entering. While I don’t search too hard, I find nobody else hanging around. I wonder, nonetheless, who the congregants are, what role they play in the workings of this small, probably insular community, where relationships of every sort acquire an intimacy that may be casual but is foreign to most cities. I wonder what role, if any, they played in the life of the marginal kid whom Jim Jones must have been, known as the son of a lapsed Friend. From his position as a more-than-half outsider, a stranger to ways that privileged silence over rhetoric, how could he have felt truly welcome?

Lynn really does seem to be enjoying a much-needed holiday, the excuse for which I never quite find out. The festival has certainly brought townsfolk together. I can hear a barker in the distance selling tickets. A community luncheon is well in progress at the Fire Department. Every other dwelling seems to be hosting a garage sale, each one an excuse for neighborly gossip.

Once I get beyond the social busyness of the first block, I make an arbitrary left turn and almost instantly face the side of an abandoned one-story cottage. On the door of it somebody has written in bold blood red letters: “GET THE NIGGERS!” These are words that cut like knives, that have hung human beings from trees. Though I’ve seen photos of much worse – many taken in American South or in Africa – I’ve never directly faced such an obscenity myself, an exercise in the ugliest form of free speech. Having once seen it, I start looking for any sign of black folk, even as I wonder who among them would dare to live in a community that tolerates such a symptom of lingering brutality? Later I scan the crowd at the carnival. All the faces I see this afternoon are white, ruddy, pale, pink, yellow, and tanned. Definitely not black. What are these people afraid of? I still wonder. Who of them are vigorous, flag worshipping racists for whom Jesus is the Supreme Warrior? Who disguise the fear and loathing masking their guilt by keeping a distance that is close to absolute from the shadowy other? Are these people afraid of the ghost of James Warren Jones too? I trust that Friends at least have found some way to peacefully coexist with the fascists in their midst without stepping on too many toes.

Minutes later, my spirits are lifted. A male voice shouts appreciatively from a car pulling into a parking space: “Like your hat.” My red felt hat with wide brim is a signature piece that Mike gave me as a present years ago, and I’m always cheered when someone appreciates it. I turn towards the source, a slightly long-haired, somewhat heavy set teenager. His smile is broad. Sitting beside him is a striking long-black haired woman, possibly in her late fifties. Her face, though gnarled, exhibits beautiful bone structure. Could she be part Native American? Is she his mother or, more likely, grandmother? She’s smiling too. Of course I stop and smile right back. We start talking. Without hesitation I tell them that I’m a survivor/defector from Peoples Temple, that I’ve come here to explore. Do either of them have any idea where Jim Jones might have grown up? Studying me with keen but kind eyes, the woman responds in a manner that trusts my intent.

“He grew up in a place that’s been torn down. It was out just beyond the edge of town. You can still get there if you turn left at the east/west highway just north of here.” She points to what seems the northwest, then continues: “My grandmother used to take care of Jim when he was a baby.” I note that she refers to him by his nickname as if he were a familiar, still part of the community after all the decades that have passed. There is no hint of hostility, though perhaps of irony in the tone. Neither of them seems to be uncomfortable talking with me about the man who gave their village its uncoveted reputation as the Nazareth of a psychopath. “You’ve heard the stories,” she says. “He was a wild one.” Then she adds, “A lot of the stories are true.” She refers to his escapades, his experiments to manipulate other kids into doing what they didn’t want to, his collection of stray animals. I hear no judgment in her words, just a casual summary of the much too obvious warnings that were recognized only after it was much too late to have any impact on the outcome.

“Where you really need to go is Crete,” the woman advises. “That’s where he was actually born. Don’t worry, it’s not far. It’s easy to find. You drive just north of town to the same junction, but turn right instead, head east towards Ohio. Just before you reach the state line, maybe four miles, you’ll see a sign. Take the county road, the Arba Pike, south. It’s about a mile, maybe a mile and a half from there. There are only a couple of houses left. Go see for yourself.”

The precious map I carry in the glove compartment tells me that Crete is within a mile of the highest point in the whole flat state of Indiana from which undoubtedly there’s no real view. The place itself is pretty much a ghost town now. The two remaining houses, both still occupied, face each other across a bend in the winding, ever so suggestively hilly road. An empty bathtub sits on the front porch of one. The dwelling across the road still bears the North Star of the great cause of abolition, emancipation, opportunity to become a full person entitled to hope.

Crete doesn’t make me think of Knossos, the ruined palace of its ancient ocean empire with its few remaining columns only able to hold up fantasies. But it does make me think of its infamous labyrinth from which the hero Theseus managed to emerge, having killed the bull called the Minotaur. The name makes me think of Lynetta, Jim’s mother, of the occasions on which she told me the mythical prophecies she received of Jim’s birth, including one that involved something like a labyrinth, perhaps its antecedent, the underground bridge by which Osiris rose from the dead.

The soil of south central Indiana is rich, still fertile despite all the crimes that have been inflicted on it with toxic fertilizers and genetically modified seeds. The climate, though volatile, avidly supports life throughout most of this region. I can only imagine how densely forested it was when the National Road was built, starting in Richmond, before Indiana had become a state. There is no reason anyone should end up poor in this environment which is infinitely more conducive to life than all but the slim northwest corner of my own state of California where desert megalopolises are becoming more unsustainable every day. If a saner culture had shaped us to be nourishers of life rather than trained or untrained killers, living in fear of all those anonymous others whom we have robbed of their birthrights, most people would be fleeing the cities, learning to farm again other than as a romantic hippie fantasy, producing what we all need here at home rather than working as drones for faceless corporations which are rapidly destroying the ability of our planet to sustain life. We would be building public infrastructure, not selling off our schools to the highest bidder and piling debt onto students so they will be desperate enough to do whatever they’re told.

Richmond would then be a perfectly necessary country town to which farmers working in cooperatives would flock, just as they did when they made possible the second industrial revolution. It’s already two-fifths the size of Athens in the Age of Pericles, half the size of Florence when Lorenzo the Magnificent patronized any god who could paint, about the size of Boston and much larger than nearby Concord where Emerson conspired with those at outlying Brook Farm and Thoreau remained cloistered, allergic to society. Who knows what scientists, artists, and teachers could come out of such an economically and spiritually revitalized urban hub as Richmond in a transformed culture based not just on respect for individual liberty but on pursuit of the common good through democratic ownership and management of the economy? Such an accomplishment will require the ongoing miracle of people all over the country becoming aware of both the desperate state in which we find ourselves as well as of our potential power as citizens and workers to transform the machinery of production to serve the cooperative needs of all the people and not just the greed of a financial elite from whom we need to reclaim our commons.

When I ask myself why Peoples Temple ended up the way it did at Jonestown, I also have to pose the following: Is the United States ending up as an equally botched and hypocritical experiment in the creation of a just society? The difference, unfortunately for those of us who survive – and there are more than seven billion folks currently being surveilled and policed in the name of democracy and freedom – is scale. The reach of biracial President Obama as global enforcer for the corporate criminals who hired him is potentially thermonuclear. So is that of his cornered dog opponent, Russian President Vladimir Putin, iron hand in velvet boxing glove, recalling too many past, often surprise invasions. Forgetting for the moment such relatively unimportant matters as the niceties of constitutional law, and international conventions that prohibit even the threat of force, let us consider the historical outcome of imperial hubris and the role of the individual in the dynamics of social pathology. Let us look at the failures of these leaders whom we have chosen us to lead us, not just the failure of Jim Jones who took a mere thousand to their totally unnecessary deaths.

What’s not to abhor about the celebrity narcissists whose idea of presidential legacy is the depraving megabucks to be made selling obese books like “Giving” that should embarrass any mere sociopath? What have we come to in this façade of civilization when psychopathology has become the new normal? All the while, climate catastrophe begins to explain to us the hideous emerging reality, and Fukushima continues to leak. The thrill of capitalism is gone. A race to the bottom it is as it always was, pitting carnivore against carnivore, in an orgy of vacuous acquisitiveness, turning the potential heaven this earth might be into a hell, as Michael T. Klare outlines so brilliantly in his new book, The Race for What’s Left: The Global Struggle for the World’s Last Resources. The love of what money can buy was diabolical when Jesus chased the moneychangers out of the Temple and was in consequence crucified. Now the capitalist system is in the process of self-destructing and taking with it, not only the rainbow of luxury goods we never really could afford, but the people who have piled up the debts to nature. Forget chemical weapons in Syria or alleged nuclear weapons being developed by Iran. Planetary degradation is our real legacy as a species to whoever is so unlucky as to succeed us in the role of stewardship. In the meantime, what capitalist economists dismiss as mere “externalities” are sealing our fates.

Will anyone remember the trillions of life forms inhabiting this planet, one of which calls itself human, much less Jim Jones, Peoples Temple, and Jonestown? It is our job nevertheless to give an accounting. This is a small part of mine. One never knows what might happen.

(Garrett Lambrev is a frequent contributor to the jonestown report. His other articles in this edition are The Tale of the Tape, Joe Phillips: A Reflection, and Youth Theatre Makes Peoples Temple Breathe Again. His previous writings may be found here. He can be reached at garrett1926@comcast.net .)