“I think they’ve been drinking the Kool-Aid…” What image just came to your mind?

Minor-scale miscommunication happens around me all the time. My working world and domestic world are diverse, highly populated and interactive places. I find I can be speaking at cross-purposes with someone when we get too informal or colloquial. That doesn’t stop us – it’s usually fun, and not hurtful, but now and again we realize we are not all on the same page. We have to check in with each other, and clarify.

“Whoa, you’ve totally been drinking their Kool-Aid, haven’t you?” When someone uses this phrase in my hearing, I used to try to guess from context which image they were trying to evoke. Now, instead of guessing, I follow up and ask what they mean by that. Context is everything. And it can be very complex.

Visitors to this website – and especially those who read the jonestown report‘s annual directory of “drinking the Kool-Aid” references – can’t help but visualize the vat of poisoned punch whenever they hear the phrase. In fact, not much imagination is necessary, as the image was graphically burnt onto the national consciousness through an iconic photograph as the story broke late in 1978, and today the image is still instantly available on the internet. If that is your main context, there is still a question: what is meant today by “drinking the Kool-Aid”? If Jonestown was the origin of this phrase, then why wasn’t Flavor Aid[1] made part of this expression?

I would like to talk about “Kool-Aid” images that were equally well-embedded in American culture prior to 1978. I think that the origin of the phrase “drinking the Kool-Aid” doesn’t come from a single point in history, but from a building up of images that associate, merge, disassociate, and recombine both in the media and independently within all the minds in the nation, bouncing in and out of shared and personal spaces and continually changing.

In his 2004 book, Don’t Think of an Elephant!, George Lakoff makes the case that we frame our discussions in American politics through commonly-held images, which may polarize us and limit discussion when it comes to important issues. If someone tells you not to think of an elephant, Lakoff says, it’s already too late: the word “elephant” alone evokes the image of the animal in your mind, so that you can’t actually obey the command not to think of one. As an example of how framing with images can impact politics, he points out that Nixon famously paired himself with the image of a crook in the national consciousness when he said, “I am not a crook.”[2]

I am going to give you a phrase; if you know it, it should summon a picture in your mind just as easily as “elephant” does. Here it is:

“Hey, Kool-Aid!”

Did you just think of a curvy glass pitcher with a smiley face on it? Possibly in black and white on a kitchen table, or maybe as a colorful figure bursting through a wall to save thirsty kids? Kool-Aid TV commercials were heavily produced during the General Foods ownership of the brand from the 1950’s through to the 1990’s, and each commercial was repeated many times. Many of them are still only a few mouse clicks away on YouTube. As a result, this is an image that was much with America before, during, and after the point when the image of the end of the Jonestown community entered the mix via newspapers, television, and magazines (and later, books, documentaries, and the internet).

Have you ever called a photocopy a “xerox”? Have you ever called a facial tissue a “kleenex”? In Texas, soft drinks are often called “coke,” even when they are actually Pepsi brand, or not a cola at all. This is the result of highly successful branding by marketers. The brand Kool-Aid could be considered strong enough to trump other brands and become synonymous with artificial fruit drink or punch. If Flavor Aid and Kool-Aid had reversed their distribution and marketing strategies, perhaps we might have off-handedly called a brightly-colored drink made from powder “flavor aid” instead. But as it is, “Kool-Aid” may well be a specific brand name, but for some people, it is also a general product term.

If you begin with Jonestown as your personal context – your strongest point of reference – then any reference to the Flavor Aid we know was drunk there as “Kool-Aid” can be viewed as an error. If you begin with a personal history of calling 7-Up “coke,” a Puff’s tissue “kleenex,” and punch “Kool-Aid,” then you might not see much of a distinction. “Kool-Aid” would be interchangeable with Flavor Aid, Hawaiian Punch, or any other artificial fruit drink. Not an error, and no insensitivity intended. Just successful branding.

* * * * *

There is another place in cultural history where this casual brand-name use might have come into play. I don’t know that anyone ever did the research on it thoroughly, because it probably didn’t matter in this context. Articulated in 1968, however, it had a ten-year head start to grow the imagery around “Kool-Aid” in America before Jonestown’s image was added in. Once again, I’ll provide the phrase and you provide the image in your mind:

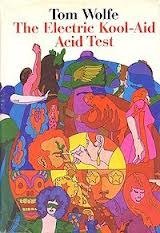

“Electric Kool-Aid”

Did you perhaps see the cover of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, the book by Tom Wolfe, first published in 1968? Or maybe you recalled one of the many photographs taken of the theatrical events of the LSD era? Perhaps you were even on the scene in 1966-69, and can recall getting LSD-spiked punch from a baby’s bathtub at the January 1966 Trips Festival.[3] Regardless, these images did not fade quickly with time, either. Tom Wolfe’s most recent novel, Back to Blood, is out, and when I saw it on the bookshelf of my local bookstore this summer, it was right next to a brand-new copy of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, still in print. A Merry Prankster film was released in 2011, and there have been documentaries and many books in the intervening years, as well.

Did you perhaps see the cover of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, the book by Tom Wolfe, first published in 1968? Or maybe you recalled one of the many photographs taken of the theatrical events of the LSD era? Perhaps you were even on the scene in 1966-69, and can recall getting LSD-spiked punch from a baby’s bathtub at the January 1966 Trips Festival.[3] Regardless, these images did not fade quickly with time, either. Tom Wolfe’s most recent novel, Back to Blood, is out, and when I saw it on the bookshelf of my local bookstore this summer, it was right next to a brand-new copy of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, still in print. A Merry Prankster film was released in 2011, and there have been documentaries and many books in the intervening years, as well.

Did Tom Wolfe casually or deliberately use “Kool-Aid”? Did the people he interviewed know what they were really drinking? Evidently not, in the case of Clair Brush, who didn’t see what they mixed in the trash cans, not the brand of powder, and not the LSD:

…then a large trash can, plastic, was carried to the middle of the room, and all were invited to help themselves to the Kool-Aid it contained. There was no big rush to the refreshment stand…people wandered up, it was being served in paper cups, and since Kool-Aid is a staple in the homes of Del Close and Hugh Romney and other friends of mine, I thought it was quite a natural thing to serve.[4]

Brush was at the 1966 Watts Acid Test, on assignment for the Free Press. There were actually two trash cans of fruit punch there that night (“This one over here is for the little folk and this one over here is for the big folk. This one over here is for the kittens and this one over here is for the tigers.”[5]) Likely she disregarded the two cans as meaning two different drinks, and saw it as a measure for making sure there was enough refreshment to go around, because she simply couldn’t hear Romney’s voice over the microphone clearly enough to get the message that this was a test. Instead, she experienced the Merry Pranksters public prank full-on: she had no idea, and drank indiscriminately amidst a very theatrical crowd of people.[6] Trippin’ on LSD. Crazy!

Before 1978, you could drink “Kool-Aid” because it was a random cup of artificial fruit punch. Or you could trip – drink the “Electric Kool-Aid,” as Romney called it.[7] So far, no one has documented a solid example of “drink the Kool-Aid” used as a metaphor in writing or other recorded media prior to November 18, 1978. If any such instance can be found, that would indicate an earlier, clearly intact, origin for the phrase. A (somewhat) safer origin, one that would be less sinister, more light-hearted, at least – those crazy [trippin’] Kool-Aid [LSD punch] drinkers, they’d believe anything!

But wait. It was actually Flavor Aid and cyanide at Jonestown. At its inception, “drink the Kool-Aid” was a phrase already not 100% about Jonestown, no matter who first said it, even if they included key contextual words like “vat.” “Drinking the Kool-Aid” had branding influence built into it right from the start simply because it contained the brand-name “Kool-Aid.” Branding success aside, would a similar phrase ever even have been coined without the Pranksters and Tom Wolfe’s book to market their story? What is clear is that Jonestown added to a context that already existed, expanding it.

Dictionaries can be compiled as prescriptive references or descriptive ones, or a bit of both. If you want to preserve a word unchanging, you can try to prescribe its use: this is the origin, this is what is it supposed to refer to, this is how it is pronounced. Some cultures – the French come to mind – attempt to do this firmly. However, if you are describing how word use changes with time (as it inevitably does, rapidly or slowly), you might put in origins, possibly indicating some definitions as “archaic,” while indicating more current meanings in additional definitions. Before you set down a descriptive definition, it might help to systematically collect anecdotal evidence to be sure you were reflecting true contemporary usage.

Dr. Phyllis A. Gardner has gone to the trouble to ask students what “drinking the Kool-Aid” means when she teaches:

One problem in keeping the torch of research alive is that thirty years have passed. When I talk about Jonestown in my psychology and sociology classes, they don’t know what I’m talking about. On the other hand, just for anecdotal argument, I also poll my classes from time to time, asking them what they think of when they hear the term “drinking the Kool-Aid.” Overwhelmingly they say, “crazy.”[8]

“Crazy” doesn’t point in any single direction, but this casual anecdotal research does show some close parallels between the LSD and cyanide contexts. Post-1966 “Kool-Aid” has pranksters in it, and pranksters were “Day-Glo crazies”:[9] crazy clothes, painting, music, behavior, drugs. Not only that, The Merry Pranksters had a leader in Ken Kesey.[10] He could determine if you were “on the bus” or “off the bus”; there was a literal bus, but there was also a powerful social sense: Kesey could determine if you would continue to be included in his communal living arrangement and/or be considered a Prankster.[11]

Fast-forward 10-plus years, and add the Jonestown images to “Kool-Aid.” Edith Roller kept regularly-updated journals that document how Jim Jones used inclusiveness to manage his community. Roller wrote of a preparation exercise she participated in fully nine months before the Jonestown community chose revolutionary suicide. Jones prepared a punch “potion” for the group:

At length Jim stated that the political situation showed no signs of clearing up and that we had no alternative but revolutionary suicide. He had already given instructions to make the necessary arrangements. All would be given a potion, juice combined with a potent poison. After taking it, we would die painlessly in about 45 minutes… [12]

After most people had drunk their cup, Jones revealed it was only punch with “something a little stronger in it.” In her February 16, 1978, journal entry, Roller wrote about how she had felt while waiting for her cup, and about how the outcome would look to others:

I gave some thought to my sisters and Lor. When they heard the news I was afraid they would think Jim Jones was a lunatic and I wasn’t much better than one. This thought I dismissed. What did it matter? Sooner or later when the bomb fell, they would realize Jim Jones was right as I had always said.[13]

Purple punch: don’t think of Kool-Aid! Kool-Aid: don’t think of acid! Kool-Aid: don’t think of Jonestown!

Punch in a washtub. Lunatic. Punch in a trash can. Crazy. Are drinkers crazy because they are willing to drink a cup, or because they what they drank made them crazy? If LSD was thought to be safe, and was associated with healing, the contexts of LSD punch and cyanide punch would not be so easy to merge. As it stands in America, LSD is deemed dangerous as recreation and not medically useful to the point of being made illegal as of 1970. While some may debate the validity of the reasoning behind this decision, it is a federal law. On the other hand, no one has any doubts of what cyanide can do. Punch in a trash can. Punch in a washtub. Which is the most dangerous one? The potion in the vat. But that still doesn’t fully answer the question.

Unless we clarify amongst ourselves, we may speak at cross-purposes. Among the collection of Kool-Aid articles on this website, Kathy (Tropp) Barbour’s Coming to Terms with “Drinking the Kool-Aid”[14] may be the most compassionate. She acknowledges that the phrase has been hurtful, showing insensitivity and lack of respect for the surviving loved ones of the individuals who died in Jonestown, but she stresses it need not be that way. She is correct. The phrase is indelible, having worked its way into the fabric of American culture, but there it has joined a collection of meanings and softened and changed. By making no assumptions about the context of “drinking the Kool-Aid” when used within your hearing, you have an opportunity, as she says, to “overturn the vat”[15]; you may discover a broader context, or can create one.

The Jonestown story does not remain isolated from other cultural events and influences – a healing reminder that the isolation of Jonestown was not total, and that some survived for precisely that reason. The community that allows other communities to flow through it, connect and coincide with it, and allows transparency in its dealings with its members, is best empowered to correct course as needed, and to remain as beautiful and healthy as those who created Jonestown strived to be.

(ieva swanson is an experienced corporate trainer with a B.A. in Cultural Anthropology and Linguistics & Semiotics from Rice University. She adds, “My personal connection to Jonestown is only that the events of that terrible day became part of my America.”)

Endnotes

[1] “One of the surviving eye witnesses, Odell Rhodes, recalled that two nurses brought out the vat of Flavor-Aid and cyanide.” From Nora Woods, “Jonestown as a Reflection of American Society”.

[2] George Lakoff, Don’t Think of an Elephant! (White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2004), 3.

[3] Charles Perry, The Haight-Ashbury (New York: Vintage Books, 1984; New York: Wenner Media [paperback edition], 2005), 41.

[4] Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1968; New York: Bantam [paperback edition], 1989), 244.

[5] Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, 244.

[6] Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, 244.

[7] Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, 244.

[8] Phyllis Abel Gardner, “What Does Kool-Aid Really Mean?”

[9] Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, 197.

[10] Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, 55.

[11] Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, 74.

[12] Edith Roller Journals, February 16 entry

[13] Edith Roller Journals, February 16 entry

[14] Kathy (Tropp) Barbour, Coming to Terms with “Drinking the Kool-Aid”

[15] Barbour, Coming to Terms with “Drinking the Kool-Aid”