Richard Tropp was a follower of Jim Jones and a victim of the Jonestown suicides. As he was dying, he wrote a remarkable letter, The Last Words of Richard Tropp, which I discovered while doing research for my multimedia novel Reconstructing Mayakovsky.

Richard Tropp was a follower of Jim Jones and a victim of the Jonestown suicides. As he was dying, he wrote a remarkable letter, The Last Words of Richard Tropp, which I discovered while doing research for my multimedia novel Reconstructing Mayakovsky.

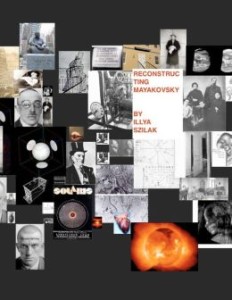

Published on the Internet in 2008, and included in the second Electronic Literature Collection, Reconstructing Mayakovsky uses text, image, sound, video and hyperlink to tell the story of Vladimir Mayakovsky, the avant-garde poet who, disillusioned by the Stalinist crackdown on artists and writers, killed himself in 1930 at the age of 36. For me, Tropp’s sincere but ultimately futile desire for a world in which Jones’ “ideals of brotherhood, justice and equality” would be realized, resonates deeply with Mayakovsky’s failed dream of a Communist utopia.

Reconstructing Mayakovsky imagines a post-apocalyptic dystopia in which uncertainty and tragedy have finally been eliminated through technology. As readers discover Mayakovsky’s page-turning biography (prison at age 15 for revolutionary activities, a lifelong affair with his editor’s wife, infamy as a Futurist poet, participation in the revolution, fall into disgrace, suicide, and posthumous resurrection by Joseph Stalin), they explore their own fears and fantasies about the future.

The novel does not consist of a single text, but rather as a series of “mechanisms” that present the same information in different formats. These include a hand-drawn animation, a fake investment video, an audio soundscape, a manifesto, proposals for performance art, Mechanism B (a concrete poetry engine), and a virtual archive. Tropp’s letter is included in the archive.

Clicking on the tile that contains the link to Tropp’s letter, the reader will notice tags at the bottom. I use both traditional tags, in this case “violence” and “utopia” and what I think of as “Anti-Google” tags. Tags such as “Elegy for Dreams Deferred” and “Final Number” defy and evade algorithmic categorization. As the reader clicks on any given tile, others with the same tag will light up – revealing the networked quality of information. At the same time, every tile is linked to a single, dominant narrative, i.e. the novel itself. No matter where the reader is on the site, she is only a single click away from the unifying story. In this way, the archive – like Mayakovsky’s life and poetry – embodies the conflict between a dominant, fixed narrative (the end of history propounded by the Soviet State) and a revolutionary, iconoclastic artistic vision.

I began to work on Reconstructing Mayakovsky shortly after the events of 9/11 when fear and a desire for security seemed to override many Americans’ commitment to freedom. Happening upon an article about the poet, I became obsessed: I bought every obscure, out-of-print book that I could find, I hired someone to teach me Russian, and I began to write, not a straight historical novel about his life, but a sci-fi inspired one in which Mayakovsky is resurrected from death through his own, mine and other people’s words.

One of my primary concerns in writing Reconstructing Mayakovsky was to explore the power of poetic language to expand meaning beyond the “official” definition of words, and to confront the misinterpretation that such an opening up inevitably incurs.

In my story, an artificial intelligence called “The Oracle” interfaces with the neural networks of all citizens of the dystopian OnewOrld, reading their thoughts and transforming their speech into a universally intelligible language called OnewOrd. Moreover, because all data feeds through it, it has “perfect” information, and is able to predict the future. The computer, however, refuses to use OnewOrd. Instead, it communicates its predictions through poetic ciphers: appropriated bits of data that range from the lyrics to David Bowie’s “Moonage Daydream” to eyewitness accounts of the bombing of Nagasaki. In this way, the reader, herself, must decide what, if any, meaning there is.

This is how Richard Tropp fits in as well. Through the text of his final letter, he demonstrates his understanding of how we use stories to make sense of, and construct a framework for the masses of data that our brains process so that we can move into an uncertain future. As an English teacher, he realized the power and importance of language, and its limitations.

His letter begins:

Collect all the tapes, all the writing, all the history. The story of this movement, this action, must be examined over and over. It must be understood in all of its incredible dimensions. Words fail… We know there is no way that we can avoid misinterpretation.

Like the computer that refuses to use OnewOrd, Tropp agonizes over a loss of meaning. He is acutely aware that what makes language powerful – its elasticity and variability, is also its weakness. He grasps for the one “eternal” story among all the possibilities.

“Something must come of this. Beyond all the circumstances surrounding the immediate event, someone can perhaps find the symbolic, the eternal [cross-out] in this moment – the meaning of a people, a struggle – I wish I had time to put it all together, that I had done it. I did not do it. I failed to write the book.”

The interface for Reconstructing Mayakovsky, created in collaboration Cyril Tsiboulski and Cloudred Studio, purposefully destabilizes the idea of a timeless, individually authored masterwork. Constructed using mostly open source code, the website uses links rather than embedded data. Thus, errors can accumulate, readers may leave to view a YouTube video or another website and never return.

It has been 35 years, not even half a century, since 918 people lost their lives in Guyana. Ask any current high school student about it, and he will likely have never heard of it. The tragedy of Jonestown is not only the loss of lives, or that Jones’ vision was never realized; it is the fact of time passing. One epoch-defining story replaces another. Life goes on.

A tiny kitten sits next to me. Watching. A dog barks. The birds gather on the telephone wires. Let all the story of this People[s] Temple be told. Let all the books be opened. This sight …o terrible victory. How bitter that we did not, could not, that Jim Jones was crushed by a world that he didn’t make – how great the victory.

Richard Tropp is dying. At the end of his letter, amidst all the words, the dreams, the beautiful visions of the future, he acknowledges and bears witness to the living world too late.

When Reconstructing Mayakovsky was first published, the reader could perform a real-time Google-image search for what I call the “big words” – “truth,” “hope,” “freedom”. I loved the idea of imaging the truly unimaginable and having these “absolutes” change with whatever the online community was consuming at the time. The engine is now broken, like the 404 errors that have accumulated in the archive, it is a victim of time and “progress;” the technology no longer supports it.

As much as it pains me to see my creation die, it also gives me hope; for the truth is there is no final number. There is no eternal utopian future. There is only life and death. How we lead our fragile, ephemeral lives, embracing brotherhood, equality, justice, or not, is, in the end, the story that matters.

(Illya Szilak can be reached at iszilak@gmail.com.)