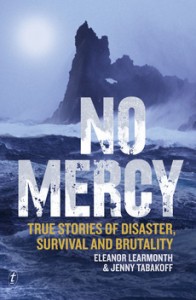

My co-author Jenny Tabakoff and I have just published our book No Mercy: True Stories of Disaster, Survival and Brutality which – although it doesn’t focus on Jonestown alone – considers its important place in examining human behaviour during times of extreme isolation. Using examples from history that range from the Roman siege of the city of Numantia in 134 BC to the trapped Chilean miners in 2010, we concentrated on groups that were stranded – cut off from outside society and conventional law and order – in light of what we call “the Lord of the Flies principle.” We focused especially on the factors that contribute to group collapse, such as fear, starvation, leadership issues, violence and so on. We also examined the twisted path of social disintegration. Does loyalty to the group have an inevitable use-by date? Are compassion and mercy expendable luxuries of civilization? Is the fragmentation of a group under stress inevitable and unstoppable? And how do some groups avoid the pitfalls and successfully work together, when so many others fail?

My co-author Jenny Tabakoff and I have just published our book No Mercy: True Stories of Disaster, Survival and Brutality which – although it doesn’t focus on Jonestown alone – considers its important place in examining human behaviour during times of extreme isolation. Using examples from history that range from the Roman siege of the city of Numantia in 134 BC to the trapped Chilean miners in 2010, we concentrated on groups that were stranded – cut off from outside society and conventional law and order – in light of what we call “the Lord of the Flies principle.” We focused especially on the factors that contribute to group collapse, such as fear, starvation, leadership issues, violence and so on. We also examined the twisted path of social disintegration. Does loyalty to the group have an inevitable use-by date? Are compassion and mercy expendable luxuries of civilization? Is the fragmentation of a group under stress inevitable and unstoppable? And how do some groups avoid the pitfalls and successfully work together, when so many others fail?

Although most of the groups we considered were stranded in the wake of disasters such as shipwrecks, we included Jonestown because its isolation – however self-imposed it may have been – demonstrated many of the same elements of social decay leading to its eventual collapse. The events of November 18 were so widely reported at the time and remain a vivid memory for many people. Jonestown illustrates that the threat of being in a group cut off from mainstream society is not merely of historical interest, but of real and present danger today.

In addition, unlike the vast majority of the castaway communities featured in No Mercy, Jonestown left a powerful visual legacy. While it is possible to imagine the streets of Numantia piled with corpses, it is quite another experience to see the devastating photos of the aftermath of Jonestown, particularly when they are contrasted with the Utopian promotional images taken earlier in 1978.

Most of the communities examined in No Mercy were entirely or overwhelmingly male: for instance, Adolphus Greely’s expedition (stranded and starving in the Arctic in the 1880s), or the drifting raft of the Medusa (on which 146 men slaughtered each other off the coast of the Senegal in 1815). Jonestown, however, was a mixed-gender group and we wanted to ask: would the influence of women alter the group chemistry? The answer: very little. Reading the words of Edith Roller in Jonestown, we were startled at the way she juxtaposed everyday banalities with casual ferocity. It’s almost as if an elderly neighbour had stopped talking about the roses and her bad back, and started discussing her plans for genocide.

We were also stuck by the similarities between Jonestown and the situation that developed on the remote Abrolhos Islands off the coast of Western Australia in 1629, when the Dutch ship Batavia wrecked and left over 200 people in the hands of a Machiavellian leader, Jeronimus Cornelisz.

Like Jim Jones, Cornelisz had a band of loyal enforcers and instigated a violent reign of terror on the men, women and children in his small community. Both men were intelligent, charismatic, given to quasi-religious delusions of power, and demonstrated sociopathic traits. On both the Abrolhos Islands and in Jonestown, the majority of the group fell victim – with surprisingly little resistance – to the minority power base. Also like the Jonestown community, many of the victims from the Batavia were ordinary people and families seeking a new start, and a better life, on the other side of the world.

Once the Batavia survivors found themselves isolated and trapped, the group dynamic spiralled downward, following a principle that one individual described as “man making his own law, with his own right arm.” Unfortunately for the victims, those right arms were holding pikes, cutlasses and knives. The only women to survive were those who had been forced into sexual slavery. Cornelisz personally ordered the murders of about 120 individuals, and justified his violence with a personal creed that he believed put himself and his followers beyond mortal judgment.

Take these proclamations by the two leaders:

For instance, in Patagonia in 1741, as Captain David Cheap struggled to stop mutiny by his 140 hungry, cold castaways from the shipwrecked Wager, he shot an unarmed man in the face. Cheap left him to die a slow, painful death in the middle of their camp as a warning to the others. Nevertheless, the majority of the men under the captain’s command soon rebelled because they perceived their greatest chance of survival lay elsewhere. This instinct for self-preservation seems to have been absent or suppressed inside Jonestown. Although we did not examine this in our book, we found it puzzling. Of course, it could be argued that Jones maintained control through sleep-deprivation, semi-starvation and violence. However, many survivor groups endured similar stresses, and most people, obeying our human hard-wiring to act in self-preservation, asserted themselves – with the result that the leader would quickly resort to even greater violence to maintain control.

There was another significant difference between Jonestown and the other groups we studied: it was the hardest one to come to terms with. We definitely saw worse behaviour in other groups, but somehow Jonestown was the most unfathomable. Was it because it is so recent? Was it the influence of the photographs, or the fact that I have a lot of American friends? All I know is that it still causes me to lie awake at night how it went so catastrophically wrong.

There is a fascinating psychological study waiting to be written on how the deep-rooted human drive for self-preservation was extinguished within Jonestown.

(Eleanor Learmonth has worked as a teacher and freelance journalist in Japan and Australia. More information on No Mercy: True Stories of Disaster, Survival and Brutality may be found here. She may be reached at sydbetts@iprimus.com.au.)