Working on a film about Jonestown – whether it is a documentary or a fictional drama much as mine – there are numerous elements to take into consideration, complicated by the sensitivity of the subject matter where the people involved have suffered tremendous loss and trauma. It was important to me to find a way to tell this story with the utmost respect in regards to the victims and their families. Each individual is different, with nuanced sensibilities, so there will naturally be some hurt feelings or objections to any film adaption. The challenge, as I knew from the start, is to reduce them, as much as possible while remaining true to the larger story.

Working on a film about Jonestown – whether it is a documentary or a fictional drama much as mine – there are numerous elements to take into consideration, complicated by the sensitivity of the subject matter where the people involved have suffered tremendous loss and trauma. It was important to me to find a way to tell this story with the utmost respect in regards to the victims and their families. Each individual is different, with nuanced sensibilities, so there will naturally be some hurt feelings or objections to any film adaption. The challenge, as I knew from the start, is to reduce them, as much as possible while remaining true to the larger story.

As I tried to emphasize in last year’s article, I entered this project aware of the possibility to offend, but I felt like there were lessons to gain and stories to share, so I spent a lot of time researching and developing this story, trying to find the right angle that had both the drama and cinematic gravitas that a film needs, as well as the empathy, understanding and respect that this true event deserves.

I knew right away that this project would not be a reenactment, but a fictional story, centered on the true events. Since we were working with the short film format, I needed something that would draw the audience immediately in and help them understand quickly what the story was about. I was very fascinated with the element of the congressional delegation arriving in Jonestown at a moment of great tension and conflict. We already know the final outcome, but we can find ourselves lost in the intervening events which shed light on the question: How did this end the way it did?

I centered the film on a reporter accompanying the congressman into Jonestown. In 22 minutes, the audience goes on the same journey as the protagonist, entering a community of peace, unity and justice, and slowing watching this illusion unravel.

Working with the actors, especially Jim Jones’ character, on this project was completely different from anything I’ve ever done before. Leandro Cano, who portrays Jim, had the daunting task to display the charisma, energy and ruthlessness that Jones inhabited. To play the truth of the character, we had to approach the man with no judgment and to find justification for what he did, and to do it as he perceived himself. Fortunately, we had the very great advantage of audio recordings and video to help us capture his speech patterns and mannerisms. These resources were constant references for me from start to finish.

One of the biggest tools as a filmmaker, besides the material, is the visual element. We had thousands of reference photos as we designed a section of Jonestown. My production designer, Jacqueline Kay, did an amazing job adding detail and capturing the details of the town. We had to make some design changes due to budget restrictions, but I’m very satisfied with what we ended up with.

In terms of cinematography, I quickly decided to go for a very realistic approach. I wanted to have a rawness to it, embracing an almost documentary style-utilizing the 35mm format and handheld camera. My cinematographer, Andrew Shankweiler and I wanted the imperfection and camera movement to support the underlying tension and suspense that is present in the story. We mixed that with moments of heightened reality, using slow motion and static camera to emphasize pivotal plot points. Another asset we used to our advantage was the existence of the original news footage shot by the NBC News crew during Jonestown’s final weekend. We found ourselves incorporating its shot selection and coverage to inform in creating another layer of realism and authenticity.

Through the process of this project I’ve encountered so many people whose knowledge of this event is completely skewed. The consensus – the limited and crude understanding of the circumstances and events leading up to November 18th, 1978 – seems to be that Peoples Temple was a cult made up of crazy people, who drank poison. My big goal for this film was to give a deeper understanding on how this might have happened. I cannot give an ultimate answer – and in fact no one can – but I intend to raise questions and awareness.

For me, it was important to never use the word “cult,” nor to pass judgment on either the people or Jim Jones. Cinema has the ability to inform and educate, with the power to contribute change – something that goes beyond the purpose of entertainment – and I do not take that responsibility lightly. That became the foundation for this project. The initial response has been curiosity, which has sparked spirited dialogue, and many people have gone on to do further research. That alone gives me great satisfaction and is an achievement in itself.

Another thing that was both very strange and fascinating throughout this project was my discovery of the number of people with a personal connection to the story. I learned early on that Stephen Lighthill, the head of the cinematography department at AFI, was originally approached to be the cameraman on the NBC crew that went to Jonestown, but he turned it down, due to a prior commitment to a feature film project he was doing. Instead, the job went to his close friend Bob Brown, who was one of the five people shot to death at the Port Kaituma airstrip. Lighthill was able to give us information about how the camera equipment was used and style of shooting, which became an important element in the film.

In addition, during principal photography, two of our extras told of their direct links to Peoples Temple and Jonestown. One woman had lived in Jonestown for two years, while another got an invitation to move down, but declined. I did not learn about this until after we shot the movie, as they didn’t want people on set to know this. It must have been hard to go through it again as we were dramatizing events they were so close to. Surely they lost friends and acquaintances in Guyana. But I admire their courage and support for being there.

Finally, one of my directing teachers at AFI knew Tim Reiterman and told me about how the reporter coped after Jonestown. Some of these insights went into the character arc of our protagonist.

As I was doing this project, I realized that my curiosity and attention was drawn more and more towards the character of Jim Jones. The amount of information in his biography, in tape recordings, and in Temple documents, gave such a rich foundation to his character and different nuances that I wanted to explore further. I had to restrain myself and focus on what the story really was about. It did however spark my passion to continue the exploration in a feature film adaptation, which will focus on the start of Peoples Temple and Jim Jones, its years of growth, vibrancy and success, and its slow, downhill spiral. It is a huge endeavor, which will demand even more research, insight and structure. Hopefully, with help and firsthand accounts from people who were there, I can tell that story as well.

The main reason to take this story further is the necessity to delve even deeper into the psychology of the subject, which a short film can never really do, and give a wider audience the ability to learn and understand what went on behind the scenes. I must admit that the short I’ve made surely doesn’t give the weight and complexity the Peoples Temple story deserves. It is more of a stepping stone towards something profound and great.

I encourage the readers to contact me with questions, critiques or just to chat more about the process. Please do not hesitate!

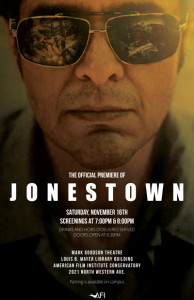

(The trailer for the film Jonestown is here. A blogpost about the film is here. David B. Berget is a directing fellow at the American Film Institute. Rated the best film school in the world, its teachers include working professionals and mentors. He can be reached at send@davidberget.com.)