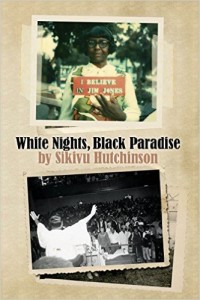

In answer to Jim Jones’ resonating question, Sikivu Hutchinson has written a novel that defiantly shouts Yes! White Nights, Black Paradise frames Peoples Temple and Jonestown within an African-American perspective, something which no published novel has yet managed. Of the handful of literary novels on the subject, the two works closest to it – Jonestown (1996) by Wilson Harris and Children of Paradise by Fred d’Aguiar (2015) – were written by Guyanese men. “Coming from the vantage point of a Black woman writer, in a field – Jonestown scholarship and fiction – where African American feminist analyses are few, I have sought to creatively illuminate (and problematize) what is still a turbulent and evolving historical record and signal event in the ‘psychic space’ of African American migrations,” writes Hutchinson in her author’s note to the 354-page fiction.

In answer to Jim Jones’ resonating question, Sikivu Hutchinson has written a novel that defiantly shouts Yes! White Nights, Black Paradise frames Peoples Temple and Jonestown within an African-American perspective, something which no published novel has yet managed. Of the handful of literary novels on the subject, the two works closest to it – Jonestown (1996) by Wilson Harris and Children of Paradise by Fred d’Aguiar (2015) – were written by Guyanese men. “Coming from the vantage point of a Black woman writer, in a field – Jonestown scholarship and fiction – where African American feminist analyses are few, I have sought to creatively illuminate (and problematize) what is still a turbulent and evolving historical record and signal event in the ‘psychic space’ of African American migrations,” writes Hutchinson in her author’s note to the 354-page fiction.

Multiple characters – some fictional, some historical – people this lyrical narrative, with a core of four African-American women at its center: the sisters Hy and Taryn Strayer, the journalist Ida Lassiter and therapist Jess McPherson, who is a member of the Planning Commission back in the States and the sole black woman with power in the Jonestown hierarchy. We inhabit the hearts and minds of many more characters, including Jimmy Jones, Jr. and his white brother, called Demian in the story, Jones Sr.’s only biological child with his wife. Hutchinson’s schema for fictionalizing some Peoples Temple members and not others results in Jim Jones as himself, but his wife, Marceline, is called Mablean. Other characters appear as composites while some are pure inventions. On her website, Hutchinson explains, “The characters in my novel (the majority of whom are fictitious) are a cross-section—they’re queer, lesbian, bisexual, trans, straight, African American, Latino, multiracial, white, age/class diverse and all over the map in terms of spiritual belief.”

While the novel moves back and forth in time, readers know where the story is destined to end, and even though many readers will have knowledge of the events of November 18, 1978, Hutchinson manages to inscribe the destination in fresh, potent and painful language.

More came to the microphone to testify, phantoms lusting for sleep. The stench of almonds nearly knocking Taryn off her feet as Jess moved ahead with the procession of speakers.

Mabelean floated past, handing out flowered Dixie cups, a fairy godmother sprinkling pixie dust.

The “pixie dust” dispersed by Jim Jones’s wife is, of course, the death potion, and this otherworldly metaphor describing what was the prelude to a brutal mass murder/suicide offers an example of Hutchinson’s sensibility in various moments throughout the novel, which, although lengthy, rushes by in a headlong dash toward inevitability.

Hutchinson’s title, White Nights, Black Paradise, has many valences. The ritual of the White Nights – rehearsals for mass suicide – is presented as theater: the residents of Jonestown participate in its urgency and action, though its ultimate meaning is still veiled in the guise of drama. It is a kind of acting.

“Play me like Dirty Harry, the gun said to Jamiah,” is the first sentence of the “White Night” chapter, about 50 pages before the novel’s end. “He’d always wanted to shoot one, just to hear the sound. The only ones he’d seen up close and personal were in cops’ holsters; lean, gleaming, black and mean.“

Jamiah is one of the novel’s African-American male characters who is drawn in by Jones’s allure – a fate the African-American women do not avoid but remain skeptical of and sometimes resistant to. Jamiah’s blackness is reflected in the gun and the power it embodies. Yet that power is always fatal: “Nigger killers, his boys in East Oakland called them. Pig talismans taking out whole families with one clip, maiming the able-bodied, silencing the innocent, swallowing a clutch of his running buddies well before sweet sixteen.” Hutchinson offers the possibility that the murder of the congressman by the Red Brigade – the Jonestown security guard comprised primarily of African-American men – is one kind of revenge for those Stateside deaths at the hands of police, as relevant in 2015 as in 1978.

But if Jonestown is indeed a “black paradise,” is its existence predicated on the White Nights, which presage the downfall of their retreat from the California ghettos gratefully abandoned by so many African-American Temple members?

As the novel’s resident skeptic, Taryn concludes:

We’re the only ones dumb enough to leave the States en masse without a plan for a way back. In fact the government is probably saying to Jim, why can’t you take some more Negroes with you? While you’re at it, take all the ghettoes of Watts, Newark, Detroit and Harlem and dump them in Jonestown. What the fuck do we care about a bunch of spooks.

Taryn’s cynicism is justified by her experiences before joining Peoples Temple, which she does skeptically, submitting to her younger sister’s will. Hy – short for Hyacinth (not to be mistaken for the elderly survivor Hyacinth Thrash, author of The Onliest One Alive) – testifies to the soft underbelly of Taryn’s tough exterior. Sexy and vibrant, Hy is a free spirit whom we meet in the opening pages as she is recovering from an abortion, driven through the night by big sister Taryn. While Taryn also drives the narrative of White Nights, Black Paradise, it is Hy’s passion that will outlive the sisters’ encounter with Peoples Temple.

Hutchinson is the author of two books of non-fiction, also published by Infidel Books: Godless Americana: Race and Religious Rebels and Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics and the Values Wars, as well as Imagining Trust, published by Peter Lang International (2003). Her skills as a researcher and interpreter of texts have primed her to become the first African-American novelist to take on the story of Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Her forthcoming talk, “No More White Saviors: Peoples Temple & Jonestown in the Black Feminist Imagination” on November 24 at the University of Southern California Center for Feminist Research promises to unite the creative and the scholarly in Hutchinson’s vision of what was found and lost in Jonestown.

(Annie Dawid, author of three volumes of fiction, lives in Colorado. Her complete collection of articles for this site may be found here. She can be reached at annie@anniedawid.com.)