(Laura Johnston Kohl conducted this interview with former Temple member Don Beck on July 23, 2013.)

Side 1

I went to college. Religion was an issue for me. When I went to college to begin with, I was a member of Campus Crusade for Christ, which was like a glorified car sales, and I couldn’t figure out which brand was the right brand, you know, and all that sort of thing. And how could only one of them be right, when there are so many out there to choose from? And I finally decided it was like spokes of a wheel, they were all right, and they all went together. And that was it, and at that point I had no more questions about religion. I had thought at one point I might become a preacher, I think it had more to do with my own struggle and finding my own identity as being a gay man. Trying to be the best little boy in the world. Anyway, then I went in the Peace Corps, after college, and that was an eye-opener for me, because I’ve never really seen a lot of the world, I’d lived a kind of sheltered life. I didn’t know much beyond my own experience. I was an only child so I was and still am, spoiled. I didn’t have any brothers or sisters, and so I always had food, clothing, shelter, that sort of thing. I never really wanted for anything. At that point I was still looking for a vocation, didn’t know what I wanted to be, which was a luxury, but I wasn’t looking for a church or religious group at all. I was still trying to figure out what it meant to be gay and where I was going to go with that and all that sort of thing.

Peace Corps was the first thing I really did on my own. It was something I chose to do and I did. In being in the Peace Corps I learned more about the US, and the fact that abroad we sort of manipulate the rest of the world, you know, we give money. I was in Bolivia, and we gave them money, but before we gave it to them, it was already, they were told how they had to spend it, you know, in buying stuff from us and all that sort of thing. So as much as I was critical of the US, I still loved and respected it. And a lot of people didn’t understand that, that you could, really when you like something, you can be more critical of it, and still like it at the same time. And I did like the States. I would say I was an idealist. I think I still am. I believe that basically that we should leave the world a better place than when we came into it, which was what I sort of was looking for but couldn’t figure out how to do it.

My first encounter with Peoples Temple was when I said, wanted to say goodbye before going into the Peace Corps to a friend of mine that was in Peace Corps, somebody I later married. And I, that was in March of 67. And I went up to, at that time the Temple was in the Redwood Valley area, meeting at a place called the Church of the Golden Rule. And so I went to a Sunday service there to see her, and I was really impressed with the children. And they had a pot luck, that was their communion. I thought that was, how fantastic, something useful. And there was a pool there, so they went swimming, that was their baptistry, and all that sort of thing. It was sort of like all of a sudden, religion or church made sort of sense. But I wasn’t interested in church at that time. It was informal, and just living and meeting and being.

Before I left they had a small meeting of the congregation. At that point it would have been probably about 30 people. And they were sitting on chairs and everybody was holding hands and they were sending love to somebody. I thought that was kinda cool, but I didn’t think much of it. They were doing something called, people were being called out, I didn’t really understand what that was. But it seemed OK, but as I say, I really wasn’t interested in that.

So I said goodbye and went on into the Peace Corps. And here’s where one of, uh. A lot of people always question, what were healings in Peoples Temple, were they real, and what were they all about? And I’m not sure, I know that a lot of the healings were faked, but I always thought of Jim Jones, from my own experience, as somebody a lot like Edgar Cayce, in that he seemed to have insights. Anyway, while I was in training, I was sitting, one day I was sitting on a log next to a stream, wondering if I was going to get through Peace Corps training, because it was something I really wanted. The next day I got a letter from this friend of mine in the Temple, and it said, you were called out yesterday and Jim said that you were sitting on a log next to a stream worried about something. And he says, “don’t worry about it. It’ll be fine. It won’t be a problem.” Now I hadn’t told anybody that. It was just thoughts, it wasn’t like somebody was watching me, or had collected information about me. It was something that I still to this day can’t explain. Blew my mind, but I sort of filed it away and went on with it.

Then there was another experience when I was in Peace Corps when I came back and had joined the church, finally. My friend told me that I was called out another time and told that she had a friend who was in Santiago, in Chile. And she said, “no, I don’t know anybody in Santiago. I know somebody in Bolivia.” And he says, “Well, no, this is some…he’s in Chile, in Santiago. And he’s sick. And he needs our love, and our help.” So they all held hands, and sent me love and whatever, and I remember at the time, it was the Christmas before, the year before I joined the Temple. One moment I was sick, and the next moment I was well. I remember that very distinctly, because it seemed to me like a fever breaking. That’s all I thought of it at the time.

[Laura: and you were in Santiago?]

And I was in Santiago, in Chile, I was not in Bolivia at the time. So, again. There wasn’t somebody, somebody couldn’t have come running down, and looked at me in Santiago, and gotten the information. It was just something that I can’t explain. Neither one of those things. And to me those were the two experiences that I had. Again I thought of Jim as somebody more like Edgar Cayce. He could, he just knew things or could pick things anyway. So I knew that, um I knew that the healings were, were faked – or at least most of them, I didn’t know that they all were, I don’t know whether they all really were – but it was supposedly to preserve Jim’s energy, if, if they did some fake ones or what not. But I still to this day don’t know that if you’re in a group of people that is consciously sending love to somebody, or holding hands and focusing their energy to help somebody, I think something could come out of that. It could be akin to a miracle, or or help, I can’t – or healing – I don’t know. Anyway, that’s where I am, what I have about that. So I believed again, he was like, somebody like Edgar Cayce. [takes deep breath]

We ha..I think we had some inklings that Jim was um… something more than just a, a person. That somehow he was chosen or whatever. Really this is, I mean there was a part of me that believed that maybe there was something more going on than just, not necessarily that he was God, or he was Jesus, or reincarnations, I didn’t know that, but it just seemed like, as I say, cause he knew things that I couldn’t explain.

The thing is with, one of the things about that, is if you give a somebody a special status, it sort of, um, it’s a way of giving up your own power, your own control. And you’re avoiding responsibility for planning for yourself, you’re letting somebody else take control, in little ways that could build something bigger. And uh, this relates to something that was in Leigh Fondakowski’s new book, Stories from Jonestown, where somebody talked about the story about Peoples Temple, the survivors, it’s never possible to finish the story. It’s the human condition. We asked Jim Jones to be something, he, we played into it, we asked him for something a person cannot be. And we can say we were disillusioned, but what’s more useful is to recognize that human capacity to not take responsibility for your own thoughts and actions. It serves a need for us. Anyone who signed on had something to gain. It was a relief from your own personal confusion. Jim gave simple answers, and we put demands on him, that’s what came out of it, and I think that’s a good statement of what it was all about.

Anyway, going on – after Peace Corps, I ended up in graduate school at Berkeley in September of ‘69. And I found graduate school rather disappointing after being in Peace Corps, which was: What are the three most important things in peoples’ lives? Food, clothing and shelter. And in grad school I said, “No, no, no, no, no. It’s, how do people feel when they walk across open spaces?” and stuff like that, so I thought, “this is just bullshit.” So anyway, I ended up reconnecting with my friend, who came by and saw me in Berkeley in December of ‘69. And at that point I told her I was gay, and she says, “Oh. I figured as much. So what?” So then I asked how the Temple was, because I knew she was in the Temple, and I asked about coming to meetings. [Phone rings] Pause here. Hello, Mac. Hello? How are you doing? I’m doing an interview with Laura. O.K. O.K. We’re nailing down a date for our dinner. [end of side 1]

Side 2

[Laura: This is Don Beck, continuing on his oral history presentation, our interview July 23, 2013.]

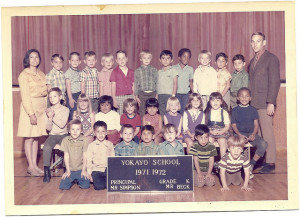

Ready? So, my partner came to see me in, or my friend came to see me in Berkeley, and I told her I was gay, and she says, [garbled] knew, and I was disappointed with graduate school, and in fact a friend of mine that I had been going with had given me some casserole with pot in it and I went on this like, a trip, sort of like Alice down the rabbit hole, and I remember thinking of all sorts of stuff, and Jim Jones’ name popped up. And then all of a sudden the next day, or two days later, Bonnie, this friend of mine, showed up at my door. And so I ended up asking her how church was, and could I come to a meeting? And I guess I was cleared because I ended up going to meetings. And at the first meeting I stood up and said I was gay, and nobody really cared. [Sound of phone ringing.] And we went from there. [Sound of phone ringing.] Um, I was uh, I moved to Redwood Valley of course, and dropped out of school. I was really impressed with a group that seemed to be doing a lot of good works. It was very down to earth, no pretense, hands and feet on prayers, just sort of practical, the steps in living that were necessary, making sure people lived well. We ended up getting married, so we could take in children. And after three months, we already had a house and three children. Many in Peoples Temple at that point took in children under what’s known as guardianship, to get them out of like a big city, urban setting, into a rural setting that seemed to be safer and all that sort of thing, so we were doing a lot of guardianships. And we ended up with three kids on guardianship. Ended up getting a job with the Ukiah School District, and I got a teaching credential through my Peace Corps service, and I eventually taught for ten years in a bilingual program there in Ukiah that I helped set up. Anyway, in Peoples Temple, I worked with the children’s program. We had something like, for example, instead of Sunday School we had Wednesday school, which was in the evening, kids came in for tutoring at the church, or sometimes it was Monday school, because it was on a Monday evening, whenever we scheduled it for kids that needed help in tutoring. And then also the various, several people that worked with swimming opened the pool up, because the church had, was half pool, and half tables and chairs and that sort of thing. So another part of the children’s program was learning to swim. Now, um, they also, the kids also had classes taught by seniors. For example you could see on a Saturday afternoon, somebody, a woman 90 years old, was teaching some preschool kids on how to make a salad. Or how to make a sandwich, or whatever. It was really beautiful. Because the kids loved it as much as the seniors. I don’t know who got more out of it, maybe the seniors did. So anyway, Loretta, who was the organist, decided that since I worked with children I should be junior choir director, because they didn’t have one. Um, and I, I sort of balked, I said, you know I don’t, I can’t even sing, I’m not that good. And she said, “ah, you’ll be fine.” Because I worked well with kids, I seemed to be working well with kids, and so actually I was more like a conductor. I mean, she got the songs, and we practiced and they followed my cue, and it was actually kind of fun. So there I was, the junior choir director, all of a sudden.

In the summers, we had special programs for the children, they’d go on a one or two-week trip. For example, I remember one year they went up to a farm up in Oregon which a member owned and the kids would spend a week there, and then they, on that particular year they came back and went down to San Felipe in Baja, California and spent a week on the beach, and it was basically Jim and a few adults, and all the kids. And it was wonderful.

In the summers, we had special programs for the children, they’d go on a one or two-week trip. For example, I remember one year they went up to a farm up in Oregon which a member owned and the kids would spend a week there, and then they, on that particular year they came back and went down to San Felipe in Baja, California and spent a week on the beach, and it was basically Jim and a few adults, and all the kids. And it was wonderful.

I quickly became involved in other activities in the Temple, for example, being on counsel. Working in groups counseling in Redwood Valley, driving to Santa Rosa counselor sessions where we had a college house there, that because we sponsored students in college. And there was also counseling in San Francisco and in LA on trips, working with people, problem-solving. Again, it was the sort of thing that impressed me, because people cared enough about each other to sit down and and and solve problems. It was the sort of thing where if somebody wanted to have a bake sale, you could organize a bake sale on a moment’s notice. Or if somebody needed to move, you’d get 4 or 5 people there to move them out and clean their house and, and so in 2 hours they’re already moved, and house cleaned, they’re ready to go kind of thing, and it just worked. People did it. I was particularly impressed with the fact that, it’s something I had believed in, that the wisdom of ordinary folks, with common sense experience and common goals, with hopes and trust in one another, in working together, that common sense basically was much more important than college learning, because it seemed like here was a group of people that seemed to know more just in being together and working together than I had encountered elsewhere.

Eventually the pattern was that we would travel every weekend, since I always lived in Ukiah, either to San Francisco for services over the weekend, or San Francisco on a Friday, and then go on to LA over the weekend. So we were always traveling, traveling, traveling, which got to be boring after a time, but the kids loved it. It seemed like we had meetings, meetings, meetings. I really did get tired of meetings, but we just did it. It was a part of, a way of gathering people, bringing them into the community, of building a community. You never knew quite what was going to happen in each service because each service was like a different show. Depending on who was there, Jim would sort of conduct, could be something that was aimed at fundamentalists, or could be something that was aimed at atheists, or it could be something that was aimed at socialists, it sort of depended on who was in the audience. Who were the new people visiting him? Sometimes when we had a mix of fundamentalists and socialists, it was an interesting thing that he could actually speak and bring it together where both would be satisfied and both would be impressed.

We also had a what we called outreach, that was on basically summer bus trips, where we’d go across the country from California back to the East Coast and back, it might be through Houston, and Washington, DC, and New York, and Chicago and Detroit and Philadelphia, and then sometimes we went up to Seattle and even Vancouver. And ahead of the bus of – well we eventually had 11 buses. When I first got there, all we had was one bus, the green bus. That, that, that.. didn’t really go very well, but we used it quite a bit, the green bus. It sort of died. And then we bought, started buying buses, old Greyhound buses, we ended up with 13 buses, so you have 13 buses of congregation going to meetings. And ahead of the buses that brought people in for meetings, we’d have what was known as pamphleting. So you’d get a group of people that would go ahead to cities to pamphlet and let the people in the city know that Peoples Temple was coming and that they should attend. I ended up working on greeting people. We called that working “on the door.” Greeting new people. And we would usually turn away people that were either heavily religious or didn’t seem like they would be interested in our services. It was a way of screening. We’d find out about people, and fill in cards of information that went to people, Carolyn and other people. I basically hated working on the door. Some people liked it but I absolutely hated it. But, I did it. I loved working with junior choir. Junior choir always started off each service, usually several numbers, always with something called “Welcome,” that sort of welcomed everybody in. And the kids loved it, punched out the song. And Loretta would find other songs that we’d work up, and they’d do that, sometimes they’d do several numbers, sometimes just one. The kids were always wonderful.

I ended up on something called Planning Commission, I’m not sure when that was created. It seems like, as I said I was in from 1970 until 1978, when everything came down. And there’s a whole section of time in there that just sort of, I can’t remember much of. It just seemed like a lot happened, but I couldn’t tell you when exactly what happened. [pause] And, and one thing is, Planning Commission seems to have been created I think somewhere in maybe 72, 73, I’m not sure when. And at first everybody, well, it was supposed to be an honor to be on it, because you were one of the, one of the elders, the church elders, and that meant you were on counseling, and all this sort of thing. And then other people wanted to be on it, so some people were put on it because they wanted to be on it, cause they were … one spouse was on, but the other wasn’t, so then they both were on, and then once you were on it, you decided, Oh, I should have stayed off it because it’s too many meetings. Too, too long. They usually started at 9pm and went until 1am, but sometimes, but not always, they went later. There were some people who asserted that they always went all night long, but they didn’t always go all night long. Often, but not always.

Though we made decisions in Planning Commission, the final authority was always with Jim Jones, and it seemed like, um, that we were there to just sort of rubber-stamp it, but not necessarily. We were discussing as well. That was sort of – you knew he was always going to have final say, but at least he was supposedly trying to involve us in what was being decided, and we did do a lot of stuff there.

The thing that I was impressed with, and drew me to the Temple was that it was a place where a community of people were putting their beliefs into practice. It was like, putting hands and feet on prayers, as we called it. We did letter-writing campaigns to support things that we liked as I said. We might have been critical of the United States, but we wanted to work within the system and make it a better place. We did drug detox, bringing people off of drugs. We took in animals. We gave food and clothing to people that needed them. It seemed like a lot of the churches and groups in Ukiah area sent us their needy people and we always helped them. We gave legal support to a lot of people that needed it. We did care of seniors, actually set up 2 senior centers, senior centers homes. We supported events like marching in Fresno in support of free press and various other things. And in Redwood Valley, they set up communes. You know, following our beliefs, socialist beliefs in cooperation and cooperativeness by setting up communes, first in Redwood Valley and then eventually in San Francisco when we got there. As we moved to San Francisco and embraced a larger community, we wondered if we could build here and what we wanted. What community we could build, and if not here, like for example, although Ukiah seemed like a good place to begin with, the City was better later on because it seemed like we could have access to more people and could do more things there. But maybe there was, who knows where? Maybe we could find. So we started looking for other places to maybe build. And, in December of ’73 I was in with a group of about 10 people who went to Guyana, and we were looking at land there for a leasehold; we said it was about I think 20,000 acres was what we were quoting, but they wanted us, we had to step into it gradually, so the first section was about 5,000 acres to begin with. We were to be a model program tying into Guyana’s desire to populate more of the country and not just Georgetown. So that’s how we appealed to them, and then we sort of served each other’s, scratched each other’s back sort of thing. I went back in the summer of ’74, as the road was being built and land cleared. We had bought a boat that brought down 12 people, it was coming down in August. And when I got there in June, Mom and Pop Jackson were already there, they were like, in their 80s and 90s. Pop Jackson was a corker, he was just…he loved the place, he loved working in the “Promised Land” he called it. He’d plant things and he’d build furniture, and he helped build in construction and he was just…you’d watch him work and you’d get tired just watching him work, because the man was just a dynamo. And his wife was too, but she was not as active as he was. He was really a delight. The boat came down and I ended up returning to Ukiah and teaching at the end of the summer.

At that point, people weren’t living in Jonestown, they were in a place called Matthews Ridge until the first buildings were erected. Now the first buildings and people living in Jonestown was about, would have been in January of 1975. There was a plane trip down for the Planning Commission in December of ’74 and that’s when Mr. Muggs came down, the chimpanzee. And they had built the cage for him and they brought him, we brought him down on the plane. And he ended up staying in Guyana, so he was the actual first permanent resident in Jonestown. At that point Joyce Touchette, who was the person that was sort of his mother, took care of him, was already there, and so there was this big cage for him, and he seemed to like it. Loved it very much. Back in the States while I was still working teaching, [somehow?] I worked with several other people procuring educational things and other things needed in Jonestown for the agricultural project.

I returned in June of ’76, that would have been two summers later, for the summer. At that point there was probably anywhere from 30 to 40 people there. At first from San Francisco I had left with a pamphleting crew, because there was a bus trip going across the country, and when we got to New York City, Tom Grubbs and I both left for Guyana, and flew to Guyana for the summer to help set up classes for the students. There were about 10 students there, student age, that needed some classes, so we were there to set that up.

Most of the children there were children that hadn’t done really well in an urban setting, they weren’t doing well back home in San Francisco or Ukiah or what not, so the project in Jonestown was a place where they could go and sort of live in a different way and just sort of work in ways that were practical, and most of the ones that went down, practically all of them, seemed to really thrive in the work atmosphere there. I mean there was a – at that point, as I say, there were only about 30, 40 people, and there was a lot of things to do. The tropical area, I found, was beautiful. One example was, one person who was having trouble with schools in the States ended up going down, he was put in charge of raising the bananas. And here was a kid that was like in high school, he was in charge of growing bananas. And we grew enough bananas that we were selling them to the army that was down there until, whatever. Then there was another fellow, Anthony Simon, who I worked with, from Los Angeles. He had gone down because he was having problems – I’m not sure what exactly – but he became interested in growing chickens, so he worked in the chickenry and we had some college texts about animal husbandry, and he would read them, even though he was a poor reader, he learned how to read by reading college texts. And in fact, when you asked him questions, he would tell you what page and what book whatever information he was quoting was from. He just became almost obsessed with doing it, and very focused and total change from what he had been in the States. Other people went down, ended up heading planting crews and we were growing at that point sweet potatoes, cassava, eddoes, bananas, pineapples, they were planting orange trees and coffee trees, I believe, at the time, too. And we had a garden for just food for just uh, eating in the, you know, for planting things like eggplant, grew really well there, peppers, carrots, whatever. That summer I did a survey and map of the parts of the project that had been developed and built. I worked with Chris Lewis, Chris Lewis on that. Chris Lewis was, had been in our detox program, and I guess he had been on heroin at one point, and he was a hard worker when he wanted to be, like most of us are. I don’t think he liked working with me, but we did a lot of work together and got to know each other. That’s one thing that also impressed me about the Temple was the fact that you could bring so many different people together from different backgrounds and ages and because we all sort of had trust in Jim Jones and the ideas that he represented for us, we somehow transferred that trust into trust for each other. So as a community we ended up trusting each other and in trusting each other we could work together well. Even though we might not have been best buddies, but we did work well together. And it’s amazing what can be done when you actually work together, as opposed to just sort of working to do the minimum. I also worked with a lot of the local agricultural persons, and, to learn about farming and planting there, which I found fascinating. I mean, I loved the area anyway, but the people that we worked with that were working with us to do planting and so on, because we hired locals to work with us, knew so much about it and we learned a lot from them. The soil was very acidic there, in fact that area that we were in was actually non-agricultural, considered non-agricultural land. But if you beefed it up enough it would grow things, but maybe not as well as other places. Which was always sort of sad that it wasn’t better. The soil was very acidic and we brought in shells, there was a reef, out in the ocean there was like a big sand bar – old shells, that were all from over thousands of years, I guess, broken and at peace, whatever, and they went out and brought them, we paid somebody to go out and bring us loads of shell in, and the calcium in the shells helped lower the acidity in the soil, so that things would actually grow better. Because acidic soil is good for some plants, and nonacidic for others, most of the things you needed for farming were somewhere in the middle. So that was one way of making the soil better. I found the rainforest awesome. I thought it was both peaceful and beautiful at the same time. One of the things I learned from the locals there was that uh – when you walk through the jungle you had to walk fast enough, you had to walk fast enough, let’s see, you had to walk slow enough so that the animals or things there knew you were coming and would normally get out of your way, and you had to walk fast enough so that you didn’t stay too long, that they figured you were a problem. So it was like sort of a happy medium. And most of the animals, I guess there were snakes that were a problem, there were big spiders like tarantulas, but they weren’t so bad, and there were actually other things, too. But you never saw them really because again, if you walked correctly, they’d all flee from you.

Um, the whole area did seem like a Promised Land, just like Pop Jackson said. With only 50 people there, and Jim Jones wasn’t there at the time, and there were no meetings, meetings, meetings. There were no meetings. Only a communal, collaborative effort. We were building a place for our community, we all had this common goal in mind, so there was a very unifying effect. I was most impressed with Joyce Touchette, because she was like an earth mother to everybody and she sort of pulled it together in many ways. Charlie was a hard worker, too, but Joyce sort of, not only in taking care of him and Muggs and the people, she was just sort of gluing things together like women do in the motherhood role, more than men do. Anyway, she was an amazing person, a hard worker, and a good problem-solver. She was the kind of person that, when somebody brought her a problem, she didn’t add to the problem. She helped defuse it. At the end of the summer, Tom Grubbs and I had set up as I say a program, teaching program. I wanted to stay and Tom Grubbs wanted to go back to the States, cause he wanted, he was taking classes in special education, he wanted to learn more. Well it was decided that I was to go back and he was to stay, because, partly because he had a credential that allowed him to be an administrator. He could be like a principal of stuff. But it was always sort of weird, because I was the one that wanted to stay and I couldn’t, and he was the one that didn’t, and he had to. Which was sometimes it seemed like the Temple did things that, according to what you didn’t want to do, but anyway. I came back and once I was back in the States, I was living at the Ranch at that point, and one of the things I did was record tapes for Jonestown. We had a couple of tape recorders doing 1-inch tapes, and they had, we’d tape movies off of TV and send them down. The Ranch grapes, there were like 40 acres of grapes there as well, and at that point I think was when they were making grape juice, which was really good, especially if you left it out of the refrigerator for a couple days (laughs). And um, one of the things I remember, too, at that point I think and again, and here, too, this is where it’s all kind of fuzzy because many years seemed to lump together for me in my memory and I don’t know whether that’s just, would have been me anyway, or whether that was just because it’s so long ago and uh, I have spent many years pushing it all back.

At that point I think, was when we were trying to meet with the Black Muslims, we learned phrases in meetings and so on, and we even went to several meetings at the Muslim Temple in San Francisco, which was just down the block from us, so they were, they were neighbors. And for a white group to meet with the Muslims was, kind of a novelty, just didn’t happen. But it happened with us. And I think Jim and others ended up going all around the country to various meetings of theirs in places throughout the country. As I say, the years in Peoples Temple were kind of blurred over time. I just know that we, many things happened. We had bus trips, we formed Planning Commission, we bought the San Francisco and Los Angeles Temple. We had a fire in the San Francisco Temple, twice. People joined and people left, and, and it was all sort of in my mind as sort of a moosh-mosh. Then all of a sudden it seemed like the summer of ’77 was upon us, and, and that was sort of a watershed time, because suddenly all in, we were working and gathering things and sending them down to Guyana, all of a sudden this article came out from New West that was supposed to be negative towards Jim, and there was this sort of rise in paranoia about the establishment trying to get us, and all that sort of a growing sentiment towards Peoples Temple, and that people were trying to destroy it, and we had to get to a safe place where we could be ourselves. So all of a sudden, it was time to move people to Guyana. And Guyana wasn’t really ready to take in as many people as we were pushing in. Had quite a few places, but it wasn’t really ready to take everybody. And once they got there, nobody really knew exactly how to organize it all. That’s something that just sort of, uh, one thing I learned in Peace Corps was, you don’t always have to know everything you do before you do it, cause once you start it, you work it out as you go. And that’s kind of what we did in Peoples Temple. And it wasn’t until a year later that we really had a good administrative plan on how to organize Jonestown. In the States we still, cause everybody…by the end of 1977, there were probably about 800 people in Jonestown, and we ended up with just maybe like, what we called a skeleton crew back in the States waiting to go to Guyana. Being back in the States, and I was still in the group that was in Ukiah, it was like we were on hold. But the nice thing was, there were no meetings, no meetings any more. (Laughs) And I was in Ukiah and so, what meetings they had in San Francisco we didn’t go to. We also didn’t have security, and I hated security duty in the tower in Redwood Valley, watching Muggs or listening or whatever. Anyway, I was in Redwood Valley until it all came down. Now, “until it all came down” for me represents the date November 18, 1978. I’ve never known what to call it exactly except “when it all came down,” because I don’t like the names the media’s given it, but I’ve never found a word or phrase that adequately captures it, except “it all came down.” That’s how I see it in my mind. Anyway, my partner, my wife and I were taking over running the Ranch until it was sold, so that uh, the people who ran it before, the Janaros, were down in Guyana.

[Laura: Can you explain what the Ranch was? I think you referred to it.]

OK, the Ranch was a place owned by the, it was a residential care facility for developmentally disabled adults. And there we had 14 guys that stayed there, we were licensed for 14. And some of them went into sheltered workshops, and some of them went into just sheltered activities during the day. But at night, they stayed with us. We had brought in, my wife and I had brought in what we called educational programming at the Ranch, because it brought in more money, for one thing. The Temple always wanted more money. And it also made it more salable to have it going, because we wanted to sell the Ranch eventually, but if this was going, it would make it more salable to people wanting to buy it, and what that consisted of was for the higher-functioning adults that were there, we’d teach them how to cook their own food, and how to take care of their own place, they were responsible for taking care of one of the facilities there, as they were learning to eventually take care of themselves. That was what the educational stuff was all about. And I worked there as well as still working in Ukiah teaching school. And then, um, all of a sudden it was November 18th, and the news of the deaths in Guyana came as bewildering to us in the States as it was to general people in the States. At least for me, I was just bewildered, and frightened and scared, and not knowing what was going on, and totally lost, as just a person on the street listening to what was going on. We were as surprised as anyone. We didn’t know what was true and what was not true in what was being reported in the first few days, cause the news kept changing: first there were this many people dead, then there were that many people dead, then there were twice as many people dead, and they were all lined up, and then who were they and all that sort of thing. Well, in San Francisco some reporter, a woman reporter for one of the TV stations came around, and said well she had a list, a first list of the people who had died, and did we want to read it? And of course we did. Well she says, “I’ll let you read it if you’ll let us film you.” And we refused, you know, we didn’t want to…that was something private. So she just walked off and said “Fine.” Then she took it to the Concerned Relatives, that was the group that was against Peoples Temple. And well we thought, you know, made us dislike them even more, cause all of a sudden she was doing this. And well, found out 25 years later, the rest of the story was, that when she went to the Concerned Relatives and presented the same deal to them, they refused as well. So here we were, you know, condemning them and it really wasn’t that way. It was like, I think 25 years later we found out we were all really the same. Some people just seemed to be following their hearts sooner than others. And thank goodness now, there’s no sense of who was in, who’s in or who’s out, because we’re all just survivors at this point. Anyway.

I never believed in, well most of us I don’t think. But I know I personally never believed in the White Night. We were always sort of told that it was being done. Jim would like point supposedly to these microphones all around us, and people were listening. This paranoia of, of, people in the States trying to take the Temple down. So we were doing this idea of a White Night, and avenging angels and so on, as a way of scaring them. I never believed it was true, that it would actually happen. But I can only surmise that things went more and more wrong with Jim Jones in Jonestown, because he’d started drugs in the States and he had sickness down there, and his paranoia was weird, he’d just gone crazy. His role was not as, I don’t think he had as clear a role of what to do as he did when he was in the States. In the States he was earning money. He was always on show. He was always sort of at the forefront. Down there, there were no more services. He was kind of running things, but he was sick, and he was not making sense, and, and … and whatever. Anyway, um, so when we had this ultimate White Night, it was a surprise I think to all of us as well. After that, I found out I was listed on the Board of Directors for the US corporation. So the first thing we did was, we met with Charles Garry and we dissolved the corporation. That was within two days or whatever, I mean, the people died on Saturday, and we were dissolving the corporation by the end of that week. And I received a bill for I think 4 and a half million dollars from the US government to pay for the evacuation of all the dead people out of Guyana. And so I called Garry and told him I didn’t have that much money in my bank account. And he said, well, don’t worry, that’s a formality. Because you’re a Board of Director, it’s just letting you know how much they’re going to be charging, because there was, in terms of the aftermath, there was somebody, a court-appointed person that would look after the financial affairs of the Temple and sort of clean them all up and decide what to do, gather the money and decide what to do with it. The first thing we did was we were called to San Francisco to be interviewed by the Secret Service. And again, they knew as much about it as we did. And they didn’t know whether to believe us, we didn’t know whether to believe them, and it was just, you know, you did the best you could, but it was really weird, all of a sudden we’re being interviewed by the Secret Service. Joyce Parks had just returned, because she had been in Caracas, at a, she was a nurse practitioner, she had been there on some sort of medical stuff. And then gradually we find out, found out, who had survived. There were people that had fled into the bush, and people that were on the new boat that was underway, so there were a number of survivors there, not everybody died in Guyana. Everybody…it was all just chaos. It was like, very disorganized. As I say, the suicides were a total surprise for me, and I think, most everybody. He practiced the White Night, but it was always done to scare people.

Overall, people from the Temple dispersed. Many formed partnerships; mostly with one or one person, or some got married and some didn’t. And some went to other parts of their family in the country, and others sort of started out in small groups in San Francisco and so on, but basically everybody dispersed. I remained married until 1982. My wife had gone back to school to finish up her degree and I had continued on in Ukiah still teaching. And when she had left Ukiah we still talked daily for about 4 or 5 years afterwards. So, we all sort of found ways, different ways of coping, and we had been offered, we’d all been offered counseling services in San Francisco from a man named Chris Hatcher, and the funny thing was, we didn’t know how to accept help and they didn’t know how to give it. Because nobody really knew what to do. We didn’t know what to do. And the people trying to help us didn’t know what to do because nothing like this had ever happened before. Now the press, as far as the press and media was concerned, the whole story ended with the suicides, so that’s one area that should be more explored as to following through, how did people survive, and what do you do in a situation like this? Anyway. [deep breath]

I stayed another year in Ukiah finishing up work at Sonoma State in education, but there was a part of me that stayed because – and I have never quite understood this – my reasoning, but this is what I thought: I wanted the people in Ukiah to know that I left of my own choice. I wasn’t forced out of Ukiah. I didn’t really want to stay, at all. But I did have a job, I was fortunate in that respect, more fortunate than others in the Temple, I had a job, and continued, and so it’s like sort of, I just kind of continued, before and after sort of thing. But eventually I got out of Ukiah, and I ended up going to Sonoma, not to Sonoma, to a college in San Rafael. I went on to studies in Special Education. In part I did it for Tom Grubbs. I know in my mind I consciously did it because Tom couldn’t do it, I was going to do it for him. Now it sounds corny, but I consciously did it for him. But it also made me more salable as a teacher, so it wasn’t that I was doing it for him, I was doing it for both of us. But my doing it for me also sort of benefited, if he couldn’t do it, at least I was doing it for him. At least that’s what I thought. So I was a bilingual and special ed teacher. I went on into special education in San Diego, middle school, junior high, after ten years of teaching kindergarten in Ukiah. And I taught for a total of 32 years and am retired now.

After it all came down I reentered life outside the Temple, contacting old friends, going back to a gay lifestyle. Going to the Bay Area on weekends as I taught my last year in Ukiah. I was back in contact with my parents, who were very supportive. They never talked much about it. After it all came down, they wanted to know, they would ask me a lot of questions. My dad couldn’t seem to understand, “but didn’t you know it was wrong, didn’t you know there was something wrong?” And then, they just stopped asking questions, and it was just sort of never spoken of. My way of dealing with it was just to sort of push it all out of my mind. I didn’t really have anybody else to talk with, except as I said I talked with my ex-wife, but we didn’t talk in a counseling way with each other, we were just supporting each other. About six months later I was talking, I had gone to see a friend of mine who was like a father-friend and guru all at once. And we were in a public place, a restaurant with a some of, couple of his other friends, and he was asking me about it all, and I remember thinking, well, this isn’t the right place to talk about it, but we did anyway, and I was crying copiously as to uh, all I could say was, “I couldn’t forgive the death of the children. I couldn’t forgive the death of the children. I will never be able to forgive that. Damn you, Jim Jones, I cannot forgive the death of the children.” That’s what came up for me. And it seemed like that relieved some tension, but I went back to suppressing it all. And like, basically that was my way of handling it. I had contact with my ex and the Janaros, Claire was always a good source of information about others and the survivors that she’d heard of. But basically that was my extent of people, I was in San Diego, anyway.

Then I heard about the, Fondakowski was making overtures to interview people, to write a play about Peoples Temple. I heard this through Claire, but I didn’t want anything to do with the Temple at all. Didn’t want anything, to talk about it, not interested at all. Eventually, several years later, when the play was about to come out, I talked to Claire about it more, and I ended up going to Berkeley, and I actually saw it twice in its first run. And in meeting survivors in San Francisco before the play and at the play was good for me. It was something that helped release a lot, and open it up and sort of like, let a lot of the energy out that had been pent up. I remember specifically, we were in this auditorium, and on the second floor and Grace Jones saw me, and she ran over screaming, “Don Beck, Don Beck!” And it was the most wonderful thing that I remember, and I remember it specifically for her, because she was always so forthright and open about it. You know, like, it made me feel wonderful. It was like coming home again. And that was a lot of what meeting other survivors was like. It was like coming back home again. And it wasn’t necessarily that you wanted to start the Temple all over again, but it was like coming back and seeing family members. And maybe the people you saw you didn’t necessarily want to spend the rest of your life with 99% of the time; maybe you’d only see them a couple of hours once. But it was like, when you came together, you knew you were part of a family and you had a common experience. You didn’t have to explain it to anybody. You might not have understood it, and they might not have understood it, but you sure understood it a hell of a lot more than people who didn’t know anything about it. Anyway, it was like coming home. [sighs]

And what came up were these wonderful feelings and memories of a community that we once had. The community. The sense of goodness in each of us is still alive. The belief in building a better world. That sense of community that I’ve never found, had never found before or since Peoples Temple. Also worked afterwards with California Historical Society. We’d get groups of people together that would look through their pictures and try to put names on the pictures and explain what they were, because they had a lot of, thousands of pictures, but they didn’t know who they were. And this was the first time they’d had a historical situation where the history, the people were still alive involved in the history, so they could get more information about it. And it was, again, another good experience. Looking at these pictures and remembering back to things you’d forgotten about. And I might not remember the name of this person, but I’d remember the name of that person. Then somebody else that I was talking to, that was right next to me, could remember the name of the person I didn’t and vice versa. And together we knew more than each of us separately. But it would bring us together as well as bringing up a lot of good remembrances. It was a very sort of freeing experience. Another good thing that I found was the website, “Jonestown, uh Alternative website.” It was, it’s sponsored by Mac and Rebecca. And it started out in North Dakota…no, South Dakota, at the university there that Becky was teaching at, and then when she came to San Diego, it came with her. The site is now on the San Diego server. And I ended up talking to Mac, and they were not very pushy or anything, and then a couple years later I talked to him again, and at this point I was more interested in making contact, and they got me together with several people that were in the Ukiah area, Laura Johnston, a couple of other people, and uh, again, it was a, this wonderful experience of coming home again. A feeling of, of goodness, and, and just being complete, maybe not complete, I don’t know how to describe it. That is as close as I can come.

Anyway, since that time I’ve worked on the site doing research and examining documents that have been released about Peoples Temple. And I know that I’m doing it selfishly, for myself, because I want to know more about what was going on down there. Why did it happen? What did it do? Because I sort of was…I realized later on that I had always lived in Ukiah. I had never really moved to San Francisco when the Temple moved to San Francisco, and it took on a different personality when it was living in San Francisco. And then when it went to Guyana, Jim Jones or the Temple took on a different personality kind of thing. And it was like, it was moving on, but I was sort of stuck back where I started. And I still saw the Temple as I had first seen it.

Looking back now, seems like there was so much going on in Jonestown. Over and over redefining, groups that would oversee what was going on, and goals and activities. And they had so many projects going that, that, they’d get something going like an educational program for the kids, and then the kids would be drawn into other activities, where they couldn’t attend school all the time. The seniors were supposed to be, the ones that couldn’t read, were supposed to be learning how to read more. And yet their time for classes were taken, because their, the classes were cancelled when something else came up. And it was like, it seemed like they were always defining so many more new things to do they never completed anything they set out to do. And which is sort of sad, and I have never quite understood that. Everybody was spread so thin it seemed like, that nothing was ever, never really able to get any project done, or, or worked on correctly, education of children, seniors, about history, planning, and building productive farming on non-agricultural land. We became more and more paralyzed, it seemed, in paranoia. Paranoia that in many ways was used to unite us, the fact that we had outside elements pressing in on us was one way of pulling us together in the States. But that also, to an extreme, can destroy you, and that’s, I think that’s what helped to destroy what we had down there. I know Jim Jones was paranoid, and his paranoia is what brought it all down. And it all came down because of the paranoia and the fact that we ended up with a leader that had too much absolute power. We were not watching that, we just had never gotten in touch with it.

Afterwards, um, some people were in touch with each other, others not in contact. There was no right or wrong way to solve it all, nobody knew what to do. Some people seemed to do better at reintegrating themselves into the US than others, and others were sort of lost, by the wayside. And um, still the way it is. If nothing else, one of the things that could come out of it, by telling and looking at now, the rest of the story, is, “What do you do after an extreme event like this? Or how do you prevent cults from developing and hurting the people they’re meant to help?” Anyway. After 25 years I found that it was for me personally, freeing, to finally bring it all up and kind of talk about it, and release all the energy, because I was using a lot of energy to just sort of forget it and um, now I reconnect with survivors, and maybe momentarily as I say, maybe I don’t want to connect with people and live with them 24/7, but like at least, to know that they’re OK, and in a way selfishly to find out what have they done with themselves, what things have they found helpful? We had a series of meetings, we decided to have, we were having get-togethers with on the memorial day of, of when everybody died, and that was through the efforts of some preacher that had yearly meetings in November. And it was always kind of hard to meet on that day because it was so, there’s a lot of sadness with it. So we decided to have gatherings when, that didn’t relate necessarily to the death of everybody, and so we had several years we had meetings around July 4th or Memorial Day, as a time to come together and not to celebrate the memory of people dying, but just to see how we’re doing and connect and talk. And there was a lot of times when people would connect and share things, it wasn’t, it didn’t have to be talking about the Temple, could be just various things, maybe we went to a movie, maybe we had dinner. Anyway it was just a way of coming together that was very positive. Coming together and see how folks are doing, and hopefully get more insights as to how to help you cope. I like the fact that there’s no longer people in or out of the Temple and we’re all survivors, just pretty much all of us believing, I started to say everybody, but I have to say, I don’t know that everybody believes this, but I think pretty much all of us have a common belief in the fact that the world can be better, can be made better, and that it works on what we do in the here and now, not wait for some time after death, or some heaven to come along, or some other planet to fly by. But the fact that we can build a better world and we could.

Conspiracy’s another topic. Was there a conspiracy? And who knows?? From, “were there really duplicate tractors in Jonestown, and Port Kaituma,” and “did US forces come in and actually kill the Peoples Temple people and pile them up neatly?” Ryan’s family suspected that the CIA could have warned or better prepared him for what he was to expect, he was sort of not told how dangerous it might be. And all of these various things have never gone anywhere. So, I, you know at this point, who knows? And in a sense, my own feeling is, I wonder. It seems to me there was something going on, but who knows? And you know, it’s unlikely that after all this time, anything new is going to emerge. So maybe, just like Kennedy’s magic bullet, you know, what’s going to happen. You know, that sort of remains the truth now. Maybe that’s the same thing with Peoples Temple, it happened the way it happened. But I look at the potential and what we had, and what we were developing, and I’m marveling, and I remember, I used to talk to Grace about how, if you imagine a city like New York City, and you know that people working, a lot of people working on an hourly wage, and the longer they took the more money they earned, so they were sort of like sandbagging on the job or not doing their highest energy. Can you imagine what could have been built if everybody was actually working to their fullest capacity? In the same amount of time? How much, what could they have built then? That’s to me the beauty of what Peoples Temple stood for. The possibility and what you could do to develop and make something better. The question of trust I think is something that we had, and then Jim Jones brought us together and gathered us. And initially we trusted him, and we continued trusting him too much; I understand that. But we also, because he maybe played a trick on us in bringing us together, he tricked us into trusting each other. And it’s amazing what people can do when they trust each other and they work together out of that trust. It’s amazing what can be done. And the the relatively little that we did, which was actually quite a bit, imagine…if you could do more of that. To me, that’s the beauty. Somehow trusting in one another, the common element is that we believed in the possibility of making a better life. At least I think we all did. We believed it, we saw it, we wanted to build it. Peoples Temple is the best community that represents that, that I’ve ever seen, and I long for that again. I think that’s when I get together with survivors, I sort of, that longing sort of comes up and yet being with other survivors I feel like it is still real. It reminds me that it actually is possible. Because there’s a connection, there’s something living that we had as a community. We had something living as a community. Wasn’t just words you sing on Sunday, or words that you sing in a hymn. It was something living in you all the time, that you cared for each other.

Ah, what do I learn from it all? Certainly more than the media’s fascination with the gore of its ending. According to the media, that’s what Peoples Temple was, the gore and horror of the ending, because that’s where it all Ended. And yet the suicides and Kool-aid were not the end of the story. Because for all the people that survive, we all continued on and there’s still more to the story. How do we continue on? What does the world do to take the energy that forms cults and make it form into something more useful? Rather than a cult that pulls everything apart. How do you avoid cults and groups getting lost in their own righteousness? You know, it’s like they just want to, “I’m right and you’re wrong, and screw you,” kind of thing and like…as opposed to “what do we have in common that we can build on and bring more into a wonderful understanding?” The PBS movie with the quote from Debbie Layton, I’ve always remembered that it points out that “no one joins a cult to die. No one joins a cult for bad purposes.” It’s a question, it’s, it’s up to us that we need to question all of our leaders. What seems wrong, to speak up about it; and what seems right, to praise and build on. Might mean leaving a group, or a family, or a church, or a town, or a county, or a state or a nation, if you find you no longer trust what the people believe in or are saying. Or, maybe your questioning what people think or say might change it back into something more meaningful, and put it back in the right direction, and which brings me to a quote that comes from a senator in the late 1800s, “my country right or wrong.” We hear a lot that quote and it stops right there, in terms of what we hear, “my country, right or wrong.” Period. But there’s more to it. “If it’s right, keep it right. And if it’s wrong, make it right.” And all of a sudden it makes sense. And to me, that’s what we didn’t do. We didn’t watch or question our leaders enough. And I think we all, that’s to me the big lesson out of Peoples Temple. That and the fact that to know and confirm that people trusting each other can build a better world. I think that’s possible.

Took me years to figure out that Peoples Temple was both bad and good. I could not figure out how something that seemed so good, could end so bad. And I felt there was something wrong with me, that I still felt there was good in it. But then I decided, the goodness of the Temple was, is and always will be, real. Because it is the goodness we, as members, brought to the Temple, and when we get together as survivors, we still have that goodness in us. Peoples Temple was not the goodness of one person. People want to point to Jim Jones and say Peoples Temple was Jim Jones. No. The goodness of Peoples Temple was the people that came together, and maybe Jim worked to bring us together, but he lost it himself, he lost sight of what he was doing, and I’m sad for him, angry with him actually. [deep sigh] That goodness remains true for now, then, and in the future.

Now, I’d like to sort of end with some things like positives that I remember: Children’s choir. Welcome, welcome, all of you, their wonderful song. Chris Rozynko, bouncing up and down like a pogo stick when we were singing in meetings. I tried it. Loved it, it was wonderful, I did it, too. Claire, dancing to her own beat in meetings, again awesome. Totally uncoordinated but the most wonderful feeling and energy I’ve ever seen. Skits that the kids and adults put on. Dancing groups. Cleaning up lawns in DC and other places in the country. Staying at peoples’ houses, how gracious and kind people were that didn’t know us, that took care of us. The beauty of common-sense people. Learning to pick and cook greens. Learning that to find that, when you picked greens, you don’t pick a handful, you gotta pick a potful, because it cooks down to practically nothing. And when I didn’t know that, the person I was staying with thought that was funny, and rightly so. I had to laugh as well. I’ve loved that story. Working in the kitchen. I worked in the kitchen on cleanup. I liked that because it had a beginning and an end. And the people were great to work with. Kitchen workers and folks selling things. I can’t remember the names of people. Don’t even remember what was being sold, but there was always some wonderful people selling all sorts of things. Cake sales, that we could have a bake sale organized instantly. And I think of, in the schools I taught at, organizing a cake sale, would take people at the schools I was in, would take them weeks. And yet we’d have it organized in 20 minutes. Patty Cartmell singing “going home.” Most amazing. Jack Beam doing Flip Wilson. The beauty of the tropics. Community, a family like I’ve never experienced before or since. Mutual trust in each other, supporting in so many ways. Joyce Touchette with Muggs. Seniors teaching preschoolers how to make a salad. Diane Wilkinson singing anything. Eva Pugh’s chili on Wednesday night at Redwood Valley meetings. Melvin Johnson singing, “Walk a mile in my shoes.” Jack Arnold’s band and senior choir. Pop Jackson’s smile, and his energy. The shafts of light coming through the jungle foliage in the tropical rainforest.

And negatives: Of course the biggest negative is the ending of Peoples Temple. It shouldn’t have ended that way. Discipline was disappointing. We never really handled discipline correctly. And I don’t know that we really ever found a way to do it in a large group, because you can’t do it the same in a large group as you do it in a small group, but yet, I don’t know, we didn’t resolve that one well. Meetings, meetings, meetings, meetings. That part I hated. Staying up all night, I hated that as well. Bus rides – hated. Not enough time for our own kids to be worked with. I mean, we had a lot of projects going, but we never could do them completely well, especially working with children, and making sure they learned. Never time enough to do what, to do many projects adequately. We were spread too thin.

Who are some of the people I remember the best? Alice Ingrahm, Reenie, the Janaros, Penny. (laughs) What a character. What happened when people broke the rules. We called it a catharsis, but again, that was a discipline. In a family, discipline emerges somehow. But when you have a large family of thousands of people, and you know everybody knew everything about everybody, which was good, but yet at the same time, how do you parse out…we didn’t resolve that one. What I remember the best is the children. And the hope. Peoples Temple to me was hope for the future. And some of the things I remember to this day getting in a car, well not every time, but sometimes I’ll think, well, we’re always supposed to wait two [noise] minutes.

What did I learn from Peoples Temple? I was not as aware of civil rights and how much we are all responsible for each other. I learned some of that in Peace Corps, but I learned more of it in Peoples Temple. And I guess that’s about it. I don’t know, do you have any questions? [noise] Big thing for me is this thing about, always questioning. Don’t be afraid to speak up. At most, it means you just don’t agree. I don’t know, when you get to the level of the country and you don’t agree with what the country’s doing I don’t know how you can complain. But certainly, in your local groups. I’ve since then, I, I’m not a joiner of groups. I’m not big on joining groups.

[Laura: How about like, if you look at your life today, how is what you’re doing today different because you were in the Temple?]

Oh, I’m not sure. Or, I think I’m as… I think the Temple allowed me to continue being an idealist, because I found confirmation that it is possible to build a better world. The world has just screwed up in doing it. But it is possible, and it’s that possibility, that hope, that we need to go on. I think a lot of problems we have nowadays is people have given up hope. Doesn’t seem to be a way out of where we’re at, and there has to be. I don’t know if I answered your question though. Would I do it all over again? I don’t regret being in Peoples Temple. I regret the ending. I will always regret the ending. But regret is something you can’t… If you like where you’re at today, and I’m, I like where I’m at, in the sense I feel like I’ve accomplished something in my life, and I’ve had a hard life, but I’ve gotten through it. I think Peoples Temple was worth it, because it gave me a lot of insights. I learned how to work with people in Peoples Temple. I became a counselor, found myself giving advice. I mean, I don’t know, maybe it’s easier to give advice than take it, but listening to people and problems, I thought was good. We need to do more of that with each other.