(This article is adapted from its original appearance from the 2014 Random House Audible release of Seductive Poison.)

(This article is adapted from its original appearance from the 2014 Random House Audible release of Seductive Poison.)

Weeks before my book came out in 1998, I was contacted by a documentary producer and asked to join his film crew on their journey to Jonestown. I was hesitant. What if the plane crashed? I could imagine the headlines: Curse of Jim Jones alive and well in Jonestown. He has taken his last victim.

I asked what new information could he bring to the story? He told me he had come across a woman’s dissertation on the history of Guyana and discovered that 100 years ago, a white minister had taken his flock to Guyana and killed them, promising them they would be resurrected. I was stunned. Could Jones have known about this piece of history? Had this inspired him?

I decided to join the film crew. Before leaving, I collected photos and letters from my brothers and sister to bring to my mother’s gravesite. I asked Stephen Jones where her makeshift grave was. I wanted to apologize to her.

On my arrival in the capital of Guyana, Georgetown, I was struck by how little things had changed. The drive from the airport to the Pegasus Hotel was as frightening as it had been twenty years ago when I was escaping. Perhaps I should not have come. Wild memories and fears were rushing forward: being shot in the back, captured and shipped back into the interior, drugged into silence in the medical unit, then paraded around the compound, bound in ropes–a painful example of what would happen if anyone else tried to leave.

Early the next morning, we flew by twin engine plane into the interior. Looking out the window and down onto the jungle, I noticed a long switchback line that went on forever. I asked the pilot what we were flying over. ‘The Kaituma river,” he yelled back. I was suddenly struck by how demonic it was for Jones to bring all the babies and frail seniors into the interior across the ocean, followed by nine exhausting hours up the Kaituma River. Even though I had written my memoir, I had yet to realize the true evilness of Jones’ decision to choose this outpost in the middle of nowhere, 250 miles from civilization, the impenetrable jungle our prison bars.

We landed in the bush in a small clearing in Port Kaituma. Hens scattered and squawked their disapproval; the cows stood, wholly unimpressed, as we whooshed by. We boarded a sputtering truck and drove over a much-improved dirt road, built by lumber excavators denuding the forest. When our vehicle slowed to turn off the main dirt road, we began a jarring ride over a rutted, crevassed trail, heading deeper into the jungle. Forty minutes later, the trail ended, and thick jungle encircled and threatened us. Tangled branches armed with needle sharp spikes tore and stung our skin. Blood was dripping from my cheek when we finally pulled to a stop.

All around us, the jungle had reclaimed what was once Jonestown. Here, where the Pavilion stood, where we were forced to gather nightly to be indoctrinated, confronted and punished, the land was barren. The entire expanse of the Pavilion and the clearing beyond – where 913 people, 304 innocent children among them, had been poisoned – had remained toxic. The cyanide from the bodies had seeped into the soil as they decomposed under the relentless jungle sun. Not even a blade of grass could be seen.

The fence that had encircled the Pavilion had disintegrated; the radio room with its constant wireless hum was gone. The wooden walkways, the kitchens, alive with women’s melodious voices, had vanished; the cabin where Mama had whispered her fears and shared Mary’s forbidden marmalade, had been devoured by jungle. The tin roof that kept the rain from soaking our exhausted bodies during our all-night meetings had long since been scavenged by the Amerindians. Gone was Jones’ armchair where he decreed daily how we would live and ultimately die. From high in a tree, a haunting reminder that life in the jungle did not abide by civilization’s rules, a rusted portion of the flatbed truck that used to transport us into the encampment had been ensnared and lifted into the sky—a silent witness to a tragedy.

Wiping the blood from my face, I gathered my backpack with all its memorabilia and began my walk to Mama’s grave. I would finally say good-bye. A cacophony of insect noises emanated from beneath and around me. I stood still, waiting to feel her presence. An enormous black-shelled beetle whizzed by as several macaws called out from the green canopy above.

But Mama was not here. No remembrance of voices drifted through the humid air. All was silent. Nothing remained. Those who had perished in Jonestown had fled long, long ago, returning to the places they had loved so well in life. My mother was in the breeze of the Sierra Mountains; dipping her feet in the cold volcanic lake at Mount Lassen; sitting on the edge of my daughter’s bed as we read bedtime stories. The memory of her fear, pain and death would never be a part of her essence, not here, not now, not ever.

On my return, I was approached by Stanford University professor, Dr. Philip Zimbardo – famous for his Stanford Prison Study – and asked if I would speak to a class of several hundred of his psychology students. I was petrified. My book wasn’t out yet. I had never done any public speaking. I had written my story alone, without an audience. I had yet to stand and face a group of people.

On the day of the event, I wore a sweater in case I started sweating profusely. I arrived early and sat in the back of the auditorium, watching the students enter and take their seats. They were the age I had been when Jim Jones told me how very special I was; the age we yearn to be taken seriously by an adult.

A large Power Point announced Guest Speaker ~ Jonestown Survivor- Deborah Layton. Students took their seats around me, whispering and looking for the bizarre mohawked, multiple ear-ringed cult survivor.

When Zimbardo came to the podium and asked the class to welcome me, a drop of sweat began to run down the inside of my sweater. I got up and heard a faint gasp. As I made my way down the long aisle to the front of the auditorium, astonished faces stared back. I heard a muffled “She looks normal…” “Yeah, like my aunt…”

Stepping onto the stage, I took a deep breath, afraid I might hyperventilate and pass out. As I spoke, I stared out into the sea of young vibrant faces and knew they despised me; they were thinking, how could anyone be that stupid? Midway through my talk I saw a young woman whisper into the ear of the boy next to her. I was embarrassed and ashamed – she was disinterested and devising a plan to leave early. Another student closed his eyes and fell asleep, bored by my blathering.

When I finished – convinced that I had only proven what a fool I was – the assemblage in the lecture hall rose and gave me a standing ovation. Students streamed down the aisles and lined up to speak with me. The girl who had been whispering to the boy stood before me and said, “During your talk I couldn’t help but tell my boyfriend how frightening your story is.” Several students later, the napping student reached his hand forward to shake mine. “Your depiction was so evocative I just had to close my eyes to be in Jonestown.” As I drove home that evening, I wondered if I had wasted 20 years being afraid of how others would perceive and judge me.

Ironically, after Jonestown, I once again blindly followed the same dangerous pattern on the trade floor. I never questioned or complained, silently accepted fourteen-hour days, wholly trusted the partners I worked with and believed I would be rewarded. But as my indoctrination crumbled away, I was surprised to discover that accomplished, wealthy stockbrokers were spending tons of money to attend grueling, all-weekend meetings, locked away behind closed doors where non-believers were not welcome, and that they suffered being violently criticized and yelled at without permission to defend themselves—all to attain “enlightenment” and greater business savvy.

As I watched these intelligent and successful men relinquish their power to a leader I realized that although my experience with Jim Jones had been extreme, leader terror, group think and peer pressure were alive and well even in corporate America. I felt I was witnessing the “culting of America” at my workplace – a set of ethical beliefs that mirror Peoples Temple’s: the end justifies the means; “our” way is the only way; if you are not with us you are against us.

* * * * *

I had learned many things from my first captor: that flattery lowers the recipient’s defenses; exhaustion keeps the mind from thinking clearly; and isolation from family and friends causes a disruption of our internal compass.

Troubled by what I was witnessing at work and desperately worried that I had no answers to my daughter’s questions, it all came to a crescendo one afternoon on the trade floor. Suddenly “…Just drink the fucking Kool-aid, Jack…” crackled across the room. It felt as though the air had been suctioned from my lungs. My hands began to tremble, the color drained from my face, but – like the good chameleon Jones had trained me to be – I cloaked my emotions and laughed with the others. But my resolve was strengthened. My decision was sealed: it was time for me to come out from behind the shadows, own my history and tell my story, explain to my daughter and the world how it happened to me and how it could happen to anyone anywhere.

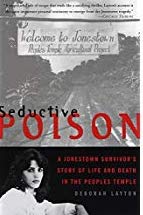

I wrote Seductive Poison to explain to the world how it is that good, smart, idealistic people got caught up in the machinations of Jim Jones, and that none of his followers were crazy, mindless automatons.

* * * * *

If we scoff at another’s experience and categorically deny it could ever happen to us, we will have learned nothing. It is only by knowing the warning signs that we can protect ourselves, our loved ones and our children: when questions are not allowed, when doubts are punished, and when contacts and friendships outside of the organization are forbidden, we are in danger. An ideal can never be brought about by fear, abuse and the threat of retribution.

In the last few years I have stopped doing documentaries—how many times can I tell my story and make it seem new, bring fresh insights? But I still speak at psychology conferences, universities and high schools where people can see me and take comfort in knowing that we can overcome our trauma. It helps to know that we are not alone, that many of us have lived through experiences we believe have made us unlovable and unacceptable, and yet, there is hope for us.

After each of my talks, people come up to thank me for telling my story and speaking honestly about my shame. My admission of failure gives them strength. Tears roll down their cheeks as they tell their own story, each soul filled with shame and the belief that they had done something to deserve abuse. If I could rise above my painful experiences, they realized, perhaps they could too.

I was taught to silence my inner voice, told my feelings and doubts were mere selfishness. Yet in the end, this all-knowing voice called out to me to run, to tell the truth, to speak out, to take a stand. To live.

* * * * *

My father lived to see the publication of my memoir. In the telling of my story, and the positive reception the book received, my father began to own this portion of the family history. I believe he, along with me, began to stand a little taller, no longer imprisoned in guilt and shame.

My brother was released in 2002, having served twenty years behind bars.

Jonestown was the largest single loss of U.S. civilian lives – including 304 children – prior to the attacks of September 11, 2001.

(Deborah Layton is a Jonestown survivor. Her previous article for the jonestown report is Chasing Serenity.)