“Kasserian Ingera,” Jim Cobb said, to begin his address at the dedication of four memorial plaques at Evergreen Cemetery in May 2011. “And how are the children?,” he asked, giving the traditional Masai warrior greeting to the assembled gathering. If we were concerned about the welfare of the children, the world would be a better place, said Jim. It would become a place where “their dreams and visions can still come true.”

James Cobb Jr., who was born in Indianapolis, Indiana on January 22, 1950, died in Oakland, California on August 25, 2024. The former member of Peoples Temple was one of the eight young adults critical of Temple practices who left the group in 1973. He became a member of the Concerned Relatives who accompanied Rep. Leo Ryan to Jonestown. After the tragedy he practiced dentistry, raised a family, and enjoyed his children, grandchildren, and life itself.

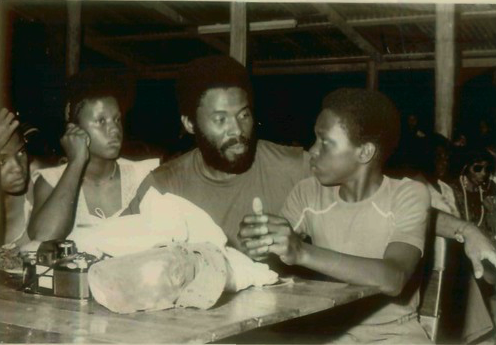

Jim was often described as a gentle giant, an imposing presence with a modesty that bordered on shyness. During reunions of Temple members, he would usually gravitate towards the people who knew him, yet he would grace anyone who approached him with a wide smile and a willingness to talk. You just had to be the one to make the approach.

His size did make him seem intimidating at times. I recall meeting him at a Starbucks near the line between Berkeley and Oakland one day to talk to him about a writing project. We sat in a corner of the eating area, with two rows of empty tables forming semicircles around us, and beyond that, crammed in the far corner of the fast food establishment, a dozen tables filled with nervous white people. He referred to the gulf between us and the rest of the customers as “the zone of blackness,” and while there was definitely that, I also think people were awed by the sheer magnitude of his physical and psychic presence.

*****

Jim Cobb’s family made the trek from Indianapolis to Ukiah in 1967, following the prophet Jim Jones. Jones had miraculously diagnosed an ear problem Cobb had the first time the seven-year-old attended Peoples Temple in Indianapolis (Raven, Reiterman and Jacobs 1982). At seventeen, Jim Cobb remained in Indianapolis to finish the baseball season – he’d dreamed of becoming a pro player. He eventually followed his family to California, however, selling off some of his coin collection to raise the money to ride the Greyhound Bus across country.

Cobb became a youth leader in the Ukiah Temple. At the Temple dorms in Santa Rosa—where students attending the community college shared living quarters—Jim “was a sort of leader by acclamation and conducted many of the meetings” (Raven). When he left Ukiah for dental school in San Francisco, however, he stopped attending Sunday services. Although he returned for a few months after a tearful reconversion in spring 1973, he left again, this time in secret, with seven other young adults that fall, including his sister Teresa. (Remembrances for Teresa Cobb, who died February 13, 2015, were written by Laura Johnston Kohl, Leslie Wagner Wilson and Vera Washington.)

Called the “Eight Revolutionaries,” they were the first major defectors from the Temple. They composed a manifesto explaining the reasons for their departure. The group carefully avoided criticizing Jim Jones, instead blaming staff for departing from socialist goals and ideals and focusing instead on sex. The letter noted the racism inherent in Temple leadership, in which new white women members advanced to positions of leadership ahead of longtime Black members.

Five years later, three of the eight revolutionaries—Jim Cobb, Wayne Pietila, and Mickey Touchette—traveled with Congressman Leo Ryan to Guyana, along with members of the Concerned Relatives group. Jim was one of four individuals allowed to go into Jonestown. He was there to see his mother Christine Cobb, his brothers Joel and John, and his sisters Brenda, Ava, and Sandy. The next day, all of them would be dead except for John, who was in Georgetown with the basketball team.

Jim was at the Port Kaituma airstrip during the shootings of Ryan and so many others in the congressional party. Even as the magnitude of the loss of his own family washed over him, Jim helped Guyanese and US authorities as much as he could to document the sequence and identify the participants in that attack. Without his eyewitness accounts, we would know much less about what happened that afternoon and who from the Jonestown community was involved.

Like so many, Jim Cobb lost family members in Jonestown. But he also saw in the Temple a remarkable attempt to change the world. “Some say we were radicals, left wing, maladjusted so and so,” he wrote, adding, “I do miss those people working and sharing that ever elusive dream, so many beautiful children. You remember their trusting smiles and jubilance? A thirsty Empire swallowed them and grows.”

Jim Cobb wanted to remind people to slow down, meditate, contemplate, and heal. One way to do this was to read, so he provided a list of more than 50 books he recommended reading. He wanted to remember “the dreams, dedication, hard work, and commitment needed to achieve the realization of a vision against forces which will always be there to try and stop us.”

My last memory of Jim was a quiet one, and one that I am happy to take into my future. It was in June 2023 in the library of the California Historical Society. Former Temple members had gathered to go through recently-processed CHS photos, making identifications and giving context to the depicted scenes. Several Temple researchers were also present, pursuing their own projects. With activity swirling around him, Jim sat alone at a table, a serious expression on his face as he did the kind of work that fewer and fewer people are able to do. But when I approached him for a hello, he rose to his feet with a transformative smile and gave me a huge bear hug. I introduced him to the researchers whom I had smuggled into the session – and who themselves were victims of the same awe in approaching Jim as the Starbucks crowd – and within minutes, they were talking like long lost friends.

I am thankful that I knew him.

(Fielding M. McGehee III is the principal researcher for the Jonestown Institute and this website, where he manages tape transcripts, Freedom of Information Act requests, primary source documents, and general inquiries on questions concerning Peoples Temple. A selection of articles and editorials for the jonestown report is here. He may be reached at fieldingmcgehee@yahoo.com.)