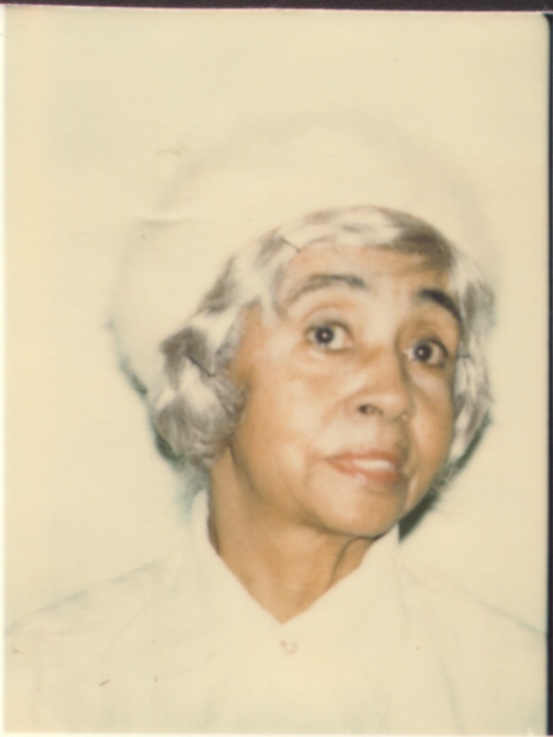

I am writing this remembrance of a woman who died in Jonestown with a bit of a handicap: I never met Hazel Hopkins Dashiell, and until earlier this summer, the only thing that I knew about was that she was my father-in-law’s cousin. I had always been curious about her, though. I wanted to learn more about her life, but I didn’t want to upset anyone in the process.

I am writing this remembrance of a woman who died in Jonestown with a bit of a handicap: I never met Hazel Hopkins Dashiell, and until earlier this summer, the only thing that I knew about was that she was my father-in-law’s cousin. I had always been curious about her, though. I wanted to learn more about her life, but I didn’t want to upset anyone in the process.

I ran into some initial resistance – no one else was willing to write Hazel’s story – but when I took it on myself, the funny thing was that everyone started talking about her, telling stories, relating memories. This is what I learned.

Hazel was a member of the Narragansett Indian Tribe of Rhode Island. The oldest of eight children, she was born on the Narragansett Indian Reservation in December of 1899. This was about 15 years after the state of Rhode Island decided that the tribe were no longer “Indians” – and hence no longer entitled to reservation land – and all the land was sold, except for a few acres that the old Indian Church sits on. Apparently, however, the tribe decided not to abide by that decision. They continued to live as a tribe and practice their ancient culture, and eventually they gained Federal recognition. At the turn of the century – around the time that Hazel was born – most of the tribe still lived there in houses they had built themselves. Quite a few had no electricity or running water.

Nearly all of the tribal men worked as laborers in various fields. Many were – and still are – well known as skilled masons, and their stonework has stood for centuries all over New England. A number of the women worked as housekeepers or nannies for the white families of New England. It wasn’t – and still isn’t – uncommon for tribal members to supplement their income by living off the land.

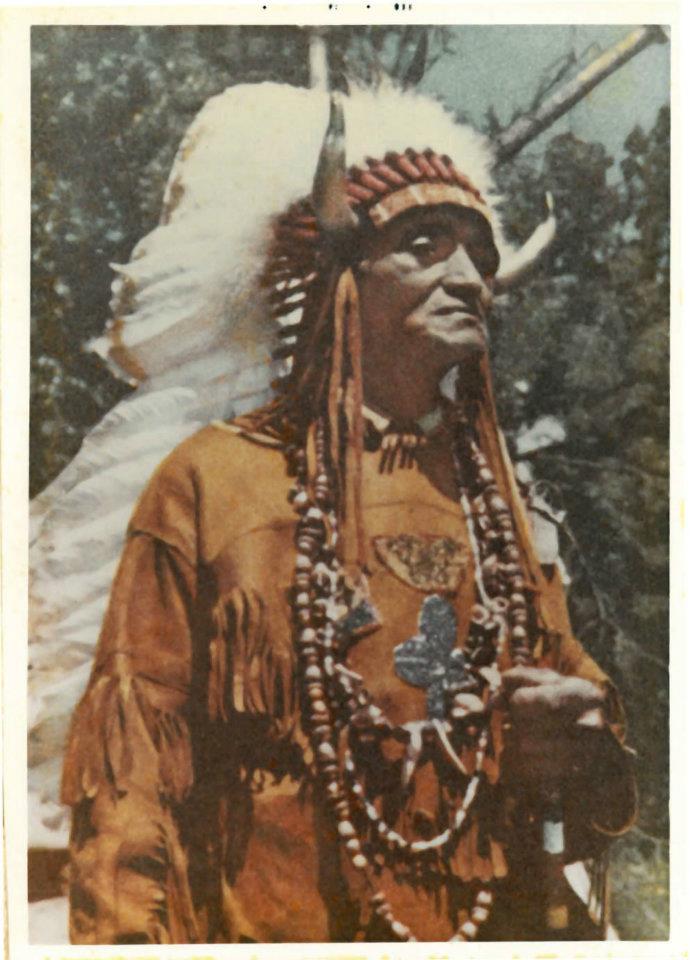

Hazel comes from a very proud family. Her uncle was medicine man Pine Tree who was instrumental in the tribe’s fight to win back some of their traditional lands and rights. Her brother George Hopkins “Broken Arrow” was a well-loved and respected Chief Sachem of the tribe. Most tribal members, including Hazel, can document their genealogy through royal bloodlines back to precolonial times. She had a lot to be proud of, but sadly, the Narragansett people still face racism and persecution from outsiders who don’t understand their way of living.

The effect of this long history, combined with pressure from outsiders, causes the tribe to band even closer, to always take care of their own, to be suspicious of anyone they don’t know, and to be protective to the point of secrecy about practicing their culture. When I consider all of this, it becomes clear to me how she could have gotten lured into promises of a communal paradise free from racism and outsiders, which was how life in Jonestown was presented to members of Peoples Temple.

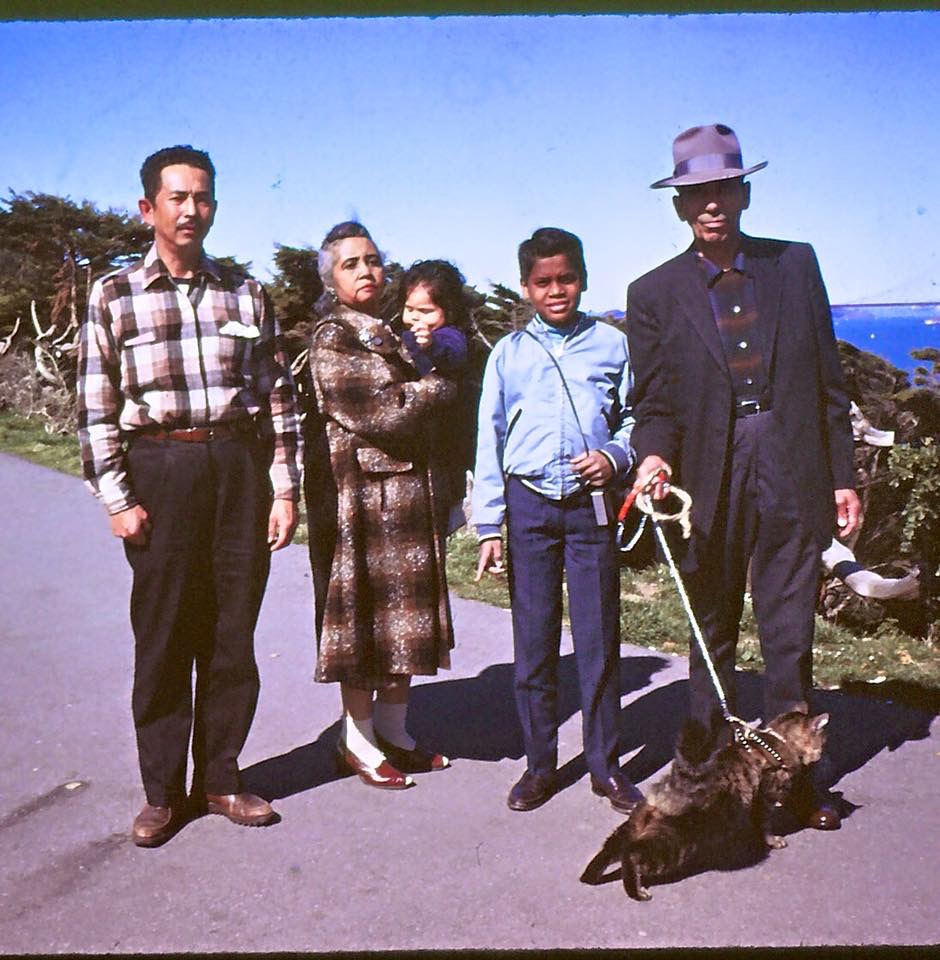

The more questions I asked about Hazel, the more stories I heard, and the more I grew to like her. One night my husband and I took his parents out for dinner and, after a bottle of wine, I finally got up the nerve to ask my father-in-law about Hazel. I’m so glad that I did! He told me that when he was about ten or eleven, his family lived with Hazel and her husband in San Francisco a while after they moved from Rhode Island to California. Hazel was definitely a force to be reckoned with, my father-in-law said, quirky, opinionated, outspoken, and sometimes downright mean.

Hazel was from the generation that believed children should be seen and not heard. While she had little tolerance for childhood nonsense, her cats were a different story. She had two cats that she spoiled above all else, but she trained them both to use the toilet. My father-in-law has vivid memories of having to wait for the cats to finish before he could use the bathroom. Her cats meant the world to her and she took them everywhere with her. She even kept a litter box in her car!

I also learned that Hazel and her husband had an old Galaxy 500 with a police interceptor motor. They both worked on the trollies, and she would yell at him to hurry up whenever they were running late. He would drive that car 60 miles an hour while she yelled at him to go faster.

I am glad that I had the nerve to ask about her, and that her family was forthcoming. Now when her name comes up, the way that she died will no longer be the first thing that I think of. The way that she lived will be.

(Rebecca Burrell and members of the family of Hazel Dashiell would love to hear more stories. Mrs. Burrell can be reached at rburrell5@yahoo.com.)