My fingers seem to trip over themselves as I leaf through the paper artifacts in the aging file folder, searching among the letters, clippings, and program notes for the prize, the keys perhaps to my latest burning question. Have I lost them? Really? Well, after all, it’s been 46 years…

Wait! Here they are…Yes…

I pull them out, the two missives. One is a tourist postcard: the picture on the front is of a remarkably ugly Travelodge in Chico, California; above the address (duly postmarked) is a fake “Alfred E. Neuman 4 President” stamp that came with an issue of Mad Magazine.

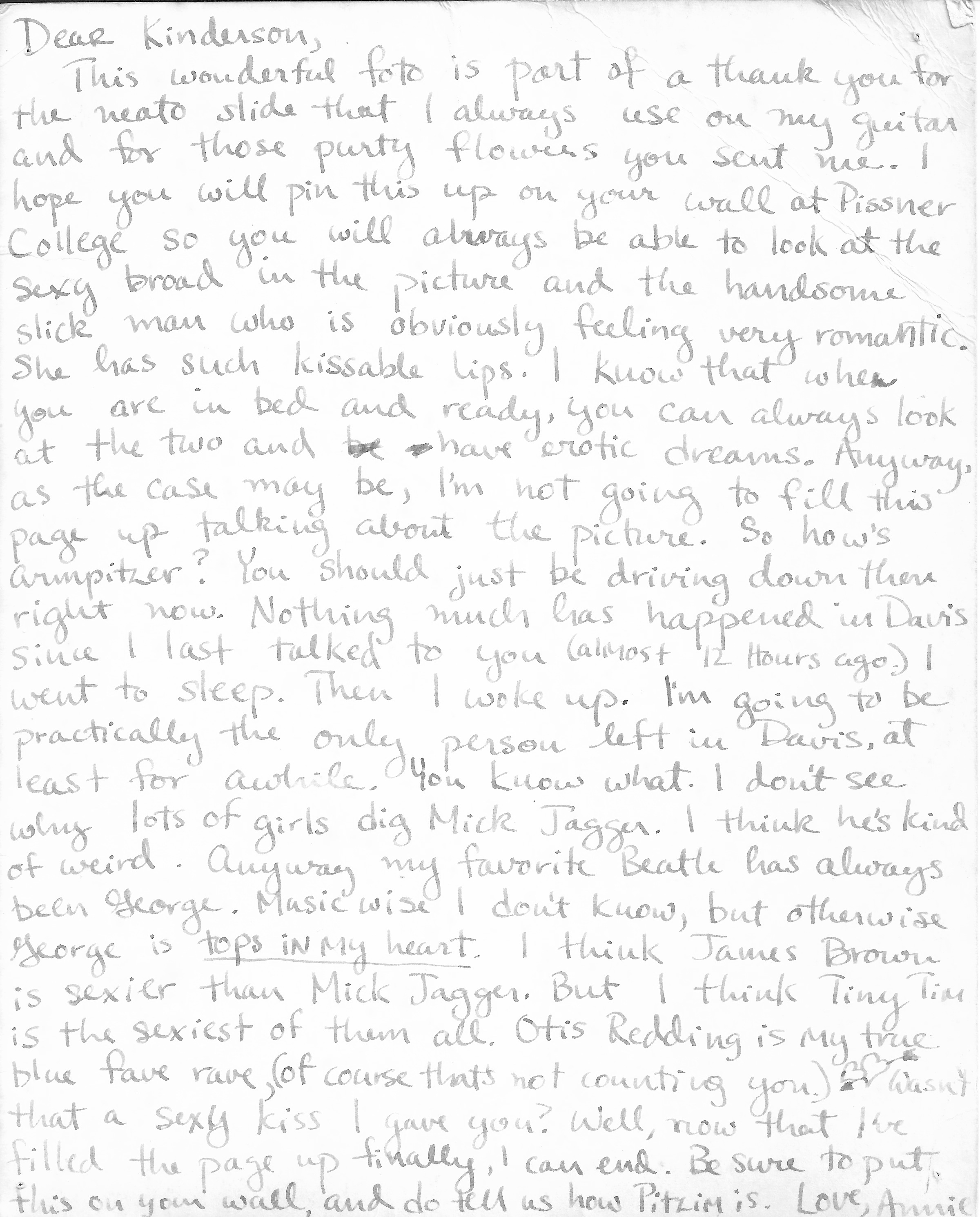

The other is an 8”x10” black-and-white glossy of two gorgeous actors in a silent era film, in fabulously formal attire, sitting in a restaurant. He is leaning in, his face slightly touching her golden locks, and whispering something that can only be intimate, if not indecent. She, gazing out past the audience while pensively fingering her pearl necklace, seems to be wondering, “What does it mean? What should I do?”

The other is an 8”x10” black-and-white glossy of two gorgeous actors in a silent era film, in fabulously formal attire, sitting in a restaurant. He is leaning in, his face slightly touching her golden locks, and whispering something that can only be intimate, if not indecent. She, gazing out past the audience while pensively fingering her pearl necklace, seems to be wondering, “What does it mean? What should I do?”

On the back of these two cards are the only pieces of writing I still have from my high school friend, Annie, addressed directly to me. I haven’t read them in years. As I hold the paper that she once held, and read the words that her once living hand had formed, a troubling thought begins to announce itself, like the loose shutter of an attic window banging in the wind.

* * * * *

It is now 2018. It is 40 years since more than 900 people, including Annie Moore, met their deaths in the Guyanese jungle community called Jonestown. Time has revealed many layers of the mystery surrounding this dumbfounding act of violence, and its impact upon my psyche. But, as I keep discovering, the heart of the onion keeps hiding beneath the layers that still encase it. And what time has not done is heal my wounds. Grief over this event still rings the doorbell regularly. I’ve learned to just go ahead and answer the door. Grief, in this case, has turned out to be the messenger of love.

In my junior year of high school, I left the only town I had known and moved to Davis in Northern California. I was happily surprised at how welcome I felt in this new place, and quickly made what felt like a lot of friends, through many different connections. Besides classmates, friendships came from numerous outside interests, such as sports, politics, and music. And, to my delight, I met a girl, Nancy. In a short while, we became constant companions, and our romance, which lasted for years past high school, felt easy-going and secure, so much so, that it did not even occur to me to avoid friendships with other girls. While there were a couple of brief excursions into romance, most of these girls I considered to be buddies. That was how I felt about Annie.

I don’t remember exactly how or when we met, but it was later into that school year. Annie was artistic. She expressed political views that resonated with mine. She seemed disinterested in what many high school kids were obsessed with, popularity and fashion, and, perhaps most importantly, she loved music. She played guitar, like me, and she was already devoted to the traditional music – folk and blues, particularly – that was drawing me in. I felt an instant kinship with her. Although we had numerous common friends in places such as Christian youth groups, our bond grew outside of those links. Our parents were politically affiliated, and we each became known in each other’s homes. We played music and worked as camp counselors together. Though the actual amount of time we spent together was brief, by the end of high school, Annie had earned her place in my esteem as one of the “special” ones, whose company I enjoyed, and whom I admired. As graduation loomed, and I anticipated the mass exodus I would join (mostly to colleges), it did not occur to me to mourn this friendship, because I had a feeling – a certainty – that we would be lifelong buddies, that we would reconvene our friendship “somewhere out there.”

I had some idea of career pursuits that Annie was considering, and remember a vague notion of plans for moving to Washington, D.C., that I assumed she would follow as I set out for Southern California to attend college. We wrote briefly – I got the two cards above, and another that I’ve lost. It, too, had a Mad Magazine stamp that met with USPS approval: Mona Lisa in her Maidenform Bra. (Did I mention Annie’s sense of humor?) It was I, the inconstant correspondent, who usually took a while to answer back, and some time must have passed before I realized: Annie had stopped writing to me.

I no longer have a firm memory of when I learned about Annie joining Peoples Temple, but bits of news rolled in over time, including the revelation that, as a part of her membership, Annie had cut off communication with most of her old friends, especially the male ones. I had reason to believe this collective, especially its leader Jim Jones, was a little off-kilter. But my faith in Annie’s inner compass was so strong, I felt certain it was just a matter of time until she re-emerged, maybe a little sheepishly, with stories about “my crazy time in that Christian cult.”

It was the rigidity of that faith that made the noise so loud when it cracked and shattered that November day. It took a while for the news to reach me that Annie had not, as I assumed, grabbed all the children in Jonestown and run off into the woods to try and save them. Not only had she died, but her participation in the mass suicide/killing began to look more and more willing.

So began grief’s visits upon my soul. I was young, just beginning to raise a family, and I played my resiliency card as much as I could. After the initial shock, I tried to carry on and make the most of life, despite the awful knowledge within me, and in many ways I succeeded. Life was hard work, and my nose was pressed firmly against the grindstone. The enigma of Annie receded to a speck in my consciousness most of the time. It wasn’t until years later that another tragedy, the murder of a young family friend, tore the bandages off to reveal the festering wound of my grief for Annie.

As I acknowledged the grip of PTSD for the first time, and turned my eyes in earnest upon my pain, I began a (guided) tour of my feelings for my lost friend. It was then that I finally listened to the declaration that grief was trying to deliver: I really loved Annie, so much more than I realized. Grief didn’t care what Annie had done, despite my horror. Grief brushed aside the fact that I could not understand what had happened to her mind. Grief did not even flinch at the shame I felt – shame, as if loving her was a betrayal of my own morals – nor at my insurmountable state of confusion. And the fear – that letting myself feel this love would let misery consume me – was no match for grief’s patience. It simply repeated, like a blues chorus, the same line: “Your heart is broken because you love her.”

* * * *

But what did I love about her? What? As I parted for college at the end of summer in 1972, she was certainly not my most important friend. Nor the closest. Though not by many or much, she was outshined in both categories. Highest on both lists was Nancy, my sweetheart, who was headed north to Washington for college. There were other “best friends” as well, both male and female, from the towns I had lived in. Looking back, though, I recall that Annie seemed to be moving up the ranks, and as summer was drawing to a close, I felt my heart demanding that I acknowledge my affection for her a little more. There was only a short time left, and we agreed (I think at my suggestion) to meet somewhere and just “hang out,” for the first time really, with no particular purpose except talk. As I recall, this took some careful planning because both of us were busily preparing to depart.

Then the unthinkable happened. In a classic display of my disorganized mind, I completely forgot our date until the time had passed. I was mortified! When I realized, I called her house, but her mom, Barbara, told me she had gone off to do other things. Now what? I could not think of anything less pedestrian than flowers, so I went to a florist and bought a pretty bouquet, and wrote out a card eating the most crow I could summon, and took it to her house. She was still out, so I left it with Barbara to give to her. My memory is hazy of what happened next, but apparently we talked the night before I left for Claremont. It was one of my last conversations with anybody before leaving, and the very last one of my life with Annie.

* * * *

“Jonestown” has, for me, come to designate not the place so much as the event of the mass death that occurred there on November 18, 1978. I suppose this is because, like “Pearl Harbor” or “Wounded Knee,” it was the event that brought the place into my consciousness. But this subtle distinction indicates another, more pertinent one: I am an outsider. Not to diminish my membership in another very select group – Those Who Knew Someone Who Died At Jonestown – but my cluelessness about Annie’s life among Peoples Temple was no accident. In testimony to her swift transformation into “follower,” Annie, under Jones’ directive, almost immediately renounced most of her friendships (including with me). And toward the dwindling number of friends she still granted contact, she began to exhibit disdain. In her final message – the suicide note found near her body – the simple division upon which she had come to view the world is captured in its last sentence: “We died because you wouldn’t let us live.” “We”… “You.” We, the faithful Temple members who died. And You, everybody else: skeptics, sheep, oppressors… outsiders… the enemy. I had become a member of You.

* * * *

I thought I was done. Done wrestling with myself about Annie Moore. Done agonizing over unanswerable questions, done being bushwhacked by facts and emotions waiting to be unearthed. “I have swept the minefield,” I thought. Done…

Dream on.

Not long ago, Buck Butler, an old friend from Davis High School, reconnected with me. Out of my view, he had also been profoundly affected by Annie’s death, and we began to share a little of our thoughts and experiences. Most recently, Buck had been preparing his own submission to the jonestown report, and, for the first time ever, we had a long, deep discussion about many things from those school days. In comparing notes about the events leading up to Jonestown, we uncovered some disparities between my version and his. Among other things, Buck pointed me to a new documentary, Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre. for its coverage of some things I had not yet heard. So I watched it.

The documentary raised this question: “Did the four women of the Inner Circle [of which Annie was one] share, with Jim Jones, an equal (or even greater) responsibility for the deaths that day?” That raises an even bigger question: “Had these women not been there, would the deaths have happened at all?” While I was aware of most of the documentary’s revelations, there were here and there pieces of information that chipped away at my memory’s integrity. Perhaps the most inarguable evidence supporting the filmmaker’s suspicions – a memo (discovered after the deaths) from Annie to Jim Jones, not only committing to support the concept of “revolutionary suicide” but also proactively planning its undertaking – was old news. For me, the most profound moment of the film struck during a description – pieced together from interviews of people, including Annie’s own sister, Becky – of Annie’s last hours. To their words, I added my own recollection, and this picture unfurled before me: All the sounds of Temple members succumbing to the poison had stopped. In the silence, only two conscious people remained: Jim Jones, in his deck chair, and Annie Moore. Then, a shot rang out: Jim Jones was now dead, too… For the next hours, Annie existed in the midst of carnage, aware that she was the only person alive in Jonestown. Hours. At some point, finally, she found herself in the cabin she had shared with Jim and two other women, and composed a 4-page note…

Time stopped as my heart unscrambled this information. After that shot, Annie was alone. Truly alone. For the first time in six years, Jim Jones was not materially present in her life. He was just a memory. She had a life changing decision to make. For once, it would not be reflected in the welfare of her community, nor in the eyes of her leader. Suddenly, I heard a voice shouting from my subconscious. “Run!” it urged. “Get help!” The voice, I realized later, was hope. Under a bed somewhere, this hope of mine had been hiding; and, watching this scene with me, it jumped out, revealing itself. Even now, 40 years after her death, I still harbored the hope that “old” Annie – Light Annie, I call her– was still lurking somewhere, waiting for this moment to materialize, overcome Dark Annie, and somehow redeem herself: row her boat to Bodega Bay; call a cab; pound on my door; and throw herself into my arms, sobbing and screaming in bewilderment, “What have I done? What have I done?!!”

But then the sound changed, and I recognized the clickity-clack of the projector, still running the movie I had been watching in my head. As I turned to face the screen of reality, I saw Dark Annie, looking straight into my eyes, silent, and yet somehow speaking directly to my mind: “I already killed her. Years ago. You just wouldn’t believe me. I’ve got to do this. I’ve got to make you see, Ken. It’s the only way.”

…Then she picked up the pistol, pointed it at her head, and pulled the trigger…

It was in that moment, just weeks ago, not 40 years, that my hope for Annie finally died. I could not stop the movie. I could not avert my eyes as Becky’s voice provided the soundtrack for the scene playing in my imagination. Annie shakes hands with the pistol, they nod their mutual pact as she raises it to position, and she squeezes her commitment… the bullet, set into motion like Annie herself, rushes out, unable to turn back from its final task of destruction. I was there, right there in the room, watching the slow-motion journey of the imaginary bullet through her imaginary skull and imaginary brain. The body that crumpled to the imaginary floor, though, was not Annie. It was my hope, killed by that bullet. Dead, lifeless hope.

* * * *

Hope lingers out there, often without our knowledge. Like all emotions, it chooses its own entrances and exits, although it appears to respond to encouragement. It is often painted in a good light, but, like all emotions, it is actually neither good nor evil. It is a tradesperson, in the service of our minds and bodies, survival and comfort. There are times when it pushes us to do what we need to overcome hardship. But it can also play to rather questionable intent: “I hope you die a miserable death!” is, I’m sorry to admit, a sentiment I have felt, if not uttered.

But often, in my life, hope is a side effect of love. When I care about people, particularly the “special” ones, I often develop hopes for them. This is the same hope that seems sort of automatic for many parents with their kids: you picture some life, the best you can imagine for their particular personalities/gifts, and invest yourself in it without even realizing. Part of the dance of separation when they grow up is releasing them from your hopes into the custody of their own.

In Annie’s case, I saw something unique about her, and that vision became a projection into the future. I expected her to do something great in the world, become noteworthy. Nothing more concrete than that. But isn’t that what all hope is? A vision of the unknown future we wish will come to pass? My vision for Annie persisted even after she joined the weird religious group, I had so much faith in her. Perhaps this hope blinded me in some way.

* * * *

When we find ourselves face to face with Misfortune – that is, when some hope that we held has been thwarted by circumstances not in our control – we easily find ourselves pacing the Hall of Justice, either the virtual one in our mind, or the one in the material world. The primary question addressed by the court is “Who gets the blame?” This is the realm of justice. Why blame? Generally, it seems, to facilitate a remedy, usually one or all of these: 1) Reparation: Force the guilty party to return the stolen item or restore it to its original condition; 2) Rehabilitation: Remove the threat of future violations by changing the guilty person, in a way that ensures they won’t repeat that behavior; 3) Punishment. Sometimes the aim of punishment is to rehabilitate through threat, like when you spank a dog; or, by way of example, to deter other potential criminals from committing similar infractions; but perhaps its most common purpose, especially in our hearts, is to appease some “sense of justice” in the minds of the victims – the sense that there is some “price” that, if paid, will ease the suffering they are experiencing.

After watching Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre, I found myself in The Hall. Join me now in the courtroom…

BAILIFF (me): For the case of The World v. Ann Elizabeth Moore, court is now in session. All rise for the Honorable Ken Risling!

JUDGE (me): Be seated. Bailiff, read the charges against Ms. Moore.

BAILIFF (me): Culpability in the deaths of over 900 people, including herself.

JUDGE (me): Prosecutor, you may call the first witness.

PROSECUTOR (me): I call to the stand Witness A, Ken Risling!… Mr. Risling, did you witness anything to suggest Ms. Moore’s complicity in these crimes?

WITNESS A (me): I’ve seen notes she wrote. In one she defends the wisdom of her leader, Jim Jones. In another, she calmly considers different ways to organize and facilitate “revolutionary suicide.” There are numerous books, websites, and movies with copies of these documents. There are also accounts that suggest Annie, as the head nurse, concocted and prepared the poison and trained others to administer it. And forensic investigations leave little doubt that it was she who took the life of my friend, Annie Moore.

PROSECUTOR (me): So, would this suggest to you her complicity in the events of November 18, 1978?

WITNESS A (me): Well, yes. At any step of the way that day, she could have sabotaged the proceedings, poured out the poison, substituted ingredients, or simply raised her voice in protest. And before that, she could have withdrawn her participation, run away, refused to train others, any of those kinds of things. But she didn’t. She stayed until the end, overseeing and making sure it all happened. She stayed.

PROSECUTOR (me): Which leads me to the next charge: Did you witness anything, anything at all, that would absolutely refute the theory that Ms. Moore, along with the other members of “The Inner Circle,” actually conspired to overrule the authority of Jim Jones and take control of the Peoples Temple community, imposing their own vision of what should transpire.

WITNESS A (me): Only that last part, “impose their own vision.” The suicide note makes clear that Annie believed she was following Jones’ vision to the very end, including her final act of suicide.

PROSECUTOR (me): Still, can the record show that you find Ann Moore wholly or in part to blame for the deaths that day?

WITNESS A (me): Yes.

PROSECUTOR (me): The prosecution rests.

JUDGE (me): Defense! Your witness.

DEFENSE ATTORNEY (me): Mr. Risling, I hear that you find Ms. Moore culpable in the deaths in Jonestown. And I am not asking you to refute that testimony. But I would like to reframe the notion of “blame” by asking a slightly different question, twice. First, do you believe that, if your friend Ms. Moore – Annie – had not been there that day, the deaths would have been prevented?

WITNESS A (me): Well, that’s hard to speculate. I mean, she was responsible for a lot of the organizing. It was an incredibly well orchestrated event, almost unbelievable that it didn’t turn chaotic. I believe Annie’s devotion to its planning helped make that possible, so her absence might have tipped the scales to where more people fled. And, from the voice I hear in their communications, Annie seemed to have the ear of Jones. I think he trusted her. If Annie hadn’t been there, supporting the idea of “revolutionary suicide,” an entirely different course of action might have been chosen. I don’t know.

DEFENSE ATTORNEY (me): You don’t really know. It’s conditional, is that right?

WITNESS A (me): Yes. If Annie had never joined Peoples Temple, someone else might have been there in her place. It seems that even her choice to become a nurse was influenced by Jones. I can imagine someone else filling Annie’s shoes at Jonestown. So, yeah. It depends.

DEFENSE ATTORNEY (me): I see. Let’s now ask the same question about someone else: If Jim Jones had not been there, would these deaths have occurred in Jonestown that day?

WITNESS A (me): Are you kidding? Of course not.

DEFENSE ATTORNEY (me): So would it be correct to say that you place primary blame on Jim Jones? Still?

WITNESS A (me): Yes.

DEFENSE ATTORNEY (me): Your honor, I rest my case.

JUDGE (me): Counselors: please approach the bench.

[They approach.]

JUDGE (me): Prosecutor, do you have personal feelings regarding the defendant and the outcome of this trial? Please state them now.

PROSECUTOR (me): Yes, your honor. She killed my good friend, Annie Moore. I will never stop mourning. She made me question everything I understood about knowing a person’s heart, and being good. And she made me ashamed. I will never forgive her.

JUDGE (me): Defense, I direct the same question to you.

DEFENSE ATTORNEY (me): Your honor, I loved the defendant Annie Moore with all my heart. I cannot stop doubting that every stitch of the person I knew so well was completely wiped out. But I also believe that, if it was, it was at the hands of someone else. And that is a person that I have to hate.

[After a recess, the court is called to order and the judge returns.]

JUDGE (me): This court is convened to serve the interests of justice. Until a verdict is handed down, no one party’s standing, situation, pain, or gain, may be considered, only the facts pertaining to the charges. Justice demands that I conclude a trial with one of two outcomes: a verdict of innocence, upon which I free the defendant; or a guilty verdict, and an appropriate sentence. Without both of those possibilities, the purpose of these proceedings cannot be fulfilled. On the question of guilt, there is not a simple yes or no regarding the defendant’s singular culpability. At my most generous, I would find her enormously gullible. Even then, though, she is clearly more guilty than anyone alive in this room today. But that is only half of my job. In keeping with the intent of justice, a guilty defendant must be sentenced to a punishment appropriate to the crime. Is there reparation possible? The victims are all dead, so, no I’m afraid that is irreversible. What about rehabilitation? The defendant, dead also, cannot be rehabilitated. And, as for punishment, which at best might assuage some pain experienced by the victims’ survivors, the most severe punishment allowable, death, has already been served by the defendant. The “price” has already been paid. Any further sentence would rightfully be deemed “double jeopardy,” and cannot be imposed. Therefore, it is the opinion of the court that this case serves no purpose of justice, and is dismissed.

[The gavel is struck. Fade to black.]

* * * *

There. I should be relieved now. Right? The question of blame has been put into perspective, if not to rest.

Ah, but only for one defendant. There is another one, it turns out, who is still hiding among the living.

* * * *

Josef Mengele, one of the doctors who personified the evil at work at the death camps of Auschwitz during the Nazi occupation of Poland in the 1940s, earned the nickname “Angel of Death” for his heinous medical experiments on prisoners. As I pondered the events at Jonestown and Annie’s role in them once again, I suddenly remembered his name, and against my will, compared Annie to him. Not that she was ever as awful as Mengele: fueled by his racist ideology, he was utterly cruel to his victims. He had no hope for their future ever, his experiments were designed for the benefit of others, and his intent at the beginning of any experiment was to kill the subjects in order to facilitate an autopsy. Annie, on the contrary, loved the people of Jonestown, and even in planning their deaths, sought the least painful and stressful means.

No, what connects the two for me is that they were both medical professionals who were also believers – she in Jones, he in Hitler – so fanatical, that they were willing to abandon their training, their sworn goal, perhaps even their instinct, to protect life. Instead, they chose to expedite death. The twisted logic that created the “Final Solution” and “Revolutionary Suicide” did not originate with them, but both were instrumental in implementing the vision of their Führers. For Annie’s part, she was willing to facilitate the deaths not only of those desiring it, but also those less committed to it, who needed coercion, and worst of all, helped dispatch the utterly unwilling: infants who were injected with or force-fed poison. Hitler had Mengele. Annie, it dawned on me, was Jim Jones’ Angel of Death. Dawn was never so dark.

* * * *

My conversation with Buck raised a number of questions, seemingly inconsequential, but still intriguing partly because, after so long, I still did not know the answers with certainty. One was the date when Annie moved to Redwood Valley and joined Peoples Temple. In my memory, it was always toward the end of my first year in college. “Huh,” Buck said, “I was under the impression it was immediately at the end of summer after we graduated high school.” That didn’t sound right, but I couldn’t place the reason. Yet, when I watched the documentary, Becky Moore corroborated Buck’s take on it: Annie, at the end of summer after graduation, cancelled her plans to live with Becky in Washington D.C., having decided instead to join her older sister Carolyn, already a member for six years. And the girls’ father John Moore recalled that shortly after the family relocated to Berkeley that September, Annie moved to Redwood Valley. In no time, Annie had cut off her long hair and planned to sell all her possessions, including her guitar.

Another question was about her sexuality. Annie was one of four women profiled on the documentary, and three of them – Jim’s wife, Marceline; Maria Katsaris; and Annie’s sister Carolyn – had shared a bed with Jones. But what about Annie and Jones? Were they also lovers? One of those riddles that might not be solvable any more, but nonetheless inspired me to ponder and prod my memory.

There was a play about Jonestown put on in Berkeley awhile back. I remembered, the actor who played Annie found indications in Annie’s writings that she considered herself lesbian. But I fell short of endorsing that idea.

I also remembered a conversation with Eileen, who I saw as one of Annie’s best friends. Eileen was the last person I was aware of among my friends who Annie allowed herself contact with. At some point, while we were still in college – and long before Annie had moved to Guyana – Eileen recounted a conversation she’d had with her, which went something like this:

Annie told me that Jim claims “All men are homosexual.” Except for him, of course. I said, “And you believe that?!” And she says, “Seems like it might be true…” So I asked her, “You mean, you think Jon Andrews and Ken Risling are homosexual?” And you know what she said? “Well, not them!”

We both laughed. I thought Jones sounded crazy, and was alarmed at Annie’s gullibility, but was also charmed by the surprising thought of Jon and me as the “benchmarks of heterosexuality.” I did not think of Annie as someone who even checked in on my sexuality. True, we had, like kids at camp, shared tales of first kisses and things like that, but it felt like buddy talk. I didn’t dwell for long on Eileen’s story.

This time around, though, a little light started blinking in the corner of my mind’s eye. There were those cards Annie sent me at the beginning of college, three of them… Yeah, it seems like there was a subtler, underlying message, sort a joke – she always joked, she was Coyote – but one rather uncharacteristic of Annie, almost a flirtation. I don’t think I took it too seriously. But now it seemed to glare with potential meaning.

I went searching for the cards, now treasured relics, in a filing cabinet. When I found the folder where I kept them squirreled away, I felt a lump in my throat. One of them – Mona-Lisa-In-A-Bra – was missing. Of the two I had, the Chico Travelodge postcard just seemed typical of Annie’s irreverent humor. It was sent in July, before I left for college. That’s right, the family trip back east… When I pulled out the 8×10 glossy, I knew I’d found the one I was looking for. I glanced at the picture, then flipped it over and began to read, until… There. There it is. Oh, my God! She was flirting! She was! How did I miss it?… And why do I feel so… bad?

* * * *

She wrote the card as I was being driven to my new college down south. We had just talked “almost 12 hours ago.” Twelve hours. I knew that feeling. I woke up thinking about you. I wish you were still here so we could talk some more. I couldn’t wait any longer to write to you. She thanked me for the guitar slide I had given her, and “the purty flowers,” my apology bouquet. Then she turns to the picture on the front, and gets, well, suggestive, finally saying, “I know that when you are in bed and ready, you can always look at the two and have erotic dreams.”

Back then, on my own for the first time as an adult, in my new school and all butterflies, I imagine I was just delighted to have something from someone so familiar, and tried not to read too much into its message. “She’s joking! I love her sense of humor!” It’s true, it was peppered with classic examples of her humor, like deliberate misspellings (including of my name). But I also know I was already feeling the pangs of missing my girlfriend, Nancy. I think I did not want the complications that Annie’s feelings – now so glaring – demanded I deal with. Annie was a treasured friend, to whom I felt almost uniquely connected. I did not want to have to say, “I don’t think of you that way,” or more truthfully, “I love you, but I feel more romantically toward Nancy than you.” I only wanted to convey the joy her card had given me, to say, “Thank goodness we’re friends! This letter is so goofy, so familiar, so you. You are so dear to me.” I did not want to start my new, scary school year by jilting one of my best friends. Instead – I think – I closed my eyes and imagined away the conflict.

This time they’re open. After a brief detour into newsy-ness, the letter’s theme abruptly turns to which male music icon Annie finds most attractive. This may have been a more expected topic for us. But not this sentence, “Otis Redding is my true-blue fave rave (of course that’s not counting you.)”… followed by two tiny hearts pierced by an arrow, and “Wasn’t that a sexy kiss I gave you?” Okay, now it is just obvious. Her words are joking, but her heart is not. And these other words, from the lost card, are also circling around in my memory: “Leave Nancy and run away with me! (Ha, ha, just joking!)” But this didn’t really seem like joking either.

Now it comes back: I blew it off. Shined it on. I adored Annie, and didn’t know how to process this disturbance rippling across the still pond of our friendship. So I did the “guy” thing with all the insensitivity I could muster: I didn’t say anything at all about it. I sent her letters filled with words and one Big, Glaring Omission.

Had this realization dawned on me about anyone else, I think that I would have simply felt sheepish. And maybe a little flattered (“She had a crush on me!”). But as I let the words on these cards sink in, my head began to spin. There was another change occurring at the same time: the chronological backdrop. For 46 years, I had thought that she left for Redwood Valley months after I left for college. I was wrong. It wasn’t months… it was weeks, at most. In fact, our unconsummated “date,” the flowers, the last talks and letters, they had all happened in the time between the day she decided to join Peoples Temple, and the day it actually happened.

And why am I so surprised now?

* * * *

She never mentioned it…

In my memory, Annie and I were close in a lot of ways. I felt like a confidant, at least about certain things. These included the social issues that we were passionate about, but also more personal topics, like music, or relationships… or caring about children. Annie could be reserved, especially in public, but she never seemed secretive. I remember lively conversations in which neither of us was afraid to disagree with the other. In this setting, it is hard to understand that I remember exactly zero mention of her big sister Carolyn, how she’d been living in a Christian commune for six years. It seems like she would have shared at least some of her self-talk while she considered joining Peoples Temple herself. But she didn’t. “Why?” my mind demands. Of all her friends, why was she hiding something so important from me?

A more subtle, but to me even greater impact, was made by Annie’s tone when she spoke and wrote. After exhuming the postcards, and feeling absolutely drenched in new, unanswered questions, I began searching the Internet for a copy of the letter I remembered, sent to Becky and her first husband, announcing Annie’s decision to join Peoples Temple. I wanted that date. I found it, posted by Becky, along with many letters Annie had written them in her first two years or so in Peoples Temple. Sure enough, the date on the letter, August 7, confirmed my surprised realization.

But I had never seen these other letters, windows into Annie’s mind, the Annie whose life I had been cut out of. I read them hungrily. Their content reveals much that I did not know, facts of her life – like, she had a boyfriend there, at least for awhile – but equally important, her attitude and way of thinking and speaking come through. I was relieved to get such a familiar feeling as I read. Still Annie! Her overall voice, in letters written both before and after her decision, had a consistency: sober, determined, sincere, independent; open, but with a hint of judgmental-ness (including, at times, toward herself). Perhaps this was partly the result of an editing choice by Becky. But what really sinks in for me is that the voice in the two flirtatious letters contains absolutely none of that familiar tone. They sound more like an awkward schoolgirl toying with the forbidden fruit, her new-found libido. Cautious and reckless, satirical and suggestive, all at once. And completely out of place in the continuum of her expression, like a traffic signal in the middle of a long, straight freeway. What made this blip happen? My imagination ran away with me.I know Annie saw that joining Peoples Temple was a monumental decision, a huge change in her life. She was not impulsive. I could picture her

…slowly, deliberately climbing the ladder to the high dive of commitment, carefully considering each tread, until she reached the top; and then, heart pounding, peeking over the end of the board to her destination, far down below: the water. Her new life. A moment’s hesitation, perhaps a little dizziness, then she pulls herself to her feet, facing out, and standing there, she realizes: “I’m going to do it.” She visualizes her feet leaving the board, and her body plummeting, faster, faster, as the tiny pool gets larger and larger, closer, and closer, the wind rushing around her ears. “I know now. I can do it!” Just then, something changes. In that exhilarating moment when you realize you are the master of your own fears, sometimes other doors swing open…

[And here is where the enigma of the postcards is explained by my swirling brain:]

As she steps to the edge of the board, a light suddenly illuminates a dark place in her mind that makes her pause. “Ken Risling. I’ve been afraid to admit it to myself, but I’m kinda crazy about him! I’ve been afraid to approach him, afraid to risk the rejection, but why? For fear that I’ll never see him again? But I’m about to choose that fate, anyway, if I join Peoples Temple. I realize I want to follow that feeling, to find out what it means. I know he’s all involved with Nancy and everything, but what if he’s secretly crazy about me too? How am I going to find out? What’s to lose by letting him know? What’s to lose by asking? Nothing, that’s what. How can I believe in my courage if I’m too chicken to level with a boy? I mean, really!” So she climbs down, telling herself she can climb right back up next week, and writes those cards.

Welcome to my imagination. That’s Part 1 of “Trying To Figure Out What Annie Was Thinking.” Part 2, “Choose The Ending”, is the playground of survivor’s guilt.

Ending A (what actually happened): I respond to her cards with zero reaction to her advances. She gets it. “He’s uncomfortable now. We’re not going to happen. Now I know. Now I can leap off that diving board, never see or speak with him again, and feel at peace with it. Glad I asked.”

Ending B: I respond, as I suggested, sincerely expressing ever-so-much-more-than-ordinary feelings. Annie, emboldened, extends her pause. Then…

Sub-endings B1, B2, B3, …, B∞: So many possibilities: we fall madly in love; or we agree to try dating, which doesn’t lead to much, but meanwhile, Annie, with her newly awakened sexual awareness, meets the love of her life; or… etc., etc.

It doesn’t matter which way it gets there, it always ends up that Annie’s pause gives her the perspective to see that she is too much person to bottle up as a Jones follower, and she never joins Peoples Temple. So she lives. And Jones never gets his Angel of Death. So on November 19, 1978, all those people are still alive, too.

Ending C: Not important. My “If Only…” demon only cares about Ending B.

Ending B. That’s where I end up, in my imagination. Over and over. I navigate detours to other possibilities, but, like a character in a Rod Serling screenplay, I somehow always find myself standing right before Ending B. If only I had seen the traffic signal on the freeway; if only I had acknowledged that she was making her heart vulnerable in those cards, and had found my vulnerability to offer back; if only I had known the decision she was contemplating that fateful summer… etc., etc., etc.: then maybe Annie would still be alive… and all those other people…

Survivor’s guilt knows no mercy.

* * * *

There will always be pain in my journey, I know that. This excursion was a tough one. I have named my beloved Annie Moore ”Jonestown’s Angel Of Death”, and accused her of killing my hope. Which she did. Perhaps worst of all is the awful, lingering suspicion of the possibility that for a moment, completely unbeknownst to me, I held in my hand the long-sought power to reverse Annie’s fate – the shears to clip her terrible Angel’s wings – and save not only her life, but the lives of hundreds of others. But in my innocence, I simply let go… I let go… I let go… And she flew away.

* * * *

I know that my anguish and remorse are completely unfounded. I am innocent beyond all doubt. And it is unlikely, in reality, that anything I could have done would have changed her mind. She was a very determined, independent person. But I am a survivor, someone who has lost loved ones, faith, and hope at the hands of suicide, murder, and betrayal. Torturing ourselves is what we do. I would never do this to myself, if I had the choice. But I don’t think I do. I will probably remain the other defendant in this case for the rest of my life.

What I can choose is to carry on with my eyes open. It has not all been painful. I also discovered things that lifted my heart – more evidence of Good Annie, Light Annie, and this delivered by her own voice, in letters, even after she had joined Peoples Temple. Something I thought I would never find.

Annie did not kill all my hope. Some hope really needed to die: the hope that she would somehow spring back to life and make done deeds undone again. That is nothing useful to cling to.

But there is other hope, including this one: I hope that Annie’s story will not fade into obscurity. It is the story of how a person so good, true, and kind, could be wrested away from her own goodness by the manipulations of another. I hope, instead, it becomes a warning light in people’s minds, people who are in the right places at the right times to prevent such a terrible thing from happening again.

(Ken Risling is a writer and musician. He lives in Northern California. His previous articles are here. He may be reached at rise@sonic.net.)